Restoring Economic Democracy: Progressive Ideas for Stability and Prosperity

April 29, 2025

Foreword

by Elizabeth Wilkins, President and CEO, Roosevelt Institute

For decades, the American people have expressed deep frustration with the economy as it is, and with what it has failed to offer us: Economic security, defined not just as the ability to make ends meet, which too many cannot, but as a foundation that allows us to live the lives we want. Agency in the most important economic choices of our lives, from where to live, to when we can start a family or business, to how we can care for our loved ones. Power in our workplace and in our politics.

Fueled by that frustration, many have lost faith in our institutions and in democracy as a system—a vacuum that authoritarian forces are always willing to fill.

Our vital task in the coming years is to prove that democracy can deliver, better and more quickly than any alternative. We must renew and create institutions that empower people and ensure the material conditions they need to participate meaningfully in politics. We must show people that government is willing to take on powerful interests standing in their way and exploiting them. We must make people feel seen and heard and part of something bigger than ourselves.

In this moment, we’re seeing the opposite. Private interests and unelected billionaires are tearing down our public institutions and leaving terror and pain in their wake. Far from the economic security people wanted, chaos and instability have defined these early months of Donald Trump’s second administration, with essential pillars of our social contract in the crosshairs. Many in civil society—from unions to fired government workers to lawyers—are doing vital frontline work to mitigate the fallout and slow the backsliding of our political system.

At the same time, we must also plan for what comes next. That plan cannot be to go back to what we had before—the hollowed-out institutions and painfully unequal society that sowed the seeds of disillusionment we now reap. We must think bigger about what our democracy and economy can look like. How we support people’s economic security and visions for the good life. How we expand the agency and power of families and communities. How we make our institutions more ambitious, nimbler, and more creative in curbing corporate power and strengthening workers’ hand.

That’s what this essay collection starts to do, bringing together great minds from a range of disciplines but united in their willingness to question the way things have been done, imagine something new, and point the way forward to a more robust democracy. Our contributing authors don’t agree on everything, and that’s part of the point: Now is the time to cast a wide net for ideas and build a big tent for the movement.

Together, these essays start to analyze the challenges we face today, learn from the wins of the last four years, and contemplate where we could have been bolder. They examine what the Trump administration’s policies are now undoing and imagine how democracy can better deliver the economy Americans need and want. They take today’s important conversations to new places. And most importantly, they remind us that there’s no such thing as “too ambitious” when it comes to fighting for workers and families.

Introduction

by Roosevelt staff

“The people are what matter to government . . . A government should aim to give all the people under its jurisdiction the best possible life.”

– Frances Perkins, US Secretary of Labor (1933–1945) and key architect of the New Deal 1

As we publish this collection of essays in the spring of 2025, the second Trump administration’s policies have hurled our economy and government into chaos.

Arbitrary, sweeping tariffs led to a $10 trillion global equity wipeout in a single week, a market meltdown that will live in “infamy.”2 The administration refused to quell fears of a recession, insisting Americans simply put up with “turbulence.”3 Legal residents have faced deportations off the street from masked, unidentified individuals.4 Thousands of civil servants and government contractors lost their jobs serving the public, only for a handful to be reinstated days later, all in the name of government efficiency.5 Meanwhile, the so-called Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) claimed its cuts to government contracts saved American taxpayers billions, only to realize they had “confused billions with millions, triple-counted the same cancellation, or claimed credit for contracts that had ended years or even decades before.”6 What exactly they have accomplished is still unclear—though we do know that DOGE’s current leader, unelected billionaire Elon Musk, will reap more of the very government contracts he claims he wants to eliminate.7

This is, astonishingly, only a fraction of what has happened in federal policy since January 20.8 To call it a crisis seems an understatement.

So why publish a collection of progressive policy visions now? In times of crisis, are ambitious thinking and nitty-gritty ideas about economic democracy really what we need? The architects of the original New Deal would tell us yes.

In the early 1930s, deep economic depression, rising global authoritarianism, and environmental disaster led many to question the foundations of democracy itself. Historian Ira Katznelson has described it as a time of “uncommon uncertainty,” where widespread fear arose not just from clear dangers, but from the inability of the average American to know what might happen next.9 It was in that moment of chaos that the first Franklin D. Roosevelt administration offered alternative visions for the future, visions that ultimately formed the New Deal.

Importantly, there was no one single remedy to solve all of America’s problems. Because the architects of the New Deal “possessed no fixed or sure policy approaches or remedies for the domestic and global crises of the day, they could consider a very wide repertoire.”10 Nor did they solve the problems of American democracy overnight. As Katznelson details, the FDR administration drew on expertise from across sectors, and spent years experimenting, debating, and designing a better, more responsible American state. These experts often disagreed with one another about macro and micro policy details, but they shared a common goal: a stable, predictable American government that served the interests of the many, not the few.

