Restoring a Democratic Economy

April 29, 2025

By Roosevelt staff

‘Restoring a Democratic Economy’ is part of the 2025 Roosevelt essay collection: Restoring Economic Democracy: Progressive Ideas for Stability and Prosperity

(Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

In the 1930s, the deep wounds of the Great Depression ignited a global competition of ideas about markets. In the unrestrained capitalist model that precipitated the depression in the US, society was subordinate to profit. What ultimately triumphed here was Franklin D. Roosevelt’s vision of a democratic economy: one in which we shape markets to serve the public good and drive innovation and shared prosperity. That model, exported to democracies following World War II, delivered rising living standards, increasing opportunities, and greater freedoms around the world for half a century.

Today, that model is under threat—not just from the neoliberal forces that shifted power toward unfettered markets but from surging authoritarian forces. Abroad, models of competitive authoritarianism have made significant inroads, while China’s model of state capitalism has been more responsive to rapidly changing circumstances and dramatically outperformed the West following the Great Recession. At home, a second Trump administration has married conventional upward redistribution with a regime openly pushing corporations to carry out its political project.

Rebuilding faith in democracy will take more than economic deliverism alone. But effective, publicly shaped, and public-serving markets are necessary to restoring a stable democratic economy in the US and once again showing the world why we chose it over authoritarianism in the first place.

To renew the promise of a New Deal–style democratic economy—fusing an independent, democratically guided private sector with a capable, democratic state—policymakers must reassert the role of democratic society in shaping markets. They must recommit to American values, this time with smarter theories, better data, and new policy instruments.

Beginning with minimum wage research in the 1990s, a revolution in empirical economics identified opportunities to make our economy more equitable, humane, and efficient—from labor policy to taxes to income supports. In addition, the past two decades of painful lessons from the Great Recession and pandemic have offered new evidence and perspectives on macroeconomic orthodoxy. Two long-term trends—America’s multigenerational war on organized labor and inflation moderation—look much more like a coincidence than the connected phenomena neoliberal thinkers claimed. At the same time, the jobless recoveries of the past three decades appear, like so much of US macroeconomic policy, to be more of a policy choice than an irresistible force of technology and globalization.

These lessons inform the essays in this section, which explores a combination of policies and outcomes in pursuit of a more democratic economy. A democratic economy is not an objective to be achieved but a framework for the evolving process of shaping markets to serve public needs. And there is no one-size-fits-all approach to doing so, as these ideologically diverse essays showcase. Despite their diversity, these essays share three overarching goals: protecting workers and fostering abundant high-quality jobs, controlling the cost of living, and creating a safety net that ensures a strong economy leaves no one behind, including those who cannot work and who take care of others. A democratic economy requires not only that we meet these goals but also that we disrupt the neoclassical paradigm that led to decades of underwhelming economic growth and skyrocketing inequality in the 21st century.

High-Quality Jobs and Good Wages

The 21st century has been dominated by two sides of a cost-of-living crisis—first by inadequate job and wage growth that created grinding cost pressures, then by acute price shocks during the pandemic and recovery—with new threats of policy-induced cost pressures to come. A democratic economy calls for acting on all fronts to guarantee opportunity and affordability—beginning with policies to ensure full employment, spur broad real wage growth, and address the challenges of new technologies that threaten workers’ well-being.

1) Prioritize full employment

Policies that foster tight labor markets build a more equitable economy for all.

Progressives should be proud of the rapid return to full employment in 2021, the first time since the 1980s the US has escaped a recession without a jobless recovery, and build on this success. In his essay for this collection, Arindrajit Dube details the costs of American policymakers’ learned helplessness on macroeconomics and explains how the recent return of full employment as both a policy objective and an outcome has yielded broad benefits—to the economy in general and workers in particular.

