Restoring Democratic Growth

April 29, 2025

By Roosevelt staff

‘Restoring Democratic Growth’ is part of the 2025 Roosevelt essay collection: Restoring Economic Democracy: Progressive Ideas for Stability and Prosperity

In a 1936 Fireside Chat—quoted by Osita Nwanevu in the introduction to this collection—Franklin D. Roosevelt said, “Our needs are one in building an orderly economic democracy in which all can profit and in which all can be secure.” This means ensuring everyone has access to and a voice in our economy, as the other sections in this collection explore. But, as Roosevelt understood from the beginning, it must also mean driving public policies that unleash innovation and shared growth.

This section helps set the terms for that agenda, with essays on industrial policy, green energy, taxation, and competition policy. While these essays don’t cover every dimension of a growing economy—for example, trade and international relations are absent—they converge on an overarching principle: The federal government can and must drive growth toward specific ends, most immediately a greener and more inclusive future.

For most of the 2010s, progressives targeted those goals in the context of a stagnating economy. The long, slow recovery from the Great Recession led to a decade of work by economists and policymakers focused on how to stimulate the economy and job creation essential for shared prosperity. We saw the fruits of this work in the remarkable rebound from the COVID-19 recession—and quickly learned its limits too.

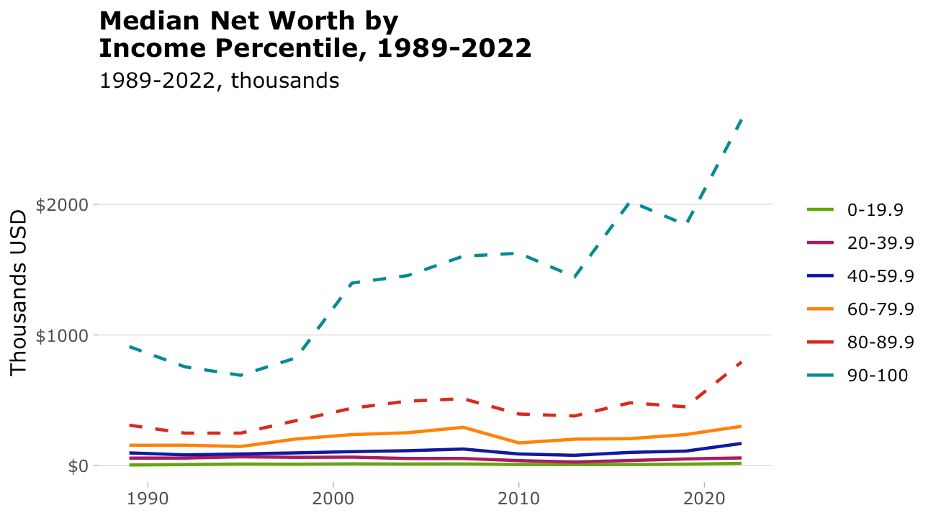

After overseeing the fastest economic recovery in decades, the Biden administration maintained a period of rapid growth driven in part by legislation that encouraged investment in industries the United States badly needed, including green energy and microchip manufacturing. During this time, we also saw politically devastating rates of inflation and continued concerns about extreme inequality. Further, even as the economy boomed according to standard measures, most individuals have not yet seen the direct results of investments, which may take years to be visible.

Could this have looked different, and how? Could slightly different approaches or conditions have allowed investments to drive a popular and more democratic full-employment economy? More importantly, what lessons can we learn for the next progressive governing moment?

One way to approach this question is to consider which tools the Biden administration and Congress had at their disposal and which were effectively cut off by a combination of dysfunctional politics, the legacy of 40 years of neoliberal policies, and/or the courts. Chief among these missing tools: a robust labor movement and the ability to do real tax reform.

The policymakers behind our era of industrial policy have consciously taken World War II mobilization as its inspiration, but that mobilization relied on a three-part governance structure: business, government, and labor. For example, organized labor helped keep wages and prices from an inflationary spiral because they were consulted about policies to manage the economy. Over the past four years, with private-sector union density hovering below 7 percent, labor has not held a truly equal seat at the table. This left the Biden administration handing out incentives and rewards to corporations through industrial policies at the same time it was trying to constrain excess corporate power through its administrative antitrust authorities. As Elizabeth Wilkins argues in her essay, resolving this seeming contradiction is a necessary goal for progressives going forward. Doing so will be substantially easier with a more robust role for the labor movement.

