Restoring Democratic Institutions

April 29, 2025

By Roosevelt staff

‘Restoring Democratic Institutions’ is part of the 2025 Roosevelt essay collection: Restoring Economic Democracy: Progressive Ideas for Stability and Prosperity

(Martin Wheeler, Eye Em /Getty Images)

The roots of authoritarianism have grown cracks in our constitutional order and destabilized the foundation of democracy. The prevailing story on the Left points to Donald Trump as the main cause of this expansive destruction. And for good reasons. President Trump’s power-grabbing, norm-busting actions have been embraced by authoritarian leaders across the world. These leaders undermine independent judiciaries, delegitimize the press, and cast doubt on the integrity of elections. In the months since taking office, Trump has shown a willingness to flout the rule of law, exemplified most dramatically by his open defiance of court orders and his administration’s efforts to wrest the power of the purse from Congress and make unilateral government spending decisions.

But the story of America’s recent democratic decline did not begin with Trump’s descent from a gilded escalator in 2015. Trumpism’s triumph was born out of long-standing institutional vulnerabilities alongside deep social and economic divisions decades in the making. Indeed, Trump’s alarming political despotism is backlit by a more routine economic despotism that has pervaded American life over the last half century, upending the distribution of power in our society.

Through an unfair tax code and imbalanced markets, large corporations’ share of the nation’s wealth is growing—and with it, their influence on society. Companies have pursued sophisticated tax avoidance schemes to pay virtually nothing in federal income tax, undermining the faith in basic fairness that democracy requires. Mergers and consolidations have freed corporations from the burden of competition, giving them free rein to raise prices and limit consumer choice. In the name of profit, companies directly influence children, with social media corporations bringing in billions in ad revenue while putting children and teens’ mental health at risk from predatory algorithms.

These corporations don’t stop at enriching themselves—they subjugate workers, too. Corporate union busting thwarts the aspirations of some 60 million American workers who wish to form unions and exercise democracy in their workplaces. Along with preventing workers from collectively bargaining for their rights, employers also regularly steal their wages: A 2014 report from the Economic Policy Institute estimated that wage theft could cost American workers as much as $50 billion per year, and between 2021 and 2023 alone, the Department of Labor and various state agencies recovered $1.5 billion in wages illegally withheld from workers. Corporations further restrict workers’ freedom by instituting anticompetitive measures like noncompete agreements.

A democracy cannot withstand immense concentrations of power for long. These structural inequalities weigh down the functioning of our political institutions, too. Eli G. Rau and Susan Stokes recently argued that economic inequality is not merely a side effect of policy choices, but a fundamental driver of democratic erosion. Their research shows that as inequality rises, democratic institutions weaken—not just in struggling democracies but in established ones as well. The political scientists Jana Morgan and Nathan Kelly show that economic inequality is strongly associated with policy stagnation over time. As the top 1 percent captures a greater share of income, we see not only less action and less impactful action from our legislative bodies, but the policy action we do see is more inegalitarian. Perversely, deep inequality has the effect of making policy change more likely only when it favors economic elites. The outsized influence of economic elites shows up perhaps most dramatically in our elections. According to a recent report by Americans for Tax Fairness, election spending by billionaires has increased 160-fold since 2010, including a record $2.4 billion in 2024.

The world’s richest man, Elon Musk, who spent nearly $300 million to secure Trump’s electoral victory, now commands arguably the most powerful role in the federal government outside of the presidency itself. He has taken the practices of economic domination illustrated above directly to the federal government. He is treating the one enterprise we collectively own as a private business subject to his whims. Indeed, we are witnessing the logical conclusion of market supremacy, the near-total eclipse of private economic power over the power of the state that President Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to as “the essence of fascism.”

If democracy is fundamentally about people exercising agency over the decisions that govern their lives, then our economy—who it empowers and what it rewards—ought to be shaped by our democratic aspirations. The neoliberal conception of the economy as a self-regulating mechanism leads us to understand economics in natural, atmospheric terms—where phenomena like globalization, financialization, and deindustrialization sweep the nation like cold fronts—detached from public will. It sustains the myth of an economic system operating neutrally from politics and political decisions. If we instead understand the economy in democratic terms, then curbing private economic power and restoring agency to workers is imperative.