The benefits of full employment are many—especially to growing companies, which benefit from larger markets—but additional attention is needed to ensure all Americans can enjoy the benefits of a full employment economy. Further, affordability means not just maintaining lower costs but ensuring that the wealthy don’t bid up the costs of living for all Americans and that the government is adequately funded to shape competitive markets and provide economic security.

2) Focus on wage growth

Good jobs with growing incomes are a prerequisite for confronting any cost-of-living crisis.

For the first two decades of the 21st century, US recoveries were weak, leading to employment shortfalls and sluggish wage growth. While this period produced some of the lowest sustained inflation rates in history, weak income growth for all but the wealthiest Americans meant little progress on affordability overall. Coupled with a weak commitment to full employment, an assault on organized labor further chipped away at incomes, even as rising costs of housing, education, and childcare squeezed families. Inflation in both the COVID-19 recession and recovery has led to a renewed focus on the costs side of affordability, but, without the rising incomes that precipitate a tight labor market and worker power, cost savings will never be enough to deliver affordability.

3) Give workers a say in AI deployment

New technologies can empower and improve workers’ lives, but only if workers have a say in design and deployment.

Technological advances, including “artificial intelligence,” are already affecting workers across sectors. In some cases, these new technologies could be a genuine boon to worker productivity, job satisfaction, and industrial progress. Yet too often these technologies are deployed with little consideration for workers’ well-being, needs, or safety, often eliminating jobs altogether. For example, in health care, one of the largest labor sectors in the country, AI-powered “algorithmic management tools” have been deployed across hospitals in an attempt to turn nursing work into an Uber-style gig economy.

Sharon Block and Michelle Miller argue that, in order to truly lead to strong economic growth and address our growing labor needs, new technology must be designed in partnership with workers themselves. When workers have a voice in both the design and deployment of technologies, they can identify where technology helps or hinders their efficiency. And when new technology really does lead to wholesale worker displacement, progressives must respond with support systems that maintain worker dignity and offer new paths to societal contributions.

Essays on Jobs and Wages

The Cost of Living

The successful response to the COVID-19 recession suggested that economists had moved toward cracking the fundamental policy challenge of one generation; now we must respond to the cost challenges faced by everyday Americans—both those that have been obvious for decades and those that lingered underneath the surface in an economy short of full employment.

A democratic economy calls for a government that addresses the costs of everyday living and major life events. This means standing up for workers and consumers against corporations, both through shaping competitive markets and through public provision of key goods. And it calls for a mix of traditional and new approaches to ensure Americans are protected against market failures and anticompetitive business practices, as Elizabeth Pancotti and Alex Jacquez explore in their essay. Classical approaches to regulation and enforcement must be strengthened and expanded to guard against new threats, like sellers’ inflation. In addition to shaping key markets like energy, housing, and health care, public provision remains a crucial and too often overlooked tool.

