Boeing! Bombardier!! Bears!!!

September 28, 2017

By Todd Tucker

From a casual look at today’s business headlines, you’d think the Commerce Department had declared war on the world.

“The Commerce Department will slap stiff tariff on Bombardier’s new jet”

“Bombardier hit with 219% duty on sale of jets to Delta Air Lines”

“UK warns Boeing over Bombardier trade row”

“Bombardier stock watchers bracing for impact of US duties”

“Negotiators weigh NAFTA progress as Canada fumes over Bombardier”

“Not-so-special relationship? Trump puts America 1st, threatening 4,000 British jobs”

Is this Trumpism run amuck? In a word, no. Let’s all take a breath.

Here’s what we’re talking about: countervailing duties are legal remedies that allow importing countries to even out the distortionary effect of foreign subsidies, while anti-dumping duties do the same for products more generally that are being exported below their cost of production. What anti-trust rules are for uncompetitive markets domestically, these tools are for uncompetitive markets internationally. (Here, I use “competitive” in the Econ 101 sense of perfectly competitive markets without market power.) Both level the playing field. Yesterday’s Commerce Department decision sets the stage for 219% countervailing duties on 100- to 150-seat large civil aircraft from Canada.

This is indeed a big case in absolute and relative terms. The decision would nearly triple the $5.6 billion price on Delta Airlines’ planned purchase of Bombardier’s 100-person airplanes. And a quick perusal of the 416 anti-dumping / countervailing duties orders currently in place reveals few on this scale and only four against Bombardier’s home country of Canada. One of the more recent countervailing duty orders against Canada (from 2016) was over their asking price for polyethylene terephthalate resin. The 13.6% countervailing duties in that case didn’t raise the cost of soft drink bottles (one use for the chemical compound) into the billions.

But there is a lot of context missing from this coverage.

First, the decision is not some whim of Donald Trump’s. The petition was made by private sector company Boeing, and career civil servants at the Commerce Department made the determination of the 219% amount — which notably was higher than Boeing’s own estimate. The case landed on Commerce’s desk only after professional staff at the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC) made a preliminary determination. All four commissioners were unanimous in determining that Bombardier’s proposed imports would injure Boeing. This included Rhonda K. Schmidtlein, Chairman (a Democrat appointed by Obama), David S. Johanson, Vice Chairman (a Republican appointed by Obama), Irving A. Williamson (a Democrat appointed by Bush), and Meredith M. Broadbent (a Republican appointed by Obama). Not exactly Breitbart News, these.

Second, the number is not drawn out of thin air. The 219% number means that, in the Department’s expert estimation, foreign governments are subsidizing Bombardier’s planes to that amount. So, if the 219% number seems outrageous, it’s due to those governments’ interventions in the market. The detailed memo from James Maeder (the civil servant and Acting Deputy Assistant Secretary overseeing the investigation) identifies at least 13 policies by the Montreal, Quebecois, Canadian, U.K., and Northern Ireland governments that allowed Bombardier to operate with below market costs. This ranged from a direct investment by the public sector in Quebec (a 147.28% subsidy) to a “Training for Success” apprenticeship program by the Northern Ireland government (a 0.06% subsidy). The 13 programs added up to 219%.

Third, Commerce could be wrong. It’s possible that Maeder’s team got the math wrong. Maybe the Quebecois investment was only worth 113%, and the apprenticeship program only 0.001%. Maybe the total countervailing duty should be set at 170%. That would still be a high number and make for grabby headlines, but maybe that is actually the amount of subsidy.

