The Neoliberalization of Higher Education: Changes in State Funding and Governance Throughout the 20th Century

September 30, 2025

By Luke Herrine

This is a web-friendly preview of the report.

Report Highlights

Introduction

The Trump administration and its allies are attempting to dismantle much of the US higher education system and place the remainder under the control of right-wing ideologues. Even if they do not realize their greatest ambitions, they have already transformed the landscape of higher education at both the state and federal levels. Reversing these harmful policies will require more than just restoring previously existing programs—the higher education sector will have to be rebuilt. In rebuilding, we will have to revisit the assumptions and institutions around which higher education policy has pivoted for decades.

Many of those assumptions concern the role that the federal government should play in financing higher education. The Roosevelt Institute has argued for a transition away from a system that promotes affordability through subsidy to students—primarily through debt—and toward one that directly funds public colleges, so that they are free for all.1 Much work remains to be done, especially after the whipsawing reworkings of federal student aid during the Biden and Trump administrations.

But a transition to a robust, free public higher education system—and a transition away from the Trump administration’s vision of an academy in which research funds should depend on obedience and ideas inconvenient to the administration are punished—will require grappling with multiple levels of higher education governance and finance. This report and a forthcoming follow-up focus on how public higher education governance has worked at the subnational level. This first installment traces the development of state higher education structures through the 20th century, focusing on how state governments have managed their public colleges as systems and how that management has contributed to various outcomes for students. The next report will focus on how governance decisions at multiple levels have shaped free speech on campus.

When research began on the report, the goal was to be able to develop a static model: to cluster the various state systems into types and draw conclusions about the advantages and disadvantages of each type.2 Unfortunately, despite the presence of some patterns, state systems do not seem to be sortable in a straightforward way—at least, nobody who has looked at the issue has been able to develop an overarching typology. Each state is different from the others, and most have made significant changes over time.

Over the first part of the 20th century, public higher education institutions expanded massively, and states developed bureaucratic planning bodies to ensure they expanded in ways that provided broadly shared benefits. Starting in the late 1970s, however, states began to pick apart these institutions and implement austerity, leading to a more competitive, revenue-focused, and increasingly unequal system that was also more shaped by elected politicians than career bureaucrats.

There is, however, a relatively clear historical pattern to how these institutions have developed over time. Over the first part of the 20th century, public higher education institutions expanded massively, and states developed bureaucratic planning bodies to ensure they expanded in ways that provided broadly shared benefits.3 Starting in the late 1970s, however, states began to pick apart these institutions and implement austerity, leading to a more competitive, revenue-focused, and increasingly unequal system that was also more shaped by elected politicians than career bureaucrats.4

Between roughly 1920 and 1975, state governments were largely committed to expanding access to higher education by expanding funding to public colleges—with the major caveat that different states approached racial and (to a lesser degree) other forms of discrimination quite differently. During this “Growth Era,” nearly all states established independent statewide governing bodies to develop relatively coherent schemes for the allocation of resources and coordination of decisions across colleges. The enormous expansion of higher education in this era was a crucial contributor to the growth in productivity and expansion of a large middle class, as well as the compression of income inequality. But the fact that much of this expansion proceeded whileracial segregation remained law and/or policy in many states meant the color line continued to structure many forms of opportunity. Still, desegregation reduced racial disparities during the latter half of this period.

Under the influence of a new generation of policy thinkers who saw public institutions as lesser versions of capitalist firms, state legislatures began to disempower independent planning commissions, replacing them with efforts to promote market-mediated accountability and with more powerful governors. Meanwhile, universities themselves began to operate more like private firms: diversifying revenue streams, raising tuition, and increasing administrative costs while economizing on faculty. The result was public colleges with less-reliable state subsidies that operated more like their private counterparts.

In the “Neoliberal Era” that followed, this approach to state higher education governance began to fall apart. Under pressure from restive taxpayers and policymakers’ concerns about too large a public sector and too many resources being shared with nonwhite populations, state governments began to cut back on taxes, constraining budgets. Contrary to common belief, per-student funding has not declined overall since the start of this period, but it has become increasingly sensitive to macroeconomic conditions. Under the influence of a new generation of policy thinkers who saw public institutions as lesser versions of capitalist firms, state legislatures began to disempower independent planning commissions, replacing them with efforts to promote market-mediated accountability and with more powerful governors. Meanwhile, universities themselves began to operate more like private firms: diversifying revenue streams, raising tuition, and increasing administrative costs while economizing on faculty. The result was public colleges with less-reliable state subsidies that operated more like their private counterparts. They participated in competitive dynamics that deepened inequality and contributed to slower growth. State flagships increasingly catered to wealthier students, often from out of state, and ill-served the minority of lower-income in-state students who could make it onto campus. Less-elite public institutions lost resources, leaving those students who most benefited from increased investment the least well served and the most in debt—a form of “predatory inclusion.”5

Neither the expansions of the Growth Era nor the retrenchment of the Neoliberal Era proceeded in the same way across all states. In the Neoliberal Era, states with strong tax revolt movements and more powerful Republican parties were more likely to see funding cuts, and for those cuts to be deeper. These differences layered on top of previous variations to produce the variety of institutions we see today.

This historical account provides several lessons for the effort to make higher education more equitable. Looking backward, it spotlights one of many consequences of a federal policy that focuses on promoting affordability through loans and other student-side subsidy: a national market for higher education that erodes state-level efforts to balance equality with excellence, creating cost barriers and inequalities between institutions that increase inequality and reduce access. The relationships between right-wing backlash and the reforms that led to privatization also provide insight into how neoliberalization laid the foundation for the current turn toward censorship, federal control, and student repression. Looking forward, reformers should consider how to create the sorts of governance and funding mechanisms that created more institutional equality during the Growth Era without reproducing their exclusions. Whether that benefit-spreading is done at state or federal level is left open for discussion, but the crucial point is that one must balance excellence with equality within and across institutions to do so at the individual level.