Democracy needs robust institutions, laws, and processes to work. But democracy is also an ethic, a practice, and a communicative culture. It requires, perhaps above all, trust that it actually works. The federal government—one of the few entities big and powerful enough to take on concentrated power and level the playing field—must be a catalyst for the restoration of this basic faith.

What would it mean to expand democracy beyond the voting booth, into the workplace and the policymaking arena? How might new avenues for public participation be paved and expanded? How can we resolve the tensions between participation and efficacy in order for government to deliver solutions that endure? And how can we commit to a new paradigm of democratic governance that rebuilds a common public square and a broadly inclusive conception of citizenship?

While the essays in this section begin to explore these questions, it would be impossible for any one collection to fully address the scale and stakes of our democratic crisis. Ultimately, these essays drive home the need for strong, democratic institutions inside and outside government that earn the trust and confidence of the public.

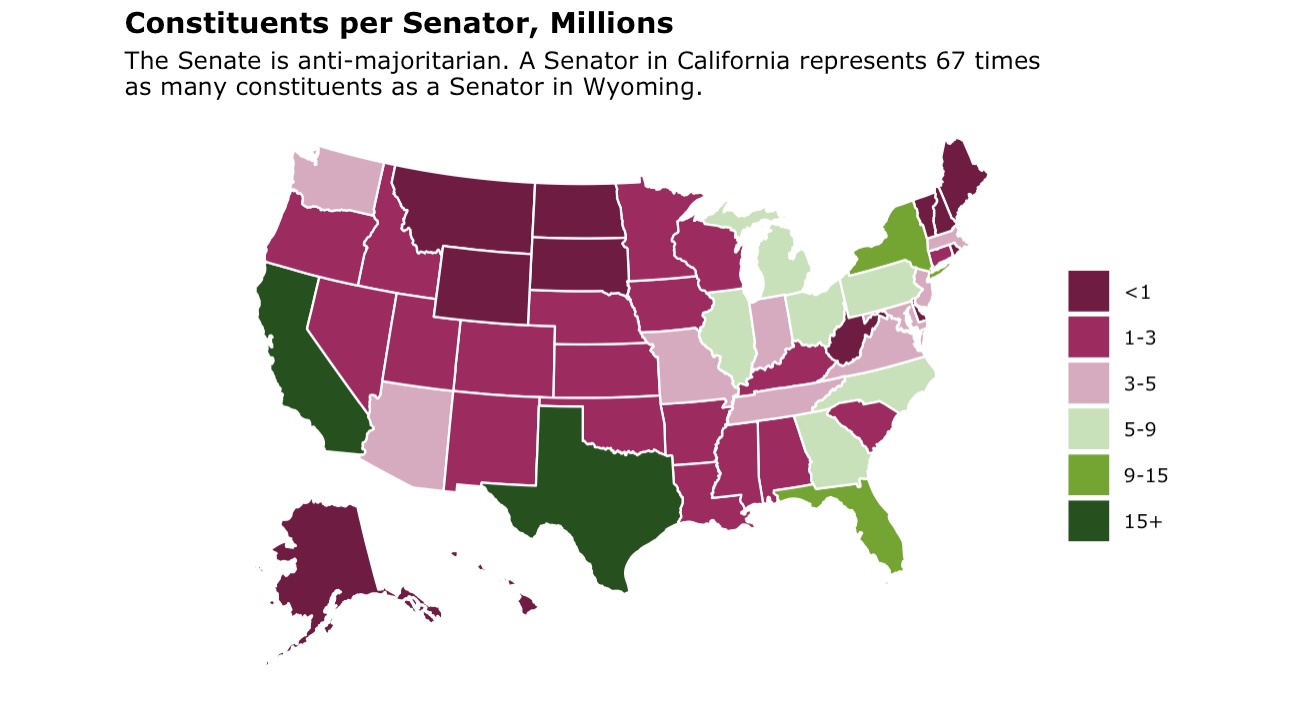

Core Government Institutions

The cracks in our democratic order are real, and they reinforce each other. Because of the Electoral College’s inherently undemocratic design, a president who lost the national popular vote was sworn into office twice this century. In Congress, the Senate gives equal voice to Wyoming and California, despite the latter having nearly 39 million more residents and the equivalent of the fifth-largest economy in the world. As Todd N. Tucker has argued, the Senate fundamentally fails to represent the American public on a one-person, one-vote basis. The rampant practice of gerrymandering congressional districts has a similarly antidemocratic effect in the House.

