The Irreparable Damage Being Done to Federal Policy Research and Evaluation

March 5, 2025

By Stephen Nuñez

Though their goals obviously differed, Republican and Democratic administrations have for decades relied on the work of social scientists both within and outside the government to conduct research on policy cost and effectiveness. A small but crucial industry has developed to ensure policymakers understand the likely impacts of their proposals, the costs associated with implementing them, and the trade-offs they face. But right now the so-called Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) is canceling contracts and closing offices, leading to mass layoffs of evaluation scholars. In the process, it is destroying decades of institutional knowledge and expertise in exchange for the equivalent of the coins you might find between couch cushions.

OPRE, PD&R, IES. These acronyms likely don’t mean much to most Americans, but they are immediately recognizable to those who work in the field of policy research and evaluation. These are just a few of the offices within federal departments and agencies that do research, share data with the public, and issue grants and contracts to conduct large-scale experimental evaluations of policies like job training programs and middle school science curriculum reforms.

For example, IES is the Institute of Education Sciences, the office that manages research at the Department of Education. Since its founding under the George W. Bush administration in 2002, IES has provided funds to conduct large-scale evaluations of programs to raise community college graduation rates, improve K-12 math education, and more. It has also provided grants to researchers working to improve statistical tools used to identify the impacts of public policy. And their What Works Clearinghouse (WWC) initiative has set the standard for rating the quality of research and evidence associated with programs and policies and provided a template for other federal agencies to build on.

In February, however, DOGE set its sights on the Department of Education and abruptly canceled over $900 million in existing IES contracts. This was not limited to projects that “promoted diversity.” Reports suggested that IES is planning for mass layoffs and the shuttering of the WWC initiative. A similar story is playing out at other agencies DOGE has targeted: (planned) mass layoffs, suspension or cancellation of existing contracts and grants, and a promise of more to come at the Departments of Labor, Housing and Urban Development, Agriculture (which funds and oversees SNAP benefits), Health and Human Services, and the Social Security Administration.

Unlike those of us in the policy world, most Americans do not spend much time thinking about statistical methodologies, impact analyses, and evidence standards. And they shouldn’t have to. Evaluators help make the government work better so that people can worry about other things. However, everyone should care about and take notice of what is now happening in the federal offices that oversee such work. On the most basic level, hundreds of people have lost their jobs, and if this continues thousands more may lose their jobs for no good reason. This is not limited to federal employees. Over the past several decades an evaluation industry has sprung up to meet the research needs of the federal government along with those of state and local governments and foundations. Dozens of large and small businesses, nonprofits, and university research centers around the country have had their work suspended or canceled and are now faced with the prospect of layoffs or even bankruptcy.