At the Roosevelt Institute, we are rooted in this legacy, in the FDR administration’s ambitious responses to the vast crises and inequities of their time. That history teaches us that chaos is a policy choice, and that the best remedy for chaos is bold and diverse ideas—to create democratic institutions that deliver for people, and shape the innovative and inclusive economy we need. That history also teaches us that transformation takes time and compromise, and is too often limited by the prejudices of our era. But this knowledge must not lead us to narrow our vision or stall on action. It is precisely in moments like this when we need to gather better visions for our democracy.

The contributors to this collection come from government, academia, unions, advocacy, and journalism. Some of them helped usher in positive changes from within previous administrations, and have learned firsthand how difficult systemic, long-term change can be—but they have also learned what works, and what is still required to craft a state that is both ambitious and practical in addressing people’s greatest needs and aspirations. Others have studied policy design from outside the government, and offer new ways of thinking about thorny policy problems. Bringing these contrasting thinkers together in one document shows the great range of what is possible when we learn from and debate with one another.

We open this collection with essays from journalist Osita Nwanevu and Senator Chris Murphy. Nwanevu explores the concept of “economic democracy,” an idea that FDR championed. This idea holds economic empowerment as deeply intertwined with democratic freedom. “Democracy isn’t an ideal the American people should be weighing against their economic well-being,” Nwanevu argues. “It’s an ideal that can economically empower them.” Senator Murphy explores restoring the promise of economic opportunity beyond the ever-shrinking circle of communities, occupations, and individuals who enjoy it today. The rest of the collection is divided into three sections, representing core goals that unite the essay writers across policy platforms: Democratic Economy, Democratic Growth, and Democratic Institutions. These essays grapple with the high cost of living, the housing crisis, the growing influence of AI, and the continued need to check growing corporate power. They offer a close look at the problems we must solve if we are to rebuild a thriving economic and political democracy. And they begin to explore policy solutions for a more racially equitable tax code, a greener industrial policy, dearly needed judicial reforms, and more.

These essays do not represent the totality of the problems we face or the progressive ideas to fix them, of course. Nor do each of these authors necessarily agree with one another on the best path forward. Indeed, we think disagreement is helpful—bold ideas that make us question basic assumptions can be most helpful in times like these. This is the beginning of the conversation: a collection to inspire and guide us, and to spark more conversations, more debate, and more study. Better visions for our democracy exist. The fight might be long and see setbacks, but we won’t compromise our vision for what the American people deserve: a government that aims to give every single one of them “the best possible life.”

Acknowledgments:

Elizabeth Wilkins, Hannah Groch-Begley, Suzanne Kahn, Michael Madowitz, Bilal Baydoun, and Matt Hughes all contributed writing for this collection. Thank you to our external essay contributors, whose author bios can be found here. Thank you also to Roosevelt staff and others who made this project possible: Aastha Uprety, Katherine De Chant, Noa Rosinplotz, Ira Regmi, Sunny Malhotra, Oskar Dye-Furstenberg, Todd N. Tucker, Emily Carew, Keesa McKoy, Alan Barber, DeDe Dunevant, Ariela Weinberger, Meredith MacKenzie de Silva, Djevna Neptune, Rachelle Klapheke, and Claire Greilich. Any errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies are the authors’ alone.

Note: The views expressed herein are solely those of the author of each essay, and should not be attributed to their employers—past or present. Nor should the views of any author of an essay herein be taken as endorsement of any other essay.

Read Footnotes

- Leah W. Sprague, “Frances Perkins: The Woman behind the New Deal,” Living New Deal, December 6, 2017, https://livingnewdeal.org/frances-perkins-woman-behind-new-deal. ↩︎

- Jeff John Roberts, “10 Days and a $10 Trillion Market Swing: How Trump’s Tariffs Changed the Global Economy, and What Comes Next,” Fortune, April 12, 2025, https://fortune.com/2025/04/12/trump-tariffs-stocks-bonds-supply-chain-what-comes-next. ↩︎

- Luke Broadwater, Colby Smith, and Ana Swanson,“ Trump Declines to Rule Out Recession as Tariffs Begin to Bite,” New York Times, March 9, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/09/us/politics/trump-recession-lutnick.html; Tim Hanrahan, “Trump Declines to Rule Out Recession,” Wall Street Journal, March 9, 2025, https://www.wsj.com/economy/trump-declines-to-rule-out-recession-45a1513f. ↩︎

- Devlin Barrett, Annie Correal, and William K. Rashbaum, “White House Denies Violating Judge’s Order in Deporting Venezuelans,” New York Times, March 16, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/16/us/politics/trump-venezuelans-deportations-el-salvador.html; Jake Offenhartz, Kathy McCormack, and Michael Casey, “Turkish Student at Tufts University Detained, Video Shows Masked People Handcuffing Her,” Associated Press, March 26, 2025, https://apnews.com/article/tufts-student-detained-massachusetts-immigration-6c3978da98a8d0f39ab311e092ffd892. ↩︎

