The Political Economy of the US Media System: Excavating the Roots of the Present Crisis

December 4, 2025

By Bilal Baydoun, Shahrzad Shams, and Victor Pickard

This is a web-friendly preview of the report.

Authors’ Note

As threats to press freedom intensify—from unprecedented attacks on journalists and the gutting of public media to growing concerns about executive power—a fundamental question emerges: How did we get here?

This new Roosevelt Institute report reveals how decades of market-first policymaking has systematically eroded the media’s democratic function, leaving the press structurally vulnerable at precisely the moment when independent journalism matters most. The authors trace a troubling trajectory: consolidation that concentrated power in fewer hands, the abandonment of meaningful public-interest standards, and the rise of platform monopolies with virtually no accountability.

The recent controversy surrounding late-night comedians and the proposed Corporation for Public Broadcasting rescissions aren’t isolated incidents—they’re symptoms of a deeper structural crisis. When commercial imperatives override democratic needs, and when policymakers treat media as just another market rather than essential civic infrastructure, we create a media system susceptible to pressure from all directions.

The stakes couldn’t be higher. American democracy depends on an informed citizenry and a free press capable of holding power accountable. But longstanding policy decisions have created a dangerous convergence: weakened newsrooms, concentrated ownership, and mounting pressure at a time when authoritarian impulses are testing democratic norms worldwide—and at home.

This report maps the political economy behind today’s media crisis and asks the urgent question: What would a media system designed to strengthen democracy actually look like? The analysis provides essential groundwork for anyone ready to reimagine media policy as democracy policy. We must prioritize this because our information infrastructure isn’t optional; it’s core to how a democracy governs itself.

Key Takeaways

- The crisis facing American journalism is the predictable outcome of decades of corporate libertarian media policy that prioritized commercial logics over democracy.