The Basic Structure of State Public Higher Education Systems Today

As used in this report, a “state public higher education system” is a set of institutions that funds and governs public colleges and universities that have been chartered by state governments. There are two basic elements of a state public higher education system: governance and funding.6

Governance

Public colleges are subject to overlapping layers of governance. Their charters, sometimes created by legislation and sometimes by state constitution, lay out their basic structures and modes of decision-making. These charters usually create boards of trustees and/or governors to oversee operations. These boards hire executives and administrators, who oversee the work of faculty. Most universities’ bylaws and some state laws give faculty at least some (and sometimes much) “co-governance” authority, usually focused on academic affairs and hiring and firing colleagues.

Nearly every state also embeds its public colleges into a system, with one or more system-wide institutions to plan and allocate resources across institutions. These systems are our main focus here. The exact responsibilities and structures of these statewide governance institutions vary greatly across states, and states have changed their institutions over time, but they are commonly grouped into three general types:

- A single statewide governing board sets budgets and priorities across all public colleges in the state. Although the exact responsibilities of these boards vary somewhat, they generally operate as corporate boards (replacing the corporate boards of individual campuses), with the power to hire and fire presidents, float bonds, develop bylaws, make final tenure votes, and the like. Eight states have statewide governing boards.

- Single statewide coordinating agencies generally have less power—and different types of power—than governing boards. They operate as intermediaries between campus-level governing boards and state-level elected officials. Usually they have the power to articulate system-wide goals, allocate (some) resources across institutions, administer student aid, and advise governors and legislatures on higher education policy, among other things, while the power to hire and fire presidents and float bonds is left at the campus level. Twenty states currently have single coordinating agencies.

- A higher education administrative agency has even less power. It can generally offer advice, conduct research, and engage in some policy planning but does not have any ability to allocate funds across institutions or write bylaws for them, let alone to engage in direct governance activities such as hiring and firing. Three states have only an administrative agency to facilitate statewide coordination.

Many states do not fit into any of the three above system categories, as they do not have a single body coordinating higher education. Eight states combine administrative agencies with coordinating agencies or governing boards. Eleven states have more than one coordinating agency or governing board—often with one for four-year and another for two-year institutions.7

State elected officials also exercise power over public colleges. They can do so through direct regulation, subject to state and federal constitutional constraints. They can also condition funding—a lever that has mainly been pulled to set performance-based goals (as discussed in Part IV: Shifts in Funding). And they can exercise appointment powers over governance institutions. In most states, the majority of board members on campus-level and/or state-level governance boards are appointed by the governor or the legislature. Some states set statutory or constitutional requirements for regional and/or sectoral representation on these boards. In Alabama, for example, the 12-member commission must include one person from each of the congressional districts in Alabama. Additional members may be appointed from any district, with no more than two from a single district. Ten members are to be appointed by the governor, one by the lieutenant governor, and one by the speaker of the house with the advice and consent of the Senate.8 By contrast, in Nevada—and only in Nevada—board members are directly elected by all eligible voters in the state.9

Federal and local governments also play a role in governing universities, through a combination of conduct regulation and funding conditions. Accrediting agencies allow universities and particular disciplines some degree of self-governance via peer review, with attenuated supervision from the US Department of Education. These institutions will not be a central focus of this report.

Funding

With the exception of some wealthy flagships, public colleges receive most of their funding from their state governments.10 Most of this support is direct and covers general operating expenses, but some of it comes in the form of grants and/or loans to students (and thus makes its way to colleges via tuition charges). Public colleges supplement state support with support from the federal government (both in the form of direct grants, mostly to support research, and in the form of student aid), from students and alumni (and their families), from endowments, and from local governments.11 Different public colleges use very different combinations of these sources of support. Community colleges, for example, are much more likely to receive local government support and much less likely to have endowments than flagships.

States also vary in their “funding model”—that is, the criteria through which the state decides how much money to allocate to each institution in each year. No two states have exactly the same approach, but there are four basic models on which each draws:12

- The most popular is some form of “base-plus” (or “base-adjusted” or “incremental”) funding, in which allocations are determined by adjusting the prior year’s funding allocations by a fixed amount, either across all higher education institutions or by sector (e.g., four-year vs. two-year colleges). Generally, the amount of the adjustment relative to the previous year is not based on any fixed formula or even indexed to changes in cost or enrollment. Rather, it runs mostly on rules of thumb adjusted depending on the amount of pressure the state’s budget is under.

- On the other hand, “input-based” (or “enrollment-based” or “formula”) funding determines allocations based on yearly changes in costs across institutions. The most important input is enrollment, but some formulas also account for characteristics of students (e.g., family income) or other factors that might affect the cost of education.

- Conversely, “performance-based” (or “outcomes-based”) funding adjusts the amount an institution gets based on how close it has come to a series of outcomes, such as degrees awarded, workforce participation, or student credit hours, during the previous year. The idea of this form of funding is to incentivize cost-effective means of getting results rather than allowing costs to grow without supervision. As we will see, this form of funding became important in the Neoliberal Era. It has been repeatedly found to be ineffective at achieving its own goals.

- Finally, “zero-based” (or “institutional requests”) funding is as its name implies: Higher education budgets are renegotiated from scratch each year. This non-formula formula makes allocations highly contingent on the balance of political forces in the state legislature.13

Most states have hybrid systems that combine two or more of these models. A state might, for instance, use a base-plus process as the primary means of allocation and have a performance-based scheme that provides bonuses to colleges that achieve certain outcomes. Or a state might have a base-plus model for four-year colleges and an input-based model for two-year colleges.14

The Current Landscape of Higher Education

During the Neoliberal Era, state governments began to look for ways to make universities more efficient and businesslike. They made funding more variable and contingent, picked apart the bureaucracies they had set up to coordinate university expansions, and encouraged universities to become more reliant on tuition, more competitive, and more financialized. Income inequality took off and student debt levels skyrocketed.

