The US Medical Debt Crisis: Catastrophic Costs of Insufficient Health Coverage

May 15, 2025

By Stephen Nuñez

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- I. Medical Debt: What It Is, Who Has It, and Why

- II. The Affordable Care Act and Its Enemies

- III. The Financial Consequences of Medical Debt

- IV. Biden Administration Policies Addressing Medical Debt

- V. Trump Administration and Congressional Actions Worsening the Medical Debt Crisis

- Conclusion

Introduction

Good health care in the United States requires good health insurance, which provides access to the preventive and emergency medical care that is critical to our health and well-being. But good health insurance in the US is also a shield against financial ruin, a protective benefit that receives comparatively little attention in health-care policy debates. To the uninsured and underinsured, an injury or illness can result in crippling debts that simultaneously impoverish their families and close off pathways to economic mobility. Medical debt is a serious problem in the US, and, not surprisingly, the poor and those in poor health bear the brunt of this dysfunction. Medical debt is also disproportionately a problem for Black and Hispanic people, who, because of a history of systemic discrimination, are more likely to be low-income and more likely to live in states that have exacerbated this problem by refusing federal funds to expand public health insurance coverage.

This paper examines medical debt in the United States: its causes, its distribution, and its consequences, paying special attention to the ways in which medical debt has contributed to the racial wealth gap and limited economic mobility for Black and Hispanic households. Understanding why and where medical debt is a problem in America today requires familiarity with the Affordable Care Act (ACA), its limitations, and past and current conservative efforts to sabotage it in courts, in Congress, and at the state level. And that means an analysis of the structure of our health-care system, including Medicaid, the ACA health insurance marketplaces, and employer-sponsored insurance (ESI).

Key takeaways are as follows:

- Medical debt is driven by current or past periods of uninsurance and underinsurance and disproportionately affects low-income, Southern, and Black and Hispanic Americans.

- The Supreme Court’s decision to make voluntary the Affordable Care Act’s intended mandate for states to expand Medicaid left millions uninsured in a “coverage gap” between Medicaid and private insurance.

- Medical debt can cause material suffering, limit economic mobility, and widen the racial wealth gap through a variety of financial consequences ranging from lower credit scores to bankruptcy.

- While the Biden administration made numerous changes to the health insurance system to lessen the impact of medical debt and extend insurance overage to more Americans, the Trump administration and current Congress are not only seeking to roll back these reforms but also threatening to make massive cuts to Medicaid that would leave millions more people vulnerable to the burden of medical debt.

- Policy reforms can ease the medical debt crisis:

Medical debt is not inevitable. Rather, it is the product of decades of dysfunctional health-care policy, a market-oriented insurance system, and a patchwork of safety net programs with notable gaps. Biden administration efforts over the past several years have shown that our health-care system can be strengthened to extend insurance to millions more working-class people and help millions more upgrade their insurance coverage with better plans, at incrementally small costs. But the Trump administration is now poised not only to undo these steps but to enact savage cuts to federal health-care spending that will supercharge the medical debt crisis and together leave millions of people, disproportionately Black and Hispanic, uninsured and underinsured.

Medical debt is not inevitable. Rather, it is the product of decades of dysfunctional health-care policy, a market-oriented insurance system, and a patchwork of safety net programs with notable gaps.

I. Medical Debt: What It Is, Who Has It, and Why

Medical debt is, narrowly defined, money owed to medical service providers such as hospitals and private practices for treatments and procedures. Those that have no health insurance may accrue medical debt if they do not have sufficient savings to cover the cost of care. But medical debt can be a problem for people with health insurance as well. This debt may be the result of past periods without health insurance (e.g., when unemployed), but it may also come from gaps and inadequacies in the coverage they previously had or currently have. Health insurance plans may not cover needed procedures or procedures done at “out-of-network” facilities, they may require large copays for certain types of care (e.g., hospital stays), and they may have high deductibles (expenditures that the insured must pay out of pocket before insurance covers remaining costs).1 This is the problem of “underinsurance.”

While there is no standard definition of underinsurance, the Commonwealth Fund considers adults with insurance plans underinsured if they experienced at least one of the following in a year:

- Out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaling 10 percent or more of household income

- Out-of-pocket costs, excluding premiums, equaling 5 percent or more of household income, if low income (<200 percent of the federal poverty line)

- Deductibles equaling 5 percent or more of household income

Using this definition, the Commonwealth Fund finds that 23 percent of working-age adults in the US who had consistent insurance coverage2 in 2024 were underinsured and thus unable to access affordable care. To make matters worse, individuals may not fully understand what their insurance covers and where (if they have any choice in where and when to seek care). In other words, individuals may learn that they were underinsured only after they receive the bill for a procedure and realize they are unable to handle the costs despite their coverage.

Being uninsured or underinsured drives medical debt by leaving individuals financially vulnerable when health care becomes a necessity, but it can also drive debt indirectly by discouraging preventive care. Uninsured and underinsured individuals, such as those with high-deductible insurance plans, do not shop around for bargain health care or prioritize preventive care—in part because they do not have the information required to do so. Instead they simply dial back on all health-care expenditures. Expenditures equal the quantity of a good purchased times the purchase price, so falling expenditures can sound positive—but in American health care, where eminent scholarly publications have titles like “It’s the Prices, Stupid” and “It’s Still the Prices, Stupid,” the implications of cost cutting are clear: People are forgoing needed care. This means they will not receive care that identifies and treats health issues before they become serious. And once an issue becomes too serious to ignore, it may cause health events, catastrophic costs, or both.