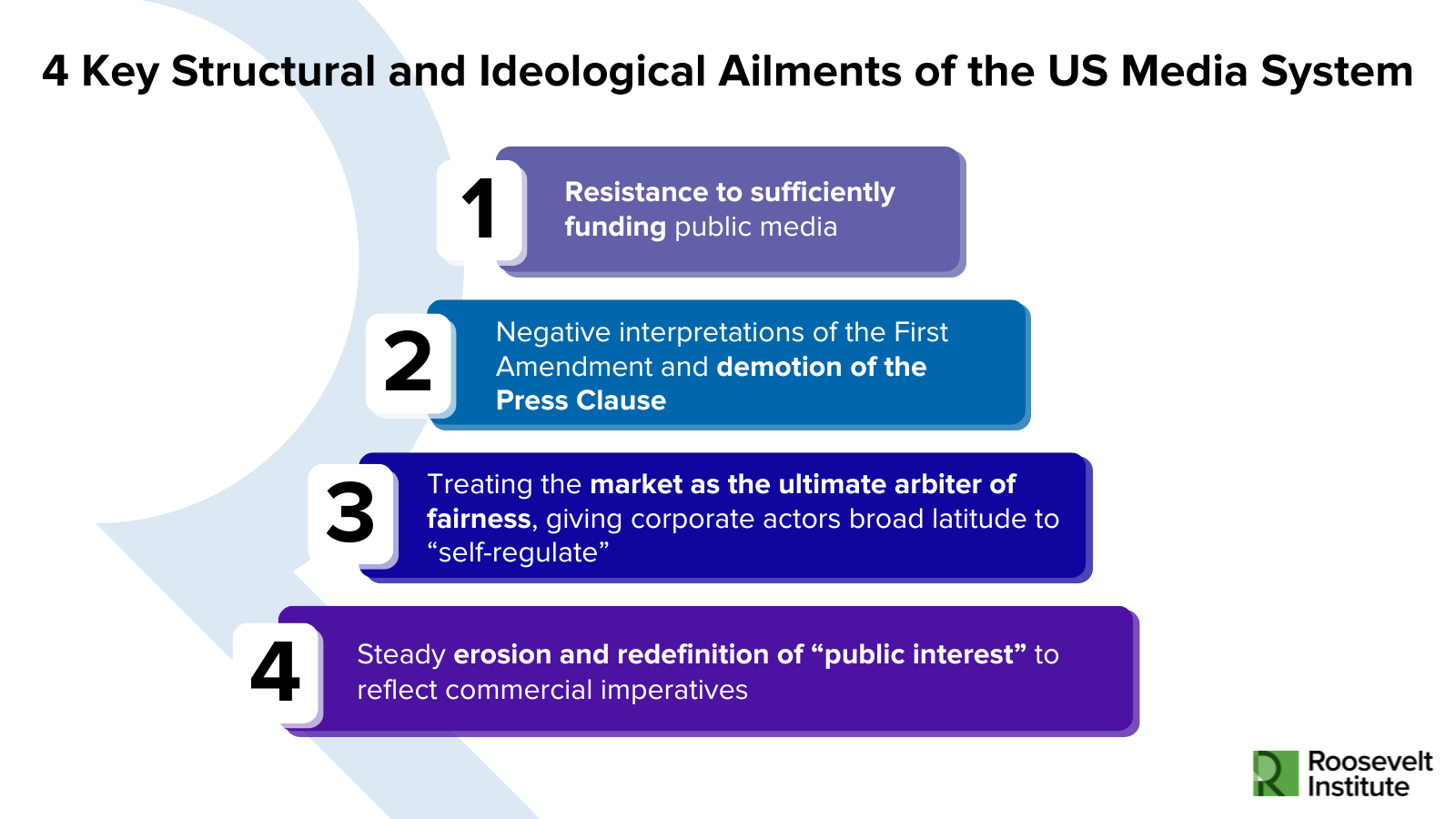

- Four entrenched constraints—the erosion of the public interest, deregulation and self-regulation, chronic underinvestment in public media, and a diminished Press Clause—have structured the often invisible domain of US media policy.

- These constraints have produced cascading harms, including extreme ownership consolidation, a collapse of local news, dependence on dominant digital platforms, and declining public trust.

- A democratic media system is still possible, but it requires a new paradigm of public-interest media policy—one that rebuilds public media and treats journalism as vital democratic infrastructure.

Executive Summary

Multiple crises confront our information and communication systems today, including oligarchic media ownership, the collapse of local journalism, and state threats to media companies. But these are symptomatic of deeper structural pathologies that have long been in the making. Decades of neoliberal thinking about the proper relationships between government, media institutions, the market, and the broader public led to repeated policy failures that have been disastrous for our democracy, as current events so glaringly demonstrate. To begin working toward a new regulatory paradigm and a new public interest–oriented media system, we must make media policy and structural media reform central to a broader pro-democracy movement. But first, we must understand how we arrived at a point where our core media systems and infrastructures are failing democracy so profoundly.

This report traces the roots of the crisis facing our media system and contends that the present moment can only be fully understood by exposing the commercial logics that have been embedded within it from the start. As we show, these commercial imperatives have always constrained the emergence of a truly democratic media order. But the situation deteriorated sharply with the ascent of the neoliberal order, as democratic media policy was steadily eroded by ideological and structural constraints that paved the way for today’s assaults on the media system. We explore four such constraints:

- The steady erosion and redefinition of the “public interest” to reflect commercial imperatives

- A deregulatory agenda that treats the market as the ultimate arbiter of fairness and grants corporate actors broad latitude to “self-regulate”

- Resistance to sufficiently funding public media

- The effective disappearance of the Press Clause, coupled with a negative interpretation of the First Amendment

We next argue that over the course of decades, these four constraints have enabled a range of antidemocratic developments throughout our media system. We point to six specific consequences that have harmed our democratic health, bred by the commercial logics at the core of our media system and turbocharged by its neoliberalization:

