We Can’t Deregulate Our Way Out of Childcare Market Failures

February 25, 2025

By Elliot Haspel

Childcare is a sector in flux. Since the 1960s, when mothers of young children first began entering the external labor force in large numbers, it has been treated largely as a market good as opposed to a social good akin to schools, libraries, and parks. After the failure of the 1971 Comprehensive Child Development Act, federal policy has considered childcare as a private good, primarily providing access as a component of the welfare system, leveraging vouchers that further marketize the sector. However, childcare does not and cannot effectively function as a market; indeed, it is what former US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen calls a “textbook example of a failed market.” While there are surely areas of needed regulatory reform, we cannot deregulate or demand our way out of immutable market failure. Instead, a robust public investment in supply-side interventions is essential.

A larger public role for childcare is crucial

Quite simply, childcare markets do not and cannot effectively meet the needs of children, parents, providers, communities, and the economy.

Childcare markets don’t work because even with high demand, few consumers can bear the true cost of operating high-quality programs. Childcare markets don’t work because quality is important yet difficult to discern, and with limited supply consumers can hardly take their business elsewhere. Childcare markets don’t work because parents don’t have years to save for childcare tuition, and you couldn’t get a loan for childcare if you tried. With so many market failures resting on a fundamental miscasting of childcare as a merely instrumental service, the only path toward abundance is through robust public support. Journalist Annie Lowrey put it well when she wrote, “the math does not work. It will never work. No other country makes it work without a major investment from the government.”

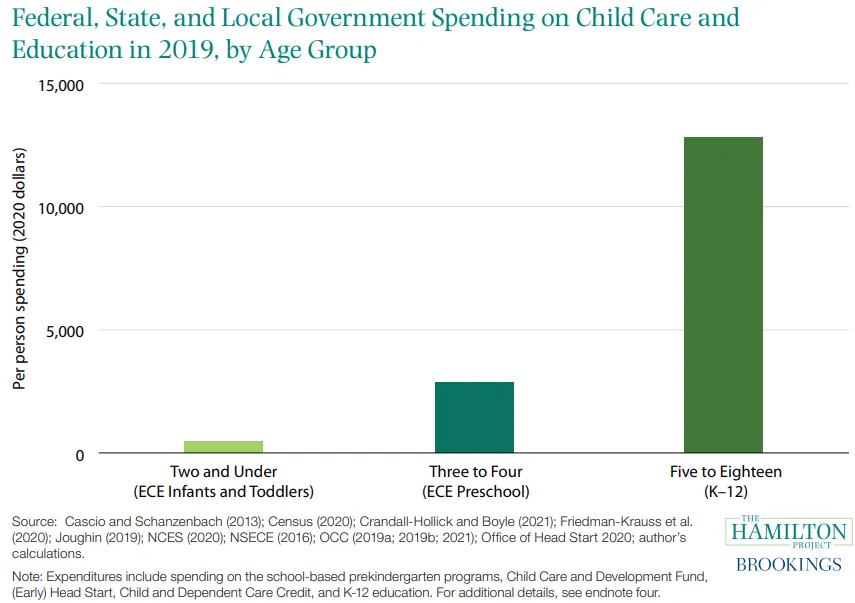

Unfortunately in the US, childcare simply lacks the degree of permanent public funding required to meet parent needs and deliver a consistently high-quality product. The US invests less in childcare, as a percentage of GDP, than most high-income nations. Even when considered in context of US spending on children and families, childcare comes up absurdly short:

But more money in the system is not enough on its own

Where and how that money flows matters. For instance, expanding supply by building or expanding facilities is difficult and would-be childcare providers face a steep climb because there is very little funding available for start-up costs or capital improvements. The Child Care and Development Block Grant, the main source of US childcare funding, statutorily prohibits recipients from using the funds to purchase land or conduct major construction activities. The lack of widespread capital is doubly problematic because childcare facilities can, when well-supported, serve as important community assets and social infrastructure.

What’s more, access to capital is one reason why investor-backed for-profit chains, including those owned by private equity firms, have a distinct competitive advantage. The more that nonprofit and community-based providers struggle with capital scarcity, the more market share that profit-maximizing entities are likely to gain; and if the history of private equity in other human services is any guide, this bodes poorly for American children and families.