The anti-majoritarian character of the Senate has amplified the undemocratic nature of the most undemocratic branch of the federal government: the Supreme Court, where justices serve for life with few measures of public accountability. The high court has been packed with reactionaries—often through antidemocratic means, such as Mitch McConnell’s thwarting of a Democratic president’s power to fill a court vacancy in 2016—who use exceedingly novel legal theories to justify anti-worker and antidemocratic policies. Two of the court’s recent decisions stand out as being fundamentally at odds with democracy itself: Citizens United and Trump v. United States, which, respectively, gave corporations the right to spend unlimited amounts of money on elections, and declared that the president is practically above the law.

Preventing further democratic backsliding requires addressing each branch of government: legislative, judicial, and executive

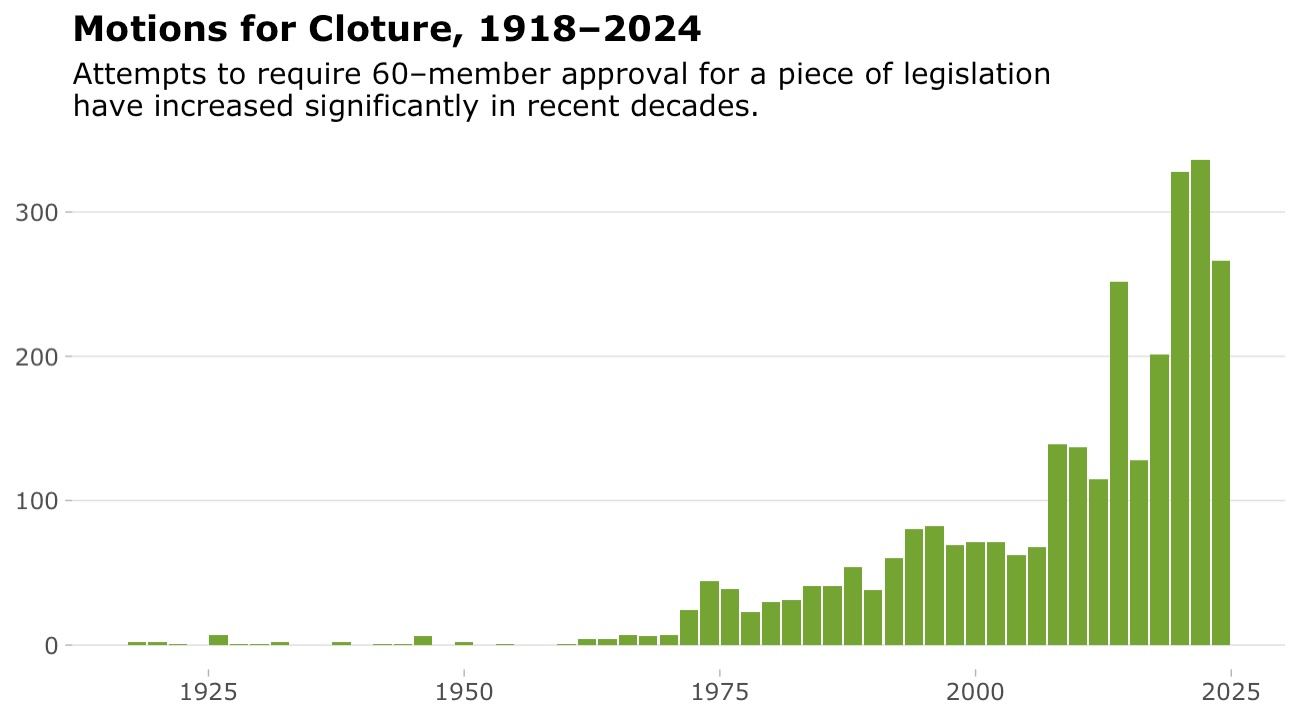

1) Restore democracy to the Senate and abolish the filibuster

Restructure the Senate so that a small minority of Americans don’t have an outsized voice in congressional decision-making.