- The consolidation of media ownership in the hands of fewer and fewer companies

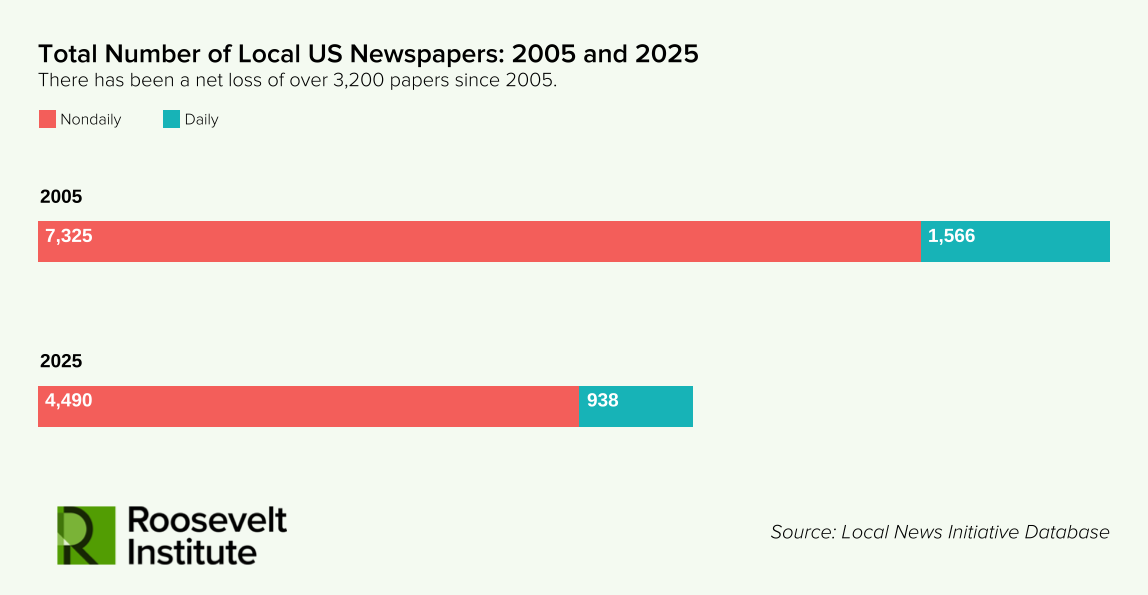

- The accelerating closure of local newspapers and the expansion of news deserts

- Newspapers’ loss of advertising revenue and the consequent widespread layoffs of staff

- The rise of private equity and its deleterious effects on local news

- Platform dominance and the growing dependence of news media on those platforms

- The erosion of public trust in news media, alongside growing trends in news avoidance

Reversing course and building a media and information ecosystem truly compatible with democracy will require a deeper understanding of how we got here, and a commitment to including media policy in a broader democratic reform agenda.

The next chapter of democracy reform must treat our media system as a core infrastructure that makes democracy possible, and thus demands protection from both state control and commercial capture.

Introduction

The idea that democracy requires both an informed citizenry and a free press is foundational to our civic culture. As media and First Amendment scholars often note, the press is the only industry with rights explicitly enshrined in the US Constitution (Minow and Minow 2021; Susca 2024). It can therefore be said that journalism’s true value accrues from its benefits to the polity, rather than the economy. Yet in the US, journalism is primarily a commercial enterprise that treats news and information as commodities. Now, when the commercial viability of journalism looks increasingly bleak, there is no clear path to institutionalizing journalism’s democratic role.

Thus far, the federal government has made only limited attempts to intervene in media policy and bolster journalism. In 2011, during the early stages of the modern journalism crisis, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) released a landmark study on the critical information needs of communities that surveyed the decline of local accountability reporting and how the rise of digital technologies had affected citizens (FCC 2011). Despite a systematic and prescient analysis that warned how a shortage of public interest journalism would lead to “more government waste, more local corruption, less effective schools, and other serious community problems,” the report largely dismissed the possibility of public policy interventions to rescue journalism from market failure, stating that “government is not the main player in this drama” (Pickard 2020). More recently, the Biden administration proposed modest subsidies to support local journalism, but these efforts stalled, reflecting the continued lack of political will to embrace federal interventions that could help revive journalism (Edmonds 2021).

In the midst of this policy failure, the situation has only worsened, for both the commercial viability of journalism and the imperative of an informed citizenry (Metzger 2025). Newspapers continue to downsize or shutter, following a decades-long trend. Large cities that were once served by multiple daily local newspapers now barely sustain one or two major outlets, and have seen dramatic circulation declines and delivery cutbacks (Coddington 2014; P-I Staff and News Services 2006; Guillen 2023; Walsh 2025; Ovshinsky 2008). As a recent report from Muck Rack and Rebuild Local News found, in the early 2000s the US had an average of approximately 40 journalists per 100,000 residents. Today, that figure has decreased by a staggering 75 percent, to just 8.2 full-time journalists. More than 1,000 counties across the country lack the equivalent of a single full-time journalist (Muck Rack and Rebuild Local News 2025).

At the same time, citizens are losing trust in media institutions and retreating from “the news” entirely (Brenan and Saad 2025; Suárez 2024; Associated Press and NORC 2024). Today, just 28 percent of Americans say they trust mass media to report the news “fully, accurately, and fairly”—an all-time low, down from 31 percent in 2024 and 40 percent in 2020 (Brenan 2025). Many Americans are increasingly turning to social media platforms for their news consumption, often encountering unverified or inaccurate information in algorithmic feeds designed to maximize engagement rather than deliver accurate information. This trend is especially pronounced among younger Americans: While 21 percent of all American adults say they regularly get their news from social media influencers, that figure soars to 37 percent for US adults under 30 (Stocking et al. 2024).

