Business Resiliency Requires Banning Stock Buybacks

March 19, 2020

By Lenore Palladino

As millions face unemployment and dire financial prospects amid the coronavirus pandemic, hotels, airlines, and other large corporations are repeating the script of 2008: asking for massive public bailouts after years of extractive shareholder payments. Before the government buoys these companies with the public’s money, we must ensure that they are resilient in the future by examining and forbidding some of their most societally harmful practices. The explosion of stock buybacks in recent years deserves particular attention.

Stock buybacks describe the repurchase by corporations of their own shares on the open market, a practice that raises stock prices for anyone who sells shares while the stock price is elevated. They’ve long been called out by economists like William Lazonick as incentivizing “profits without prosperity,” but this new crisis is bringing fresh scrutiny to the waste of corporate funds on buybacks. They’ve been virtually unregulated for decades, allowing corporate executives to juice stock prices without improving the actual productivity of their companies.

While buybacks might sound innocent in theory, it’s an open secret on Wall Street that those “in the know” about a company’s buyback activity can make plenty of money for themselves before the rest of the market adjusts. My recent research shows that the practice of corporate insiders selling meaningful amounts of their own stock is nearly twice as common in quarters when stock buybacks are also occurring than in non-buyback quarters. In effect, it’s legal insider trading.

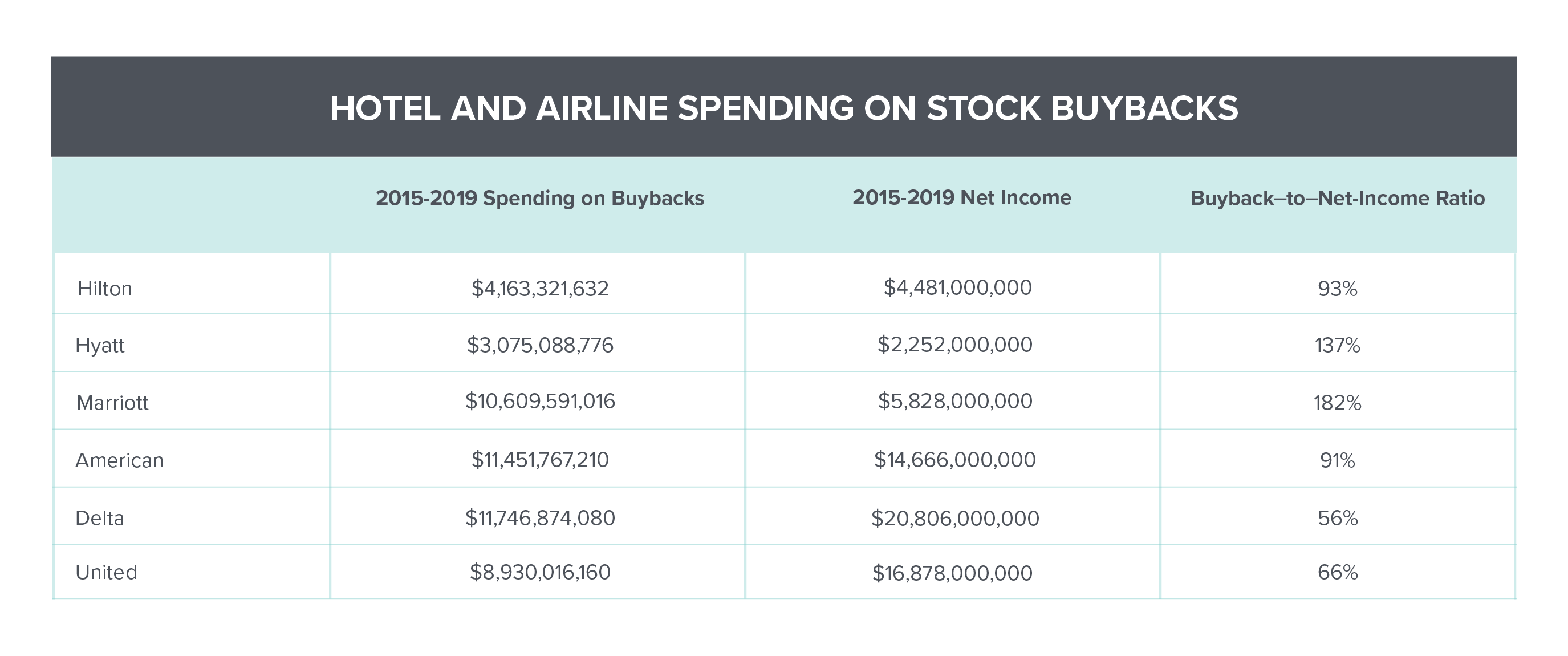

Today, hotels are asking for $250 billion in a federal bailout, while airlines are asking for $50 billion. Both industries have spent massive amounts on stock buybacks over the last 10 years. Below is a chart of spending by some of the largest hotels and airlines on stock buybacks, showing that companies like Marriott have spent $10.6 billion on stock buybacks over the last five years, with $2.3 billion in 2019 alone. American Airlines and Delta each spent over $11 billion in the last five years, while United spent $9 billion. (That’s not to mention the pileup in corporate debt by many of these companies.) The chart shows the percentage of a company’s net income that was spent on stock buybacks—funds that could have been productively invested in ensuring businesses’ resiliency in the face of a downturn.

While among the hotels and their suppliers are many small businesses, it is large chains that have spent big on buybacks. Those payouts could have sustained employees through this crisis in the form of paid sick, medical, and family leave.

Given this history, any bailout of the private sector—that’s the public’s money spent to maintain these companies in this time of stress—must be conditional on an end to the practice of stock buybacks (a condition President Trump says he is “okay with”), along with worker representation on corporate boards going forward, and broader requirements that companies keep workers on their payrolls. The coronavirus crisis cannot end up as a giveaway to wealthy shareholders, but must instead be a reckoning with the underlying harms of shareholder primacy and a turn toward a more resilient economy.