To Increase the Supply of Workers, Our Economy Needs Childcare

March 1, 2023

By Mike Konczal

On Tuesday, the Department of Commerce announced the CHIPS for America Funding Opportunity, which is part of the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act designed to rebuild the semiconductor industry in the US. My colleague Todd N. Tucker gave a rundown of the innovative safeguards and incentives that are included here.

Though it’s just one piece of an overall set of requirements, “applicants requesting Direct Funding over $150 million must submit a plan to provide their facility and construction workers with access to child care.”

As the “CHIPS for America Fact Sheet” notes:

This first-of-its kind commitment will be essential to getting people—especially women—into the workforce. A recent review of research on child care costs and women’s labor supply found that a 10 percent decrease in the cost of child care leads to a 0.5 to 2.5 percent increase in maternal employment. That effect is even stronger for mothers with lower incomes. If women participated in the labor force at the same rate as men, there would be more than 10 million additional workers. Making it easier for women to join the workforce will therefore be critical to the success of individual projects and of the program as a whole.

There’s an additional argument for why this requirement is especially important for our current economy: While labor force participation has recovered quickly to 2019 levels since the beginning of the pandemic, levels were already too low and declining in 2019 (and in 2007, before the Great Recession). Strong demand, by itself, is not solving this problem. Instead, for the economy to continue to grow, we need policies that boost labor force participation.

There’s been a remarkable recovery in the labor market over the past two years: At 3.4 percent, the unemployment rate is the lowest it’s been since the 1960s. The labor force participation rate also provides evidence for the quick recovery. Employment-to-population ratios have returned to near where they were before the pandemic, for all groups of people. For some groups, notably Black men, the rates are even higher than they were before the pandemic.

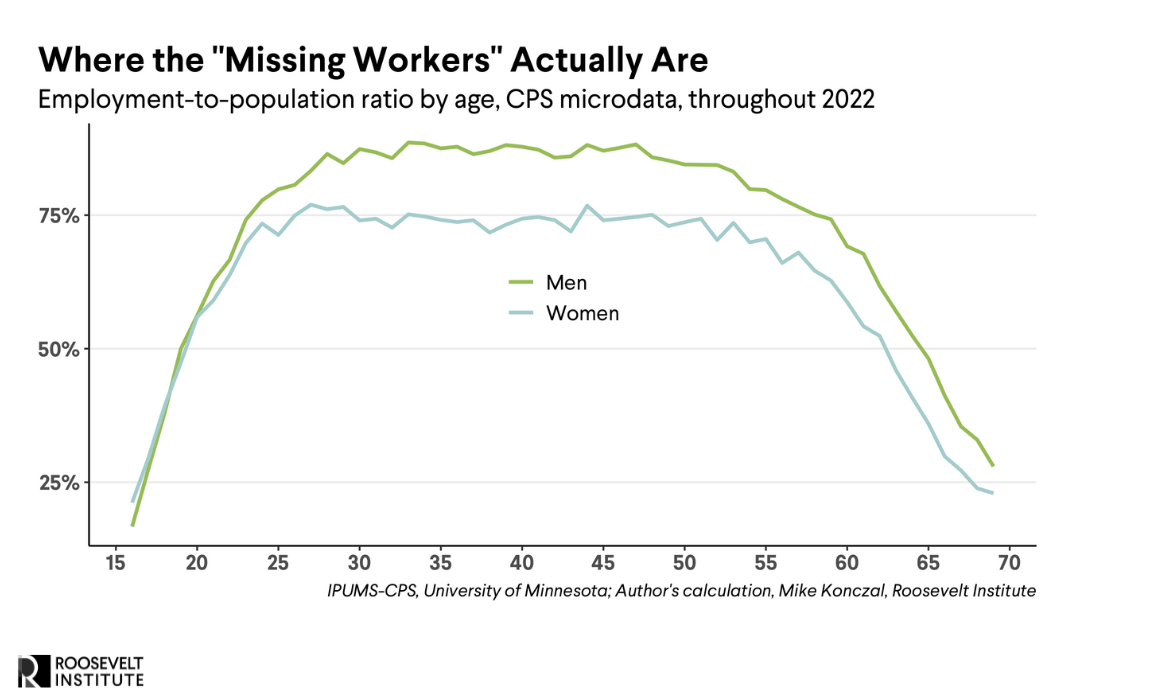

But simply returning to 2019 levels isn’t good enough. Recently, there has been a big debate among Federal Reserve economists over “missing workers” (who largely turned out to be in their 70s). But this debate completely ignored one group of people from which we know many workers are missing: women.