In recent years, higher education politics has taken a darker and even more destabilizing turn. In important ways, this destabilization has been an intensification of neoliberal trends, as it has involved continued budget cuts and transfers of power away from planning boards. But there has also been a newly authoritarian and even nihilistic turn that seeks to undermine even neoliberal versions of universities and their governance systems. At the same time, some states have begun to increase investments and experiment with stronger efforts at affordability.

The intensification of neoliberal trends began with the 2008 financial crisis. As with previous downturns in the Neoliberal Era, it caused state-level budget crises. As with previous downturns, state legislatures used higher education as a balance wheel and cut funding to public institutions. And as with previous downturns, demand for higher education increased and public colleges raised tuition, cut per-student expenditures, or some combination. But this was not the same as previous downturns. Its scale and size were unprecedented in the Neoliberal Era, and the state and university budgets impacted by it had been weakened by years of previous austerity. University funding cuts and tuition increases were the largest yet, and funding did not recover to pre-crisis levels for over a decade.15 The job-market downturn inspired an increase in demand for higher education, pushing many students to enroll in for-profit colleges, which increased debt levels disproportionately among Black and lower-income households.16

Figure 4.

Several states returned to performance-based funding despite over a decade of evidence of failure.17 And the shift of power from independent agencies to governors and deep-pocketed nonprofits accelerated, driven by cuts in staff and funding as well as governors’ efforts to gain greater control.18

The size of the cuts in combination with the impact of the 2008 crisis fueled new narratives of crisis in higher education. The “student debt crisis” quickly became a focus of policy attention, and administrators began to worry about a “demographic cliff” caused by a drop in the birthrate after the 2008 crisis.19 This perspective change played out in a growing movement for expanding funding to higher education and cancelling debt, which began to counter the cost element of neoliberal policies.20 This shift also resulted in skepticism about the value of higher education, most notably pushed by right-wing tech billionaires, as well as advocacy for more radical cost cutting, most notably pushed by education technology or “EdTech” companies. This right-wing skepticism of higher education was joined by an increasingly authoritarian turn in Republican politics.21

Over the past decade, divergent visions of higher education have produced a volatile political field without a clear direction. On the one hand, in the years after the federal government injected extra money to manage COVID-19, funding for higher education recovered to pre-2008 levels in nearly every state and has not yet regressed. On the other hand, the most significant state-level governance reforms have involved some combination of forced reduction of research and teaching programs under extreme financial pressure and measures to prohibit the teaching of subjects that some factions of the Right ideologically object to.22