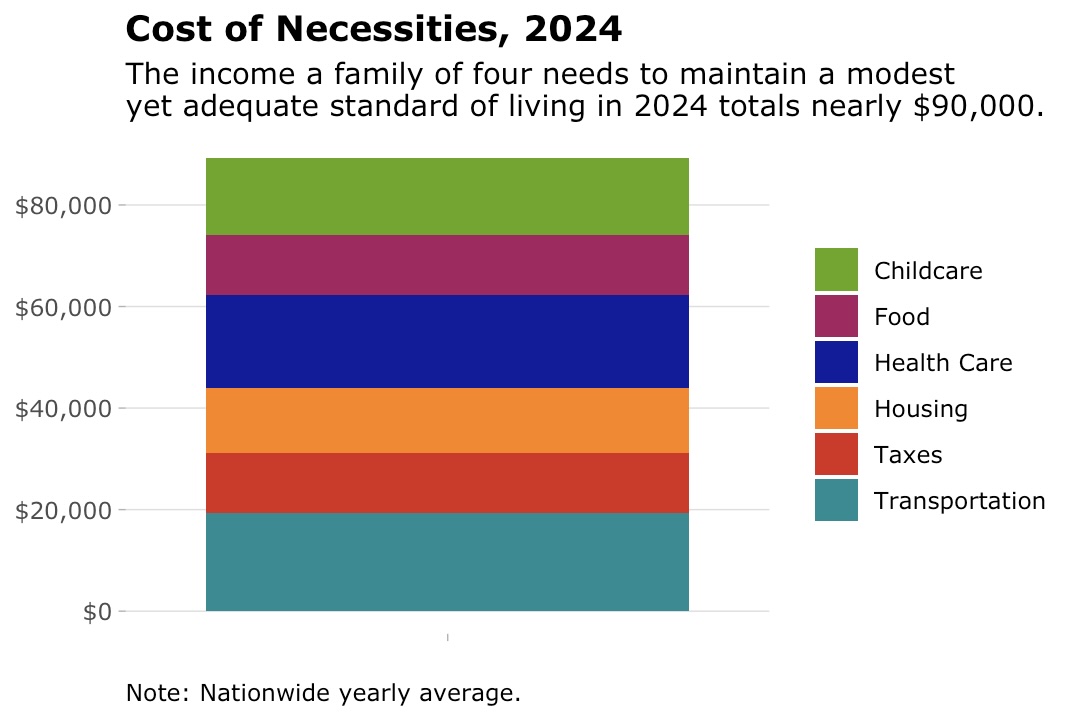

Beyond lowering costs at the macro level, progressives need to address the long-standing cost of needs crisis. For decades, the US economy has delivered rising costs for the essentials in life, like housing, health care, college, and childcare, and falling costs in discretionary goods. This is not a matter of debate—it’s often studied and discussed by economists with different political views.

1) Fight inflation on everyday goods

Lowering costs requires creative market interventions that expand our policy tool kit.

In spite of a 2024 campaign heavily focused on costs, policy from the current administration and Congress is poised to make these costs worse. Progressive solutions must be ambitious and multifaceted in response. Pancotti and Jacquez offer multiple approaches to bringing down costs for all families, including negotiating directly with producers and distributors to keep basic food items affordable for all, enforcing antitrust against corporate grocery chains engaging in unfair or anticompetitive pricing, and reviving the fight against “junk fees.”

2) Value price stability as much as lower costs

Keeping prices predictable requires modernized commodities security.

Affordability is also more than one number. Prices that jump around over time are costly themselves. Disruption may sound great in the boardroom, but it can be devastating for families. A progressive approach to affordability means thinking about how to make costs for everyday items like groceries and energy less volatile, and it means ensuring that families that save for college, a home, and retirement can make long-term plans.

To protect consumers from the worst effects of market volatility, Arnab Datta and Alex Turnbull suggest we reimagine the Strategic Petroleum Reserve as a Strategic Resilience Reserve. This reserve, “integrated with modern financial markets and supply chains, could support the development of well-governed, resilient markets for critical commodities.” Crucially, it would protect consumers from price spikes while offering producers greater security in long-term investments, and it would help us store commodities like lithium and cobalt that are vital to a decarbonized economy.

