What Is the Social Security Act?

August 14, 2025

By Oskar Dye-Furstenberg

On June 8, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced before Congress his intention to create a comprehensive program of social insurance. Following this announcement, the president established an executive Committee on Economic Security (CES) to launch an investigation into the economic security challenges facing the United States. The CES sought to document the acute hardship of the economic depression facing the country and to study established programs of economic redress and social insurance that existed abroad.1 The findings of the committee formed the basis of the Social Security Act (SSA), which was signed into law on August 14, 1935.

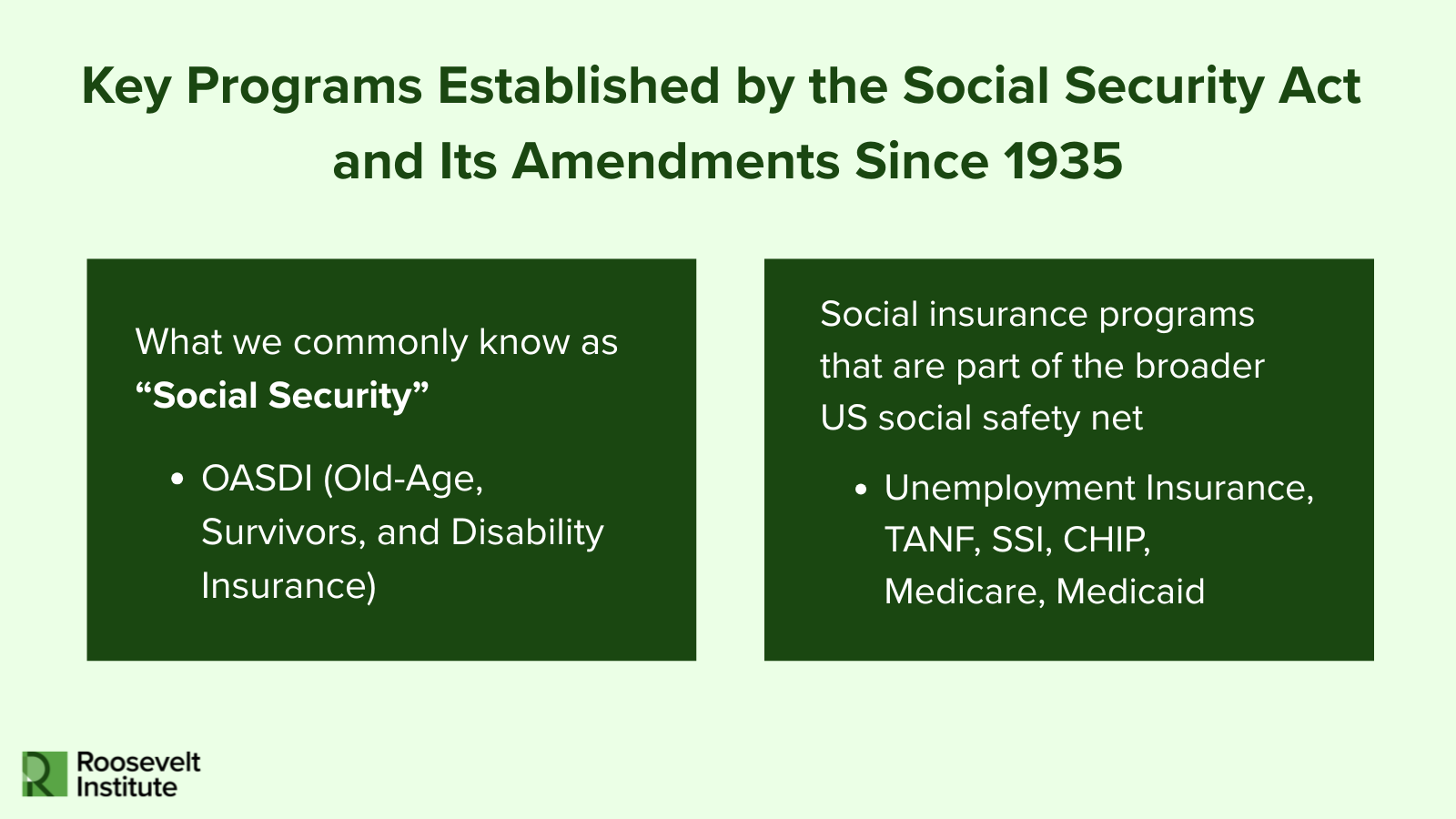

Several key provisions of this bill provided immediate assistance to states for various economic assistance programs.2 These measures form the foundation of our contemporary programs of unemployment insurance and economic welfare assistance. In addition, the SSA established the elements most recognizable as “Social Security benefits”, albeit in a more limited form than the programs in existence today. Specifically, it established

- federal old-age benefits;

- the federal payroll tax to finance Social Security contributions;

- the Old-Age Reserve Account at the Department of Treasury (which would become the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund); and

- the Social Security Board (later renamed Social Security Administration) to administer the Social Security program.