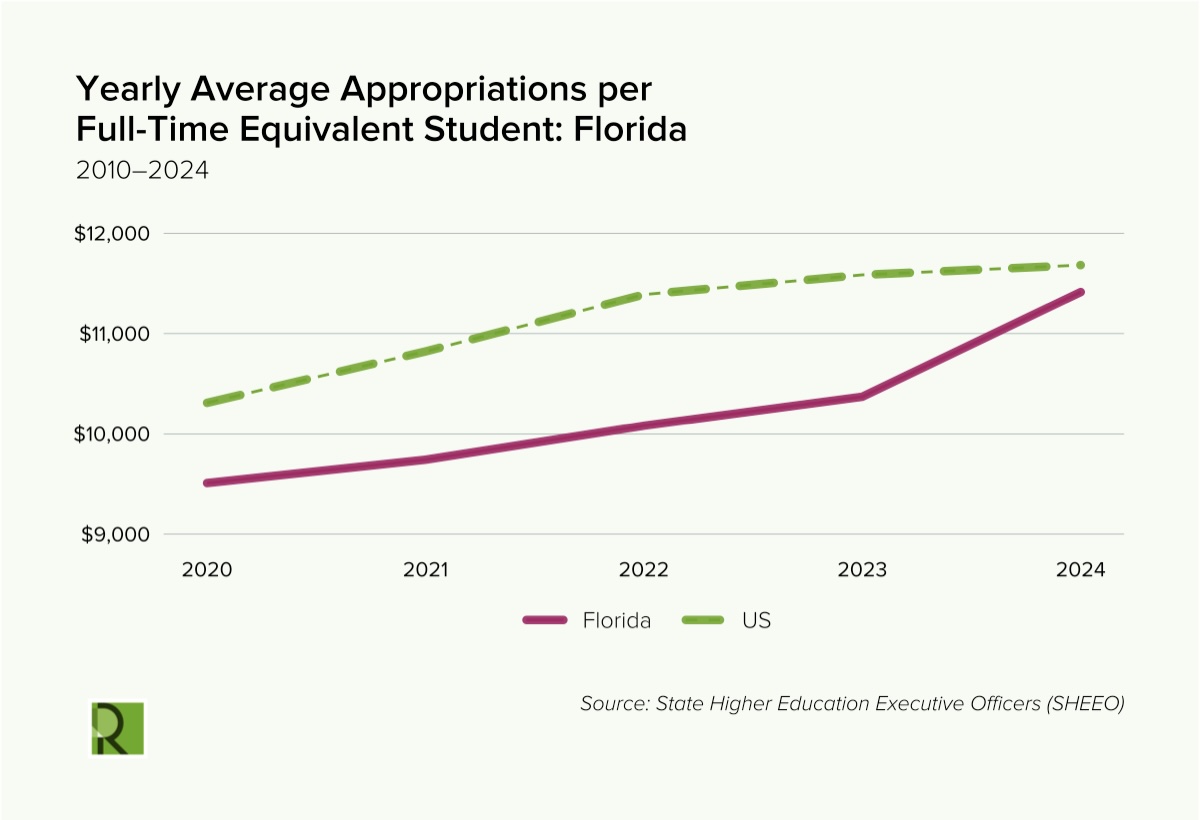

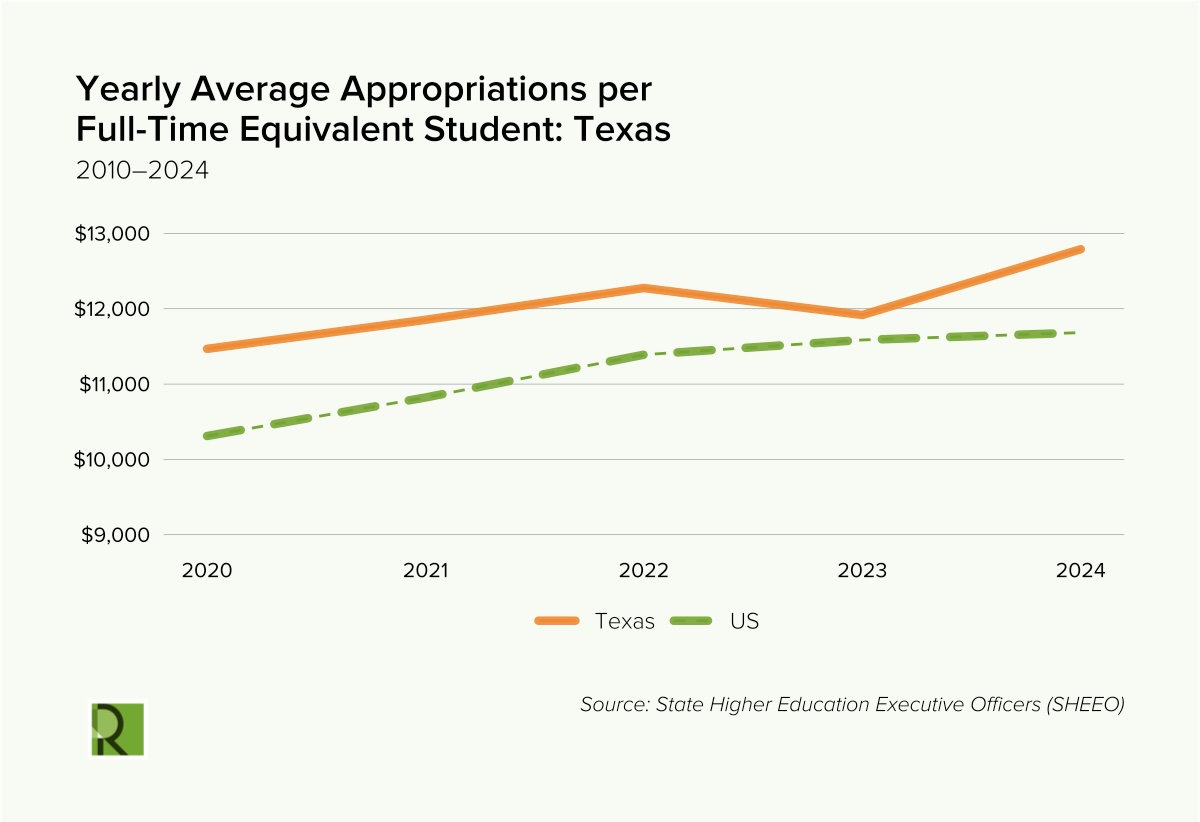

In states like Florida and Texas, these trends coexist: significantly more funding than before 2008 with escalating efforts at authoritarian control.

Despite Increasingly Restrictive Laws, Higher Education Funding Is Rising in Florida and Texas

Florida

Laws passed in Florida:

2021:

- permits students to record lectures without instructor consent

- bars institutions from shielding students from “ideas and opinions that they may find uncomfortable, unwelcome, disagreeable, or offensive”

- mandates annual “Intellectual Freedom and Viewpoint Diversity Assessment” of students, faculty, and administrators

2022:

- bans professors from teaching certain subjects, including institutional racism

- requires public universities to change accreditors after every cycle and conduct post-tenure review every five years

- exempts information on applicants for public state university presidency from public disclosure requirements

2023:

- prohibits general education courses from teaching institutional racism, oppression, or identity politics and bans universities from using state or federal funds on DEI initiatives

- prohibits public employees (including university faculty) from having union dues deducted from their paychecks

- requires educational institutions to discipline students for using bathrooms not corresponding to their assigned sex at birth

2024:

- prohibits higher education teacher training programs from discussing institutional racism, oppression, or identity politics

Texas

Laws passed in Texas:

2023:

- prohibits public colleges and universities from establishing or maintaining DEI offices

- eliminates many tenure protections

2024:

- restructures community college funding to a performance-based model

2025:

- limits expressive activity on college campuses, including a ban on expressive activity between 10 pm and 8 am

- restructures faculty senates, diminishing their power

- requires regular review of general education curriculum by higher education governing board

- creates an ombudsman position, appointed by the governor, to enforce noncompliance with recent higher education legislation

Sources

American Association of University Professors (AAUP), Report of a Special Committee: Political Interference and Academic Freedom in Florida’s Public Higher Education System (AAUP, 2023), https://www.aaup.org/reports-publications/aaup-policies-reports/investigation-and-inquiries/report-special-committee.

Under the second Trump administration, the federal government is attempting to marginalize or eliminate the teaching of facts and analysis it finds distasteful while reducing education subsidy, and state governments do not have a uniform response. A follow-up report will discuss how these efforts relate to past crackdowns and governance regimes.