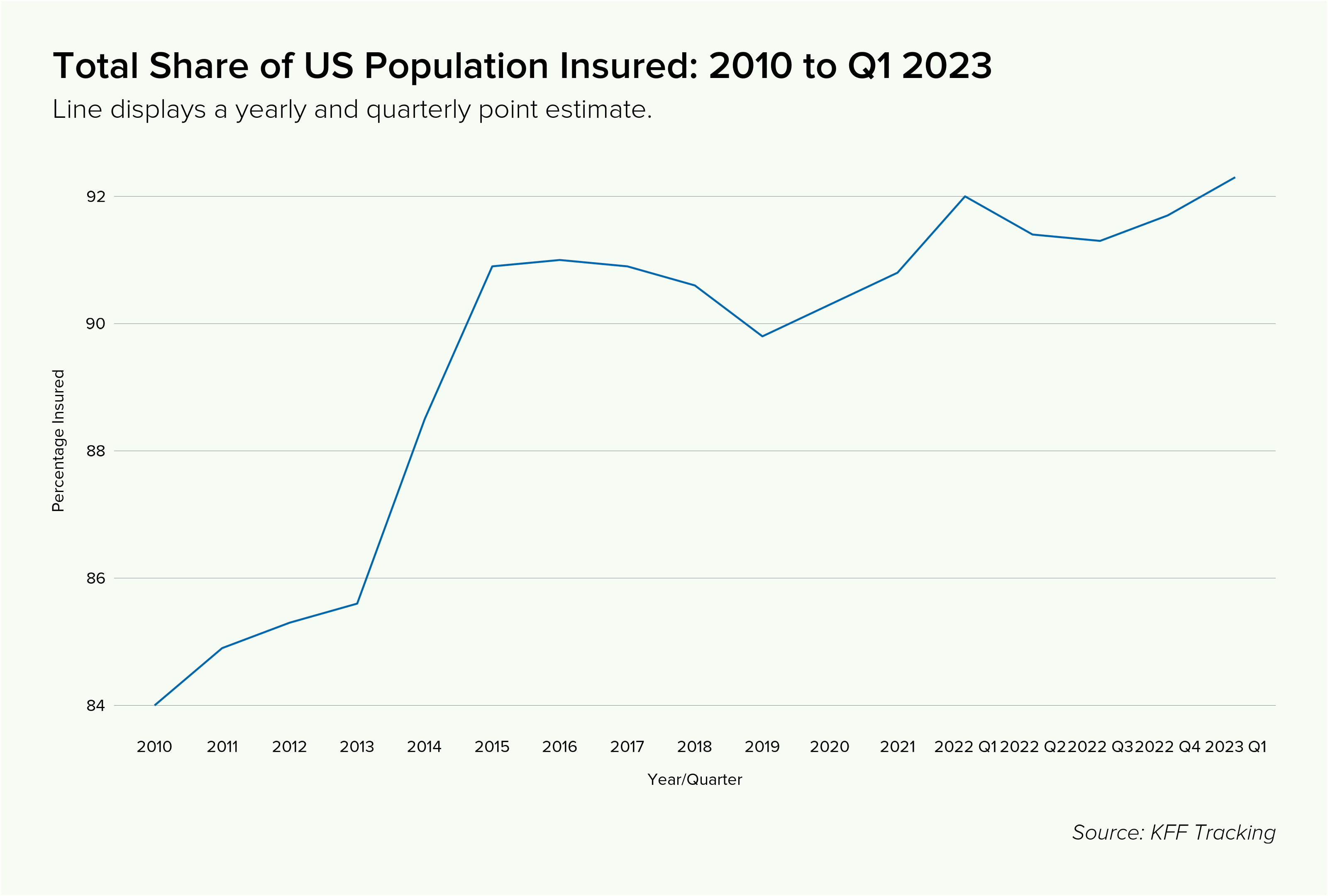

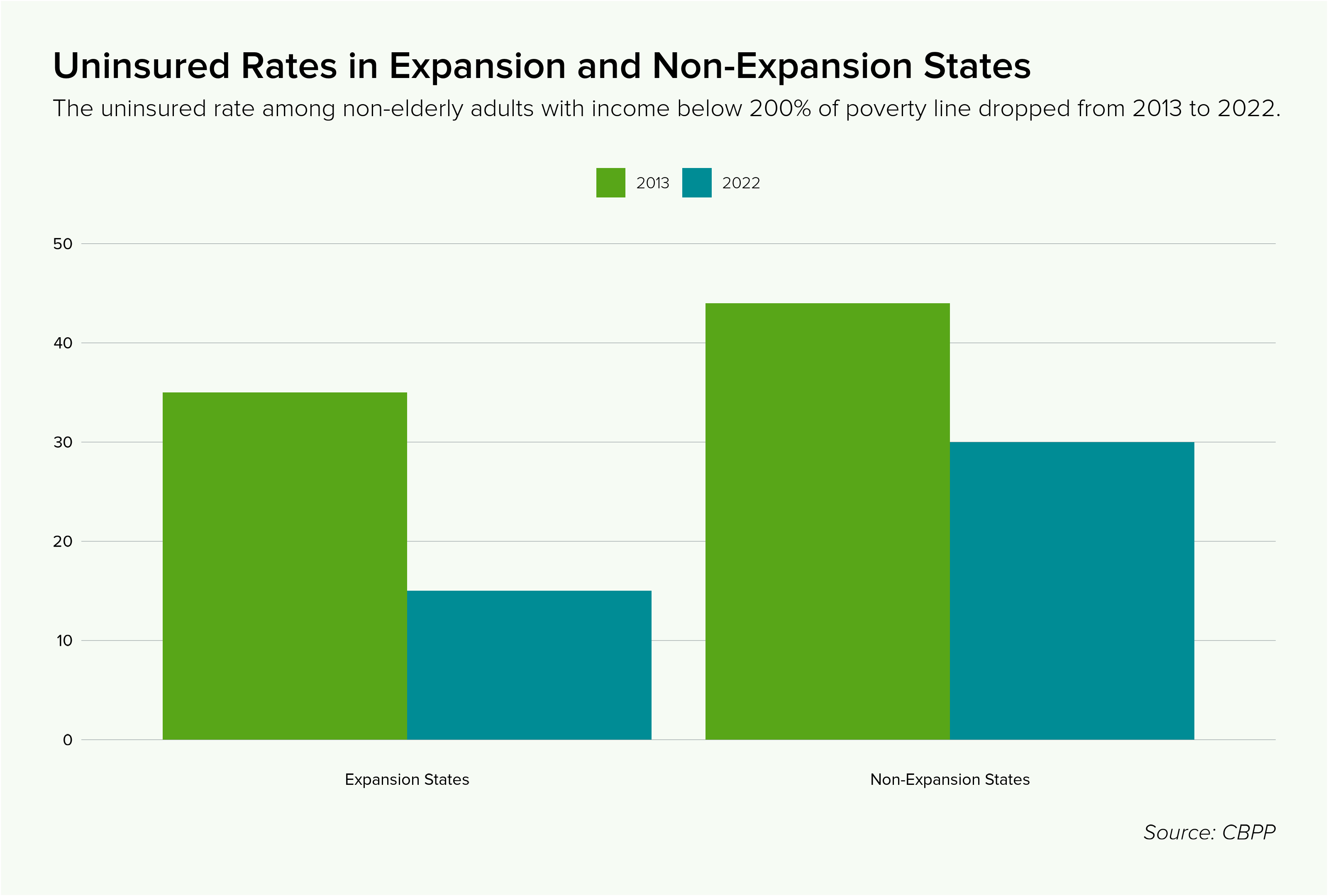

Even though more than 90 percent of US residents have some type of health insurance coverage, and even after the ACA cut the uninsured rate in half (see Figure 1), the prevalence of underinsurance and gaps in previous insurance coverage mean medical debt remains a serious problem. Using data from the 2021 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), researchers at the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) found that 20 million adults (almost 1 in 12) owed “significant” medical debt to a health-care provider.3 Of those, 14 million had medical debts over $1,000 and 3 million had debts over $10,000.

This number rises when we consider a more expansive definition of medical debt. For example, if someone uses a credit card or bank loan to pay off a debt to a medical service provider, they may still be left with a persistent debt burden. In a companion report to the above, KFF researchers conducted a survey specifically to estimate the debt Americans carry that originates from medical services even if not owed directly to medical service providers. This includes debt they owe to a bank, collection agency, or other lender; any bills they have put on a credit card and are paying off over time; or any debt owed to a family member or friends. They found that an estimated 41 percent of American adults (~107 million people) carried some form of medical debt and that 24 percent of American adults (~62 million people) had medical debt that was past due or that they were unable to pay. Among those with medical debt, nearly half (44 percent) reported owing at least $2,500, and about one in eight (12 percent) said they owe $10,000 or more.

Figure 1

Medical debt is widespread, but certain groups suffer it disproportionately. Those who rate themselves as having only fair or poor health are more likely to accrue medical debt because of increased health-care utilization. Low-income individuals are also more likely to accrue medical debt, both because they are less likely to obtain (good) health insurance from their employers and because they have fewer assets to handle medical expenses when they arise.4 In the KFF survey described above and using the more expansive definition of medical debt, 57 percent of adults with household incomes under $40,000 said they currently have debt due to medical or dental bills. Middle-aged people are more likely to accrue medical debt because people are more likely to develop health problems as they age, and also because they are not yet eligible for the robust health insurance coverage that Medicare provides. They are often also responsible for the medical care of minor children and thus have additional exposure to significant medical bills. More than half (52 percent) of respondents in this age group reported current health-care debt.