World War II precedent also offers insight into how taxes should play a more active role in industrial policy. During World War II, Roosevelt was clear that he wanted to prevent the creation of “war millionaires,” businessmen profiting from the country’s reliance on their companies. Congress thus raised taxes both with the general goal of keeping inflation in check through reduced demand, and in more targeted ways—for example through an excess profits tax meant to address wartime profiteering. This kind of active use of taxes to help shape the structure of the economy through more than incentives was also largely foreclosed over the last four years. Decades of neoliberal hegemony have limited the ability of politicians on both sides of the aisle to describe and view taxation as good for the economy.

The economic growth of the last four years was a remarkable achievement especially when we consider the limited set of tools available to the Biden administration. Nevertheless, those limits were real and had political and economic consequences. Compromises during the legislative process meant that Biden-era industrial policy ultimately did not include the care-focused provisions of the original Build Back Better legislation, meaning that sectors dominated by women and especially Black, Indigenous, and women of color experienced far fewer benefits from new legislation than disproportionately male manufacturing industries. Going forward, a true progressive vision for long-term economic growth will require investments not just in manufacturing but in service sector jobs.

Over the long term, economic growth requires stability. And democratic stability requires a robust and functioning set of institutions—from a legislature that can pass ambitious legislation (including taxes that raise revenue and limit excess concentration of wealth) on a bipartisan basis, to labor unions that can represent workers through the implementation of such legislation, to administrative agencies that can act efficiently to serve the people. The essays in this section explore what growth-forward progressive public policies could look like under that institutional configuration. They argue for policies that achieve dual goals: growing the industries and infrastructure we need and reshaping power in the economy through government investment, regulation, and taxation

Industrial Policy

Across the Trump and Biden administrations, one common thread has emerged: Each believes we need more aggressive tools to solve the crises at hand, even if they radically disagree about what those crises are and what tools are appropriate. President Trump and his allies look for muscularity in an unchecked executive that can pursue an agenda of building power for themselves, punishing their enemies, and expanding America’s territorial boundaries. Progressives are looking to streamline bureaucratic processes without losing fundamental democratic checks so that the government can drive an efficient build-out of sustainable infrastructure and curb outsized corporate power in stronger ways. The shared desire for a more forceful federal government helps clarify the stakes of a clear progressive vision of industrial policy—one that shows that public institutions can move with resolve and democratic values to address crises.

Progressive industrial policy will be defined both by what it is applied to and, just as importantly, by how it is applied. In the following essays, Mariana Mazzucato and Costa Samaras make the case that industrial policy must be trained on the existential threat of the climate crisis. But that is not where its application should stop. Industrial policy can and should help reshape critical industries in both the manufacturing and service sectors. Indeed, focusing too exclusively on manufacturing will leave vast sectors of the economy—those more likely to be dominated by women and people of color—out of this work.

Regardless of the industry to which it is applied, a few policy principles will be essential to ensure that we are engaging in a democratic form of industrial policy.

1) Set conditionalities that check corporate power and drive innovation

Ensure that industrial policy investments do not simply enrich powerful corporations and those with strong political connections. Funding must be conditional not only on what goods and services recipients offer but on how they are running their businesses.

Public funds should not be driving excess profiteering and the further financialization of the economy. Rather, investments must encourage future innovation that will serve the public. This requires that industrial policy investments include guardrails and conditions that look beyond the core industrial policy mission driving them and ensure that investments don’t unintentionally undermine other policy commitments, like checking corporate concentration. In “Multi-Solving, Trade-Offs, and Conditionalities in Industrial Policy,” Isabel Estevez argues, “Each policy influences existing power relations and distributional outcomes—who gets or loses access to clean air and water; who keeps or loses their homes, jobs, or livelihoods.” We should not pretend policies exist solely in the bubble of their own intentions. That said, taking seriously how policies interact with each other to advance or hinder a whole policy agenda also requires acknowledging when a conditionality might undermine or weaken a core policy’s ability to move its mission forward. There is no hard and fast rule about the right number of conditionalities to attach to a policy. Instead, policymakers must always be considering what parameters and conditions on investments are required to ensure that they drive the kind of economy we want to see.

2) Engage labor

Give labor a seat at the table in setting industrial policies. For that to happen, industrial policies must be deployed to grow the labor movement.