Key Visualizations

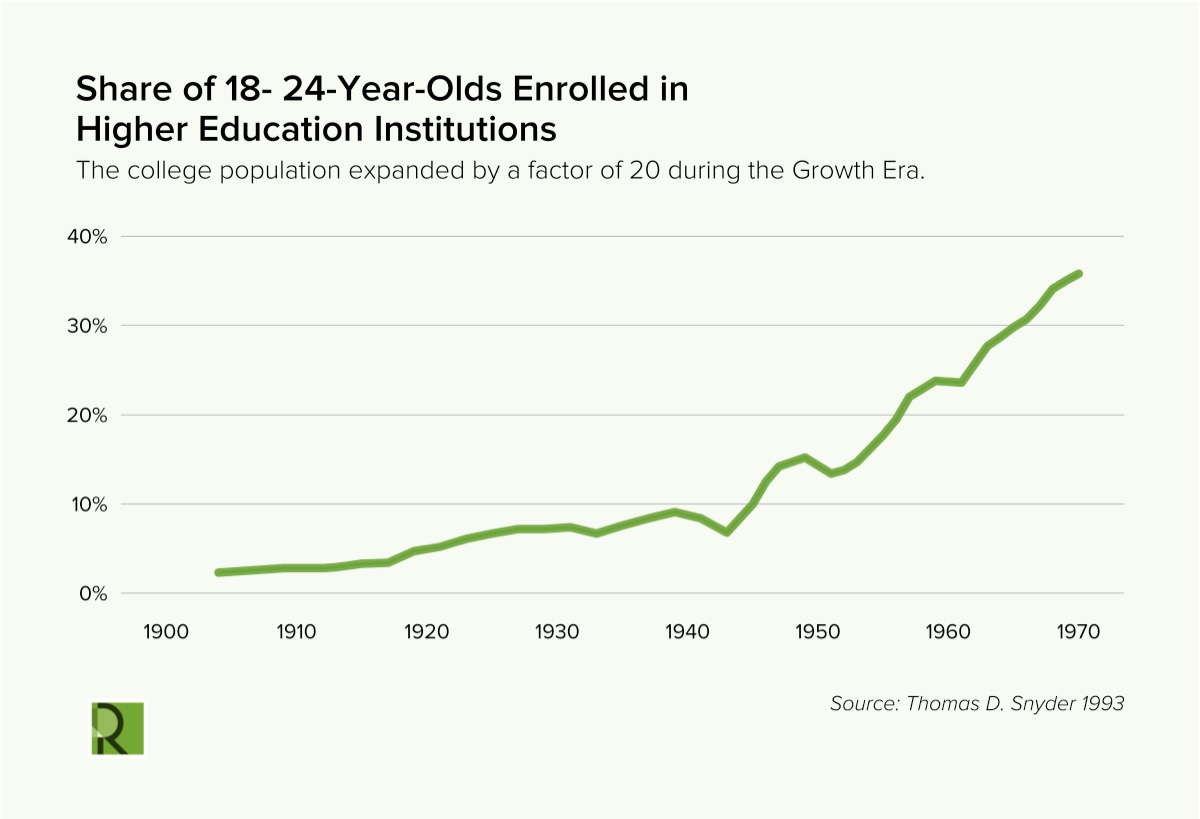

Figure 1. The 20th century saw major gains in college enrollment.

Before 1900, no more than 1 percent of the college-age population (i.e., 18- to 24-year-olds) went to college and only 20 percent of that 1 percent attended public schools.23 That changed dramatically in the 20th century. By 1950, 20 percent of the college-age population attended college. By 1970, 60 percent did. Combined with population growth, the college population expanded by 20 times—from 600,000 to 12 million—between 1900 and 1970. Most of this growth was absorbed by public institutions.24 The fraction of college students at public schools went from roughly 20 percent in 1900 to 50 percent in 1950 to 65 percent in 1970. These institutions went from being, on average, roughly twice as large as private colleges to nearly seven times as large.25

