Three Takeaways from the Roosevelt Institute’s Permitting Reform Forum

April 21, 2023

By Kristina Karlsson

On Tuesday, March 21, 2023, the Roosevelt Institute hosted Building the Green Transition: A Justice-Centered Vision for Permitting Reform—a one-day, in-person conversation in Washington, DC, about progressive proposals for permitting reform, featuring experts in government, academia, industry, and environmental policy.

Since the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the largest climate investment package in history, rapidly building out renewable energy capacity has been top of mind for climate advocates. As a result, policymakers and advocates are debating how best to efficiently greenlight an unprecedented number of renewable energy projects. Many of these discussions have identified reviews conducted under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)—the bedrock federal environmental protection law in the US—as the key obstacle to the build-out of renewables. NEPA requires that agencies review the environmental impacts of projects that are conducted using federal dollars or that require a federal permit, and requires that communities are consulted and notified of the findings. Based on the perception that NEPA reviews are hindering renewable energy project efficiency, proposals have surfaced suggesting cutting community participation and imposing time and page limits on environmental impact assessments. But to speed up the development of renewable energy, the federal government doesn’t need to limit democratic participation and planning or environmental protection.

Building out renewable energy capacity is dependent on trust. Robust community engagement in a fair permitting process is essential to the long-term success of the renewable transition. We need progressive reforms that strengthen NEPA and target the specific sources of delays within the process, not deregulation. And we need to tackle the much larger obstacle to the build-out: transmission. Transmission capacity and connectivity pose a serious challenge to implementation and must be addressed directly. This cannot be solved by proposals that weaken NEPA.

Through permitting reform done well, paired with policies to invest in transmission capacity, we can shape the energy system we want and embed our democratic values into the clean energy transition. If we don’t take seriously the implications of slashing NEPA, we risk losing public trust in the largest economic transformation we’ve ever attempted.

***

On March 21, 2023, the Roosevelt Institute hosted a day of discussion on the many dimensions of this debate for experts from academia, government, frontline communities, and the clean energy private sector. Over the course of the day, participants offered ideas for how to, in Earthjustice President Abigail Dillen’s words, “reimagine the rules to drive genuine clean energy, to create a shared vision of what a clean and fair energy system looks like, and build the trust to align around that.” These included ideas to reform NEPA and build out even more vital transmission capacity in ways that reflect the interests of both justice advocates and renewable developers.

Three key points of consensus emerged:

- NEPA review is not the primary cause for delay in renewable projects;

- Transmission capacity and gatekeepers to connecting to the energy grid are the biggest threat to timely renewable deployment; and

- Progressive reforms to NEPA that strengthen, rather than cut, community engagement would build trust that could help ensure the long-term success of the renewable transition.

NEPA review is not the primary cause for delay in renewable projects.

Both fossil fuel-backed politicians and climate experts have called for “streamlining” NEPA by weakening community engagement and environmental review requirements in order to speed up the permitting process. But, at least for climate experts, these proposals are driven by crucial misunderstandings about the extent and sources of delay to renewable build-out and how NEPA fits into the build-out.

First, the permitting process involves all levels of government—federal, state, and local—and integrates permits from the Clean Water and Clean Air Acts, in addition to NEPA reviews. Discussing only the federal level and focusing solely on NEPA misrepresents the multifaceted permitting process, in which sources of delay are varied—often not found at the federal level, and not stemming from NEPA review. As Anthony Rogers-Wright, director of environmental justice at New York Lawyers for the Public Interest, explained, delays to renewables stem from issues of federalism—with multiple levels of government layering their own protections and review processes—and local political economies. The build-out of renewable infrastructure will require compliance with state and local permitting bodies (in addition to federal), and the politics that impact them.

Second, when we do look at NEPA, data on the length of the review process shows much more nuance than hand-picked case studies that are being cited by proponents of deregulation. The delays stemming from Environmental Impact Assessments (EIA) and litigation have been overstated in permitting debates. Far fewer NEPA-impacted projects go through these assessments, and median times for the projects that do go through the full review are shorter than oft-cited average figures. The Council on Environmental Quality estimates that projects that required an EIA (the most intensive review process) accounted for less than 1 percent of all NEPA-reviewed projects, and only 5 percent required Environmental Assessments (a less intensive process), while 95 percent of NEPA projects are categorically excused from environmental review entirely.

