“Will Social Security Run Out?” Is the Wrong Question: How Lawmakers Can Protect Beneficiaries and Strengthen OASI

January 15, 2026

By Stephen Nuñez

Introduction

The Social Security Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund reserve is about to become depleted. Seniors worry that the government will not be able to pay them the full benefits they are entitled to. Democratic and Republican politicians alike speak of the need to make hard choices to save Social Security. Young people doubt Social Security will be there for them when they retire.

This is not a prediction about an impending solvency crisis. Rather, this is a description of the United States in 1981. We have been here before. And, quite obviously, the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance program (OASI) did not collapse. It has continued to function well in the time since: Payments are made on time and beneficiaries receive the amounts they are statutorily entitled to. When faced with an impending shortfall, legislators passed a bill in 1981 to provide OASI with bridge funding1 and created a commission to address the long-term health of the program. The National Commission on Social Security Reform (also known as the Greenspan Commission after its chair, Alan Greenspan)—armed with projections from the Social Security Trustees Report—produced recommendations that served as the basis for the 1983 amendments to the Social Security Act. These included a variety of reforms, such as tax increases and a gradual increase in the full-benefit retirement age, that were meant to provide 75 years of fiscal stability.

The 1983 amendments solved the immediate fiscal shortfall and ensured decades of stability. But perceptive readers will notice that 75 years out from 1983 is the year 2058. And yet for the past several years we have heard that Social Security will “go bankrupt” around 2034. Seniors once again worry that the government won’t be able to pay them the full benefits they are entitled to. Democratic and Republican politicians alike once again speak of the need to make hard choices to save Social Security. And young people again doubt Social Security will be there for them when they retire. What changed in the years since the 1983 reforms? And is this really a crisis?

This report describes where we are and how we got here. The actuarial projections upon which the 1983 reforms were based were remarkably accurate. But the actuaries did not (and, indeed, could not) anticipate some aspects of how the economy evolved and fared over the past few decades. Specifically, they did not assume growing income inequality or the insufficient fiscal response to the unexpectedly deep Great Recession. And those “unexpected economic developments,” as they’re called in actuarial lingo, turned out to have major implications for the Social Security Trust Fund reserve. So we will find ourselves at a crossroads for the OASI program sooner than expected. And we will once again have to make “hard choices” about taxes and benefits going forward.

But this is not a crisis that calls into question the viability of OASI. As in 1983, legislators can institute reforms that will ensure the fiscal health of the program for another 75 years, or in perpetuity. In fact, they could have done so at any point in the past two decades (at considerably less cost); the actuaries recognized the divergence from their initial projections and accounted for it long ago. When Congress does act, it will be armed with decades of new data on the relationship between the structure of the economy and the OASI program and will have a host of options to close the fiscal shortfall and secure the Social Security Trust Fund against future unanticipated developments. The question is not whether we can fix Social Security, but rather who will bear the costs when we do.

When Congress does act, it will be armed with decades of new data on the relationship between the structure of the economy and the OASI program and will have a host of options to close the fiscal shortfall and secure the Social Security Trust Fund against future unanticipated developments. The question is not whether we can fix Social Security, but rather who will bear the costs when we do.

This report first provides an overview of the OASI program, how it is funded, and how the Social Security Administration is legally obligated to treat its revenue and benefit payments. It then turns to the 1983 amendments to the Social Security Act and the actuarial projections that underlie them: What did they get right, and what could they not anticipate? This forms the basis for a discussion in the subsequent section of lessons policymakers can draw from the US economic experience over the past four decades. Armed with these recommendations, the report finally turns to the impending Trust Fund reserve depletion and discusses how this can be remedied, who would bear the costs of given options, and what legislators can do to protect Social Security from future unanticipated developments.

Social Security Basics

OASI provides monthly benefits to retired workers and their family members or, in the case of death, to their surviving eligible family members (“survivors”).2 OASI evolved out of the “Old Age Insurance” program created in 1935 as part of the Social Security Act. OASI is funded entirely through a payroll tax set by the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA).3 That tax is currently set at 5.3 percent of gross income for employees, with employers expected to contribute an additional 5.3 percent.4 The payroll tax is applied to covered earnings up to the FICA payroll tax cap (the “taxable maximum”). The cap itself grows each year in response to growth in average national wages. In 2026 it was set at $184,500.