Proposals for reforming the Senate range from outright abolition to minor procedural changes. The most urgent and practical reform is somewhere in between: abolition of the filibuster, a tool described by Tucker as “the most countermajoritarian procedure in the world’s most countermajoritarian second chamber.” The filibuster is a tactic that delays or prevents the Senate from voting on a bill. Such a delay can only be overcome with a 60-vote majority, which, in today’s intensely divided Senate, empowers legislators from the 20 or so least populous states to block anything backed by the vast majority of the country—often pro-worker policies. As the Senate becomes ever more malapportioned over time—by 2050, it’s estimated that 30 percent of Americans will elect 70 percent of the Senate—so will the filibuster’s anti-majoritarian effect on governing.

The Senate also provides no representation to the millions of American citizens who reside in Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico. DC already has a larger population than Vermont and Wyoming, as well as the means to be economically viable as a state, and Puerto Rico would be the 33rd largest state in the union if it were granted statehood. Importantly, the avenues for granting statehood to both are well within existing constitutional processes, and both could be achieved without a constitutional amendment.

2) Reform the Supreme Court and empower other governing bodies as effective counterweights

End juristocracy by mobilizing public power and treating courts as part of the broader political economy as opposed to neutral institutional referees.

As Brian Highsmith notes in this collection, the domination of the judiciary, juristocracy, has long been understood as reinforcing oligarchy. Efforts today to ameliorate economic inequality face similar risks of judicial veto by conservative justices who “received their lifetime appointments precisely because of their demonstrated hostility to such goals.” Reforming the court’s outsized role in our democracy will require not just institutional improvements, but newer pathways for the public to enact popular change. Highsmith points to states that give the people power to amend state constitutions, which in turn empowered public will to challenge the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision by enshrining abortion rights locally.

Providing the same pathways to public accountability toward the federal constitution would be an important check on courts’ outsized power. As Highsmith notes, “our Supreme Court wields a ‘super veto’ within our political system not simply because of what its justices can do . . . but also because other bodies, and the people themselves, cannot easily do the same.” Reforms to the court are reasonable and necessary—enacting binding ethics rules, staggered 18-year terms instead of lifetime appointments, and even court expansion. But the fundamental power imbalance will not be corrected if court reform is only limited to “reforming the courts.”

3) Build an executive branch fit for purpose

Reconstruct the executive branch to be accountable to the public and relentlessly focused on outcomes that build trust and enhance public power.

The current demolition of government functions, destructive as it may be, offers progressives an opportunity to go beyond restoration and embrace reconstruction. How can we (re)build state capacity to accomplish what we want government to actually accomplish? This also means eliminating harmful forms of state capacity—our immigration enforcement apparatus, for example, has persistently operated outside of public accountability, degrading civil liberties and trust in government. As Sabeel Rahman has argued, state capacity “has to be actively built, dismantled, and reimagined in light of our overarching vision for a just, inclusive democracy and economy.”

Much more can be done to reconceptualize the work of federal agencies. As Rahman also notes in “Rewiring Regulation: Regulatory Review for a New Political Economy,” how well agencies, and executive power more broadly, function on the back end significantly affects the implementation and efficacy of public policy. Of course, there is an inherent tension between efficacy, inclusion, and speed, but these goals can be thought of as mutually reinforcing. Ultimately, wherever possible, the state must empower the public rather than exclude it, protect rather than dominate, and respond rather than extract.

Finally, in this collection, LiJia Gong considers how our federal government can better serve democratic aspirations by changing its relationship to state and local governments. There are many policy problems that can be more quickly and responsively addressed by local action from directly affected communities rather than the federal government. But lack of access to sufficient revenue and financing mechanisms, as well as abusive preemption efforts from conservative state governments, hamstrings localities’ efforts to solve the problems closest to their residents’ lives. A built-for-purpose executive branch would better foster local action on issues like affordable housing and transit.

Essays on Core Government Institutions

Public Trust

Public trust in government is the cornerstone of a functioning democracy. Yet, in recent years, this trust has been eroded not only by deliberate efforts from the Right to undermine governmental institutions and sow social discord, but also by the state’s perceived inability to address significant, destabilizing challenges such as climate change and the cost of housing and health care.

Progressives’ vision for government must be couched in a broader vision for what constitutes the good life. Progressives must position government as an enabling force for a better, healthier, and more just society to regain the public’s trust and confidence. That work must begin with a clear articulation of the vision for society we are building toward, and action that shows we are moving forward to make that vision a reality.

1) Embrace a policy research agenda that is willing to reconsider long-held beliefs, centers Americans’ primary concerns, and upholds democratic values

Rebuild public trust by promoting policy solutions that speak to the realities, fears, and hopes of working people.