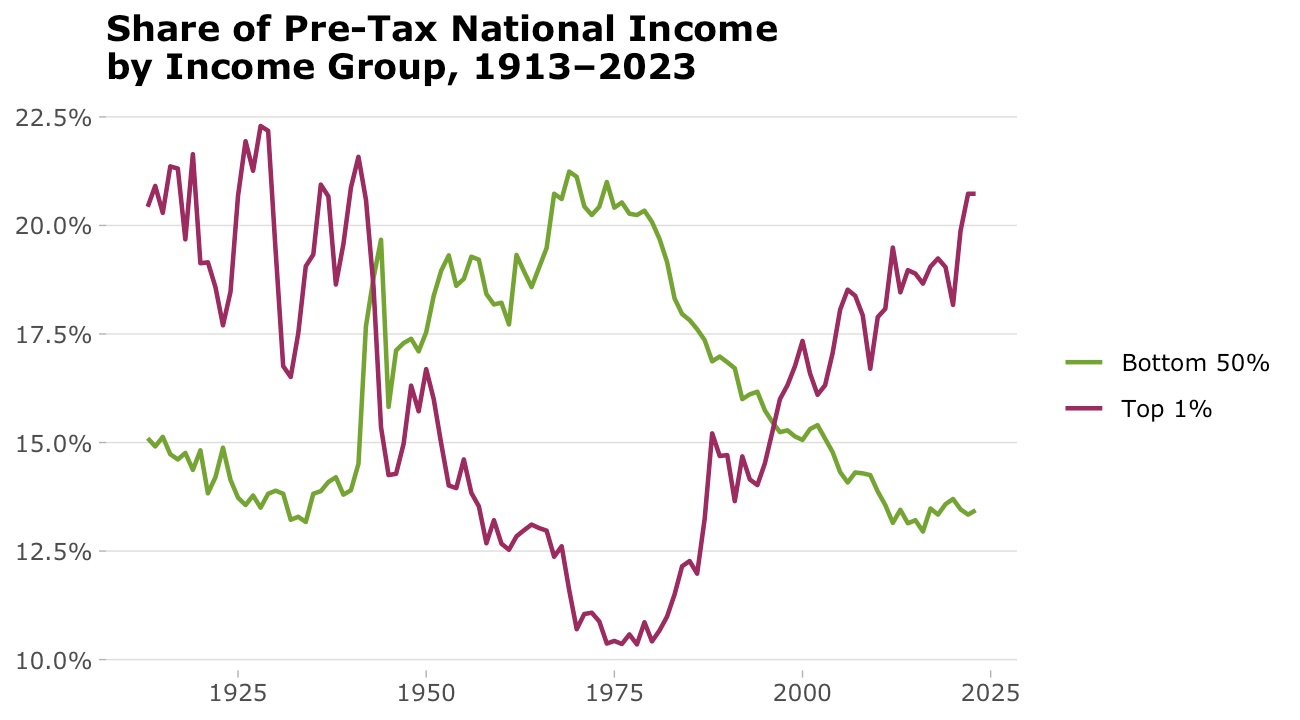

America’s highly unequal income distribution makes cost shocks more common and its economy more fragile. As income inequality has widened, the share of consumption spending by wealthy households has grown: Today the top 10 percent of American households earn 45 percent of pretax income, up from 30 percent in 1979, and represent approximately 50 percent of consumption. This makes the economy more recession-prone under negative shocks to top earners.

3) Tackle supply-side constraints to housing

Unique developments over the past decade create a pressing need and a unique opportunity to address the housing crisis through solutions that address supply- and consumer-side constraints.

In the 15 years since the Great Recession, housing has become increasingly unaffordable for families and an ever-growing drag on the US economy. Progressive economics was instrumental in addressing earlier housing crises—the US mortgage market is unique in the world and has been a ticket to the middle class for millions of families since being created in the 1930s. But as housing construction stagnated and never recovered from the 2007 housing crash, this most fundamental need has become increasingly undersupplied and both purchase prices and rents have risen much faster than overall inflation.

The best time to fix the housing crisis was decades ago, but the second best time is now. Progressives must bring a wide variety of solutions to the table, reflecting a commitment to solutions rather than dogma. Ned Resnikoff’s essay discusses how we can unleash housing supply through a broader conception of local control and an understanding that making it easier to build housing is a key pillar of fixing supply problems. In a growing nation, a diverse set of solutions is required—including housing finance, rental assistance, and policies to address the hangover of a decade of cheap borrowing that has amplified the cost of moving, upsizing, or downsizing for growing families and seniors.

Policy is increasingly oriented toward housing as an investment rather than as shelter. Policies to lower costs for renters and non-wealthy homebuyers will be even more crucial amid higher interest rates and another four years of federal policies tilted toward the wealthy.