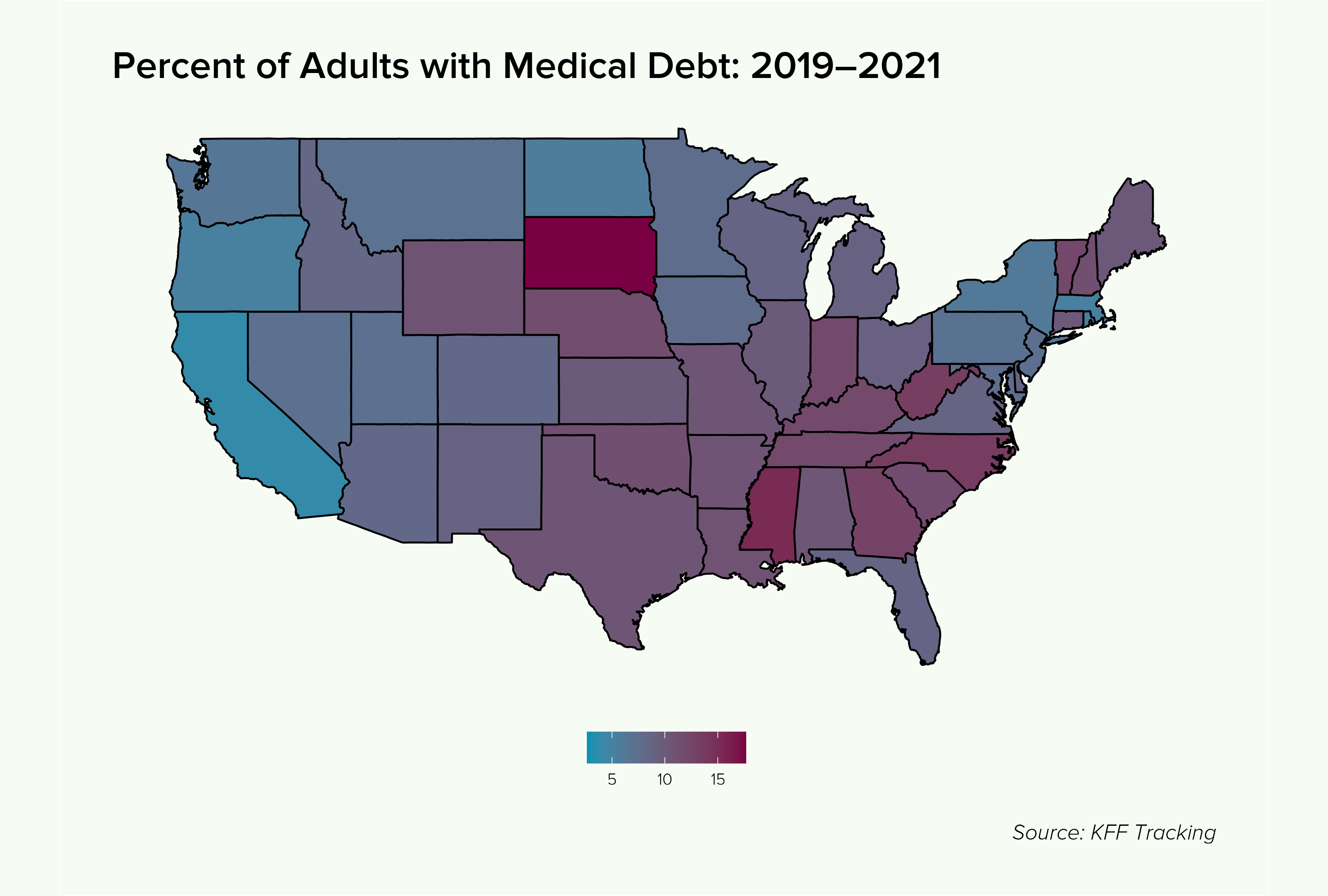

Lastly, Black and Hispanic people are disproportionately likely to hold medical debt—56 percent of Black adults and 50 percent of Hispanic adults owe money for a medical or dental bill, compared with 37 percent of non-Hispanic white adults. This is partly because Black and Hispanic individuals are more likely to be lower income and less likely to have substantial savings than otherwise similar non-Hispanic white people due to a history of racial discrimination and segregation. This sort of group discrimination means that a low-income Black or Hispanic individual is at a disadvantage even when compared to a low-income white person, including because the latter is more likely to have friends and family that are not low-income or savings-constrained and can potentially help out in an emergency. This may, in part, be why a recent Brookings Institution study found that Black households with health insurance coverage are as likely to hold medical debt as non-Black households that do not have health insurance coverage.5 Black and Hispanic individuals also suffer disproportionately from medical debt because of where they live. They are more likely to live in the South or Southeast (with a large population of Hispanics in Texas specifically), and people across the South are more likely to accrue medical debt than elsewhere in the nation: Roughly half of Southerners hold medical debt, versus one-third elsewhere. To understand why requires a detour into the structure and history of the Affordable Care Act.

II. The Affordable Care Act and Its Enemies

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was a signature policy achievement of the Obama administration (often referred to as “Obamacare”) that fundamentally reshaped American health-care policy and insurance markets. In addition to prohibiting health insurers from denying insurance coverage to individuals based on preexisting health conditions and extending the age up until which a child could be covered under a parent’s family insurance plan to 26, the ACA created “Medicaid expansion” and a health insurance marketplace where individuals could purchase health insurance.

Medicaid offers two eligibility pathways. The first is categorical eligibility gained through, for example, disability status. The other is through income means-testing. Prior to the ACA, this latter pathway was extremely limited for so-called able-bodied adults, those that have not received disability status. Parents of young children whose income fell far below the federal poverty line (FPL) could receive Medicaid while those without dependent children generally could not. States have some discretion in setting this threshold, with the median for parents being 34 percent of the FPL (this is extremely deep poverty—an income of less than $11,000 per year for a family of four).

The ACA was written to require states to expand Medicaid coverage to any otherwise eligible person, whether or not they had children, who lived in households at or below 138 percent of the FPL.6 At the same time, the ACA created an “employer mandate,” which required companies with 50 or more employees to offer adequate and affordable health insurance to its workers. Those who were self-employed or who worked for employers below the mandate threshold that did not provide such coverage were intended to obtain health insurance through the ACA individual health insurance marketplace (sometimes called “the exchanges”) where they could purchase insurance with help from the federal government in the form of “premium tax credits” to help absorb the cost of premium payments. These scale in size according to income and can be calculated in advance and factored into the monthly costs of insurance plans—both when choosing a plan and paying the monthly premium.

The use of the phrases “was written to” and “were intended to” should signify that all did not go according to plan. Some problems immediately arose because of the way the law was written. The employer mandate, as noted, set required coverage and affordability standards for employer-sponsored insurance (ESI). Employers must offer a plan with coverage equivalent to a “bronze tier” plan on the ACA marketplace, the lowest of several tiers of progressively stronger coverage. Bronze tier plans must cover 60 percent of total health-care costs and may have lower premiums than “silver,” “gold,” or “platinum” plans but higher copays or very high deductibles. ESI must also be “affordable,” with employers having the choice of three different “safe-harbor” standards to meet this requirement. Advocates have argued that the coverage standard was set too low and the affordability standard was set too high, meaning employees at companies that did the bare minimum would end up with limited coverage in exchange for costly premiums.