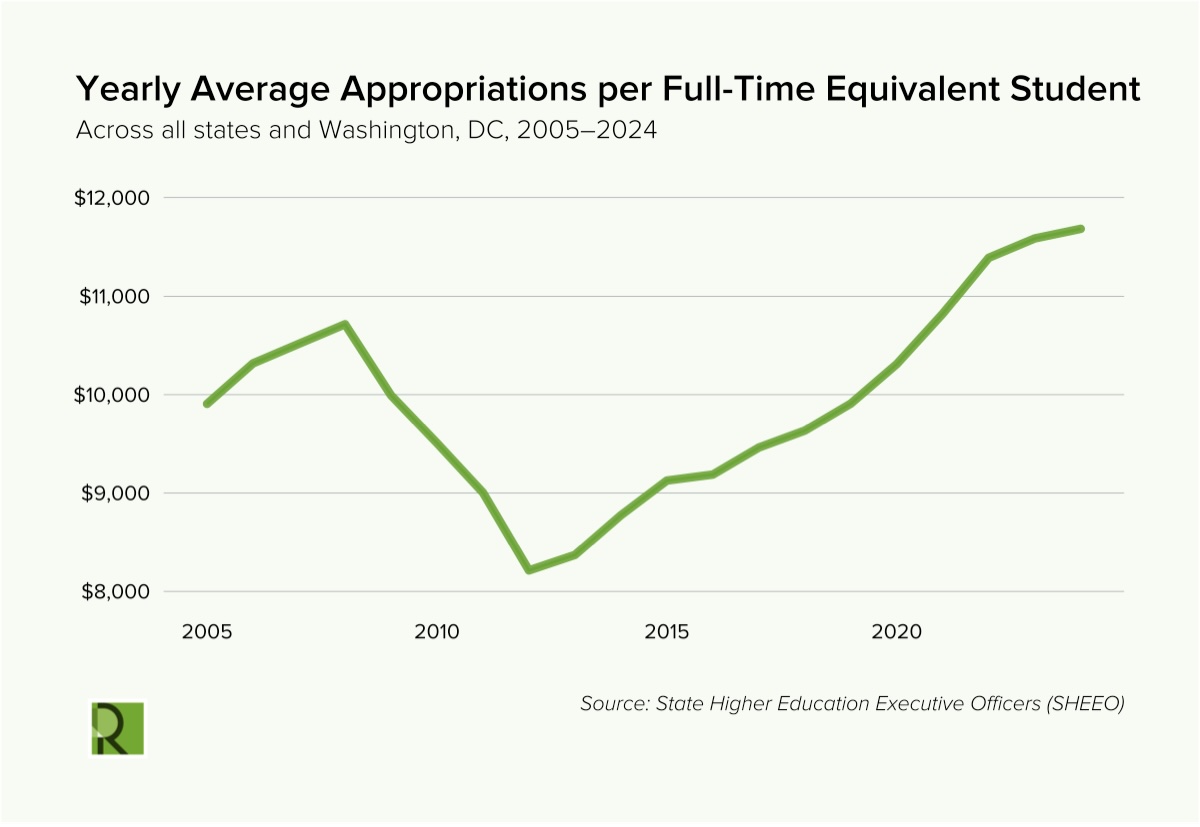

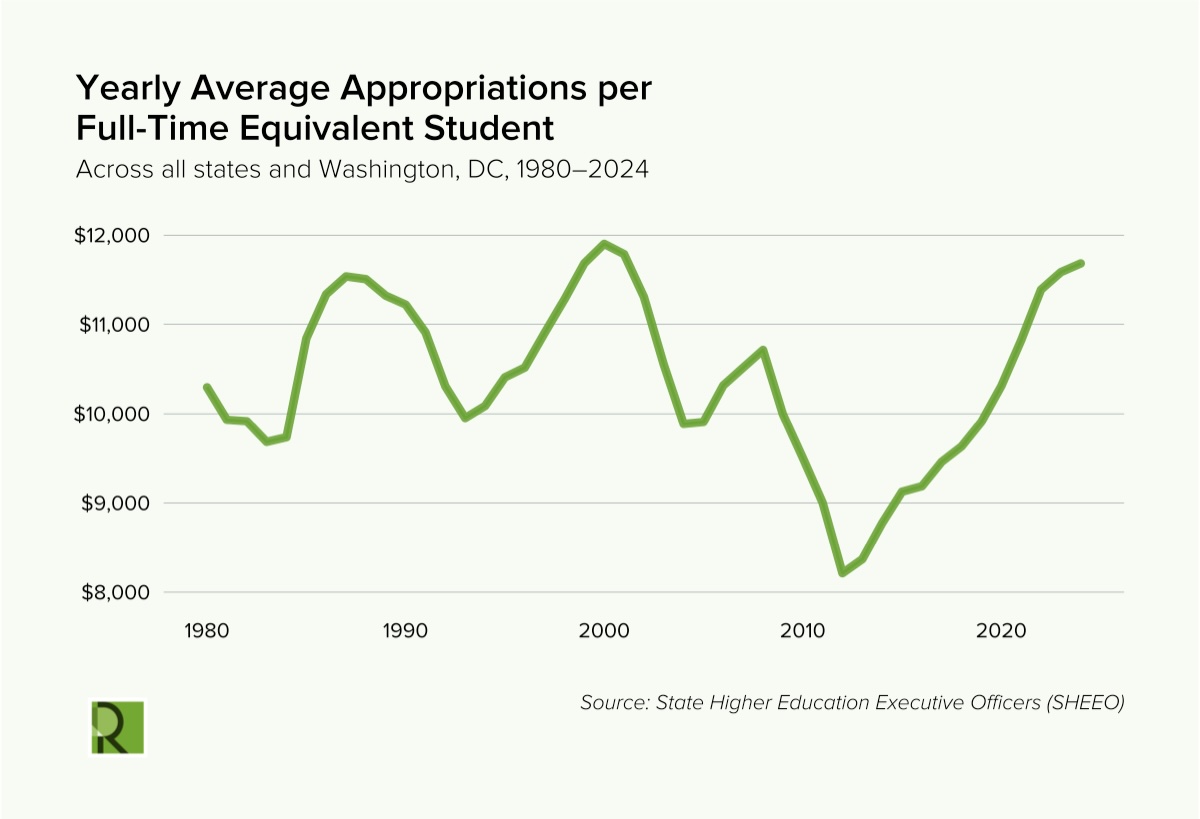

Figure 2. Higher education funding has become sensitive to economic fluctuations.

A graph of the SHEEO’s measure of funding per-FTE averaged across all states and the District of Columbia from 1980 to 2024. The graph does not show a long-term decline. Rather, funding remains more or less constant on average, dipping above and below that average at different points, with an especially deep dip after the 2008 global financial crisis.

