What the NEPA Data Actually Shows, and the Case for Progressive Permitting Reform

July 21, 2023

By Rhiana Gunn-Wright, Kristina Karlsson

Earlier this week, a guest post by Aidan Mackenzie and Santi Ruiz on Noah Smith’s blog critiqued our recent research on the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and work authored in partnership with Professor Jamie Pleune, JD, LLM. We have put together a response in collaboration with Professor Pleune.

To start, the authors make the point that her use of United States Forest Service (USFS) data on Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) review times is not representative of the case for renewables. In her Roosevelt brief, Professor Pleune explains that the USFS is the only permitting agency to collect comprehensive data on NEPA reviews at all levels, and that it is the permitting body that issues the most EIS statements. The data represents 41,000 cases from 2004 to 2020. The CEQ survey the authors cite as an alternative reviews only 1,276 cases, and supports the findings of Professor Pleune’s academic report referenced in her Roosevelt brief. In her and her co-author’s own words:

Consistent with the CEQ report, we found that between 2005 and 2020, the average (mean) time to complete an EIS was 3.4 years (1,240 days). In contrast, the median time was 2.8 years (1,006 days). Turning to EAs, the average time to complete was 1.7 years (618 days), while the median time was only 1.2 years (445 days). Finally, looking to CEs, the average time to complete a CE was 7 months (209 days), while the median time was just over half the mean at slightly under 4 months (112 days).

In response to Mackenzie and Ruiz’s blog post, Jamie adds:

More importantly, our study pointed out that at every level of review, there was a big difference between the average (mean) and the median. This indicated that the average was skewed by projects that encountered abnormal delays. It also indicated that the majority of projects were completed more quickly than the commonly cited time frames. The wide variation in completion times for NEPA documents at all levels of review provided two insights. First, efficiency does happen within the existing regulatory structure, which is important when understanding what actually causes delay. Second, abnormal delays were observed at all levels of review, which provided further evidence that the analytical process was not necessarily the source of delay. If it were, you would expect to see clear demarcations at different levels of review. Instead, the data revealed strong overlaps. This provided a strong indication that factors external to NEPA’s analytical process affects timelines. Our research sought to understand that nuance, which is critical to crafting effective reforms. McKenzie and Ruiz focused solely on average time frames in order to argue that NEPA causes delay instead of asking whether it is possible to achieve the goals of NEPA in a more efficient manner. The data suggests that efficiency is possible, and that it occurs. Our research sought to identify ways to implement efficiency, without losing sight of NEPA’s central purpose, which is to avoid unnecessary and avoidable environmental or social harm.