The tripartite governance structure essential to a muscular yet democratic industrial policy will not be possible without growing the labor movement. Growing the labor movement will require new laws to enable organizing, but industrial policies can play an important supporting role. Industrial policies that can help grow the labor movement include an insistence that federal funds be conditional on project labor, and prevailing wage agreements that lay the groundwork for fair bargaining by setting a floor that employers and workers agree on ahead of time. Further, a whole-of-government approach to promoting labor organizing rights should be deployed alongside industrial policies. For example, the National Labor Relations Board must use its rulemaking power to make existing labor law work for workers in a 21st century economy. For another example, antitrust agencies must prioritize enforcement against employer policies that limit worker agency, such as noncompetes and wage-fixing.

3) Build state capacity

Craft industrial policies to build and reflect increased democratic state capacity. The state must be able to show “a clear link between industrial policy and improvements in people’s lives.”

When progressives next have a chance to implement industrial policies, it will not be with the administrative state of 2024. The sustained and unprecedented attack on public institutions that we have seen in early 2025 means that rebuilding state capacity will be an important part of the job. To effectively drive the kinds of industrial policies required over the long term, the rebuilt state will need to have new abilities and functions including: a willingness to take risks that foster innovation, strong mechanisms for sharing the rewards broadly when risks pay off, and processes that streamline delivery times without abandoning democratic oversight. What exactly those processes will look like requires research and experimentation, but the best hypothesis to date is that structured public input and review early in the policymaking process can help avoid lengthy litigation down the line while still ensuring accountability.ding: a willingness to take risks that foster innovation, strong mechanisms for sharing the rewards broadly when risks pay off, and processes that streamline delivery times without abandoning democratic oversight. What exactly those processes will look like requires research and experimentation, but the best hypothesis to date is that structured public input and review early in the policymaking process can help avoid lengthy litigation down the line while still ensuring accountability.

Competition

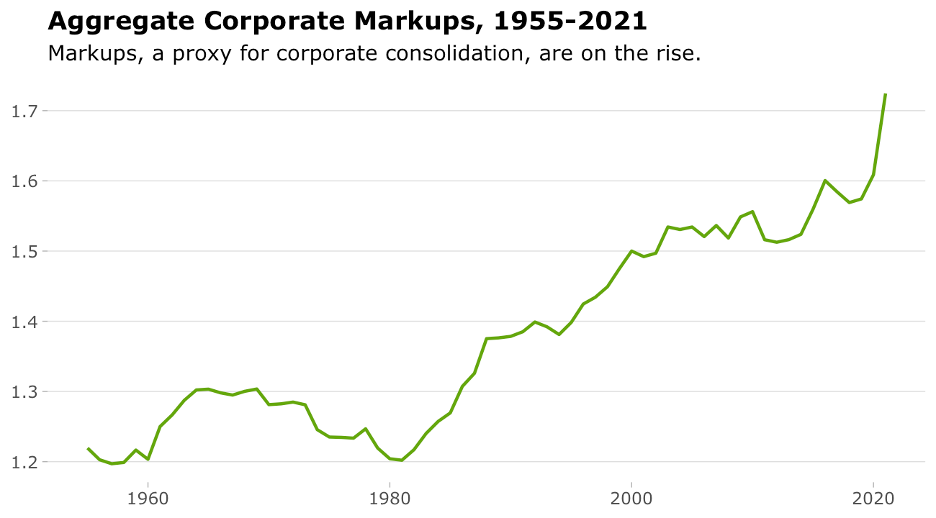

During the Biden administration, we saw members of the relatively new Neo-Brandeisian movement join the highest ranks of government to steer a new approach to competition policy that moved beyond the consumer welfare standard. At the antitrust agencies, these leaders pushed back on outsized corporate power not just for its effects on prices but for its harms to worker power, small businesses viability, and democracy itself. At the same time, policymakers took a hard look at common corporate practices that funnel money away from innovation and into shareholders’ pockets.

That was an important start, but as we are seeing every day, outsized corporate power continues to pose grave threats to our democracy.

In the following essays, Elizabeth Wilkins and Lenore Palladino explore how we can better take on corporate concentration across government to ensure more widespread prosperity and build true countervailing power to large corporations and the obscenely wealthy men who run them.

1) Deploy a competition and competitive process test

Continue to move antitrust enforcement away from the consumer welfare standard.