This would not in itself be a major problem except for another provision in the the ACA, the so-called employer firewall: Otherwise eligible individuals who work for an employer that offers health insurance can always choose to purchase health insurance on the ACA marketplace instead, but they only qualify for the premium tax credits if the plan their employer offers does not meet the (inadequate) coverage and affordability standards. This applies whether or not the employer is covered by the employer mandate. As a result, many primarily lower-income individuals were locked out of marketplace plans that would provide better coverage and, with subsidies, be more affordable. The employer firewall was made worse by the so-called “family glitch”: The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) initially interpreted the law to mean that if employers offered an affordable individual plan for their employees, no one in the employee’s household could qualify for the premium tax credits even if the spouse or family plans offered were not affordable under the same standard. This affected about 5.1 million individuals, about half of whom were children. Most of them (about 85 percent) remained locked in ESI plans that were more expensive and offered poorer coverage than what was available on the ACA marketplace. The employer firewall is one reason why, under the Commonwealth Fund definition, 66 percent of the underinsured have coverage through an ESI.7 The ACA premium tax credits also turned out to be insufficiently generous for many primarily lower-income people, leaving the coverage offered in the marketplace unaffordable. This meant that millions simply went without insurance.

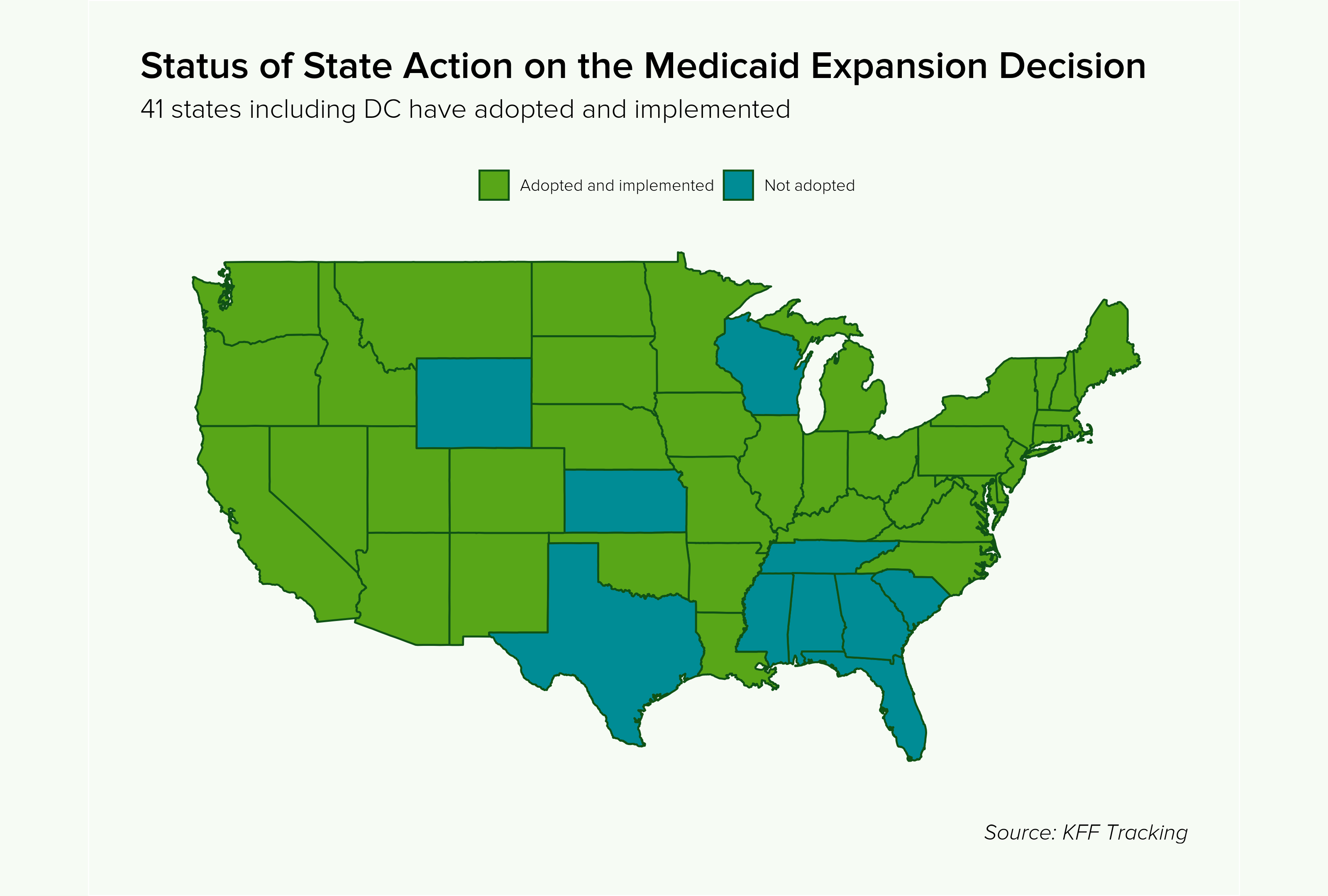

But the larger problems that arose in the wake of the ACA passage were the result of conservative attempts to cripple the law. In 2012, the Supreme Court delivered a serious blow in its National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius decision. Medicaid is administered by the states and jointly funded by the states and federal government. The federal government covers a percentage of total Medicaid fees, called the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP). For the “legacy” Medicaid population, the FMAP is set according to a formula that considers the state’s per-capita income relative to the national average, and ranges from 50 percent to about 77 percent. The ACA, as noted, required that states cover individuals up to 138 percent of the FPL. To defray the additional costs to states, it set the FMAP for the expansion population at 90 percent. In a case subsumed into the Sebelius ruling, Florida (joined by 19 other states) sued the federal government, arguing that it could not impose this requirement and that states could suffer extreme harm if, for example, the federal government ever decided to lower the FMAP (more on this later). The Supreme Court agreed and ruled that the expansion had to be voluntary. In the aftermath of this decision, 21 states decided not to expand Medicaid. While that number has since dwindled, 10 states (holding ~28 percent of the US population) still have not adopted the expansion, and those states are predominantly in the US Southeast (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

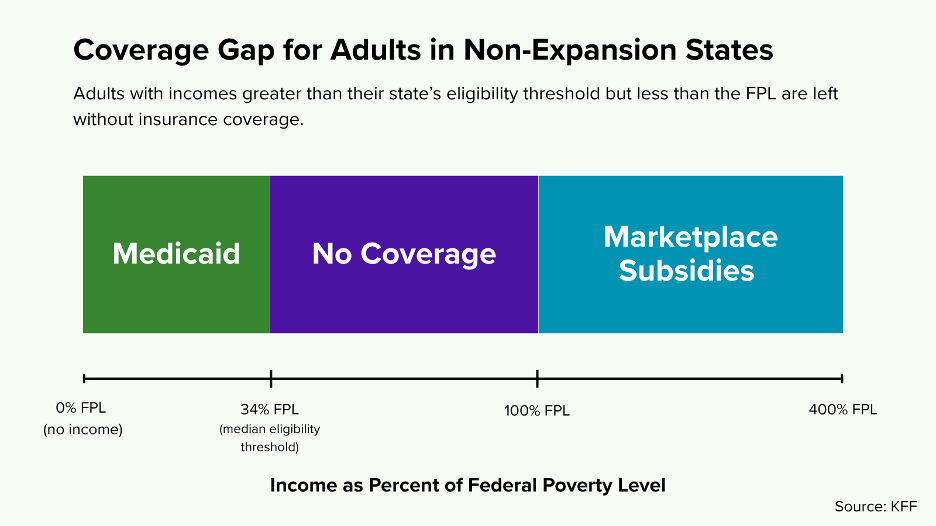

Changing the ACA Medicaid expansion to voluntary generated a host of problems for a system designed around expansion being mandatory. To buy health insurance on the ACA marketplace, one must live in a household with income at or above the FPL. This is because the law was written under the assumption that anyone below the FPL would be covered by Medicaid. The Supreme Court decision thus created an uninsurable population in non-expansion states—those with income too high to qualify for legacy Medicaid and too low to access the ACA marketplace. There are roughly 1.4 million such individuals in this “Medicaid coverage gap,” and 97 percent of them live in the South. Nearly three-quarters of adults in the coverage gap live in just three Southern states: Texas, Florida, and Georgia. Black and Hispanic individuals have suffered disproportionately from this policy dysfunction—among adults in the Medicaid gap, 24 percent are Black and 35 percent are Hispanic. For context, Black people make up about 14 percent of the US population; Hispanic people make up about 19.5 percent of the US population.

