Policy Feedback in the Pandemic: Lessons from Three Key Policies

October 19, 2023

By Jamila Michener

The US government took extraordinary action to temper the economic fallout of COVID-19 by advancing pivotal policies. Once implemented, policy can alter people’s lives in ways that shape their attitudes, actions, and relationship to government. Such feedback can be a healthy part of democratic processes, making polities more responsive and adaptive.

The distinctive set of policies passed in the wake of COVID-19 raised expectations in the United States for this kind of feedback. Yet the fraught political paths of these policies, combined with the apparent absence of short-term positive feedback, also renewed questions of whether and how much policy really shapes politics.

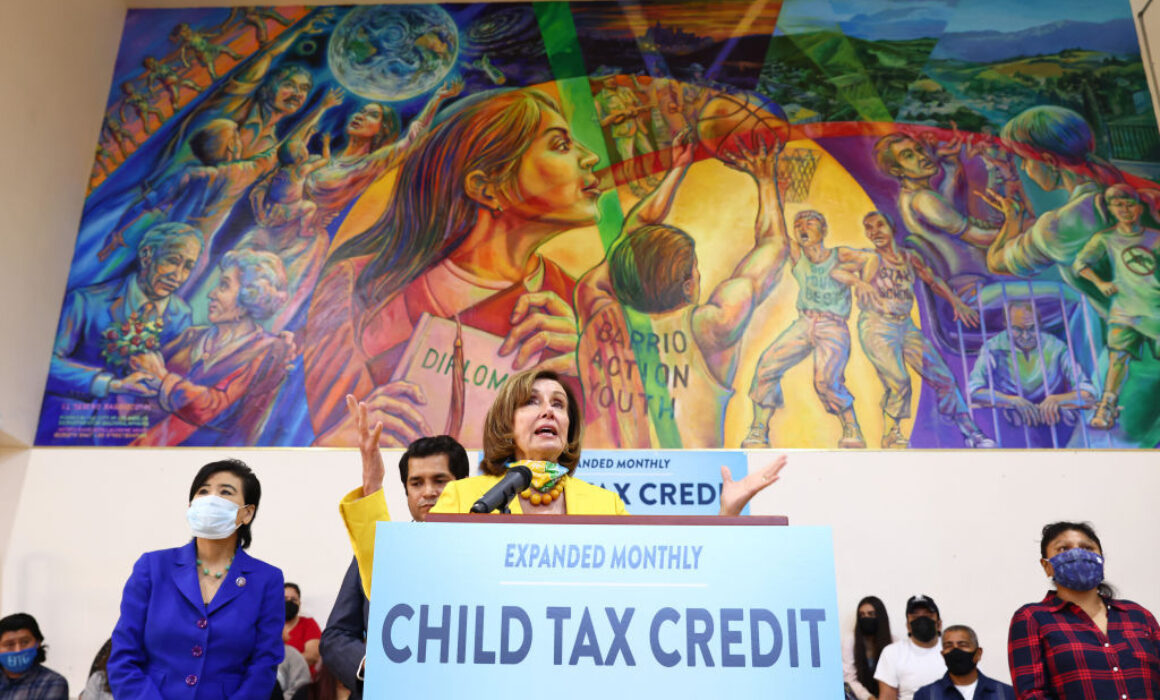

(Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images)

Introduction

COVID-19 wreaked financial havoc in the lives of lower- and middle-income Americans, and disproportionately so in Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities (Parker, Minkin, and Bennett 2020; Horowitz, Brown, and Minkin 2021; Kochhar and Sechopoulos 2022). Early in the pandemic, millions of people lost their jobs and millions more saw their hours or pay reduced (Bureau of Labor Statistics 2021; Cajner et al. 2020; Shelton 2021). This translated into staggering material hardship as increasing numbers of Americans reported not getting enough to eat, falling behind on rent, and struggling to cover basic living expenses (CBPP 2022). In response to such widespread deprivation, the US government took extensive action to temper the economic fallout of COVID-19. Three pivotal federal policies included (1) a historic expansion in the child tax credit; (2) billions of dollars in funding for emergency rental assistance; and (3) a prolonged pause in student loan debt payments and accrued interest followed by a (failed) proposal to enact partial relief of federal student loan debts. Born from the unique circumstances of the pandemic, each of these policies had rocky paths. Student debt relief was stopped in its tracks by a federal judge in North Texas who deemed it unlawful (Department of Education v. Brown 2023), and the program remained in limbo until the Supreme Court struck down the Biden administration’s student debt relief program in the June 2023 Biden v. Nebraska decision. The court ruled that the administration overstepped its authority when it moved to cancel hundreds of billions of dollars in student loans. Emergency rental assistance has not come under direct legal scrutiny, but the Supreme Court invalidated a nationwide moratorium on evictions just eight months after the first federal emergency rental assistance legislation was passed. This intensified the need and demand for assistance during a time when efforts to implement the program were already foundering. The expanded child tax credit was unaffected by the courts, but ran aground politically within one year, failing to receive sufficient support in Congress to make benefits permanent before their expiration.

Despite their travails, these policies had remarkable economic and social benefits. They also held promise for enduring shifts in American politics. Policy can shape citizens’ attitudes, actions, and relationship to government. Policies can also create enduring political institutions and capacities, generate new ideas or expectations, and change the horizon of what seems necessary or possible.