In contrast to how it is sometimes described, OASI is not a defined contributions pension program. Individuals do not receive benefits based directly on how much they pay into the program or based on how well this “investment” does. OASI is, rather, a “pay-go” program. This means that tax revenue taken in from current payroll tax payers is immediately used to cover the cost of benefits to those currently receiving OASI. OASI benefits are instead calculated using each worker’s average indexed monthly earnings (AIME).

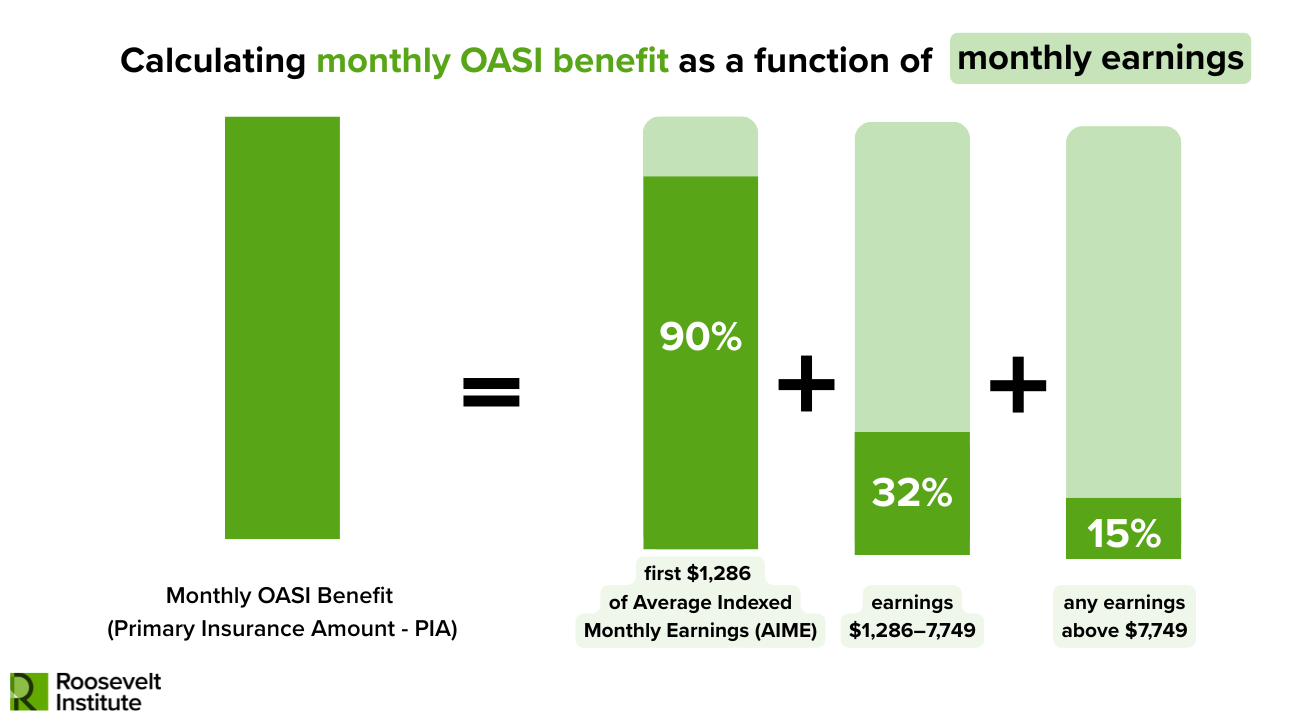

AIME is a measure of the average earnings of the worker over an (up to) 35-year period, adjusted (indexed) to reflect changes to overall average wage level in the economy during that period. It captures both inflation and real growth in average wages in each year. The Social Security Administration (SSA) averages up to 35 years with the highest indexed wages for each worker (AIME) and then applies a formula to calculate the primary insurance amount (PIA), which is the benefit an individual will receive if they retire at the “normal retirement age” as set by law. Individuals who elect to receive benefits earlier or later than their designated “normal retirement age” have their monthly benefits adjusted down or up respectively. The PIA formula employs “bend points” similar to tax brackets, which are adjusted yearly. The first chunk of an individual’s AIME (set in 2025 to $1,226) is multiplied by 0.9, the next (set in 2025 between $1,227 and $7,391) is multiplied by 0.32, and then anything above this is multiplied by by 0.15. These three numbers are then summed to produce the PIA. As a result of this formula, OASI is (modestly) progressive, paid for mostly through a flat tax. Individuals who earn more during their highest earnings years will receive a larger monthly benefit, but as they cross through the PIA bend points, the impact of additional earnings subject to tax on future benefits is reduced (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

As noted, OASI is funded largely through payroll taxes.5 When annual revenue is greater than benefits paid out, the Social Security Administration is legally required to invest the excess in interest-bearing Treasury securities. When investments mature, the resulting payout is immediately reinvested in new Treasury securities. These assets constitute the Social Security Trust Fund “reserve.”

The Social Security Administration is legally prohibited from borrowing to cover expenses or from accessing general tax revenue to pay out benefits. If benefits obligations are greater than tax revenue, the SSA may draw on the Trust Fund reserve (by redeeming bonds) to cover the difference. If there are no reserves, it is not clear what the SSA would or could do, because this would lead to conflicting legal obligations under federal law. However, the administration might, for example, choose to slash benefits payments across the board or pay full benefits on a delayed schedule.