Figure 3

Those at 100 percent of the FPL were eligible to access the marketplace, but, as noted, the ACA subsidies were not sufficient to defray costs. Prior to recent Biden administration actions (see Part IV), those between 100 and 133 percent of the FPL were still expected to contribute 2 percent of their annual income toward insurance premiums; those between 133 and 150 percent were expected to contribute roughly 3.5 percent. This represented a significant expenditure for people living at near poverty-levels. As a result, millions more, though technically able to purchase health insurance, found it too expensive to do so. Moreover, even if coverage under an ACA marketplace plan is superior to going without insurance or to the sorts of limited-coverage plans that small employers may offer, it is inferior to Medicaid, which is generally far more comprehensive than private plans and certainly more comprehensive than a bronze tier plan. Thus, even the shift of some individuals from Medicaid to an ACA plan, despite no net change in the number of uninsured, represents an increase in the number of people who are underinsured and exposed to additional, unnecessary financial risk.

Figure 4

III. The Financial Consequences of Medical Debt

The gaps in and limits of existing health insurance coverage mean that when an uninsured or underinsured individual does need to seek medical care, the costs can be enormous. Medical debt can lead to a variety of negative consequences, some more obvious than others. The most obvious and most severe consequence is personal bankruptcy under “Chapter 7” or “Chapter 13” rules. This means liquidating assets and/or setting up a structured payment plan and shutting oneself off from access to credit markets for a period of 7 to 10 years, with extreme damage to one’s credit in the aftermath. Individuals may declare bankruptcy, in part, to stop persistent harassment from debt collectors once their debts have been sold to these organizations after a period of failure to pay. In 2022, medical debt (using the narrow definition) made up an estimated 58 percent of all debts that had gone to collections, and 62 percent of bankruptcies were attributed in part to medical debt.

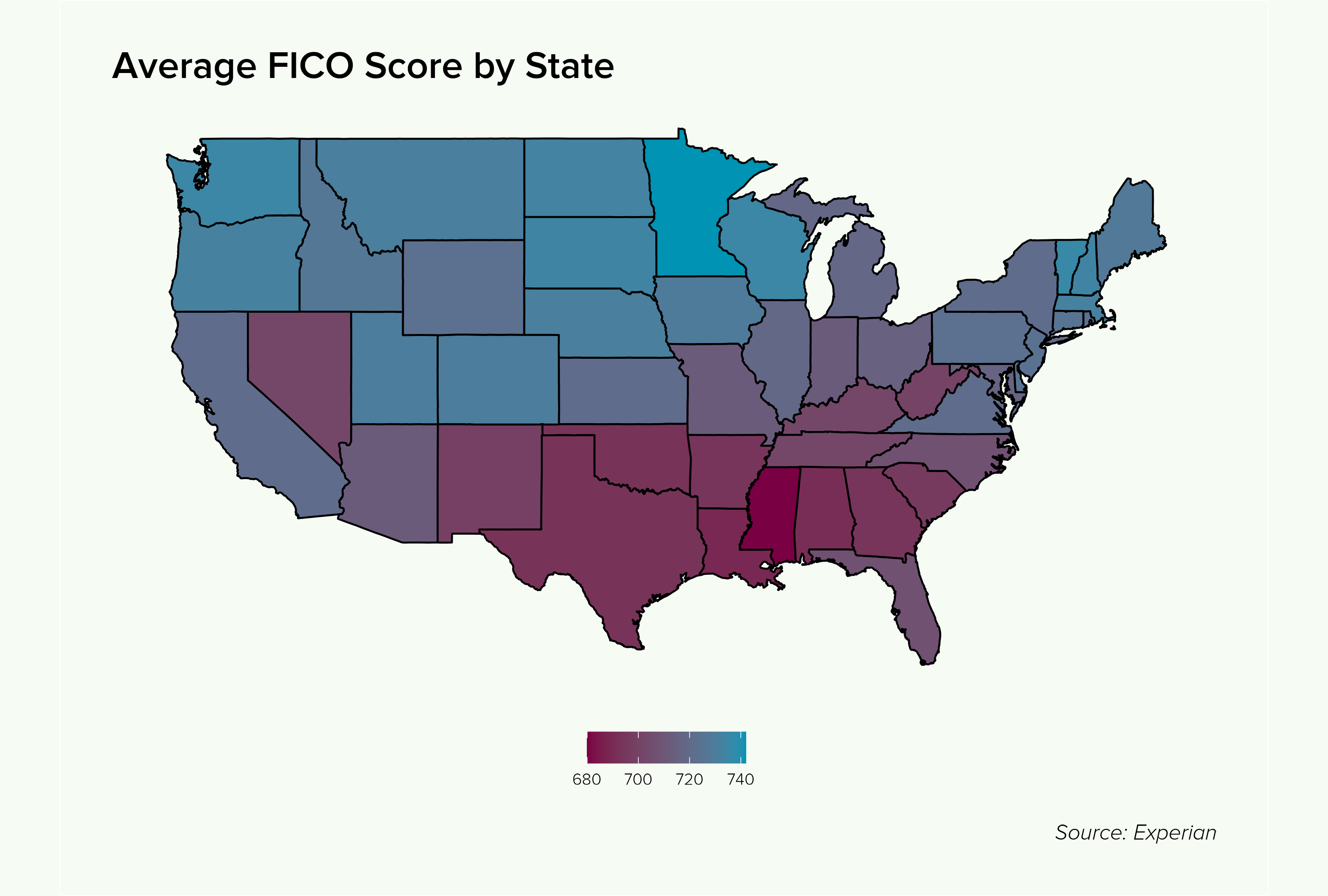

Medical debts can also damage credit scores. Although missed payments or debt in collections do the most damage to one’s credit, a persistent debt load, whether in the form of money owed to a medical service provider, bank, or credit card company, can also hurt one’s credit. While there are other factors at play, a map of FICO (the most widely used and reported credit-scoring algorithm) credit scores by region captures the damage wrought by failure to expand Medicaid in the US Southeast (see Figure 5).

A poor credit score can have a variety of negative impacts on one’s financial well-being. First and most obviously, lenders consider credit score when deciding to whom to lend. A poor credit score means that a family may be unable to obtain a mortgage or a car loan. Credit scores are also commonly used by landlords to screen tenants. As both housing and transportation are key factors in educational and employment opportunities, this can mean reduced income in the short run and reduced economic mobility in the long run.