4) Make taxes more progressive

In a world of higher interest rates, lowering costs requires funding the government via tax revenue.

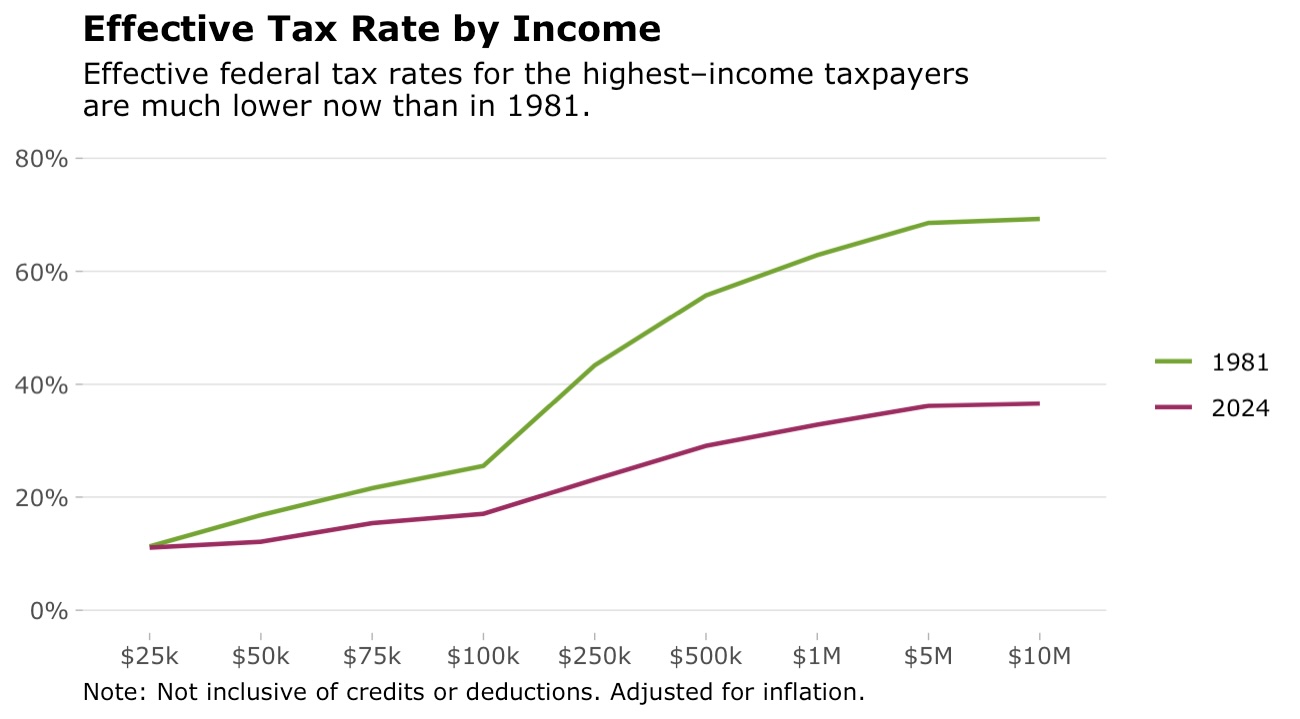

A full employment recovery implies higher interest rates as fewer resources go underutilized in the economy. Overall, higher interest rates mean higher borrowing costs, which make budget deficits more expensive and necessitate more tax revenue and a more progressive tax system. This makes public budgeting—and therefore efficient policies to accelerate economic recovery—all the more important.

The US is better positioned than any country in the world to make taxes more progressive—the next administration will see the 50-year anniversary of America’s failed supply-side tax cut experiment—in ways that will make the economy fairer and stronger overall. Two essays in the Restoring Democratic Growth section of this series explore taxation in more detail.