While more capital is important, childcare costs are concentrated in wages—not because providers earn high wages, but because it takes many staff to do the hard work of cultivating young developing bodies and brains. Increasing voucher reimbursement rates may have a modestly positive indirect effect on provider wages, but childcare educator pay remains among the lowest 5 percent of all occupations, leading to high turnover and widespread shortages. Since both adequate facilities and staff are prerequisites for a childcare program’s legal operations—to say nothing of quality that promotes child development—the lack thereof is a direct supply constraint.

Deregulation cannot solve market failures

In the face of low childcare supply, there have been increasing calls—on both sides of the aisle —for deregulation, ostensibly based on a theory that overregulation is choking supply. This is a place to hold two truths in tension: There are legitimate steps that need to be taken to modernize childcare regulations and smooth the path for provider openings, and deregulation cannot solve childcare’s fundamental market failure. There certainly are some regulations that need revision, whether extraneous zoning requirements that delay licensing approval or obsolete regulations such as an Illinois mandate that providers carry coins on walks to use pay phones in case of emergency.

However, the regulations that most significantly drive costs should be considered nonnegotiable: those related to health and safety, and in particular the need to maintain low child-to-adult ratios. As advocate and childcare communications expert Katie Albitz has explained, too much deregulation can actually work counter to the building of a holistic, healthy system: “Deregulation creates unsafe conditions, then [opponents can exploit] the danger and tragedy that follows to erode public support, weakening the case for government investment and demonizing mothers who rely on it.” A well-designed regulatory system is particularly crucial in maintaining quality and trust for a sector where the individuals being served are often preverbal or otherwise unable to communicate if harm is occurring.

What a supply-side abundance agenda for childcare could look like

There are, thankfully, precedents around the country and world that point toward a better path. In Michigan, Gov. Whitmer’s administration leveraged $100 million in pandemic-era funds for an initiative called Caring for MI Future, which included facility grants, start-up support, and business assistance. In total, 3,600 programs in the state were either launched or expanded. Massachusetts offers most programs in the state “Commonwealth Cares for Children” grants to support their ongoing operations—carrying on a successful legacy of ARPA stabilization grants—with an average monthly award of around $12,000. Owing largely to this $475 million annual fund, the Bay State has seen an increase of 45,000 childcare slots since 2021.

Moreover, Washington, DC, provides direct wage supplements and access to free or low-cost health care for the city’s childcare educators through its Pay Equity Fund; the Fund has resulted in markedly improved recruitment and lower turnover, and has been shown to have a return on investment of at least 23 percent. Oregon used ARPA funds to bring childcare providers into a state retirement pool and seed their accounts, while Oklahoma temporarily paid family, friend, and neighbor (FFN) caregivers of essential workers. (FFNs are a key part of the childcare supply ecosystem—as are stay-at-home parents—often neglected by public policy.)

It’s not just the US, either: Supply-side actions like operational grants and wage supplements have become cornerstones of international childcare reform. That’s true in peer nations that also have historically marketized childcare, whether Canada’s new “$10 a Day” system or Ireland’s recent “core funding” model.

A final place for governments to consider getting involved is through the direct provision of childcare services. Outside of university settings, Head Start, and state pre-K, public provision of childcare is rare (pre-K, notably, has proved hugely popular and brought significant benefits for families). But there is no particular reason municipal or state governments couldn’t purchase or launch childcare programs and either operate them or turn them over to a trusted nonprofit provider. Similarly, worker and parent childcare co-ops are relatively common in countries like New Zealand (making up over 10 percent of the Kiwi sector) but vanishingly rare here. The lack of a public option or co-ops—and the resulting lack of alternatives for independent owners who wish to sell—is another reason why investor-backed for-profit chains are steadily gaining ground.

There are no easy or cheap solutions to the nation’s childcare challenges. That does not mean we should chase fake answers. There are parts of the economy where shrinking governments’ role can increase supply and lower costs, but there are others, very much including childcare, where the need for more supply calls for a larger public role. Childcare is too important—for children, for families, for communities, for economies—to pretend we can deregulate our way out of the need for public investment or rely purely on demand-side interventions. Americans deserve a childcare system marked by an abundance of high-quality options, not scarcity, profit-maximizers, and the illusion of choice. We would do well to develop a holistic supply-side agenda that pushes on multiple parts of the system and, in doing so, moves childcare away from its unyielding market failure.