A poor credit score can also more directly limit employment opportunities when used by employers as part of a background check during the hiring process. A small handful of states and municipalities ban or severely restrict the use of credit checks by employers, but there is no overlap with states that have not expanded Medicaid. These problems also disproportionately affect Black Americans. Black households are not only more likely to carry medical debt than otherwise similar white households but also more likely to hold medical debt that is past due. In fact, in 2015, almost 1 in 3 Black adults between the ages of 18 and 64 had medical debt past due, compared to about 23 percent of white adults.

Figure 5

In less extreme cases, a poorer credit score may lead to less favorable loan terms, including higher interest rates—and that means higher debt service. Negative consequences from debt service (money that must be set aside to make payments to creditors) are common for those carrying medical debt. For those with limited income and assets, debt service may displace spending on food, clothing, and other essentials, leading to material hardship. It can also make savings impossible, stranding individuals with less money for retirement, a down payment on a mortgage, education, or dealing with emergencies—meaning that medical debt can generate more medical debt in another vicious cycle. These impacts on savings and investment may have important implications for the racial wealth gap.

The racial wealth gap describes the difference in assets between white individuals/households and those of otherwise similar (with comparable income, education, etc.) minority individuals/households. Renewed scholarly attention has shed light on the origins and nature of the racial wealth gap, specifically including the legacies of slavery, Jim Crow, mass incarceration, redlining, and other forms of employment, housing, and educational discrimination, among others. Debt, as essentially negative wealth, contributes to the racial wealth gap if held disproportionately according to race. This applies to medical debt.

The Brookings Institution report cited earlier includes an analysis of the impact of medical debt on the Black-white wealth gap. It finds that eliminating medical debt has a “small ameliorating effect” on the racial wealth gap, benefiting Black people the most. This effect is concentrated in households in the bottom 25th percentile of the wealth distribution, because over 80 percent of medical debt is held by individuals in households with zero or negative net worth. The effect is important, though much smaller than that associated with eliminating student debt, another driver of the racial wealth gap. Of course, the Brookings analysis focuses on medical debt, narrowly defined as debt owed to providers, rather than the more expansive definition employed in the KFF analysis. The impact on the racial wealth gap is likely to be much larger when considering all debts that have their origin in medical services.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to disentangle medical debt from other sources of debt—in, for example, credit card balances—using the administrative data available or surveys not designed for that purpose. Such analysis would have to be built on a tailored large-scale survey effort similar to what KFF has done. To my knowledge, there have been no other attempts to do so. Perhaps more importantly though, these sorts of survey analyses have looked solely at a snapshot of current household wealth. Current medical debt is part of household wealth, but past medical debt also contributes to current savings, debt, and assets through the mechanisms described above: resources neither saved nor invested, mortgages not received, higher interest rates paid, education not pursued, and jobs not obtained. A full accounting of the consequences of medical debt—and debt more broadly—for the racial wealth gap would have to account for the damage it does to economic mobility across lifetimes and generations.

IV. Biden Administration Policies Addressing Medical Debt

Medical debt is a problem largely generated by poor policy decisions. It would rapidly disappear if we could extend comprehensive health insurance coverage to the millions of uninsured and underinsured under constant risk of a sudden medical event leading to ruinous financial consequences. Our health-care system, in its Rube Goldberg–like complexity, manages to generate (sometimes good) health insurance coverage for tens of millions, but with numerous holes for the vulnerable to fall through. Despite the seemingly insurmountable challenges, there are actions we can and must take to make the system work better.

Medical debt is a problem largely generated by poor policy decisions. It would rapidly disappear if we could extend comprehensive health insurance coverage to the millions of uninsured and underinsured under constant risk of a sudden medical event leading to ruinous financial consequences.

The Biden administration attempted to combat some of the pernicious effects of medical debt directly through focused research that eventually supported regulatory action by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB). In 2023, the CFPB secured an agreement with the big three Credit Bureaus (Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion) to remove all paid medical debts from credit reports after one year, to remove outstanding medical debts from credit reports until they reach one year, and to remove medical debt in collections from credit reports if the amount is below $500. In early January 2025, the CFPB went further and issued a rule banning the credit bureaus from including medical debt on credit reports at all and prohibiting lenders from considering medical debt in lending decisions. In justifying this decision, the CFPB pointed to research it had conducted a decade earlier showing that medical debt, given the circumstances under which it is accrued, is a poor predictor of ability to repay other types of debts and thus should not be included in assessing lender risk.

If this rule is not prevented from going into effect by the Trump administration, it would remove some of the pernicious knock-on effects of medical debt: in many cases preventing a drop in credit score that limits individuals’ ability to borrow, rent, and obtain employment. Indeed, the CFPB notes that it anticipates an additional 22,000 affordable mortgages per year as a result of this rule. But the rule cannot protect against the negative effects on savings and investment that come with high debt service, it can’t fully insulate against harassment from debt collectors, and it does nothing for individuals who have medical debt in the form of maxed-out credit cards or high-interest bank loans. Only comprehensive health insurance can do that.

Thankfully, the Biden administration also took actions that improved health insurance coverage and quality. For example, in 2022 the IRS issued a new rule finally fixing the “family glitch.” This extended eligibility for premium tax credits and allowed millions of people, primarily women and children, to escape expensive ESI plans and purchase plans on the ACA marketplace that both were cheaper and provided better coverage.

And as part of the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA), the Biden administration implemented another patch to the ACA marketplace. As noted above, individuals who purchase insurance from the marketplace are eligible for premium tax credits meant to defray the costs. But the tax credits were set too low, with those with household incomes between 100 and 150 percent of the FPL still expected to pay between 2 and 4 percent of their income toward the premium. This turned out to be too much for millions of low-income families who made do without. ARPA enhanced the premium tax credits such that the net cost to these families went down to zero. It also increased the tax credits for individuals further up the income distribution and for the first time provided a subsidy for families above 400 percent of the FPL, thus eliminating an abrupt “subsidy cliff” where those just above 400 percent FPL suddenly lost thousands of dollars in support.

These enhanced premium tax credits proved wildly effective at increasing marketplace enrollment and at reducing the number of uninsured and underinsured individuals (see Figure 6). It reduced the number of underinsured individuals, in part, by allowing those already on the marketplace to upgrade to a higher tier of coverage (e.g., from bronze to silver). Insurance enrollment through the marketplace surged from about 11 million individuals in 2020, the last year before the enhanced credits went into effect, to 21.4 million in 2024. At the same time, the number of previously uninsured individuals dropped by about 4 million. This includes about 760,000 Black individuals and 967,000 Hispanic individuals.

Figure 6

Difference in Health Insurance Coverage with and Without Enhanced Premium Tax Credits by Race and Ethnicity, Nationwide and by Medicaid Expansion Status (2025) (Thousands of People)

| Black, Non-Hispanic | Hispanic | White, Non-Hispanic | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Change in Private Nongroup Coverage | ||||

| Nationwide | 1,250 | 1,453 | 4,687 | 485 |

| Expansion States | 309 | 329 | 1,804 | 208 |

| Non-expansion States | 941 | 1,124 | 2,883 | 277 |

Change in Uninsurance | ||||

| Nationwide | -760 | -967 | -2,001 | -242 |

| Expansion States | -198 | -247 | -888 | -117 |

| Non-expansion States | -561 | -720 | -1,112 | -124 |

People across the country benefited, but the effect was much more pronounced in states that did not expand Medicaid. The vast majority of the new marketplace enrollees live in the 10 states that refused to enact the Medicaid expansion. And more than 2.5 million (about 63 percent) of those who gained insurance as a result of the enhanced premium tax credits live in states that did not expand Medicaid. This includes about 74 percent of newly insured Black people and 75 percent of the newly insured Hispanic people. In other words, the enhanced premium tax credits mitigated the damage of the Sebelius decision not to mandate Medicaid expansion. For those between 100 and 138 percent of the FPL, Medicaid coverage would be superior, but affordable coverage through the marketplace still represented a clear improvement over the status quo.

