What We’re Talking about When We Talk about Governing Power

February 16, 2024

By Jee Kim, Eric A. Paul

The Power Building Initiative (PBI) at the Roosevelt Institute was created in 2020 to support base- and power-building organizations through grantmaking and a learning community gathered to sharpen strategy and practice. Over three years, PBI distributed $5 million in rapid response grantmaking and supported strategy conversations across 13 organizations including Black Voters Matter, Center for Popular Democracy, Color of Change, Community Change, Faith in Action, National Domestic Workers Alliance, People’s Action Institute, PowerSwitch Action, Right to the City, State Power Caucus, and United We Dream.

The PBI community explored topics like depth and breadth in organizing models, narrative change, mutual aid, and governing power—the topic of our final convening, which participants agreed would be beneficial to summarize and share highlights with the broader progressive community. We began with a definition formulated by the Grassroots Power Project familiar to many PBI members: Governing power is “the ability to win and sustain power within multiple arenas of decision-making so as to shift the power structure of governance and establish a new common sense of governing.”

Two recent developments make the relationship between social movements and governing power especially pressing. First, the strength of social movements, including Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, Occupy Wall Street, and campaigns for immigrant rights and climate justice. Many leaders from these movements have worked tirelessly to convert social movement energy into potentially more durable forms of institutional political power. Second, a crop of electeds have both ridden movement momentum and inspired a generation of activists to engage elections with an enthusiasm perhaps not seen since Barack Obama and Jesse Jackson before him. The presidential campaigns of Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, the rise of “the Squad,” and numerous other local victories both reflect and have energized bold inside/outside change strategies. Movements made free college for all and the Green New Deal politically palatable, and historic legislative victories like the Inflation Reduction Act are unimaginable without social movements and their elected champions.

Organizers developed many of these movements and strategies in dialogue with a rich history of progressive thought. The question of governing power was front and center during the civil rights movement, nowhere more explicit than in Bayard Rustin’s From Protest to Politics: The Future of the Civil Rights Movement. Nearly 60 years (!) since its publication, Rustin’s canonical piece and insight that protest movements would need to become political and leverage the power of the state remains more agitation than conventional wisdom. Many contemporary thinkers and organizers have picked up the baton and updated the conversation.

For at least the last decade, the Grassroots Power Project has also been developing theory and practical training materials centered on governing power for organizers. The Equity Research Institute has been documenting the evolution of community organizing into electoral engagement for many years, laying out distinct arenas of contestation for governing power in Change States: A Framework for Progressive Governance. More recently, Paul and Mark Engler have been commenting for a broader progressive audience on co-governance, the relationship/partnership between movements and the candidates they help gain public office. Race Forward’s recent report Co-Governing Toward Multiracial Democracy explores the ways community organizations can engage with local government staff and officials to build out co-governance models and democratic practices.