Essays on the Cost of Living

Breathing Room for All: Tackling the Cost-of-Living Crisis with Progressive Policy Solutions

By Elizabeth Pancotti and Alex Jacquez

Buffer Stocks and Better Futures: A Strategic Resilience Reserve to Reshape Market Stability

By Arnab Datta and Alex Turnbull

How to Fix Housing: The Pivot from Localism to Regionalism and Rule of Law

By Ned Resnikoff

The Safety Net

A truly democratic economy supports all the people under its jurisdiction. A safety net that works for everyone cannot operate through employment-provided benefits alone, nor while ignoring employment. With an aging population, supporting a dignified life for seniors is more important than ever. At the same time, America remains unique among advanced economies in failing to guarantee paid leave for working parents to support caregivers of Americans of all ages. And without some form of guaranteed cash assistance, American families lack resources to confront unforeseen shocks, such as the displacement new technologies can bring, as Block and Miller’s essay described above.

Like many financial crises, these risks can remain invisible while everything holds together for a time—but the shortfalls in America’s safety net now must rise to the level of macroeconomic policy concern. The population needing care is expected to increase by millions as our society ages over the next 20 years. This can either be a drag on the economy or an enormous opportunity.

1) Defend and expand public forms of retirement and health assistance

We’ve created less equitable, less secure retirement and made the entire economy more vulnerable in the process. Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid are the backbone of financial security for today’s retirees and future generations.

From housing to health care to receiving benefits earned over a lifetime of work, older Americans have to interact with complex systems of a submerged state, which puts them at outsized risk of harm from predatory middlemen. Customer service at benefits agencies like Social Security is one of the last lines of defense ensuring seniors get the benefits they have earned, and, as America ages, now is the time to make benefits easier to access. A muscular state with the resources and capacity to simplify the numerous benefits seniors have earned is a key piece of ensuring a secure retirement. This requires high-quality public services, coupled with strong regulation of health care.