If we are serious about building trust, we need to start from the ground up: What do dignity and security mean to people? What do they understand as threats and why? What barriers do they face in securing dignified work, care, and belonging? And how might inherited policy frameworks get in the way of imagining better ways to meet people’s needs as they define them?

As communities experience rapid economic, technological, and climate change, policy research must be more attuned to how people experience rising costs and how they feel about growing uncertainty about the future. For example, we need more clear-eyed insights into how communities experience both immigration and immigration enforcement if we are to repair the harms of the Trump administration and foster a stable system going forward. We can lead with listening to the realities people face, and respond by putting forth a vision that is more humane and compatible with our democratic tradition as a nation of immigrants. In this collection, Cecilia Muñoz starts the conversation.

2) Offer policy solutions that build stability and community

Position policies to rebuild trust in both government and each other.

The Roosevelt Institute’s work on the cultural devastation of neoliberalism takes seriously the despair, mental health problems, overwork, addiction, loneliness, and social isolation that a neoliberal economy and society have wrought. As we look for policy solutions that rebuild trust in government, we must also pay attention to the way public policies can rebuild or undermine trust within our communities.

As Abdul El-Sayed argues in his essay, we can use health-care policy to address Americans’ epidemic of insecurity. By reshaping our health-care system from one of unequal access to one of shared care, and reclaiming the mantle of universal health care, we can articulate a broader conception of citizenship rooted in belonging. El-Sayed’s provocation should push us to look well beyond health care and ask how we can use public policy to foster connection and safety rather than division and insecurity.