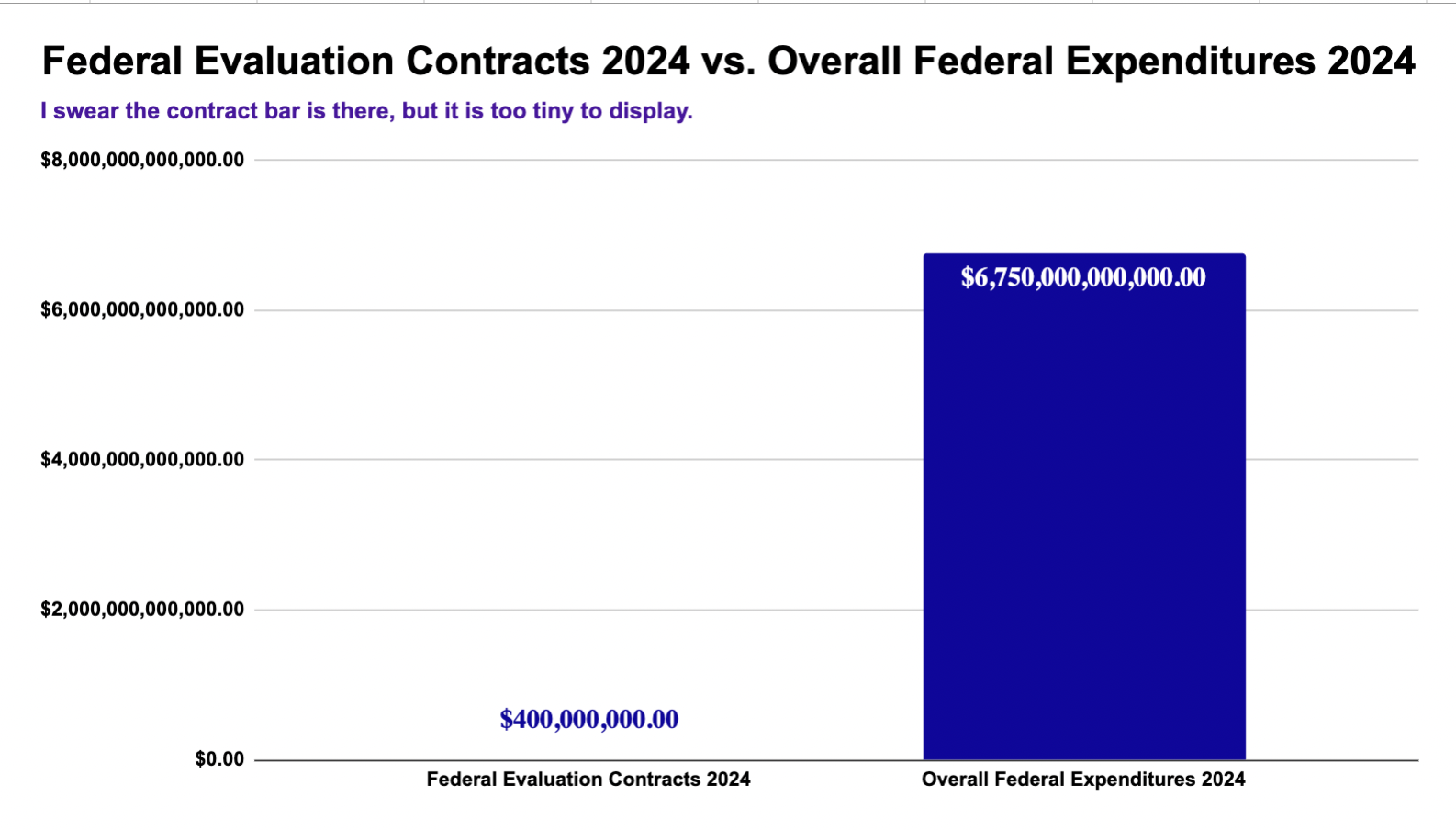

But beyond the direct costs to people’s livelihoods, the destruction of the federal government’s capacity to rigorously evaluate and improve upon its policies is a tragedy and is in direct conflict with DOGE’s stated aims. Eliminating federal evaluation spending would at most save a few hundred million dollars a year out of a more than $6 trillion budget. It would also blind the government to the effects of its own policies and, as a result, lead to waste and poorer outcomes for participants in federally funded programs and recipients of federal aid. It will mean scrapping federally funded research into programs that, for example, successfully reduce recidivism among returning citizens, help students graduate community college and do so more quickly, and help young adults find stable gainful employment. And it will be difficult to rebuild infrastructure that developed over decades, to recapture the specialized knowledge of researchers forced out and into early retirement, and to recover from the loss of talented young people who will decide on different careers.

The evaluation industry is not perfect. As a former evaluator, I have my share of critiques of the way policy evaluation is often conducted. There has sometimes been too much focus on the accuracy of impact estimates at the cost of their generalizability or magnitude, leading policymakers and researchers to focus on reforms that can be studied using the most reliable methods (like randomized controlled trials) but that ironically are least likely to work. Qualitative research to understand how and why programs work and whether they can be effectively scaled has not received the same funding support as quantitative research despite being essential to opening up the “black box” of impact analysis. And researchers too rarely consider the lived experience of intended beneficiaries—their needs, desires, and expertise—robbing us of the sorts of insights that can serve as a necessary reality check to policymakers when crafting a reform.

But evaluation work is at its core a good and necessary thing; the field needs modest reforms, not scuttling. And, indeed, major changes have been underway over the past several years, with federally funded initiatives focused on each of these issues. This, not coincidentally, coincided with the influx of a new generation of researchers from a more diverse set of racial, economic, and disciplinary backgrounds. It’s awful to think that we might throw away all this expertise and all this potential for pocket change.