- Christina Jewett, “FDA Reinstates Fired Medical Device, Food and Legal Staffers,” New York Times, February 24, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/02/24/science/fda-safety-workers-reinstated.html. ↩︎

- David A. Fahrenthold, Emily Badger, and Jeremy Singer-Vine, “Struggling With Errors, DOGE Deletes Billions More From List of Savings,” New York Times, March 3, 2025,

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/03/03/us/politics/doge-musk-contracts-wall.html. ↩︎ - Tim Balk, “The US Awarded Large Space Contracts to Companies Owned by Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos,” New York Times, April 4, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/live/2025/04/05/us/trump-news-tariffs/the-us-awarded-large-space-contracts-to-companies-owned-by-elon-musk-and-jeff-bezos. ↩︎

- Karen Yourish, Eric Rabinowitz, Ashley Wu, Lazaro Gamio, Aishvarya Kavi, and Minho Kim, “All of the Trump Administration’s Major Moves in the First 87 Days,” New York Times, last accessed April 18, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/us/trump-agenda-2025.html. ↩︎

- Ira Katznelson, Fear Itself: The New Deal and the Origins of Our Time, (Liveright, 2013), 33. ↩︎

- Katznelson, Fear Itself, 34. ↩︎

Table of Contents

Framing the Conversation

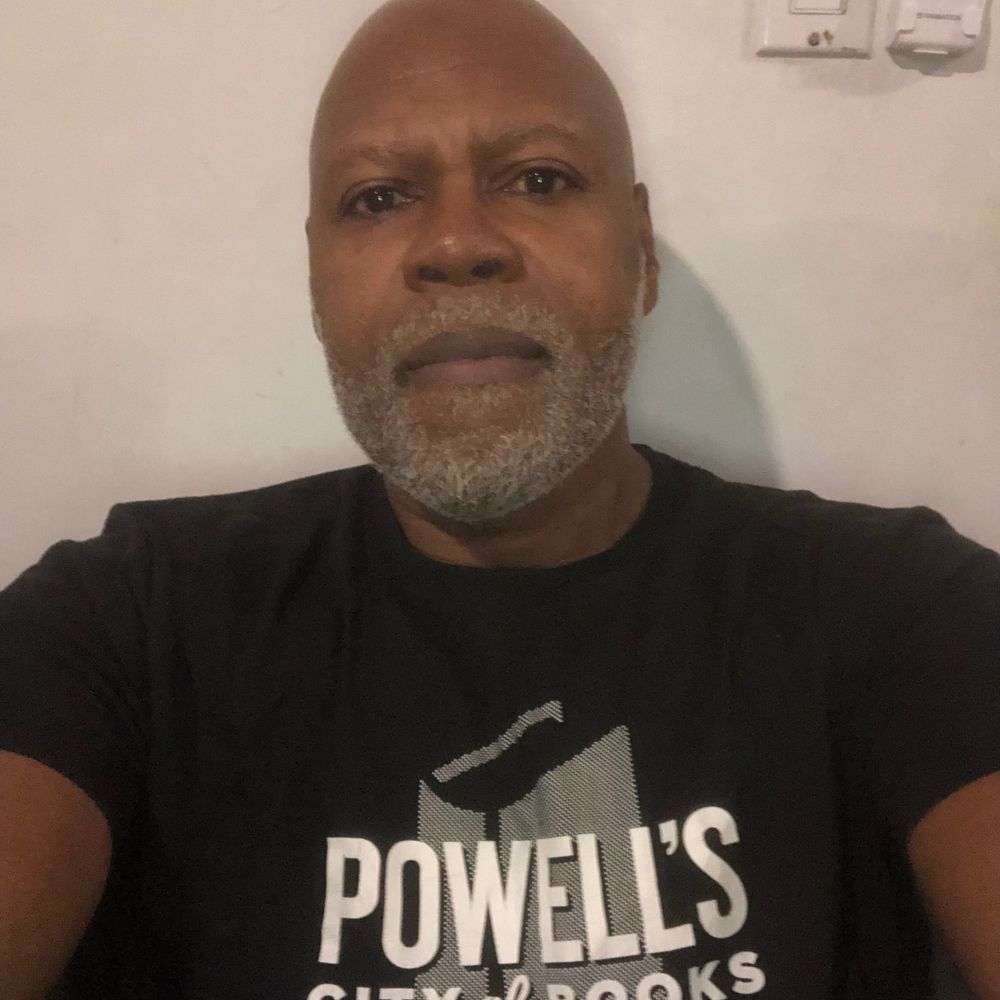

- Osita Nwanevu: By the Workers, for the Workers: Building Economic Democracy

- Sen. Chris Murphy: A Good Life Starts in a Good Hometown

Restoring a Democratic Economy

Restoring Democratic Growth

Restoring Democratic Institutions