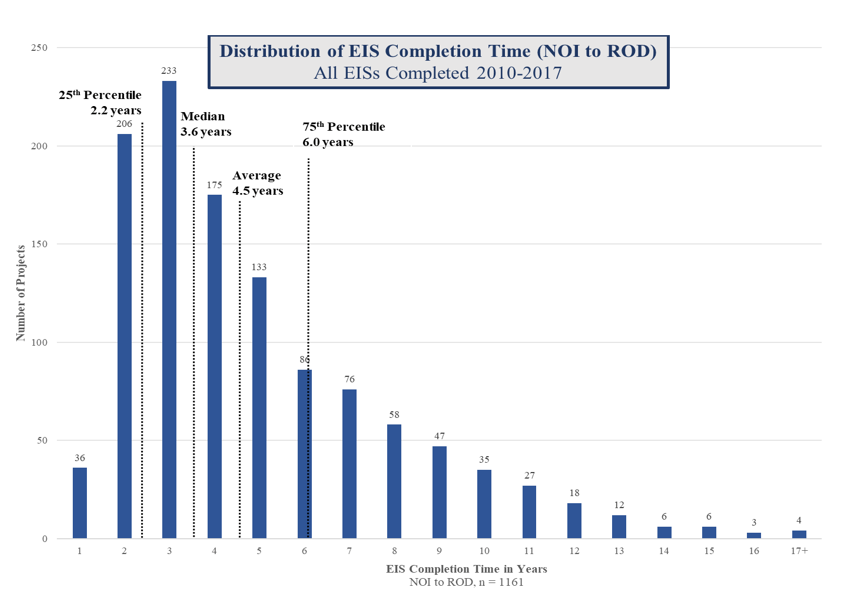

A national study led by Dr. Jamie Pleune, associate professor of law at the University of Utah Wallace Stegner Center for Land, Resources, and the Environment, looked at the review time for environmental impact statements in all NEPA projects from 2010 to 2017, and found that the “vast majority of (environmental impact assessment) decisions are made within a pretty short time frame and then you have this long tail that skews the mean [which is] 4.5 years. But the median, reflecting the majority of projects, is only 3.3 years and the top 25% of projects take 2.2 years.” This graph of the study’s findings shows clearly how a small number of projects with very lengthy review times have skewed the average.

The experience of Adam Cohen, CEO of Ranger Power, a utility scale solar developer, reflects Dr. Pleune’s data. Cohen explained that transmission connectivity actually takes much longer than NEPA review. Once solar fields or wind farms are built, they must be able to connect to the grid of large-scale transmission lines in order to deliver renewable energy to households. This process causes significant delays. “We’re looking at six to eight years to connect to the queue,” Cohen said, “and that has created an unworkable situation where you have these local permitting bodies that have put their neck out for your project and then you’re going to wait another three, four, five, six years to connect to the grid . . . That’s a problem we need to solve and it’s not NEPA or public engagement, it’s a lack of investment in our transmission system.”

Often, the term “permitting reform” conflates the very real difference between the NEPA review process and the much more challenging process of connecting to existing transmission lines or getting necessary investment in new transmission. It is therefore crucial to be specific when identifying sources of delay and the policy tools that will solve them.

Transmission capacity and gatekeepers to connecting to the energy grid are the biggest threat to timely renewable deployment.

Unlike the procedural quick fixes to NEPA that have dominated the permitting conversation, solving the transmission bottleneck requires investment and a reckoning with the political and economic incentives of corporate and administrative gatekeepers.

To meet emissions reductions targets and fully implement the IRA, Nathanael Greene, senior advocate for the Renewable Energy, Climate & Clean Energy Program at the Natural Resources Defence Council (NRDC), estimates we need to “grow large interstate transmission at 9 percent a year over the next decade.” Large interstate transmission is typically at least 1,000 megawatts and touches three separate states. These lines are essential for moving renewable energy from its points of generation to the markets that it is intended to serve, and thus critical to utility scale projects. Tyler Norris, vice president of development at Cypress Creek Renewables, noted that even at the distributed scale, bottlenecks in large transmission hinder local projects. Right now, there are 8,000 projects in the interconnection queue across the country, waiting to connect.