The enhanced credits have only been in effect for 5 years and may not last, so there is not yet any research directly measuring their impact on medical debt. Additionally, medical debt likely accrues over longer periods given the role that low-probability, high-cost medical events play in generating it. Nevertheless, the enhanced premium tax credits, if left in place, will offer additional protection against crippling debt that should appear obvious in the data over time.

V. Trump Administration and Congressional Actions Worsening the Medical Debt Crisis

The Biden administration took actions that both decreased the likelihood of medical debt and buffered against the consequences of it. However, the Trump administration now seems poised to undo these moves and, through cuts to the safety net, expose tens of millions more to financial ruin.

Upon entering the White House, President Trump ordered a freeze of all new regulation, which includes the CFPB rule on medical debt. Last month, the CFPB noted that it will be deprioritizing medical and student debt regulation. The administration laid off 1,400 of the agency’s 1,700 employees as part of the same announcement, so the future of the CFPB and this rule are deeply uncertain.

The enhanced premium tax credits are another area of concern. The tax credits were included in ARPA and then extended until the end of 2025 as part of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA). Both bills were passed under reconciliation, a process that allows Congress to bypass Senate filibusters under certain conditions. Importantly, provisions passed under reconciliation can only be made permanent if they do not increase the budget deficit after a 10-year window. Democrats, dealing with razor-thin legislative margins, were able to use reconciliation to implement a variety of safety net expansions but were not able to assemble the “pay-fors” to make them permanent (see, for example, the sad fate of the ARPA Child Tax Credit expansion). Now, the future of the enhanced premium tax credits looks to be in danger. Republicans have shown little interest in extending them, let alone making them permanent. They have not been discussed as part of the current Republican reconciliation bill negotiations. Making the credits permanent would also require finding $350 billion ($35 billion per year over a 10-year window) in new funding at a time when House Republicans’ reconciliation instructions call for $880 billion in cuts from the committee overseeing Medicaid. Letting the enhanced premium tax credits expire would lead to roughly 4 million people, disproportionately Black and Hispanic, losing their health insurance coverage. Millions more would be forced back into the kinds of inferior coverage that has driven the rise in medical debt, whether through plans offered by small employers or lower-tier, insufficient ACA marketplace plans.

But even this would pale in comparison to the damage that would be done if Congress enacts the severe cuts Republicans are currently contemplating. Republicans have proposed new and extended tax cuts for the wealthy and expanded funding for immigration enforcement and border security. The proposal includes making the temporary provisions from the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) permanent. This alone would require finding $4.5 trillion in “pay-fors” over the next 10 years. And they are planning to do much more than that, which leaves them in a bind. Republicans are currently attempting to use an unprecedented budget gimmick to declare the TCJA “baseline” for budgeting purposes, which would allow them to claim that the $4.5 trillion TCJA extension does not increase the deficit and thus can be made permanent on reconciliation without any further action. But, as part of the reconciliation process, House and Senate committees receive instructions to identify a series of cuts (or, in other cases, increased expenditures) in the programs they oversee to meet a target number—which still leaves over a trillion dollars in cuts that Congress must find to enact its agenda.

The GOP reconciliation package that the Senate and House recently agreed to instructs the House Energy and Commerce Committee to identify $880 billion in savings over the next 10 years. This committee oversees spending on health-care programs including Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). According to Congressional Budget Office estimates, Medicaid outlays account for about 93 percent of the mandatory spending under their jurisdiction (this number excludes Medicare, which the GOP has indicated it will not touch). Budget resolutions passed under reconciliation do not include any instructions or details about how they are to meet their target savings, so we do not know exactly how Medicaid would be affected. But given the scale of the proposed cuts, the GOP mathematically cannot meet its targets without deep cuts to Medicaid. And given their depth and some of the ideas GOP leaders have floated publicly, we know the cuts could be disastrous.

Federal and state governments together spend roughly $880 billion per year on Medicaid, with the federal government covering around $606 billion. If the full cuts are made and if they fall entirely on Medicaid, this would represent a 10 percent cut to yearly Medicaid funding and a 14.5 percent cut to federal Medicaid funding. But the total cuts to Medicaid could be even larger when accounting for potential state responses to federal action. The percentage of Medicaid costs covered by the federal government, the FMAP, varies by state, population, and covered service. If the government withdraws funding for a service or population, a state may follow suit if it is unable to make up the difference: State budgets are several orders of magnitude smaller than the federal budget, and unlike the federal government, states cannot run persistent deficits.

Republicans have floated some specific possible Medicaid cuts. One is to impose work requirements on Medicaid recipients who are able-bodied adults without dependent children. This would save some money precisely because, as previous studies have demonstrated, work requirements are not effective at improving employment outcomes. Republicans, in other words, are counting on people losing their coverage to save money. But the savings they could cobble together from this move alone, roughly $110 billion over 10 years, would not be enough to meet their target. The vast majority, (92 percent) of nondisabled, non-elderly adult Medicaid recipients are working, studying full time, or serving as caregivers. The administrative burden associated with demonstrating compliance, such as filling out forms and meeting deadlines, will almost certainly cause some Medicaid recipients who are already employed to lose their insurance as well—but not at the levels Republicans need.

Thus, they have floated other ideas. These include imposing a hard cap on per-person federal Medicaid spending, requiring all Medicaid recipients above the FPL to “cost share” by paying (larger) premiums or copayments,8 and cutting coverage for certain procedures and “optional” in-home health care and community services that are vital to disabled Medicaid recipients. In effect, they may decide to make Medicaid a poor-quality health insurance plan, one that no longer provides the robust financial protections it currently does. Doing that could render millions of Medicaid recipients underinsured and subject them to the same sort of financial vulnerability millions with private insurance face.

But perhaps most troubling is the “nuclear option” that health-care advocates worry is being considered. One possible way to meet the proposed target would be to “blow up” the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. As noted in Part II, the FMAP for the Medicaid expansion population is 90 percent, while the FMAP for Medicaid’s “legacy” population varies between 50 and 77 percent. If the Republicans eliminated the special FMAP for the expansion population and defaulted it back to the legacy rate (as some are now openly suggesting they will do), it would get them most of the way to their target savings ($625 billion over 10 years). This would trigger a crisis for expansion states. They could either attempt to make up some or all of the difference, or they could end their Medicaid expansions. Indeed, 12 expansion states have so-called “trigger laws” that would require state governments to either end their Medicaid expansions or enact major spending cuts if the FMAP drops below 90 percent. In a worst-case scenario where all states respond by ending their expansion, more than 20 million people would lose their health insurance coverage. Millions of these would fall into the Medicaid gap and immediately become uninsurable. Those above 100 percent of the FPL could attempt to purchase health insurance on the ACA marketplace as they do in current non-expansion states, but they would likely be doing so without the enhanced premium tax credits (which would, in this scenario, cost the government much more than $35 billion per year). The end result would be tens of millions of additional uninsured and underinsured people, a worsening medical debt crisis that will continue to fall disproportionately on Black and Hispanic Americans, and increased health-care costs overall as bankruptcy costs spread throughout the system.9

Conclusion

The medical debt crisis is uniquely American in size and scope, and it’s uniquely American because of policy choices we have and have not made. Medical debt produces material hardship and limits economic mobility. It discourages debtors from seeking out preventive medical care and thus makes catastrophic medical events more likely. And its burden falls disproportionately on the poor and on Black and Hispanic Americans, exacerbating the current and future racial wealth gap.