Despite their travails, these policies had remarkable economic and social benefits. They also held promise for enduring shifts in American politics. Policy can shape citizens’ attitudes, actions, and relationship to government. Policies can also create enduring political institutions and capacities, generate new ideas or expectations, and change the horizon of what seems necessary or possible.

Scholars refer to the political consequences of policy as policy feedback (Béland, Campbell, and Weaver 2022; Hertel-Fernandez 2020). The core insight of policy feedback theory is that “new policies create new politics” and that as this happens, “policies also remake politics” (Schattschneider 1935; Skocpol 1992). Under this formulation, policy is not just an output of the political process—it is also a crucial input that can structure future possibilities (Pierson 1993; Hertel-Fernandez 2020; Michener 2019). Scholars have found evidence of policy feedback for the GI bill, Social Security, cash assistance, Medicaid, after-school programs, criminal legal policy, immigration enforcement, housing policy, consumer finance, and more (Mettler 2005; Campbell 2003; Soss 2000; Michener 2018; Barnes 2020; Lerman and Weaver 2014; Rocha, Knoll, and Wrinkle 2015; Cruz Nichols, LeBrón, and Pedraza, 2018; Johnson, Meier, and Carroll 2018; SoRelle 2020; Thurston 2018).

The sweeping slate of policies passed in the wake of COVID-19 put a spotlight on policy feedback. Journalists, politicians, organizers, and academics openly contemplated the political consequences of pandemic policies. This was perhaps most striking for the expanded child tax credit (CTC). Aware that the CTC expansion had a one-year time horizon from the very start, supporters hoped that its concrete and significant benefits for a large part of the population would swiftly power its path to permanence. Policy feedback was the (implicit) theory at the heart of such aspirations. The core premise was that the expanded CTC would gain enough mass support to make abandoning it politically untenable. But after failed efforts to extend the CTC, pundits, critics, and even supporters became skeptical. The CTC was the dog that never barked. Journalists puzzled over “the $100 billion question” of how the CTC “failed to create its own constituency” (Lowrey 2022) and lamented the impossibly short time frame for CTC feedback effects to take hold (Klein 2022). The apparent absence of short-term CTC feedback cast a shadow of doubt on the effect of policy on politics. To some extent, this was warranted: Feedback loops are not automatic; they are systematically thwarted by political barriers, and they should not be seen as inevitable outcomes (Patashnik and Zelizer 2013; Jacobs and Mettler 2018). This is why scholars generally assess policy feedback through rigorous retrospective research. In the near term, however, there is also much to gain from a prospective approach: Even before the repercussions of a policy have fully played out, we can look to the political possibilities afoot given how that policy is designed and how it has started down the path of implementation. Forecasting the prospects of emergent feedback loops must be more than speculation: Instead, we can apply existing knowledge about policy feedback to analyze the ramifications of presently evolving policies. Hertel-Fernandez (2020) developed a checklist for progressive policy feedback loops that emphasized policy characteristics including visibility, traceability, and stigmatization; government capacity for implementation; the support of organized groups in cultivating positive feedback; and policy as a mechanism for deepening the inclusion of historically marginalized groups. Leveraging distinct lessons and observations emerging from the pandemic, this report draws on and extends Hertel-Fernandez’s baseline of considerations by underscoring two core elements of policy with implications for policy feedback:

- Characteristics of the target populations most affected by policy—that is, how such populations are socially constructed (i.e., understood in the public and political imaginary) and what power they can wield in political processes.

- Design and implementation features of policy, including timing/duration, delivery mechanisms, visibility, and the administrative burden created.

By taking these factors into account, organizers, advocates, and policymakers can identify opportunities to advance nascent policy gains by building power among racially and economically marginalized denizens, and transforming the horizon of ideas, perceptions, and policy possibilities that currently structure the US political-economic landscape.

Table 2. Policy Design and Implementation

Key Takeaways

This report emphasizes that democracy-enhancing policy feedback loops are more likely when:

- Civil society organizations intensively and strategically build power among the target populations most affected by policy and most crucial for altering existing power dynamics.

- Policymakers and civil society organizations develop and coordinate messaging and organizing strategies aimed at shifting policy discourse and public perceptions in ways that facilitate long-term wins.

- Policymakers and policy advocates design feedback-sensitive policy featuring at least four key elements: (1) longer durations of policy benefits; (2) immediate benefit without lags; (3) centralized and streamlined policy delivery; and (4) minimal administrative burden.

- Civil society organizations and policymakers render the government’s role in providing economic relief as visible as possible for as long as possible, particularly to the populations most vulnerable in the face of existing political-economic configurations, whose inclusion in political processes is most vital.

Related Resources

Why This Matters: Policy Feedback in the Pandemic: Lessons from Three Key Policies

Read the blog post Opens in new windowHow Policymakers Can Craft Measures That Endure and Build Political Power

Read the paper Opens in new windowUnderstanding the Effects of Windfalls: What People Do with Financial Payouts, and What It Means for Policy

Read the report Opens in new windowA True New Deal: Building an Inclusive Economy in the COVID-19 Era

Read the report Opens in new windowAuthor

Jamila Michener

Jamila Michener is an associate professor of government and public policy at Cornell University. Her research focuses on poverty, racism, and public policy—with an emphasis on how racially and economically marginalized populations can influence the policies that most acutely affect their lives. She is author of Fragmented Democracy: Medicaid, Federalism, and Unequal Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2018).