Entrenched Power: How Shareholder-Owned Electric Utilities Hinder the Clean Energy Transition

September 19, 2024

By Niko Lusiani

I. Introduction

The United States is in the beginning stages of a momentous energy transition. In the next few decades, our country must move away from an arcane, centralized, fossil fuel–based energy system and toward a more decentralized, renewable system promising to “electrify everything”—from heating, to cooking, to transport, to data processing, and beyond. Expanding renewable sources of electricity has been a centerpiece of the Biden administration’s climate industrial policy, and is especially critical as the country faces an unexpected surge in peak load demand from booming manufacturing, as well as from AI data processing and broader end-use electrification (Plumer and Popovich 2024; Halper 2024; Lee et al. 2023).

This boom in electricity demand is prompting a knee-jerk reaction from the utility industry to retain existing gas-fired power plants or to build new ones, further locking in fossil fuel power generation. These steps are antithetical to decarbonization goals, which require a rapid drawdown in oil, gas, and coal paired with rapid and sustained clean energy investments.

Bringing renewable energy supply on fast enough to not only keep pace with increasing demand but also replace the toxic legacies of existing fossil fuel generation—at a cost consumers can afford—is imperative. So what obstacles are stopping this process from happening?

This brief explores the role of consolidated investor-owned electric utilities as gatekeepers actively slowing—or in some cases outright blocking—the renewable energy build-out and working against the implementation of essential climate change policies such as the Inflation Reduction Act. It finds that this gatekeeper status—and governance failures surrounding it—allows utilities and their transmission organizations to control two key operational levers that determine the speed and cost of renewables: interconnection and transmission. All else being equal, the current incentive structure leads incumbent utilities to prefer developing slow, expensive, fossil fuel–based infrastructure that they can control within their captive footprints, while also blocking new, cheaper, renewable infrastructure developed by a suite of different actors and transmitted over new, interregional power lines. This brief sketches out how and why investor-owned electric utilities abuse their position as incumbents to impose unnecessary bottlenecks that slow and inflate the cost of the energy transition. It then provides proposals for how local, state, and federal governments can shift incentive structures to overcome these bottlenecks, reduce utility bills for families, and accelerate the renewable energy transition.

Investor-owned electric utilities are abusing their positions—imposing unnecessary bottlenecks that inflate the cost of and slow the energy transition. State and federal governments have the power to shift incentive structures to overcome these bottlenecks and accelerate the renewable energy transition.

II. The Benefits and Challenges of a 21st-Century Clean Energy Grid

To reach the overall goal of net-zero emissions by 2050, the US must double its share of electricity generated by non-carbon-emitting sources by 2030 (National Academies 2021). This means that roughly 1,000 gigawatts (GW) of wind and solar need to be sited, built, and connected to the grid by 2030.1 To put that in perspective, the US currently has 1,279 GW of installed electric generation capacity. While doubling the country’s electricity capacity with renewables in under a decade may seem insurmountable, innovation and policy headwinds are helping. Renewable electricity generation is now cheaper than other energy sources (Abhyankar et al. 2021), and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has provided a historic influx of funding and financing options to build renewable energy infrastructure across the country. A few utility companies are responding to IRA incentives by leaning into utility-scale clean energy. Florida Power and Light, for example, is on track to replace about a third of its existing fossil generation with renewables by 2030, according to the Sierra Club. While the company still has a long way to go toward 100 percent clean energy, IRA provisions have helped it bring down the costs of solar and wind by over a third, allowing it to pass on some of these savings to customers (Fogler and Ver Beek 2023). But this example of progress is rare. The pace of bringing on renewable energy generation in the US is still too slow, and utility companies are often to blame.