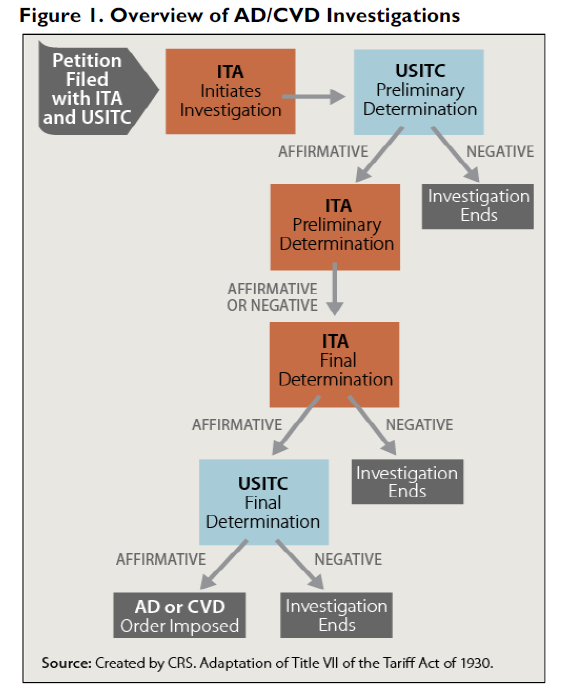

Fourth, if Commerce is wrong, there’s good news for Bombardier. Tuesday’s announcement was only the second in a series of many decision points. (We’re at the top right of the adjacent graph.)No countervailing orders have been collected yet, and the imports in question haven’t even arrived. The Commerce Department will make a final determination in December, at which point it gets kicked back to the independent ITC for its final determination, at which point Commerce will make its preliminary order final.

At any point along the way, the investigation could be shelved or duty lowered. (It’s true that cash worth the 219% will be held in escrow if Bombardier attempts to complete the transaction, refundable if the order is revoked.) Moreover, Bombardier can appeal the decisions to the U.S. Court of International Trade and all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. Both are comprised of life-tenured adjudicators appointed by mainstream presidents over the last few decades.*

And if the legal remedies weren’t enough, there are also political ones. Canada’s Justin Trudeau has threatened cancelling orders from Boeing, as has the U.K.’s defense minister. In each of these cases, domestic politics is factoring in. Theresa May’s minority government in the U.K. is hanging by the thread of their coalition partners in Northern Ireland (the DUP, who are leading the charge against Boeing). In Canada, Quebec’s provincial premier is calling for an all-out boycott of Boeing. This is a call Trudeau has to take seriously: without the 41 Liberal Party MPs from Quebec, his 54%, 181-seat parliamentary majority shrinks to 140 and 42%. That would make him a minority government just like May’s. Even in the U.S., Canada and Bombardier have mobilized their U.S. supply chain in Kansas and West Virginia — Trump states whose leaders have been weighing in with the ITC.

Pressuring Boeing is one thing. As Ted Alden hypothesized on Twitter, the U.K.’s threat to boycott Boeing indicates why, in retrospect, “Boeing never went after Airbus using US trade laws. The potential for escalation is huge.” And others have pointed out that Boeing’s case is more than a tad hypocritical, given its own considerable reliance on government support.

But pressuring Trump is another. As Ana Swanson recently reported in the NYT, “Unlike a recent ruling on solar tariffs, the case does not officially go to the president for a decision.” By complaining to Trump, Trudeau et al. appear to be soliciting the president to intervene in independent administrative law proceedings (or ultimately court proceedings) that he does not control.

In short, the fear (misplaced here) that U.S. policy might be Trumpified is leading to demands to actually Trumpify it. There are principled reasons to not like countervailing duties enforcement. But enforcement it is. One person’s “protectionism” is another person’s “rule of law.”

These are the laws we live under. If we don’t like them, we know how to change them.

But good luck doing that. These rules are very popular, and some scholars argue that (somewhat ironically) they are a political precondition for trade liberalization. Here’s political scientist Krzysztof J. Pelc in his excellent recent book “Making and Bending International Rules”:

antidumping is not an international-level competition policy. Rather, it is an alternate means of offering temporary import relief to industries when the ability to simply raise a tariff is constrained by international commitments. This “safety valve” function is the reason why antidumping falls in the realm of flexibility provisions. And indeed, there is growing agreement over the view that the safety valve aspect of AD serves an insurance function, tempering ex ante opposition to liberalization by import-competing producers, by acting as a promise to address shocks ex post. It is a means of completing the inevitably incomplete contract of any trade agreement. Domestic groups seek some reassurance that they have some recourse if the case they encounter a shock; in this case, an influx of goods sold below fair market prices. An antidumping regime is a promise to offer temporary protection in these cases. Empirical work supports the existence not only of the safety valve function, but of its effect on the odds of liberalization. As Kucik and Reinhardt (2008) demonstrate, countries with antidumping regimes are not only more likely to join trade agreements, but they also make more ambitious commitments when they do, as measured by the extent of tariff cuts they

commit to.

In short, if you like free trade, you’ll probably need to make peace with trade remedies — a trade-off that far preceded the Trump administration.

____