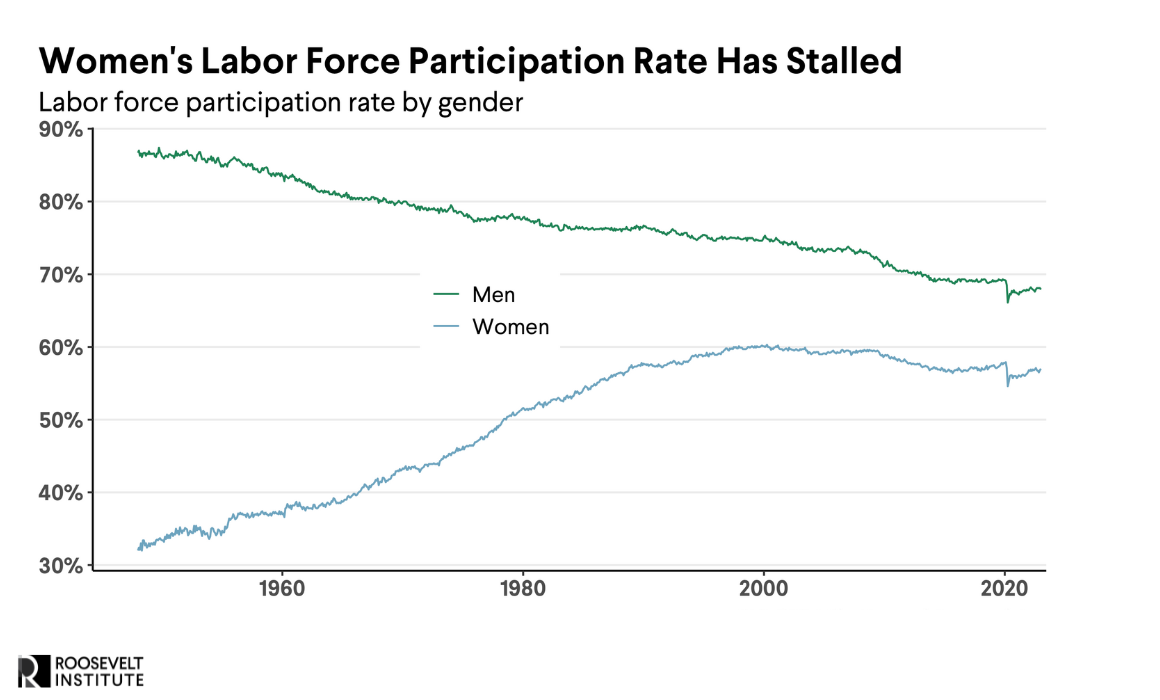

Our social policy is not designed to give people—particularly women and parents—the support they need to work jobs. Women’s labor force participation increased steadily throughout the 20th century, until it hit a ceiling of 60 percent starting in the late 1990s. It has since declined slightly. This level is well below peer countries, many of which offer more social services designed to help families and workers.

Figure 1

And for further context, Figure 2 shows the age distribution of employment-to-population across age groups in 2022.

Figure 2

We need policies that continue to help boost labor force participation rates. Though it is possible that demand will pull people into the labor force, government support can facilitate that process. Many people, including myself, had hoped that demand alone would cause higher increases in labor force participation—reversing decades of stagnation and declining rates. But after two years of high openings-to-unemployment ratios and other measures of a high labor demand, increases in labor force participation should also be higher.

Just as we need physical infrastructure like roads to get workers to factories, we need social infrastructure—like childcare—that supports workers, too. And just as any individual firm will have an incentive to try to compete away workers from peers in an already tight labor market, coordinating firms to increase participation overall is an important labor market move. Solving these kinds of investment and coordination problems is where the government plays an important role.

As our nation moves to build things, it is important to remember that supporting families is essential to expanding the supply side. As Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen argued in coining the term “modern supply side economics” in January 2022 to describe the Biden administration’s economic approach: “Labor supply has been a concern in the United States even before the pandemic . . . The lagging labor force participation rate is driven in large part by a combination of factors that disincentivize work, such as inadequate paid leave and high childcare costs.”

Care is exactly the kind of thing that could get lost in a narrow focus on supply chains and materials, but it’s one of the things we know matters most for workers.