Essays on Public Trust

Nongovernmental Institutions

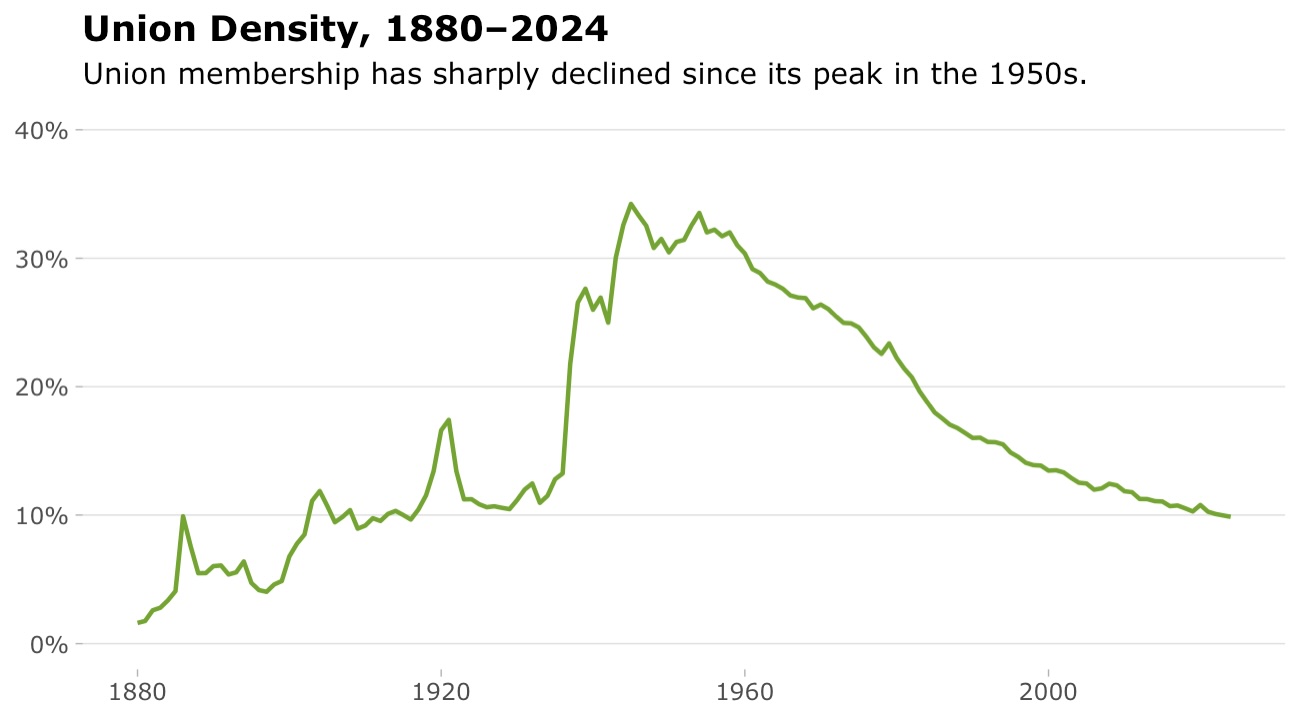

Democracy is being contested beyond just the three branches of government. If democracy requires more than a set of political institutions, then we must exercise the muscles of participation and deliberation in other spheres of life. It’s a common experience in the US for workers to head to the voting booth on an election Tuesday to choose their political representatives, only to return to a job in which they have little to no voice or representation. Today, only 6 percent of the private-sector workforce is unionized, down from roughly a third of workers in the middle of the century.

We must also recognize that before a citizen can vote, join a union, develop a stance on how a given policy might affect their lives, or even escape a natural disaster, they must know. The right to know is integrally tied with the right to participate in democracy. Yet today, the democratic imperative of an informed citizenry faces deep structural barriers. Dominant tech platforms control the flow of information—what people see on their feeds and what they do not—through opaque algorithms designed to harvest attention for profit. Billionaires buy up social media platforms and newspapers and repurpose them to serve their ideological and financial interests. Private equity firms buy struggling local newspapers and gut them, turning a quick profit by laying off staff and selling off assets. And while some promising models have emerged in nonprofit news, it’s not enough to offset the impact of losing nearly 3,000 newspapers since 2005, as Senator Chris Murphy cites in his introduction to this collection. We need free and effective media more than ever, but the deregulation, financialization, and concentration of our media sector have made it increasingly difficult to fulfill any of its public interest obligations.

1) Increase union density

Enhance democracy in the workplace and give workers a voice in shaping their livelihoods.

To usher in an era of truly democratic governance, we must expand the ethic of democracy into more parts of our society, especially the economic lives of workers. As Liz Shuler argues in her essay for this collection, unions are not just economic institutions—they are democratic institutions in their own right. And ensuring that workers have a seat at the table leads to better public policy. Through organizing, collective bargaining, and striking, unions serve as a bulwark against concentrated corporate power and an economy that only works for the ultra-wealthy.

To realize the full promise of unions, our legal system cannot be hostile to workers, and our labor laws must recognize every worker’s right to have a say. Rebuilding worker voice should include solutions like sectoral bargaining, which is more effective than firm-level bargaining at raising wages and reducing inequality. As the legal scholars Kate Andrias and Brishen Rogers note, Congress can expand the National Labor Relations Act to empower worker organizations to organize, bargain, and strike at the sectoral level, and empower the Department of Labor to consult with workers and employers to set wages and other minimum terms within industries.

At the same time, under current law, employers retain far too many tools to thwart unionization. Labor laws must be amended to require employers to provide unions with equal access to workers, while extending protections to domestic and agricultural workers and independent contractors who are more vulnerable to employer exploitation and abuse and currently excluded from protections.

2) Usher in an era of media democracy

Protect free speech from government interference and guard against media capture by powerful actors such as billionaires, platforms, and private equity firms.

Quality journalism is a public good worthy of robust, sustained public investment. In addition to nonprofit and commercial media, we should have public media institutions that insulate information from the pressures of profit and politicized influence and censorship. The Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB), which provides a small percentage of funding for PBS, NPR, and their member stations, was created in 1967 in part to serve the informational needs of the broad public. The CPB has faced waves of attacks over the years by opponents of public media, making public media stations more reliant on private funding sources. We should work not only to increase funding for our public media system, but to find ways to make it more independent and resilient against partisan attacks—including by reviving the original proposal for CPB funding, which would have come from a politically insulated trust fund rather than the annual congressional appropriations.

Restoring democracy to the information space also requires taking on Big Tech platforms’ outsized influence over the flow of information. In recent years, proponents of Big Tech regulation have proposed a series of measures to bring democratic accountability to platforms, from mandating they make public information on algorithmic decision-making to creating new regulators to oversee matters of transparency and privacy, complementing antitrust actions from agencies like the Federal Trade Commission and DOJ. Above all, it’s critical to prevent these platforms from becoming bigger and more powerful, acquiring their competitors, and collecting reams of user data with insufficient oversight on how they handle it.

Essay on

Nongovernmental Institutions