A Note on Terminology and the Scope of This Report

We think of the information ecosystem as a kind of democratic infrastructure that includes under its umbrella a range of democratically vital institutions, such as the press and news media, public libraries and knowledge institutions, civic and watchdog organizations, and regulatory bodies. This report is primarily concerned with one of those democratic institutions: the press and the news media system. Of course, communities have critical information needs beyond journalism and news1, and the broader ecosystem of information extends beyond formal institutions and includes everything from government statistics to TikTok reels to generative AI technologies—and the networks and data infrastructure that support the creation and dissemination of information. This wider ecosystem is not a finite thing that can be neatly ordered or controlled. Information is virtually infinite. Similarly, “media” is a sweeping term that can also apply to entertainment, telecommunications policy, and user-generated content. While we acknowledge that truth, our focus in this paper is on the press and news media system, due to its salience to the public’s ability to make informed decisions and meaningfully participate in democracy.

Journalism’s overlapping crises have involved different economic dynamics—among them media consolidation driven by deregulation, newspaper closures accelerated by an overreliance on ever-shrinking advertising revenue, and platform dominance enabled by years of largely unchecked mergers and acquisitions. But these developments share a common ideological foundation: market supremacy. Each aspect of the crisis reflects the same “market knows best” philosophy that treats information as a commodity—rather than a critical piece of our democratic infrastructure—and that trusts private actors to self-regulate.

This laissez-faire approach to our media system has constrained citizens’ “right to know”2 by prioritizing commercial needs over democratic needs. As Stephen Prager (2024) notes,

When profit or perish are the only two available options, most publishers will choose the former no matter what compromises and sacrifices—to the quality of journalism, or to their own employees—they must make to get there . . . The imperative that journalism be profitable is in fundamental conflict with its other functions in a democratic society.

Market supremacy has shrunk both our understanding of what a civic information economy ought to provide in a democracy, and our imagination about how to better guarantee the public access to reliable, diverse information.

More alarming still, our media institutions have become dangerously vulnerable to commercial pressure and political capture. In many outlets, advertisements masquerade as news content, blurring the “church and state” wall between a news organization’s advertising and editorial functions (Pickard 2020). Billionaires can decide which news organizations live or die for mere pennies on the dollar of their fortunes. The billionaire Peter Thiel reportedly provided the financial backing for suits against the media outlet Gawker; the legal attrition from these suits forced the company to declare bankruptcy in 2016 (Mac 2016; Alba 2016). In 2013, then–Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos bought the Washington Post for $250 million in cash—a fraction of the Post’s multibillion-dollar worth in past decades (Mullin and Robertson 2023). Bezos has allegedly dictated what can and can’t be published in the paper’s vaunted opinion page, and notably chose to end its practice of endorsing political candidates (Malone 2025).

When the billionaire Elon Musk acquired Twitter and rebranded it as “X,” he quickly transformed one of the most influential digital news platforms in the world into a vehicle for personal, political, and ideological influence (Thompson 2025). Musk has used the site to promote political misinformation and has reportedly manipulated X’s algorithm to boost his own posts (Fiallo 2025; Thadani, Morse, and Reston 2025; Singh and Dang 2024; Paul 2023). Musk has also called for the imprisonment of CBS’s 60 Minutes journalists (Stetler 2025), and the administration he was once a part of has continued to bar certain journalists from White House briefings, potentially in defiance of a federal court order (Bauder 2025).

The US approach to media governance has been shaped by a conception of freedom defined exclusively as the absence of government involvement. But the sobering reality is that when media organizations cannot withstand commercial pressures, it becomes harder for them to withstand political pressures, too. In our oligarchic age, where billionaires can pledge hundreds of millions of dollars to campaigns and themselves command powerful roles in the government, it can be hard to find the line between state-run media and state-aligned media through private means. As we have seen, the Trump administration has threatened networks with regulatory action to silence what it perceives as unacceptable speech. Recent examples have been CBS’s Stephen Colbert and ABC’s Jimmy Kimmel (Baydoun 2025). Notably, both networks’ parent companies were pursuing major mergers or had other business before the FCC when these threats were issued. As network television becomes less profitable, media conglomerates must consolidate to remain profitable, and this fiduciary responsibility can be easily wielded as political pressure, especially when only a handful of media companies dominate.