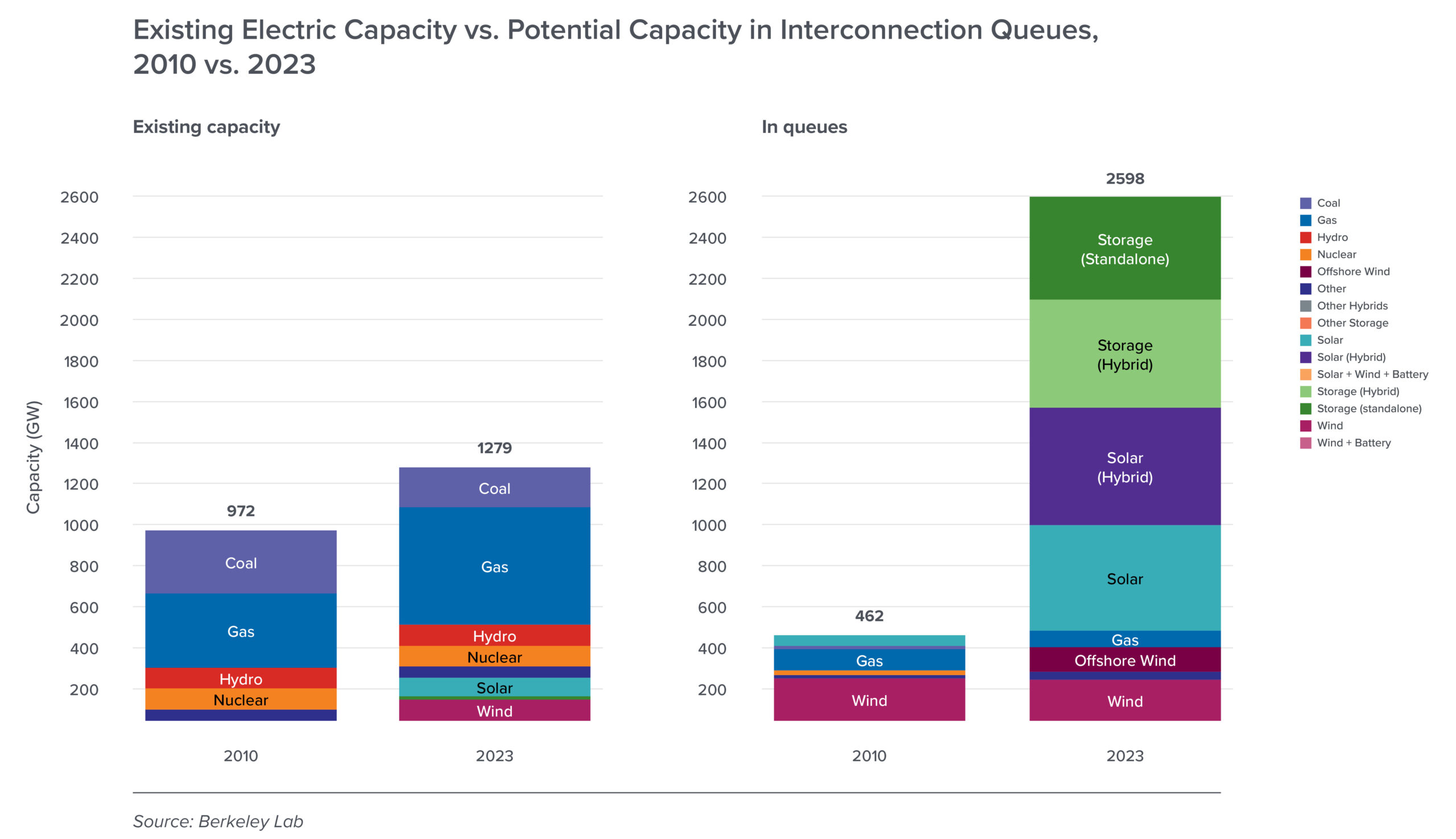

Despite the fact that the cost of generating electricity from renewables is now lower than fossil fuel generation, renewable energy developers face widespread challenges (Christophers 2024). As this brief will explore, one main challenge to clean energy deployment is the long and convoluted process to connect new energy projects to the grid. Almost 2,500 GWs of potential renewable generation and untapped storage capacity is waiting for authorization to connect to the grid (Rand et al. 2024). That’s about double the entire 1,279 GW of electric generation capacity currently installed nationwide—just waiting in line, mired in energy purgatory without permission to launch projects.

Figure 1. Source: Rand et al. 2024; Berkeley Lab 2024

Untapped, unbuilt renewable resources make up 95 percent of the electricity in these queues today. Only 5 percent of new projects awaiting permission are fossil fuel–based (Rand et al. 2024). As Figure 1 illustrates, the bottleneck remains in the actual build-out of those new zero-carbon resources like solar, wind, and battery storage. Only one-fifth of projects requesting interconnection from 2000 to 2018 reached commercial operations by the end of 2023, and the typical project took nearly five years to be interconnected (Rand et al. 2024).