For almost half a century, regulators had used the consumer welfare standard as the primary basis for assessing corporate concentration. They defined “sound competition” by prices alone, affording them a short-term and narrow view of consumer health. Under the last administration, regulatory agencies deployed a new approach, taking a more comprehensive view and thinking of potential mergers and acquisitions through the lens of how they could affect the “competitive process.” As Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter explained, “The heart of the competitive process is the guarantee that everyone participating in the open market—consumers, farmers, workers, or anyone else—has the free opportunity to select among alternative offers.” This shift in focus is similar to the one proposed in a 2018 Roosevelt report by Marshall Steinbaum and Maurice E. Stucke, who offered four key goals for antitrust enforcement:

- Protect individuals, purchasers, consumers, and producers

- Preserve opportunities for competitors

- Promote individual autonomy and well-being

- Disperse and deconcentrate private power

This more holistic approach to examining corporate concentration must continue to be our guiding principle. Further additions might also be included. For instance, based on new research about how innovation happens, Ketan Ahuja has proposed that antitrust regulators focus on how the broader ecosystem is organized to create innovation capabilities.

At the same time, we cannot underestimate the importance of prices to consumers. An effective competition standard must be paired with policy approaches (discussed in pieces by Elizabeth Pancotti and Alex Jacquez as well as Arnab Datta and Alex Turnbull earlier in this collection) throughout the government to address costs.

2) Deploy a whole-of-government approach to competition policy

Apply existing authorities across government to address excessive corporate concentration.

The antitrust enforcement agencies are not the only parts of government that should take a renewed look at competition policy. As Elizabeth Wilkins writes in her essay, corporate concentration’s effects extend far beyond what consumers pay for consumables, to what workers earn and how we all access essential goods and services, from health care to housing to energy. Researchers should further explore how agencies across government could apply an effective competition standard to further their mandate.

3) Ban anticompetitive and anti-innovative practices

Demand legislation and rulemaking that encourages corporations to invest in innovation more than self-enrichment.

Lax antitrust enforcement is not the only reason corporate power has consolidated over the past half-century. As Lenore Palladino and William Lazonick have argued, in the 1980s the SEC dramatically changed its approach to regulating corporate stock price manipulation and began allowing companies to manipulate stock prices that pulled money out of innovation and worker pay. In 2022, Congress imposed a tax on stock buybacks, but an outright ban is still on the table. Further, we must do more to restructure markets to encourage innovation including, as Ahuja argues, banning noncompetes and encouraging nonexclusive licensing. Truly democratic growth requires laws and regulations that encourage companies to both innovate and share the fruits of that work widely.

4) Design a more democratic corporate oversight infrastructure

Give working people a voice in the process of corporate policymaking. Corporate oversight can be the realm of lawyers and technocrats, but its importance to all people demands their experiences inform government actions.

A whole-of-government approach to competition policy must be accompanied by an opening up of government to create more pathways for worker and consumer voice in competition policy decisions. As Wilkins writes, “Democratization of our market governance mechanisms —and our policy development process—is crucial to ensuring that they serve the entire public and that the public sees itself in those democratic outcomes.” This might mean creating more open meetings and meaningful comment periods, but we also need creative thinking about new forms of democratic access. What new technologies or institutional formations could be built to bring people into processes in ways that do not overly inhibit the government action that is necessary for growth?

Likewise, as Palladino argues in her essay in this collection, we should require corporate boards to be accountable to more than just shareholders. We can do this by legislating that fiduciary duty runs to all stakeholders—not just shareholders—and requiring workers and other stakeholders to have seats on corporate boards.