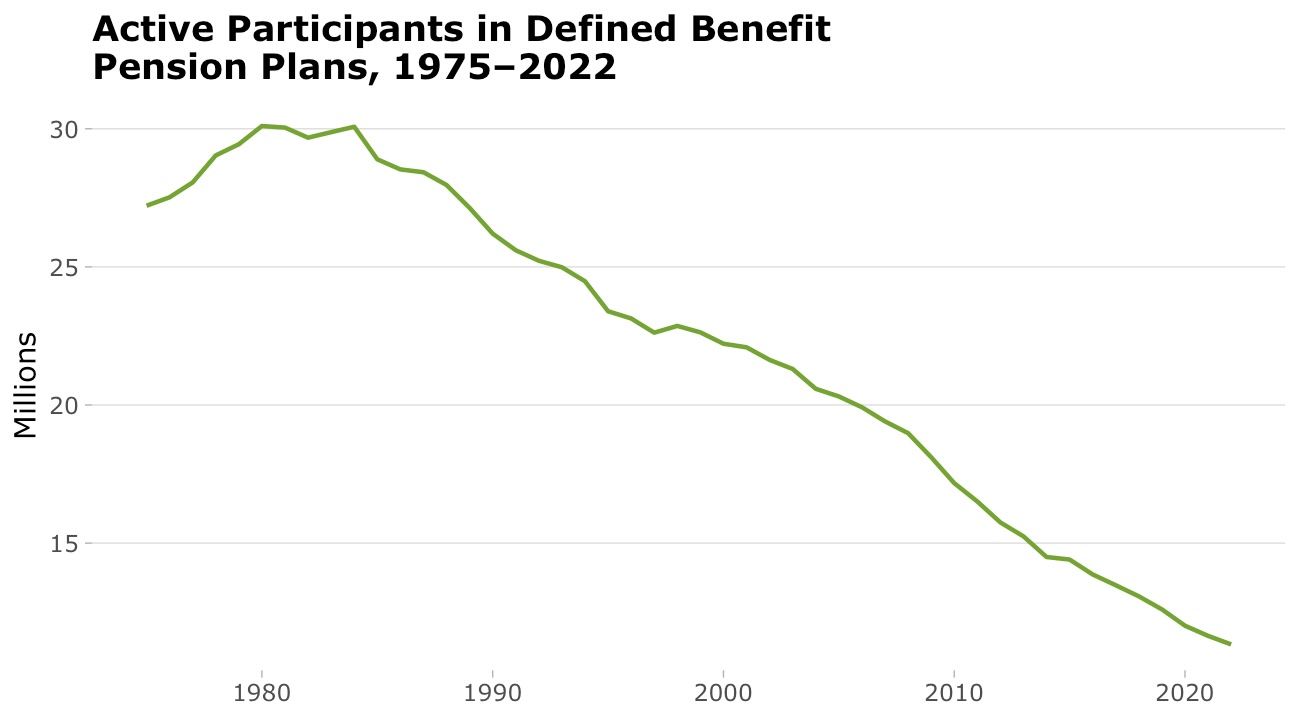

Since the 1980s, American workers in the private sector have almost universally lost access to the defined-benefit pension systems that once made secure retirement an expectation. The shift to less egalitarian retirement plans has not only cut many middle class families out of retirement benefits but left them more reliant on Social Security than ever. At the same time, it has allowed high-income families to amass increasingly large portfolios of tax-free assets that lock inequality into future generations.

For future retirees, there is no time to waste, because the benefits of stronger reforms can compound for years. A public option for retirement accounts with lower costs and actuarial fairness across financial products would give millions of families access to a more secure retirement at essentially no cost. Expanding and shoring up Social Security, particularly for lower-income families who will rely on it for most retirement income, is an urgent goal that progressives must address, precisely because the kind of aspirational centrism presumed to make Social Security safe for the second half of this century has collapsed under today’s toxic politics.

2) Provide cash assistance programs

Cash assistance, as a supplement to a comprehensive safety net program, ensures households have the resources to confront unforeseen shocks.

Chaos must be avoided—but unpredictable shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic are impossible to fully prevent. To help Americans during such times of crisis, cash assistance can provide access to stability and safety. And a universal program that every American can access ensures the equal distribution of resources and reduces onerous administrative burdens associated with means-tested programs.

In their essay, Michael A. Lewis and Eri Noguchi explore one way we might foster security by analyzing the challenges and promise of implementing a universal minimum income for all Americans. Seeing it as the “floor” that can even the playing field for everyone, they compare it to more targeted benefit programs and assess the political feasibility of this increasingly popular idea to shore up other safety net programs with cash, no strings attached.

3) Implement diverse solutions to the care crisis, including a public option for caregiving

Care policy need not be uniform to improve dignity for caregivers and Americans who need care alike.

Care is already a large and growing source of jobs in America. Furthermore, the care economy is dramatically larger than captured in GDP, precisely because so much of the work is informal. This informal nature is an opportunity for policymakers to support caregivers and unlock economic growth. Whether it’s parents who have to work no matter how tired or sick they are from a night caring for a sick toddler or adults caring for an ailing parent who haven’t had a day off in years, the productivity drag of informal caregiving on the formal economy is real—and affects earnings and retirement prospects for future generations. Supporting caregivers is good for business, good for families, and good for the economy—especially when care work comes out of the shadows and into the formal economy.

Caregiving in America can be isolating because the challenges are so acute, but, precisely because caregiving strains are so common, addressing this issue produces profound benefits. For Federal Reserve chairs and treasury secretaries and beyond, the economic case for an improved care economy is clear. The perfect care system for all may not exist, but progressives have spent decades generating a rich set of policies that benefit children, parents, temporarily and permanently disabled Americans, and retirees. We need not limit ourselves to only one solution. A public option for care could provide vital assistance to families who cannot afford private care services, while still allowing for a private market with flexibility for those who need it.

Essay on the Safety Net