In the words of the US Department of Energy (DOE), “the grid is becoming a bottleneck to greater economic development, decarbonization, and equity priorities” (White et al. 2024). Without a swift increase of clean energy supply to meet the current upsurge in demand, electricity costs on consumers and on businesses will only increase. Next year, household electricity prices are forecast to reach their highest level in nearly 30 years (Welton 2024), with Black, Indigenous, and Latinx households paying, on average, higher energy costs as a fraction of income than white households (Farrell 2024). An economy run on affordable, clean electricity, on the other hand, will not only reduce the volatility of energy price inputs across the economy (Melodia and Karlsson 2023; Weber et al. 2022) but also significantly reduce the burden on the one in seven US families currently unable to afford their electricity bills (Rubin, Freed, and Aggarwal 2023).

Accelerating the renewable build-out, if governed in the public interest, could save US households upwards of $5 billion per year (Bourgoin et al. 2022).

The widespread economic benefits of a clean energy grid are clear. And if even a third of the renewable projects currently in the interconnection queue were allowed to move forward, we would be well on our way to meeting our goals to decarbonize electricity generation in the face of growing demand. Who or what, then, is standing in the way of unlocking the renewable energy build-out? Experts point to the interconnection and transmission expansion processes—and the influence of incumbent utility companies over such processes—as key bottlenecks posing unnecessary constraints on the renewable build-out, as well as processes that increase the costs of renewable electricity compared to fossil fuels (Deese 2024; Bozuwa and Mulvaney 2023; Kovvali and Macey 2023; Peskoe 2023b; Welton 2021).

Since regulatory changes in the mid-1980s, several hundred independent, local electricity companies have now merged down into today’s roughly 40 utility conglomerates—most of which are multistate, multinational holding corporations (Hempling 2018). Even though some have sold their generation assets, these large incumbent utilities still sit at the center of supply and end-use of electricity—acting as gatekeepers of our energy system.

This brief zeroes in on the current incentive structures driving the harmful business practices of these incumbent utilities to effectively discriminate against independent renewable energy producers in favor of themselves and their shareholders. Section III explores how utility monopolies slow and inflate the cost of the energy transition through their inordinate influence over interconnection and transmission decisions. Section IV discusses why it is currently in the financial interest of these gatekeeping businesses to protect the status quo and prevent an energy transition. And section V provides a suite of policy options that—in tandem or separately—would advance a new paradigm for utility governance that benefits current and future generations of American households, businesses, and the economy as a whole.

How Utility Companies Slow Interconnections

#1

Overly complex and ambiguous interconnection standards require extensive technical expertise and resources that smaller renewable energy developers may not have the capacity to navigate.

#2

Utilities and RTOs often fail to disclose essential information critical to the interconnection processes, such as the most cost-effective locations to connect to the grid. This information opacity makes an already complex process even more difficult to understand, creating a chilling effect on renewable development.

#3

Interconnection has become an unreasonably expensive endeavor, with utilities hiking costs unexpectedly and unjustifiably in several cases. In the midwestern and southern regions encompassing the territory of the Midcontinent Independent System Operator (MISO) organization, utilities have been found to be “cooking the books” with local criteria in order to saddle independent generators with additional costs. The possibility of surprise fees understandably deters developers and customers.

#4

Utilities and RTOs have created an unnecessarily slow, time-intensive interconnection process, with few mandates to complete them swiftly. Xcel Energy’s insistence that they must evaluate one project at a time per substation bogged down the interconnection process in Minnesota so much that state regulators had to issue a formal order to do a cluster study to speed up the process.

Footnotes and Suggested Citation

Read the footnotes

1This brief focuses its analysis on “traditional” renewable electricity–generating resources, namely solar and wind. Other non-carbon-emitting resources, such as nuclear or green hydrogen, as well as battery storage systems, are outside the brief’s scope.

Suggested Citation

Lusiani, Niko. 2024. “Entrenched Power: How Shareholder-Owned Electric Utilities Hinder the Clean Energy Transition.” Roosevelt Institute, September 19, 2024.

Related Resources

(Opens in a new window) Energy Price Stability: The Peril of Fossil Fuels and the Promise of Renewables

May 11, 2022

By Lauren Melodia, Kristina Karlsson

(Opens in a new window) Sea Change: How a New Economics Went Mainstream

November 16, 2023

By Felicia Wong, Suzanne Kahn, Mike Konczal, Matt Hughes

(Opens in a new window) Lessons from Abroad: What US Policymakers Can Learn from International Examples of Democratic Governance

October 12, 2023

By Shahrzad Shams, Johanna Bozuwa, Isabel Estevez, Carla Santos Skandier, Patrick Bigger

Author

Niko Lusiani

Former Director, Corporate PowerNiko Lusiani is the former director of the corporate power program at the Roosevelt Institute, where he led research focused on corporate power and its impact on the economy.