When people talk of Social Security “going bankrupt,” they are (incorrectly or misleadingly) referring to a scenario where the Social Security Trust Fund has no reserves (it has become “depleted”) and tax revenue is insufficient to cover existing benefits obligations. Due to demographic changes and unexpected economic developments (see below), Social Security benefit obligations have been larger than tax revenue for about 15 years now. The SSA has been drawing on its (substantial) reserves during this time to cover the difference. The SSA has long estimated that its reserves will be depleted somewhere around 2033–35, at which point it estimates that tax revenue will cover roughly 80 percent of benefits obligations. In the unprecedented absence of congressional intervention, Social Security would not “go bankrupt” but would be required to cut or delay benefits because, as noted, it is legally prohibited under current law from borrowing or accessing other sources of revenue. But there is no reason to expect this will happen, as Congress still has time to act to avoid Trust Fund reserve depletion. As in 1981, Congress could temporarily authorize the SSA to borrow from another fund or give it access to other tax revenue to meet its obligations while it works on a long-term solution. Trust Fund reserve depletion, were it to occur, is thus not an emergency—but it will require legislative action. The country will have to make important decisions about the future of Social Security: how it is funded, how generous it will be, and when it can be accessed.

To guide these decisions, it is important to first ask why the country is at this point more than 20 years ahead of expectations and to consider what lessons we can draw from the causes. To answer those questions, we now turn to the 1983 Social Security amendments.

The Social Security Reform Act of 1983

In 1983, the Greenspan Commission issued its final report on recommended reforms to ensure that Social Security would remain solvent for the next 75 years. The recommended reforms included a package of cost-cutting (e.g., gradually raising the retirement age for future cohorts of beneficiaries) and revenue-generating (e.g., increases to the FICA payroll tax rate) options that in combination would close the fiscal shortfall over this period, according to the 1983 Social Security Trustees Report, an annual report laying out projections under differing scenarios produced by and with consultation from the Office of the Chief Actuary at the SSA. These recommendations served as the basis of the Social Security Reform Act of 1983. The specific combination of reforms included in the act was the product of the political landscape at the time: a Republican president, a Democratic House of Representatives, and a Republican Senate. It might have looked somewhat different with, for example, different margins in the House or Senate (e.g., more focus on revenue generation vs. cost-cutting). But their options were, nevertheless, constrained both by the existing shortfall and by the looming demographic shifts that these reforms were meant to address.