However, the Social Security Act of 1935 fell short of the comprehensive social insurance that some of its originators envisioned. For example, the original act did not establish disability or medical insurance. This was not for lack of consideration. As CES member Isidore S. Falk recounts, the committee had initially considered a program of national health insurance, but the measure was excluded from the original bill over concerns that it would jeopardize the political feasibility of passing the broader social security agenda.

Furthermore, in order to win the votes of Southern congressmembers, legislators wrote several of the act’s provisions to increase state control over the administration of various benefits and to exclude Black workers from benefits. These restrictions limited eligibility for key programs to workers in commerce and industry, which were defined so as to exclude domestic and agricultural laborers. Due to these exclusions, nearly 65 percent of gainfully employed Black workers were excluded from old-age insurance. Other groups not included were officers and crew members of ships, government and nonprofit employees, self-employed persons, and persons already age 65 or older. Because of these exclusions, nearly one-half of the labor force did not receive coverage from the SSA.

Despite its limitations, the SSA would serve, in the words of Labor Secretary and CES member Francis Perkins, as “a sound beginning on which we can build by degrees to our ultimate goal.” Over the 90 years since its signing, lawmakers have amended the SSA numerous times, resulting in various expansions of coverage as well as changes to eligibility and administration. For instance, the program initially limited old-age benefits to workers who had contributed through the payroll tax established by the act. Over time, the scope of the law was broadened to expand the types of coverage provided and to extend benefits to groups beyond workers who had contributed.

