Your Economics Are On Backwards: Why Trump’s Budget Will Not Spur Growth

May 23, 2017

By Marshall Steinbaum, Eric Harris Bernstein

Donald Trump’s budget, released today, is a lie on top of a joke. A lie because it leaves off the enormous cost of the president’s proposed tax cuts for the rich and a joke because it relies on comically exaggerated forecasts of supercharged economic growth to generate additional revenue so that Trump can claim he is balancing the budget. One particularly egregious example: He proposes eliminating the estate tax at the same time he relies on the revenue it generates to plug budget holes.

Many have ably pointed out the basic math error of leaving out tax cuts, but there is a more fundamental economic error: Trump’s budget – like so many conservative budgets before – relies on the false assumptions that tax cuts for corporations and the rich will generate growth. They do not. And they may even do the opposite.

Tax cuts for the top are sold on the notion that if businesses and individuals had more cash and a greater incentive to earn more cash, they would invest more in capital, employees, and new business ventures. The problem with this argument is that corporations and the wealthy are already historically profitable, earning near-record income, and sitting on vast mountains of cash, yet they are still not investing as we would expect or hope.

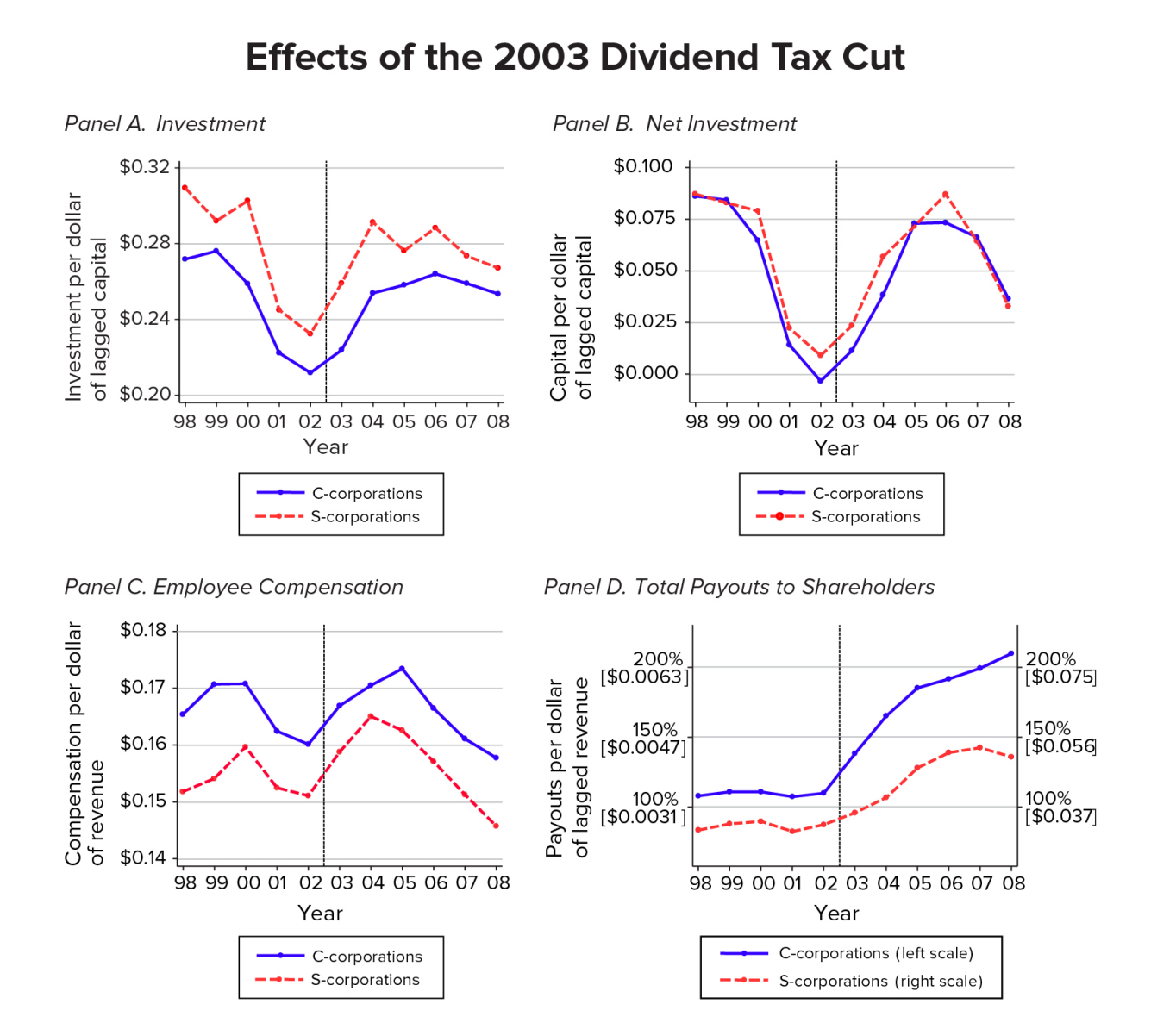

Furthermore, recent tax cuts show that, rather than boosting investment or employment, lower effective corporate rates only result in more income for the rich. This is exemplified in the figure below, which shows how beneficiaries of the 2003 dividend tax cut (“C-corporations”) showed no change in investment or employee compensation compared to non-beneficiaries (“S-corporations”). The only thing the 2003 tax cut did was raise payouts substantially. The 2004 “repatriation holiday” delivered similar results: Corporate investment remained flat, while payouts shot up.

Figure 4 from Roosevelt’s “Fool Me Once” report: Yagan (2015) compared C-corporations, whose dividend taxes were cut in 2003, to S-Corporations, whose dividends were unaffected. The former are the treatment group for this study, and the latter are the control group. Each panel of this chart presents a different corporate use of funds: gross and net investment, payroll, and payouts to shareholders. Contrary to neoclassical theory, corporate investment did not respond to an increase in the after-tax return to investment, represented by the dividend tax cut. Payouts to shareholders, on the other hand, did— shareholders realized the entire windfall from the tax cut.

The reason regressive tax cuts don’t spur growth is that, rather than incentivizing investment or employment, lower rates for top earners only encourage them to negotiate for higher salaries. Under President Eisenhower, the top marginal income tax rate was 90 percent. This rate created a de facto maximum income, because it simply made no sense to demand exorbitant pay packages. Instead, companies spent these dollars elsewhere – either in expanded capacity or higher wages for their workers. Not shockingly (except, perhaps, to conservatives), growth was robust.

Today’s economy is the opposite: Rates are so low that an additional dollar of income for the rich running or owning businesses is almost always more appealing than spending that additional dollar on investment or wages. And growth is sluggish, at best.

If conservatives want to the tax code to encourage growth, it needs to discourage runaway earnings at the top. That would channel more funds into wages and investment, and lead to a better economy.