Unfortunately, existing incentives do not push investor-owned utilities (IOUs) to take on large-scale regional transmission projects. Panelists discussed solutions to address issues of corporate power and coordination as key blockages. The power that IOUs wield and the market incentives that bear upon them result in very few new regional transmission projects. Christine Powell, deputy managing attorney of the Clean Energy Program at EarthJustice, shared that “investor-owned utilities own 70 percent of all the electricity in the country and they own the majority of existing transmission lines.”

IOUs are beholden to their profit-maximizing shareholders and undertake capital projects to secure those profits. But, because there is far less oversight and transparency required in upgrading local lines already in their jurisdiction, IOUs are more likely to make capital improvements locally and are disincentivized from bidding to build regional transmission lines, which require more oversight, even if the region needs this capacity. To address this issue, FERC is proposing requiring a more transparent process for local projects in order to determine if they are in fact a better use of resources than larger regional projects.

There is also the issue of overlapping jurisdictions and coordination. As Suedeen Kelly, former Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) commissioner, laid out, FERC has jurisdiction over interstate transmission planning and cost allocation but not siting. States have jurisdiction over where transmission projects are sited, and in many states these two planning processes are not integrated.

To address these problems, panelists offered a few key proposals, including:

- The SITE Act, introduced by Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI), aims to alleviate the coordination issue by designating FERC as the siting authority in transmission projects.

- Submit comments to the FERC rulemakings. Christine Powell encouraged transmission and renewable experts to submit comments to the ongoing FERC rulemakings aimed at interconnection backlog, cost allocation, and regional planning.

- The CHARGE Act, introduced by Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA), aims to hold utilities accountable to their climate commitments, establish an advisory committee to improve governance in grid operators, and ensure resiliency of the grid.

These reforms will go a long way to speed the renewable transition and should be of primary importance to climate advocates concerned about building efficiently. Even as we work to mitigate the outsized power of utilities, there is potential for collaboration right now. Suedeen Kelly shared an inspiring example from her work as legal representation for the Morongo Band, where the tribe entered into a leasehold interest agreement with Southern California Edison to build a new high-voltage transmission line through Morongo land. The tribe, the utility, and the ratepayers all benefited from the deal, and the FERC decision paves the way for win-win-win collaboration in the transmission build-out.

Progressive reforms to NEPA that strengthen, rather than cut, community engagement will build trust and ensure the long-term success of the renewable transition.

The renewable transition provides an opportunity to affirm our democratic values and create procedural justice. The status quo and the proposals on the table will result in the opposite. Fortunately, environmental justice advocates and progressive permitting experts understand the complexity of the NEPA permitting process—both as participants and as practitioners—and have ideas for reform that serve the renewable transition and communities.

In her national NEPA review study, Dr. Jamie Pleune found that two causes for delay are lack of capacity and permitting coordination. These two issues far outweighed delays stemming from extended community review and can be solved with simple fixes, some of which are already in motion.

Proposals:

- Rapidly disburse the $750 billion set aside in the IRA to implement NEPA. This funding will go a long way in increasing administrative and personal capacity.

- Use NEPA as air traffic control for all the permits involved. Share data and analysis between agencies to increase efficiency and consolidate into one timeline. Fast 41 is an existing policy that uses enhanced coordination to speed up certain projects, including renewable energy projects.

Both developers and communities have raised concerns about unpredictability under the current NEPA processes. Communities want to make informed decisions about which projects to include in their neighborhoods and the cumulative impacts they will face, and developers want to know when and if their project will be approved. Two key reforms to make the process more predictable are earlier community engagement and more explicit rules about when environmental impact findings will result in a project not moving forward.

The community engagement process is flawed. But it should be strengthened rather than weakened. Community engagement is currently conducted toward the end of the permitting and review process when site selection, designs, and funding are already in place. At that point, it is very difficult for communities to influence the shape of a project within the NEPA process, and they must often resort to litigation or organizing.