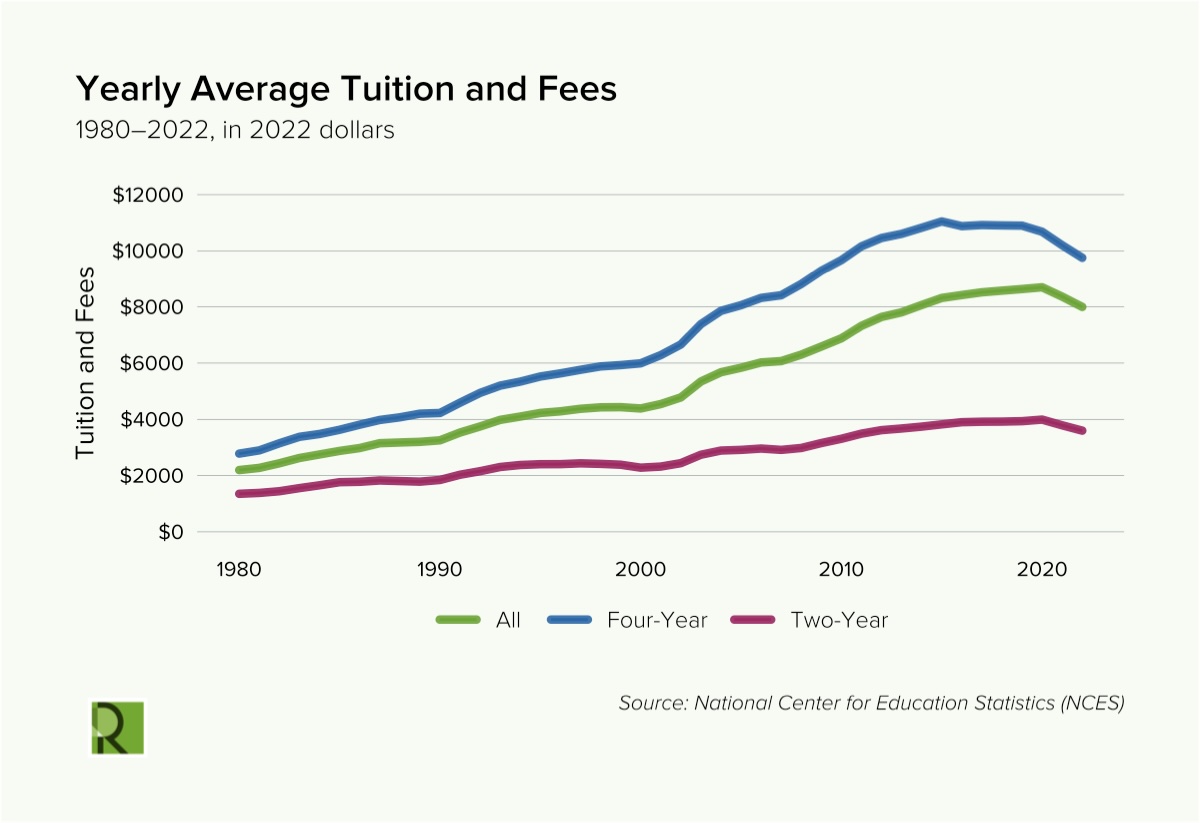

Figure 3. Tuition has skyrocketed.

Average tuition at public colleges (in CPI-adjusted dollars) septupled between 1980 and 2008. It then nearly doubled again between 2008 and 2023, meaning tuition is now more than twelve times as much as it was in 1980.26

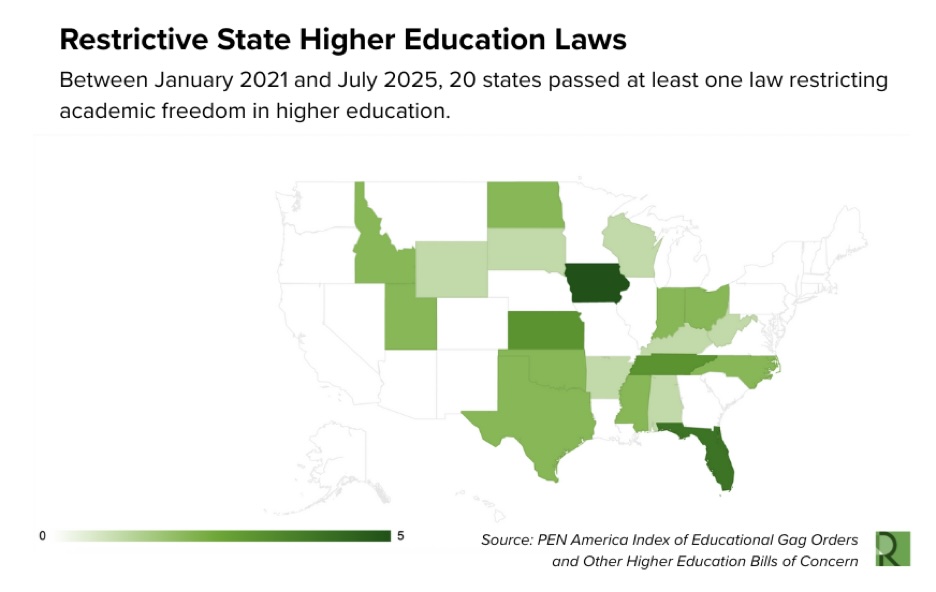

20 States Passed at Least One Higher Education Law Restricting Academic Freedom from 2021–2025

Footnotes

- Suzanne Kahn, More Than Consumers: Post-Neoliberal Identities and Economic Governance, Roosevelt Institute (2022) https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/more-than-consumers; Suzanne Kahn, A Progressive Framework for Free College, Roosevelt Institute (2019) https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/a-progressive-framework-for-free-college; Suzanne Kahn, Jennifer Mittelstadt, and Lisa Levenstein, A True New Deal for Higher Education: How a Stimulus for Higher Ed Can Advance Progressive Policy Goals, Roosevelt Institute (2020) https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/true-new-deal-for-higher-education-stimulus-advance-progressive-policy-goals. ↩︎

- Most of the data and research that this report draws on focuses on the 50 states, although some studies include DC and Puerto Rico. Tribal colleges are not included in our analysis, mainly because information about them is relatively scarce and because tribal governance operates quite differently than state governments (and has a different role in our constitutional order). Generally tribal colleges operate like community colleges—providing two years of relatively practical education (though uniquely designed to pass on native cultures). See generallyJustin P. Guillory and Kelly Ward, “Tribal Colleges and Universities: Identity, Invisibility, and Current Issues,” in Understanding Minority-Serving Institutions, ed. Marybeth Gasman et. al. (SUNY Press, 2008), https://degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/9780791478738-010/html?srsltid=AfmBOorkcuQJpapwM3G7ZgxSmGH1xBfbvGATn2ERrojRA-xPL4kYwxBV. ↩︎

- See Section III: The Growth Era. ↩︎

- See Section IV: The Neoliberal Era. ↩︎

- Louise Seamster and Raphaël Charron-Chénier, “Predatory Inclusion and Education Debt: Rethinking the Racial Wealth Gap,” Social Currents 4, no. 3 (2017), https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2329496516686620. ↩︎