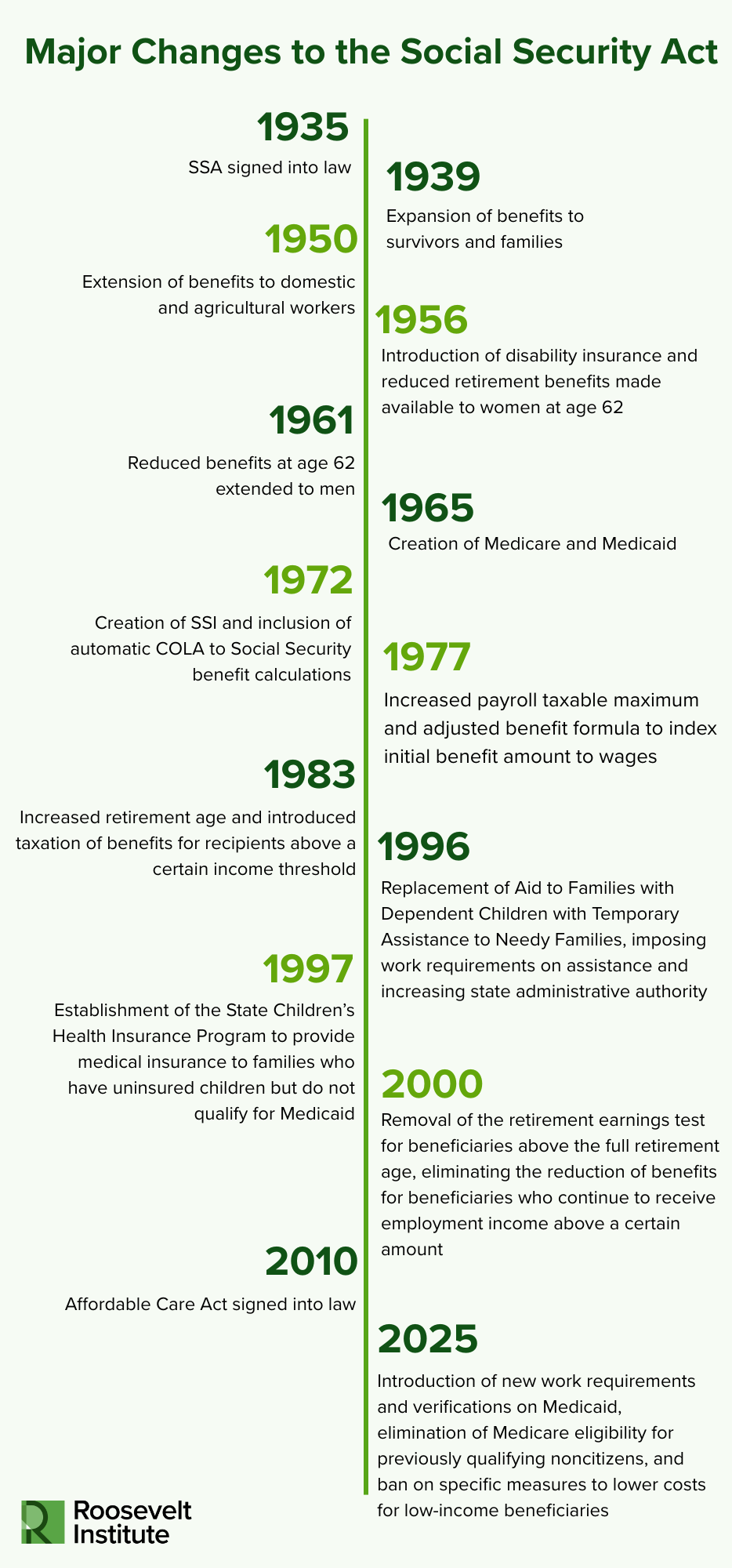

Amendments to the Social Security Act

In 1939, the Social Security Act was amended to include family benefits and survivors insurance. This broadened the scope of economic support to families, in effect recognizing that a single worker’s employment income often provides for more than the individual earner alone. As a result, federal Social Security benefits would encompass a broader notion of social insurance than a narrow focus on individual retirement security. Over time, these benefits were further expanded to include divorced spouses. The 1939 amendment also created the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund, which superseded the original Old-Age Reserve Account established under the Social Security Act of 1935 and which continues to this day.

Further expansions have followed. A 1950 amendment extended old-age insurance coverage to agricultural and domestic workers, beginning to reverse the racial exclusion encoded in the original act. This expansion brought coverage to approximately 850,000 farm workers and 650,000 domestic workers. Further rule changes in 1951, 1954, and 1956 expanded eligibility for millions more and expanded coverage among the self-employed, certain public sector workers, and various other classes of professionals.

In 1956, the law was amended to provide disability benefits,3 rounding out the suite of benefits most generally understood as “social security”: Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI). The 1956 amendments created the Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund, a separate account from the OASI Trust Fund. Disability benefits were restricted to disabled workers between the age of 50 and 64 (this age restriction was lifted by a later amendment to the law) and adults disabled before the age of 18 who were the dependents of retired or deceased insured workers. Additional later amendments expanded disability insurance benefits to dependents, children, spouses, and widow(er)s, and made numerous specific adjustments to eligibility and benefit determinations. While the CES’s initial report had included reference to illness as a source of economic insecurity, this form of coverage was omitted from the original 1935 act due to disagreement over cost and the administrative challenges of determining coverage.