Fermina Stevens, chairperson for the Elko Band Council, shared that the tight time constraints on tribes for submitting responses to proposed projects can force them to oppose a project by default because there is not enough time for them to do a thoughtful review. This echoes Jungwoo Chun, Postdoctoral Impact Fellow at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Climate and Sustainability Consortium, whose research studies sources of community opposition to renewable projects in particular. He finds that much of the community opposition documented was due to lack of public engagement when input would be meaningful to the project. It is crucial that the process build trust and foster collaboration between communities and developers in order to move the renewable transition forward.

Proposals:

- Start community engagement much earlier in the process. Maria Lopez-Nuñez, deputy director of organizing and advocacy at Ironbound Community Corporation, shared that, “When industry comes to me first, we can negotiate. We have community meetings with them before they even go through the permitting process; we’re able to solve things.” This sentiment was echoed from the developer’s perspective as well. Adam Cohen of Ranger Power shared that his firm does proactive community engagement before the permitting process and finds that it speeds up the project as a whole.

- Undertake community engagement with a neutral party. Aminah Ghaffar, community organizer for 7 Directions of Service, raised the issue of intimidation and unfairness in the community engagement process. In order to embed trust, there should be a neutral mediator. Jungwoo Chun and his colleagues at MIT plan to pilot the Renewable Energy Facility Siting Clinic to meet this need.

- Make the comment system more user-friendly and accessible to community members that do not have access to computers or struggle to attend hearings during the workday.

- Use programmatic environmental review so a community can discuss all the potential projects in its area and pick the good ones it wants and oppose harmful ones.

To create more certainty about outcomes, proposed reforms include:

- Substantively attach cumulative impact analysis with the existing “no action alternative.” Cumulative impact analysis takes into account the existing pollution burden of a community and weighs the additional impact of a new project. NEPA’s “no action alternative” should be automatically triggered by a threshold of additional environmental impact. New Jersey law No. 2212 already does this; if a project results in an increase of pollution in an already overburdened community, then the law shall deny the application.

- Implement a post-decisional learning loop. A review of the success or shortfalls of past projects will help ensure that NEPA decisions become more consistent and that lessons learned are used in subsequent projects.

All of these proposals seek to address the most prevalent NEPA concerns that we gathered from career permitting experts, academics, and environmental justice advocates. While we maintain that transmission, rather than NEPA delays, is the greatest threat to the build-out of renewables, we are intent on providing a progressive vision for NEPA reform that can help reduce the power of fossil fuels and support communities that have suffered the brunt of climate change in the US. Importantly, these proposals are also born from the belief that communities should be seen as partners, not obstacles to progress.

Conclusion

The permitting debate needs to be based on data and research, and needs to engage with the nuanced processes and power dynamics at play. Flattening the task of efficiently building our renewables to center on weakening community engagement in NEPA is misguided in its identification of the problem, and offers a harmful solution. Our event, Building the Green Transition: A Justice-Centered Vision for Permitting Reform, began to outline a progressive vision for reforming NEPA and transmission capacity processes.

Too much of the current permitting conversation focuses on cutting community engagement timelines and placing limitations on environmental impact assessments in ways that will cause harm to frontline communities. Frontline communities–predominantly, Black, brown, Indigenous, and low-income–are not naive to the severity of climate change and the urgency of action, as Dr. Nicky Sheats, PhD, MPP, Esq., director of the Center for the Urban Environment at Kean University, points out: “We want to fight climate change in the EJ communities because it’s going to hit our communities first and worst. But we don’t want our communities sacrificed along the way.” Justice advocates are intent on building out a renewable transition, but for them the permitting debate is not only about the speed of building good stuff but about ensuring only the right stuff is built. The stakes are high.

It is no secret that this ongoing debate is heated. Climate advocates and fossil fuel proponents alike have labeled environmental justice activists as naive to the role permitting plays in building out renewables and as the blockers of progress. Enabling this scapegoating is a misunderstanding of the true causes for delay and an aggressive disregard for progressive alternatives like those unveiled by Sen. Ed Markey (D-MA) in his keynote. The suite of proposals outlined in this summary are a crucial first step in advancing the reforms that experts and communities have sought for years and that will build a renewable transition based on trust.