As noted, Social Security is a “pay-go” system, so current workers’ tax payments cover current recipients’ benefits. Thus the change in the ratio of workers to beneficiaries is an important consideration in projecting the fiscal status of a program and the tax rates and other programmatic features necessary to cover obligations. The SSA in 1983 was well aware that the baby boomers (1946–64) were an unusually large cohort, that they would one day begin to retire, and that future (smaller) cohorts of workers would have to cover their OASI benefits. And their demographic predictions, which underlie the proposed reforms, proved to be remarkably accurate. The SSA also accurately predicted fertility rates and their rate of decline, increases in longevity, population (inclusive of immigration), and age distribution over the past decades. So why then did the reforms backed by these projections not produce the anticipated 756 years of fiscal stability? The answer lies in two major economic developments that the SSA did not anticipate.

Earnings Inequality

As noted, the FICA payroll tax that funds Social Security includes a cap beyond which additional earnings are no longer subject to the tax. That cap is automatically adjusted upward each year according to a formula put into place as part of a series of reforms in the 1970s. In 1983, 90 percent of all Social Security eligible earnings (included in benefits determination) fell below the existing payroll tax cap. The actuarial projections that served as a guide to lawmakers drafting the 1983 reforms included an assumption that this percentage would remain roughly constant over the following 75-year period. Separately, they included assumptions about the average real (in excess of inflation) earnings growth over the next 75 years. Both assumptions informed the reforms to taxes and benefits included in 1983 amendments because they defined the expected tax base.

The predictions about the average annual earnings growth proved to be quite accurate. However, while average real earnings grew as anticipated, the distribution of gains was unexpectedly unequal. And this had implications for the percentage of earnings captured by the payroll tax. The top roughly 6 percent of earners continued to earn above the payroll tax cap as anticipated. But their real earnings grew by an unexpectedly large average of 62 percent from 1983 through 2000. The remaining 94 percent of workers whose earnings were entirely below the payroll tax cap saw average real earnings gains of only 17 percent during the same period.

Figure 2.

This unanticipated earnings inequality (even as average earnings grew according to projections) meant that the FICA payroll tax cap did not rise quickly enough to maintain the assumed 90 percent tax coverage. As a result, the share of earnings subject to the FICA payroll tax dropped from 90 percent in 1983 to roughly 82.5 percent in 2000, where it stabilized (with some fluctuations according to the business cycle from then on). The sluggish earnings gains for those below the payroll tax cap did mean that these workers would eventually receive lower than anticipated OASI payments when they retired, reducing Trust Fund benefits obligations. But this effect was dwarfed by the massive decades-long loss in tax revenue (and interest payments) for the SSA at a time when the Trust Fund was supposed to be building its reserve (as discussed below).

This was the first major “hit” to the financial health of the Social Security Trust Fund. The next arrived in the form of the Great Recession.

The Great Recession and the Long Recovery

The SSA’s projections do not include assumptions about the business cycle beyond a short window of a few years. Over a 75-year period there will, however, be periods of sluggish economic growth and recessions. The longer-term assumptions are designed to reflect average or smoothed growth, with periods of slow and fast growth offsetting each other. The 1983 reforms were sufficient to allow the Social Security Trust Fund to weather these events safely. Events like the 1990–91 recession or the “Dot-com Bust” did not seriously affect the SSA’s finances.

The Great Recession, however, was a rare and deep economic contraction with an extraordinarily slow and extended recovery. Nothing like it had happened since prior to the passage of the Social Security Act, when modern fiscal and monetary policy had not yet taken root. And the SSA did not and could not assume an event like this would occur.

When the economy contracts, a few things happen that affect the Social Security Trust Fund. Individuals become unemployed for longer spells or drop out of the workforce entirely, cutting tax revenue. Worker earnings growth slows, further cutting tax revenue. And some older workers opt for early retirement, increasing benefits expenditures. As the Great Recession was particularly deep, each of these effects was larger than usual and thus did more damage to the Trust Fund than an “ordinary” recession would have. The response to a recession from the Federal Reserve (monetary policy) and Congress (fiscal policy) can help the economy recover quickly and return to trend. But this did not happen after the Great Recession. The fiscal and monetary response proved sufficient to pull the economy out of recession fairly quickly but left the economy quite weak. It took unexpectedly long to return to full employment, and that sluggish growth exacerbated the problem.