Medical debt is also bad for creditors. Medical debt constitutes most of the consumer debt that ends up in collections and is implicated in a majority of bankruptcies. When doctors, hospitals, and labs don’t get paid, they attempt to cover their costs by increasing prices for those who can pay. And that means higher health insurance premiums for everyone. Medical debt is one of the ways the US health-care system, relative to that of peer nations, increases overall costs and distributes them more inequitably. It is the result of decades of policy failure and, frankly, sabotage.

Even with efforts by Republican governors and a conservative-majority Supreme Court to sabotage the Medicaid expansion under the ACA, the US has made great strides in extending health insurance to the vast majority of the population. We have not, however, solved the much broader problem of underinsurance. The failure to expand Medicaid in the holdout states has, of course, played a role in the underinsurance problem, as detailed above. But medical debt and underinsurance are issues that extend beyond the 10 holdout states. There are larger problems with the private insurance coverage that most Americans rely on, which can be seen in the distribution of medical debt by age, with those who qualify for Medicare benefiting from protection that those 5 or 10 years younger do not. They can also be seen by comparing the number of underinsured individuals with public versus private insurance coverage.

In the short run, Congress should not slash Medicaid and relegate millions to the coverage gap and millions more to underinsurance through inferior private insurance products. Medicaid is one of our most effective and cost-effective health insurance programs. But fencing off the benefits of health-care policy from economic policy more generally can blind us to the fact that Medicaid is a key weapon against the medical debt crisis. Letting the enhanced premium tax credits expire would be foolish: Millions would become uninsured, and millions more would end up in inferior plans.

In the “medium run,” the federal government should work with the holdout states to expand Medicaid as intended under the ACA. This is not only a moral step to provide millions more Americans with health coverage but also a key piece of ensuring financial viability for health-care providers—especially in disproportionately rural, Black, Hispanic, Native American, and lower-income communities.

In the long run, however, we need to broadly reconsider what constitutes “good” health insurance and how it should be provided. Conservative policy analysts used to note that health insurance was a hybrid product (see footnote 1) and that it could be made cheaper and more accessible by focusing on the “insurance” portion. They thus advocated for high deductible, “catastrophic coverage” plans with lower premiums (often paired with tax-advantaged health savings accounts) and argued that the insured, as educated consumers, would focus expenditures on preventive care and shop around for good deals once they had “skin in the game.” This would further push down costs by reducing demand. There turns out to be multiple problems with this assessment. First, one person’s ordinary cost is another’s catastrophic financial event; a plan with a $5,000 or $10,000 deductible can mean ruinous debts for working- and middle-class households. Second, as noted, people generally don’t have the information they need to be “smart shoppers”—how to compare providers and their quality, how serious that lump or that cough is, or how valuable a procedure might be. When faced with fees at the point of service, they cut back on care indiscriminately,10 and tax-advantaged savings accounts do little to help those who don’t have the disposable income to build up adequate savings. All this means more catastrophic medical events and more debt. Add in the lack of control individuals have about where and when they seek care and the difficulty in determining who is “in-network,” and this market-oriented approach to health insurance falls apart.

Health insurance is not structured like a true insurance policy, and it shouldn’t be, because health-care markets famously do not function well. Health insurance policies available on the ACA marketplace and through major employers may not always be as extreme as the hypothetical ideal conservative plan described here, but they still contribute to the problem of medical debt through high copays and deductibles, narrow and confusing networks, and denied claims. They do this because they are businesses in a poorly functioning market, and this is how they keep their costs down, stay solvent, and turn a modest profit.11 The government, on the other hand, does not need to deny care or pass costs on to the insured because it does not need to turn a profit. And it can keep its costs down by being the biggest (or only) purchaser of care, a status that gives it power to negotiate favorable rates in exchange for being a reliable partner.

There are no free lunches, and there will always be “rationing” in health care, whether it is done through the actions of private insurers or through government and taxpayer choices. But it is clear that our health insurance system for working-aged people, one that covers almost everyone but does so predominately through private market plans, is crippling the vulnerable with debt and raising costs for everyone. And it is specifically the private market component of our system where these problems are at their worst. We could solve this problem through more regulation, through the expansion of public provision, or through both. We could revise the employer mandate to require a silver tier standard of coverage. Or we could rethink the employer mandate more broadly, end the employer firewall, and migrate more people to the ACA marketplace. This could mean better and cheaper coverage for millions as well as the added advantage of more consistent coverage—medical debt frequently emerges during coverage gaps as individuals move between employers or into unemployment. We may also want to do away with the bronze tier on the marketplace altogether as it has proven inadequate to protect so many from crippling debt. We could also consider expanding the regulations that lead to notable differences in claim denial between private Medicare Advantage plans and marketplace or ESI plans, differences that exist even when the same company offers each. Or we could simply look to expand Medicaid and Medicare further by income and by age, since we know these plans already do a much better job of protecting people financially.

A federal effort to ensure more Americans have access to medical care and to protect them from the financial ruin that medical debt can cause may seem fantastical at a time when the Trump administration is planning to take a chainsaw to our public health insurance system. But solving the medical debt crisis is an economic necessity that will require this sort of bold reform.

Footnotes

- As often noted, health insurance is really a hybrid product that is meant to both protect against low-probability/high-cost events (as car, homeowners, and life insurance do) and provide access to continuing and preventive care that, in part, guard against these low-probability/high-cost medical events. ↩︎

- An additional 12 percent had adequate coverage at the time of survey but at least one period without insurance in the previous 12 months. ↩︎

- The researchers defined “significant” as $250 or more. ↩︎

- For example, a person earning $15/hour is far less able to pay a $1,400 deductible than a person earning $150,000/year with a $3,400 deductible on an “inferior” plan. ↩︎

- As noted above, households may also carry medical debt from past periods with no or poor-quality insurance even if they currently have sufficient coverage: A substantial minority of Medicare-eligible Black households nevertheless hold medical debt. ↩︎

- Technically the level is set at 133 percent of the FPL. However, Medicaid includes a 5 percent income disregard, which makes the threshold de facto 138 percent. ↩︎

- About 54 percent of all Americans have coverage through an ESI for some part of the year. ↩︎

- Current Medicaid rules allow some limited cost sharing for recipients in households above 150 percent of the FPL. ↩︎

- For example, researchers estimated that the Medicaid expansion led to a reduction of $5.89 billion in medical debt in collections, roughly 6.7 percent of CFPB’s almost contemporaneous estimate of $88 billion in medical debt in collections. ↩︎

- It also turns out that despite having much lower cost or even no-cost-at-point-of-service, health-care utilization rates are not significantly higher in peer nations. ↩︎

- Health insurers typically have low profit margins on the order of 3–5 percent. If they did not pass costs onto the insured in this manner they likely wouldn’t survive. ↩︎

Suggested Citation

Nuñez, Stephen. 2025. “The US Medical Debt Crisis: Catastrophic Costs of Insufficient Health Coverage,” Roosevelt Institute, May 15, 2025.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Suzanne Kahn, Michael Madowitz, Ira Regmi, Sunny Malhotra, Aastha Uprety, and Katherine De Chant for their feedback, insights, and contributions to this paper. Any errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies are the author’s alone.