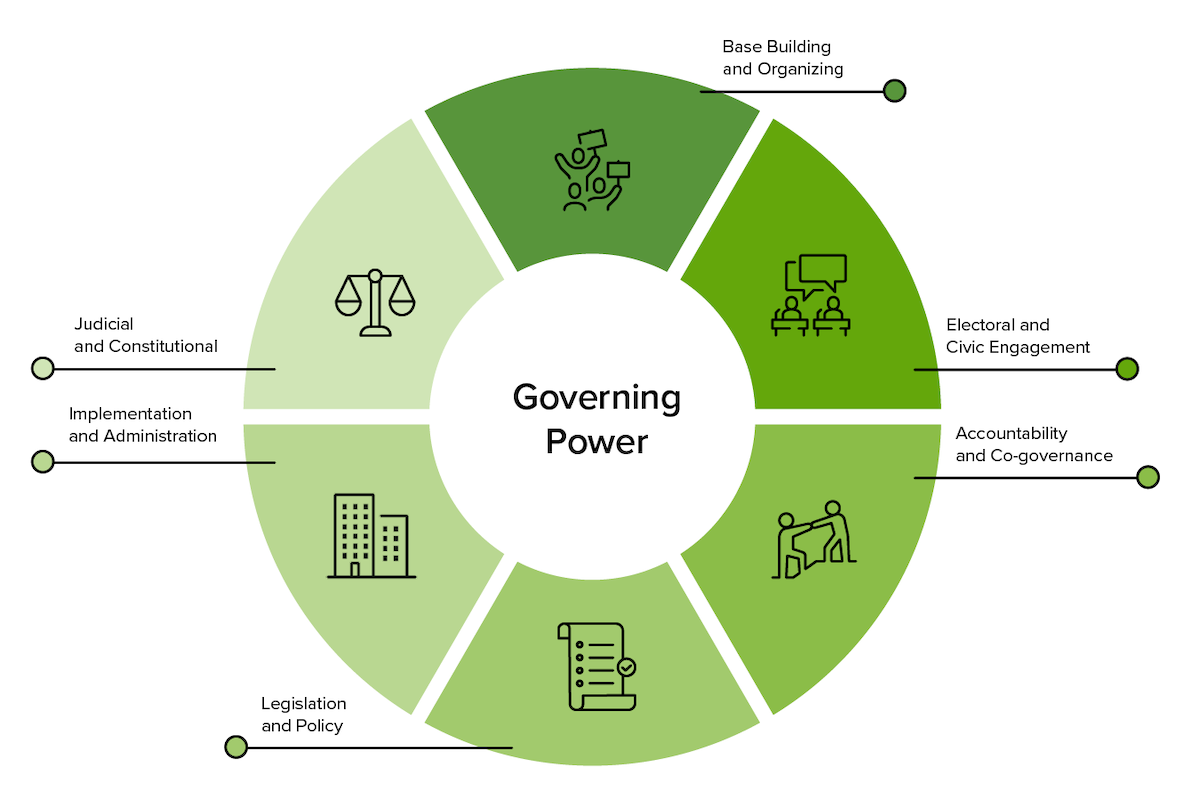

The contemporary dialogue is robust but also reflects a concept of governing power that is broad and means many things to many people. At one end of the spectrum is social movement organizing, pushing from outside and at the edges of formal political channels. Other approaches, like constitutional reform and judiciary composition, require long-term strategies anchored inside of political institutions and systems. In figure 1, we have attempted to synthesize much of the scholarship above into a spectrum of governing power, from outside game (left) to inside game (right).

Figure 1: Spectrum of Governing Power

- Base Building and Organizing: Including everything from more “organic” social movements to advocacy and organizing campaigns with specific, named policy goals, these organizing tactics are mobilized to make progress from the bottom up.

- Electoral and Civic Engagement: The proliferation of integrated voter engagement and deep canvassing reflects an increased commitment to participating in the political system through voting, developing candidates, etc.

- Accountability and Co-governance: A productive relationship between movements and candidates—in which electeds rely on grassroots organizations as a base of strength and support—can in turn require electeds to maintain a degree of accountability.

- Legislation and Policy: Closely related to co-governance, this type of power centers the ability to influence, alter, or set the terms of the debate in formulating policies and/or laws.

- Implementation and Administration: Once priorities are translated into legislation, their implementation and administration is critical. This capacity extends beyond electeds and includes appointeds, agency staff, and civil society organizations.

- Judicial and Constitutional: Adjudicating and setting the rules of the game (of democracy itself) are perhaps the furthest upstream we can go on governing power. Developing legal frameworks and worldview, in addition to talent pipelines to reproduce them, is needed to exercise this profoundly consequential aspect of governing power.

We generated this spectrum to anchor our closing session with the Power Building community. We hoped this shared vocabulary and framework would support the organizing networks’ ability to locate respective efforts and strategize the state of our broader progressive infrastructure. Our dialogue covered three broad areas.

- The what—the components of governing power: There was a recognition that the field has built capacity on electoral engagement, but that there is more work to be done on accountability and co-governance. In addition, executing the middle of the spectrum requires institutional structures—including new and stronger infrastructure focused on developing a pipeline of talent from the base—as a critical part of our long-term strategy.

There was also debate over the conceptualization of a spectrum, which could indicate progression or greater value and impact moving left to right. Instead of a spectrum, should it be a circle (figure 2)? This way, each of the components of the spectrum are needed to attain governing power, in full.

Figure 2: Circle of Governing Power

And when understood in this way, could governing power be replaced with other objectives in the center, like economic or narrative power, that also require a full spectrum of strategies to achieve?

- The where—the geography of governing power: Our discussion explored this topic by asking, what is the pathway to scale? How would we imagine a progression or aggregation of power given multiple examples of municipal and/or state-level success? Although, even in city councils or state capitals where co-governance relationships exist, movement-friendly officials or allies do not typically represent a majority. The pathway to scaling governing power remains a key, open question.

- The why—the rationale of governing power: To what end do we pursue these strategies? A decade or two into investing in and developing our electoral capabilities, what is our assessment of the yield of our efforts? As one participant provocatively put it: Has our ability to organize and mobilize tens and hundreds of thousands into the streets diminished while we invested in voter mobilization? Is there a need for rebalancing and returning to the fundamentals of organizing?

Our movements are decades into building our capacities toward governing power. We are more sophisticated in our inside/outside strategies, and our toolbox is significantly expanded, with a proliferation of 501(c)(4)s and PACs.

How do we pause and plan for the decades to come, all while answering the immediate call to defend our civic system as it is, so we can build toward the multiracial democracy that remains unrealized? All while readying ourselves for the violent backlashes that will inevitably follow after each successive step forward? We know our organizations and movements must keep evolving, and simultaneously, so must our political institutions and parties. What does each stage, each phase of settlement look like, both internally and externally? We have only scratched the surface of these critical questions.