Ironically, then, the structure of our laissez-faire media system—touted as a bulwark against the tyranny of state-run media—has not protected against threats from the state. Both public and commercial media outlets today face serious threats from the Trump administration beyond regulatory action alone, as it has pursued lawsuits widely believed to be ideologically motivated against the BBC, CBS, the New York Times, and the Wall Street Journal and defunded the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (Abramsky 2025; Rose and Passantino 2024; Grynbaum 2025; Bose and Stempel 2025; Freking and Jalonick 2025). The administration has launched what amounts to a systematic campaign against press freedom, combining legal harassment, access restrictions, funding cuts, and rhetorical attacks to undermine independent journalism. While Trump himself has long delegitimized the press as “fake news,” the current assault, backed by the power of the federal government and all the resources at its disposal, is an escalation that threatens the institutional foundations of American journalism.

In an era of rampant dis- and misinformation, the consolidated power of a few technology companies over the flow of information, and escalating political attacks on knowledge, public health, and science institutions, we believe it is critical to protect democratically vital information from all its adversaries, whether they come from the White House or the C-suite.3

This report begins from a simple and urgent premise: The next chapter of democracy reform must treat our media system as a core infrastructure that makes democracy possible, and thus demands protection from both state control and commercial capture. Doing so requires a paradigm shift in what the state’s relationship to media ought to be, and what the media’s obligations are to the public. It also requires challenging the myth that the mere act of publicly subsidizing media inevitably devolves into government-controlled media, while an unbridled and poorly regulated commercial media system is immune from capture.

But beginning this new chapter first requires an excavation of “media policy” from the peripheral position it occupies in contemporary debates about democracy preservation. The contours of media policy are nuanced and contested, reflecting the definitional complexity of the word “media” itself (Napoli 2009). As Philip M. Napoli and Robyn Caplan (2016) explain, how we think of “media policy”—and which industries, companies, and technologies we consider as falling within the purview of “media policy”—has critical regulatory and legal implications for the future of journalism, the democratic potential of our information ecosystem, and the prospect of a better-informed citizenry.

This report is meant as a basis for future work that might explore a range of topics related to the US media system and broader information ecosystem. To that end, it maps some of the key ideological and structural conditions that have brought us to the current moment, demonstrating that the present crisis facing our media system is the outcome of decades of neoliberal governance. It then lays the groundwork for future efforts to reimagine and rebuild a media system in service of democracy.

We begin by situating current US media policy within a longer history marked by deregulation and commercial pressures. As this history reveals, our country’s approach to media governance has been constrained by entrenched frameworks and deeply embedded institutional arrangements. Today, these have culminated in a media system largely in tension, if not at odds, with democracy. We then survey some of the damage this approach has inflicted on both the media industry and the public interest. We believe that for future reform efforts to adequately meet the scale of the crisis, we must first understand the structural conditions that produced it.

Footnotes

- Lewis Friedland et al. (2012) identified eight distinct areas in which citizens are entitled to high-quality information: emergencies and risks, health and welfare, education, transportation, economic opportunities, the environment, civic information, and political information. See also Friedland 2023. ↩︎

- The idea that people in a democratic society bear the “right to know” is legally rooted in a positive interpretation of the First Amendment. This view holds that the Constitution guarantees access to reliable, accurate, and comprehensive information—because full political participation demands it. ↩︎

- At the same time, however, we caution against the narrative that the collapse of institutions like local newspapers is part of the inevitable churn of innovation and technology, and that the solution is to simply return to some bygone golden era before the internet. Additionally, although media institutions have come under intense pressure from the current administration, political attacks on the media are not new. The reality is that while certain public triumphs exist in the history of American media and telecommunications policy, information has always been highly gatekept and stratified. What is needed at this historic juncture is not a return to an imagined past but a new, bold vision for a truly democratic information ecosystem. ↩︎

Suggested Citation

Baydoun, Bilal, Shahrzad Shams, and Victor Pickard. 2025. The Political Economy of the US Media System: Excavating the Roots of the Present Crisis. New York: Roosevelt Institute.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Genevieve Lakier, Philip M. Napoli, Suzanne Kahn, Katherine De Chant, Julie Hersh, Toyosi Odusola, and Aastha Uprety for their feedback, insights, and contributions to this paper. Any errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies are the authors’ alone.