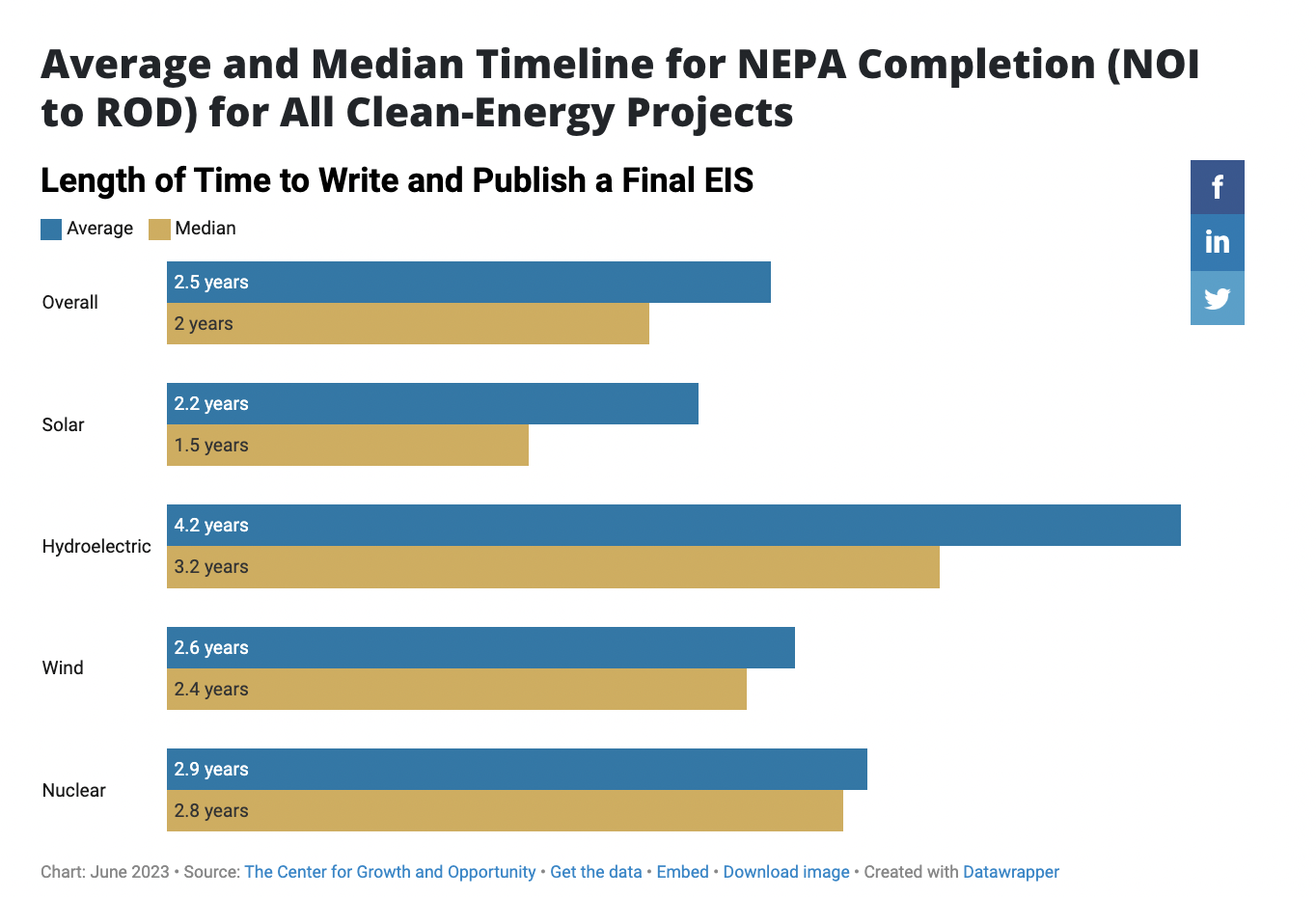

Mckenzie and Ruiz also argue that because USFS is not the most frequent lead permitting agency for renewable projects, the data does not accurately reflect the effect of NEPA on renewable energy development. To support this, they cite data gathered in a report published by the Center for Growth and Opportunity at Utah State University that finds that review times for renewable energy projects are even shorter than the averages found in the USFS study. Average review times for renewables are 2.5 years, with a median of two years. The authors chose not to include this finding in their blog post.

If the motivation for criticizing the use of USFS data was to argue that NEPA reviews will have a larger impact on renewables than the USFS data is able to show, the citations in Mckenzie and Ruiz’s blog post disprove their own point.

The authors’ speculation about the inadequacies of the data related to CEs and the impact of litigation are not new concerns, nor do they undermine the core findings in Professor Pleune’s brief nor her academic article published by Columbia Law. As McKenzie and Ruiz acknowledge:

Data on time to complete CEs is not tracked, and anecdotal evidence varies widely across federal agencies. GAO reported anecdotal evidence that CEs from DOE and DOI usually take 1-2 days while the Forest Service takes 177 days on average. In practice, average times will vary heavily depending on whether agencies track CEs that cover the most trivial actions (e.g. paying staff, etc).

Neither the Roosevelt Institute nor Professor Pleune has argued that NEPA is working ideally in its current state—her brief is not a “full-throated defense of NEPA.” To the contrary, Professor Pleune’s research focuses on identifying workable solutions with demonstrated efficacy that will improve NEPA’s efficiency.

We understand the need to rapidly build out renewable energy at the pace required to counter the crushing pace of climate change and meet decarbonization goals, national and international. And we argue that the US lacks some of the governmental infrastructure—particularly a lack of staff capacity—needed to support this development. However, finding efficiency by eliminating the process for environmental review is not a wise approach. The types of sweeping changes to NEPA that Mckenzie and Ruiz advocate lack firm evidence that they will in fact solve the sources of delay.

Contrary to what their post suggests, it is not only “short-sighted conservationists,” competing companies, or “NIMBYs protecting their property values” who stand to benefit from the review process. NEPA has played a crucial—though still inadequate—role for frontline communities often silenced by deep legacies of environmental and systemic racism, giving them more say in what infrastructure is built in their communities and pushing those in power to better account for the potential harms of projects.

That is why we have proposed reforms that seek to streamline NEPA’s review processes (such as programmatic review, increased agency staffing, greater use of FAST-41) and improved democratic participation.

For example, we agree that the threat of litigation has a real impact on timelines, and there is no doubt that dishonest actors have taken advantage of NEPA to file self-serving suits. But it is important to recognize that litigation, especially for frontline communities, has been used as a last resort precisely because other methods of democratic participation and oversight—including NEPA’s community participation processes—have either been ineffective or inaccessible. Making it harder to file suit will not dissipate the discontent that led to litigation. It will simply mean people look for other channels to express this frustration—including joining forces with astroturfed groups that oppose renewable energy projects and seed disinformation to do so. A sensible, research-based reform to reduce litigation would move community engagement early in the development process, heading off more contentious opposition down the line. Indeed, one of the silver linings of the debt ceiling deal is that community engagement has been moved earlier, to the notice of intent.

The progressive NEPA reforms we are advocating also recognize that no matter how quickly we build, the green transition is going to be accomplished over decades not years. Given that, even the fastest possible timelines require sustained, widespread support, which requires building community trust. Productive community engagement is actually essential to building a lasting transition. At a time with such little trust in government and so much polarization, it is tempting to see curtailing NEPA—especially the aspects related to litigation and public participation—as some type of silver bullet that will deliver the clean energy build-out we need without the messy work of democracy. But the reforms Mckenzie and Ruiz propose are not without consequence.

The clean energy transition is as much a political process as it is a technical one; NEPA reforms that make it easier for those with more power—whether developers, technocrats, or elected officials—to steamroll and dismiss public concerns are likely to undercut support for renewable energy.

That is why we have provided proposals that would make review processes more efficient while helping foster public support for renewable projects and building the lasting political power to keep this transition moving. We simply don’t have time for anything else.

Related Resources

Choosing between Environmental Standards and a Rapid Transition to Renewable Energy Is a False Dilemma

brief Opens in new windowA Justice-Centered Vision for Permitting Reform

blog Opens in new windowAmerica’s Clean Energy Transition Needs Federal Action—Not Rollbacks

blog Opens in new window