- For charts summarizing the current mix of funding mechanisms and governance systems in higher education institutions in each state, see the following: Table 1 in Sophia Laderman et al., State Approaches to Base Funding for Public Colleges and Universities, SHEEO and NCHEMS (2022), https://sheeo.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/SHEEO_2022_State_Approaches_Base_Funding.pdf#page=22; Education Commission of the States, “Postsecondary Governance Structures 2020,” Education Commission of the States, November 2020. https://reports.ecs.org/comparisons/postsecondary-governance-structures-2020-all. ↩︎

- Mary Fulton, An Analysis of State Postsecondary Governance Structures (Education Commission of the States, 2019), https://ecs.org/wp-content/uploads/An-Analysis-of-State-Postsecondary-Governance-Structures.pdf. ↩︎

- Al. Code § 16-5-2(a). ↩︎

- Paul G. Rubin, “Political appointees vs. elected officials: Examining how the selection mechanism for state governing agency board members influences responsiveness to stakeholders in higher education policy-making,” Education Policy Analysis Archives 29 (2021). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.29.5214. ↩︎

- “Higher Education Expenditures,” Urban Institute, last updated 2024. https://urban.org/policy-centers/cross-center-initiatives/state-and-local-finance-initiative/state-and-local-backgrounders/higher-education-expenditures. ↩︎

- State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO), State Higher Education Finance (SHEEO, 2023), https://shef.sheeo.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/SHEEO_SHEF_FY23_Report.pdf. ↩︎

- Nicholas Hillman, Amberly Dziesinski, and Eunji You, Designing Higher Education Funding Models to Promote Student Success (Student Success Through Applied Research, 2024), https://sstar.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Equity-Funding-Report.pdf. ↩︎

- Sophia Laderman, Dillon McNamara, Brian Prescott, Sarah Torres Lugo, and Dustin Weeden, State Approaches to Base Funding for Public Colleges and Universities (State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, 2022), https://nchems.org/wp-content/uploads/SHEEO_NCHEMS_2022_StateApproaches_BaseFunding.pdf; Kelly Rosinger, Robert Kelchen, Justin Ortagus, Dominique J. Baker, and Mitchell Lingo, Designing state funding formulas for public higher education to center equity (Brookings, 2024), https://brookings.edu/articles/designing-state-funding-formulas-for-public-higher-education-to-center-equity. ↩︎

- For more detail, see Robert Kelchen, Mitchell Lingo, Dominique J. Baker, Kelly Rosinger, Justin Ortagus, and Jiayao Wu, “A Typology and Landscape of State Funding Formulas for Public Colleges and Universities from 2004 to 2021,” The Review of Higher Education 47, no. 3 (2024): 281-314. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2024.a921604. ↩︎

- Laderman, Cummings, Lee, Tandberg, and Weeden, “Higher Education Finance”; Newfield, The Great Mistake. ↩︎

- Cottom, Lower Ed; Charlie Eaton, “Agile predators: private equity and the spread of shareholder value strategies to US for-profit colleges,” Socio-Economic Review 20, no. 2 (2022): 791-815, https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwaa005. ↩︎

- Hillman, “Why Performance-Based.” ↩︎

- McGuinness, State Policy Leadership. ↩︎

- Luke Herrine and Jonathan Glater, “The Student Debt Reset,” California Law Review (forthcoming 2026); Nathan D. Grawe, Demographics and the Demand for Higher Education (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018), https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED598390. ↩︎

- Liebenthal, Burdened; Luke Herrine, “The Law and Political Economy of a Student Debt Jubilee,” Buffalo Law Review 68, no. 2 (2020): 281, https://digitalcommons.law.buffalo.edu/buffalolawreview/vol68/iss2/1; Suzanne Kahn, A Progressive Framework for Free College (Roosevelt Institute, 2019), https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/a-progressive-framework-for-free-college. ↩︎

- See Isaac Kamola, Manufacturing Backlash: Right-Wing Think Tanks and Legislative Attacks on Higher Education, 2021-2023 (AAUP, 2024), https://aaup.org/manufacturing-backlash-right-wing-think-tanks-and-legislative-attacks-higher-education-2021-2023. ↩︎

- Many other states considered, but did not pass, similar measures. For more information, see PEN America’s map of educational gag orders. ↩︎

- Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, “The Shaping of Higher Education: The Formative Years in the United States, 1890-1940,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 13 (1999): 37-62. ↩︎

- Why? Goldin and Katz offer two classes of explanation. First, because public universities started out relatively large and better set up to do (scientific) research, they were better able to adjust to the new scale and scope of higher education in the Twentieth Century. Second, they were cheaper and more inclusive and so better able to absorb a growing population of students with diverse backgrounds. See Claudia Goldin and Lawrence F. Katz, “The Shaping of Higher Education: The Formative Years in the United States, 1890-1940,” Journal of Economic Perspectives 13 (1999): 37-62. https://aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.13.1.37. ↩︎

- Goldin and Katz, “The Shaping of Higher Education”; Thomas D. Snyder, “Higher Education,” in 120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait, ed. Thomas D. Snyder (National Center for Education Statistics, 1993). https://nces.ed.gov/pubs93/93442.pdf. ↩︎

- “Average undergraduate tuition, fees, room, and board rates charged for full-time students in degree-granting postsecondary institutions, by level and control of institution: Selected academic years, 1963-64 through 2022-23,” Digest of Education Statistics, accessed September 2025, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d23/tables/dt23_330.10.asp. ↩︎

Suggested Citation

Herrine, Luke. 2025. The Neoliberalization of Higher Education: Changes in State Funding and Governance Throughout the 20th Century. New York: Roosevelt Institute.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Shahrzad Shams, Suzanne Kahn, Noa Rosinplotz, Aastha Uprety, Katherine De Chant, Dominique Baker, Laura Hamilton, and Marshall Steinbaum for their feedback, insights, and contributions to this paper. Any errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies are the author’s alone.