Two amendments in 1965 established the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Title XVIII of the SSA established Medicare to provide medical insurance to the elderly and disabled. The law has since been amended to provide subsidies for private insurance plans that offer expanded forms of coverage. Medicare eligibility is structured along lines generally similar to OASDI, conditioning benefits on payment of payroll taxes or a qualifying disability. The program is administered by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, but enrollment is handled by the Social Security Administration.

Medicaid, on the other hand, is funded by both federal and state governments and provides health insurance to those with low income. While the federal government sets guidelines, states administer the program and determine criteria for eligibility, scope of services, and rates. Originally, through Title XIX of the SSA, Medicaid was restricted to those who were low-income and either a child, disabled adult, or elderly adult that qualified for additional coverage beyond Medicare. Various amendments passed since have expanded eligibility; most significantly, the Affordable Care Act of 2010 included measures expanding Medicaid eligibility to low-income individuals under the age of 65.

The Social Security Amendments of 1972 created the Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program to provide financial assistance to elderly, disabled, or blind persons of limited economic means.4 While the core benefits comprising Social Security insurance are for workers who directly pay into the system through payroll tax and their beneficiaries, SSI introduced a baseline of economic assistance to those who would otherwise fail to qualify. This amendment federalized existing programs administered at the state level (those created by the 1935 SSA), bringing the administration of financial assistance under the purview of the Social Security Administration. Payments from the SSI program come from general government revenues rather than disbursements from the OASI or DI Trust Funds.5

The Social Security Act is the foundation of the social safety net in the United States. The act laid the groundwork for our contemporary systems of unemployment insurance, old-age and disability assistance, economic welfare, and public medical insurance. The act established an active role for the federal government in ensuring the economic well-being and stability of all citizens and their families, remaining to this day one of the most effective and well-regarded government programs.

Read Footnotes

- The intellectual and political precedents for social insurance are broad, ranging from the reforms of German statesman Otto von Bismark to the campaign plans of writer and California gubernatorial candidate Upton Sinclair. The CES’s report included analysis of social insurance programs in countries ranging from western Europe to the USSR to Chile. ↩︎

- These included old-age welfare programs, unemployment benefits, grants for the provision of public-health services, as well as aid to dependent children, to the blind, and for maternal and child health services. ↩︎

- The 1956 amendments also allowed for women to claim reduced retirement benefits at age 62 or full benefits to those who were widows or dependent parents. In 1961, reduced benefits at age 62 were extended to men. ↩︎

- In 1972 Congress also passed a debt extension bill that updated social security benefit calculations so as to include automatic Cost-of-Living-Allowances (COLA), pegging payments to inflation. Prior to this point, benefit increases required legislative authorization. ↩︎

- Other legislative changes of note include: 1977 (increased payroll taxable maximum and adjusted benefit formula to to index initial benefit amount to wages), 1983 (increased the retirement age and introduced taxation of benefits on recipients above a certain income threshold), 1996 (repealed Title IV of the SSA, Aid to Families with Dependent Children, and instituted Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, which imposed work requirements on assistance and increased state administrative authority), 1997 (established the State Children’s Health Insurance Program to provide medical insurance to families with uninsured children but do not qualify for Medicaid), 2000 (eliminated the retirement earnings test for beneficiaries above the full retirement age and eliminated the reduction of benefits for beneficiaries who continue to receive employment income above a certain amount), and 2025 (imposes new work requirements and eligibility verifications on Medicaid, eliminates Medicare eligibility for previously qualifying noncitizens, and bans specific measures to lower costs for low-income beneficiaries). ↩︎