Taxes

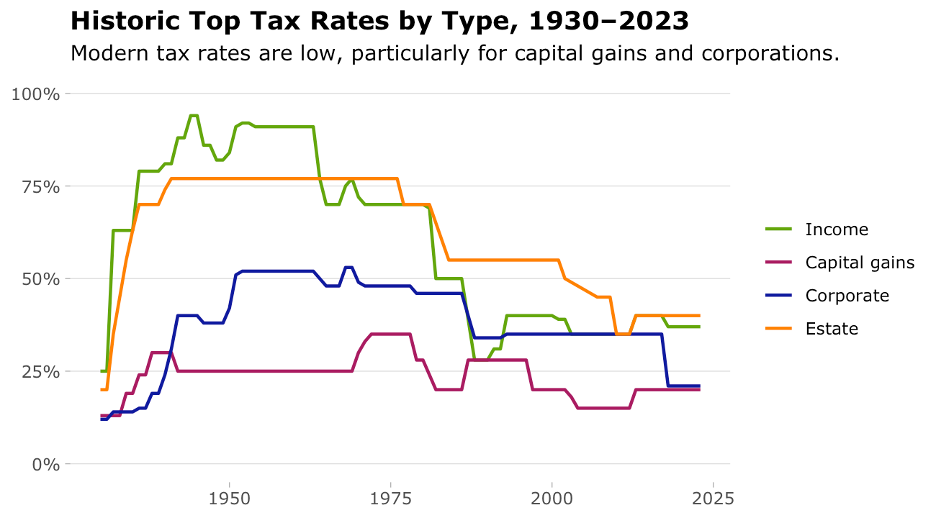

At least since Ronald Reagan’s rise to power, the American public has been sold the idea that taxation hinders economic growth. Politicians have argued that tax cuts for corporations and wealthy individuals would kick-start shared prosperity even as tax revenues took a nosedive and inequality soared.

In fact, a well-designed tax code is essential to an economy that grows democratically. As policymakers consider tax reforms—both related to the expiration of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act this year and in the long term—they should prioritize decreasing inefficiency and distortions throughout our economy, reducing economic inequalities, and raising revenues for public investments.

Policymakers on both sides of the aisle must recognize that taxes are neither the enemy of growth nor a necessary evil, but rather one of the basic tools with which we structure our economy. In the following essays, Chye-Ching Huang and Beverly Moran explore how we can use our tax code to build the economy we want: one that is both more equitable and more stable.

1) Design a tax code that minimizes and corrects societal ills and distortions

Use tax reforms to discourage activities that hurt the economy and our society and structure markets for shared prosperity.

Our existing tax system encourages unproductive behavior, such as speculation and rent seeking, which drives up inequality and hinders growth. Tax reforms that instead discourage activities that generate negative externalities will increase efficiency. The tax system can be a particularly effective mechanism for curbing negative externalities like pollution and speculation, improving the efficiency and stability of the economy even before the benefits of increased revenue are realized.

2) Make the tax code an essential tool for decreasing inequality

Ensure that corporations and the wealthy pay their fair share and mobilize the tax code to address persistent inequalities.

Tax reforms can achieve two goals in tandem: discouraging behaviors that increase inequality (such as generational wealth transfers) and raising revenue from our nation’s wealthiest to invest in programs that serve working families. This requires higher corporate and income tax rates, as Huang argues. We should also explore a wealth tax.

Further, where tax policies harm those at the bottom (such as carbon taxes that may reduce employment in the fossil fuel industry), we should use revenues raised to make the harmed whole (for example, through workforce development policies for displaced workers).

We should also be attentive to the way tax structures reinforce longstanding income, race, and gender inequalities. As a result of the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the wealthiest 1 percent of taxpayers enjoy a larger tax cut in a single day ($131) from the TCJA than the poorest 20 percent families get in an entire year ($90). Thinking through how tax cuts intersect with existing inequalities to exacerbate their effects is essential. For example, we should revisit long-standing policies like joint filing for married couples, which discourages women from working; the home mortgage interest deduction, which reinforces the racial wealth gap; and, as Beverly Moran argues in her essay, itemized deductions, which largely redound to the already wealthy.

3) Raise the revenue we need for a 21st century state

Bring tax revenue as a share of GDP much closer to our peer countries—which have an average tax-GDP ratio of 34 percent, compared to the US’s current 25.2 percent.

Federal revenue is essential for public investments and programs that help our economy grow and ensure it does so equitably. Yet the United States is a famously low-tax country, and repeated tax cuts of the last half-century—including those in 2017—are a big reason why. The result is that federal spending is lower and federal borrowing is higher than most other peer countries. We need to push up the revenue our tax code raises, and there is lots of space to do it in a tax code that encourages shared growth instead of profiteering.

4) Don’t use the tax code as a substitute for true public programs

Reach more people more efficiently through direct spending. We should not limit ourselves to administering all government support and services through the tax code.

The tax code is critical architecture for our economy, but politics—and in particular an increasingly deadlocked Congress—have left us reliant on it for any expansion to our social safety net. We should use the tax code to address economic inequality, but we should not rely on tax credits where we need true public programs. A child care tax credit, for example, will not sufficiently address our childcare crisis. For that we need public investments in childcare. The revenue we raise from an effective, progressive tax code must fund investments in robust public programs that create the democratic economy and society we deserve.