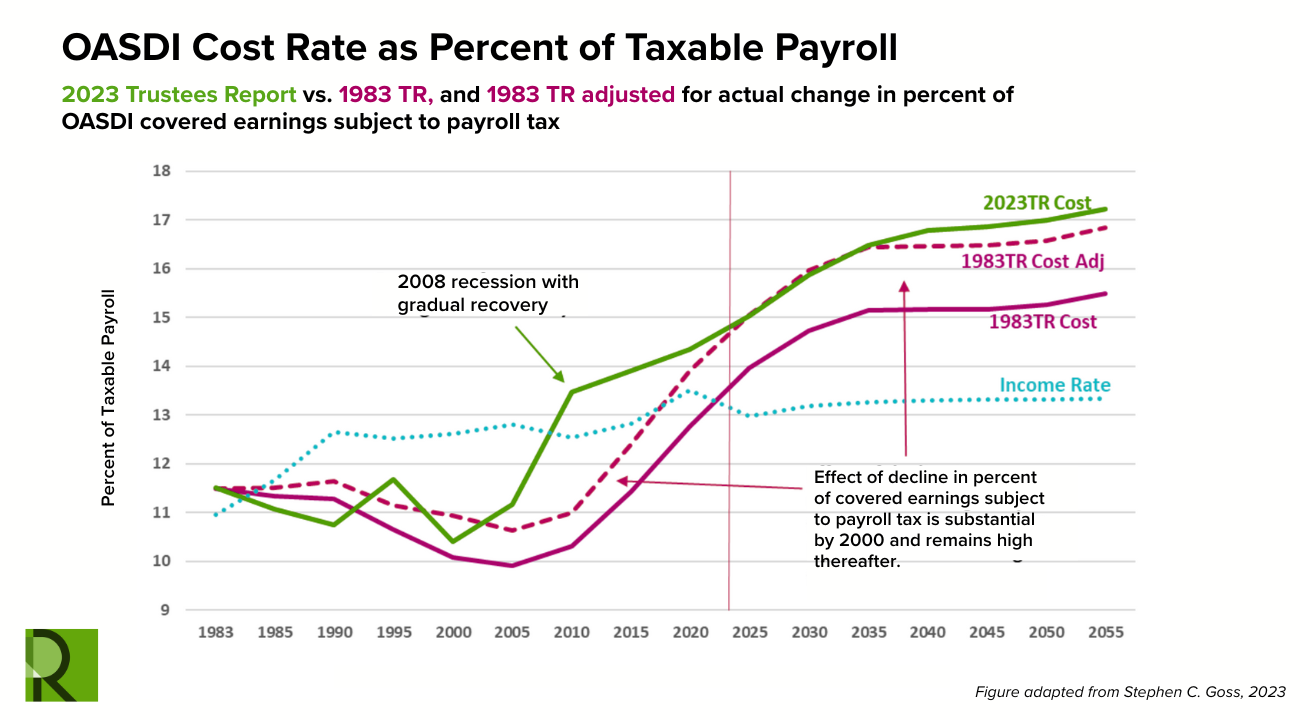

Figure 3

Figure 3 is a recreation of a graph the Office of the Chief Actuary produced to visualize the impact of unexpected earnings inequality and the Great Recession and subsequent wan recovery on the Trust Fund over time. For ease of comparison, y-axis values are presented as a percent of taxable payroll. The solid magenta line represents the original cost projections that underlie the 1983 Social Security amendments. The dashed magenta line is the cost adjusted for decline in the percent of earnings subject to the payroll tax.7 The green line represents actual costs looking backward and projected costs looking forward (as of 2023) and further incorporates the impact of the Great Recession and the gradual recovery. And the dotted blue line represents the income rate (i.e., the incoming tax revenue).8

When the cost lines are below the “income rate” line, the Social Security Trust Fund is taking in more tax revenue than it is paying out in benefits. Thus the Trust Fund reserve is growing. When the cost lines cross above the income rate line, the Social Security Trust Fund is paying out more in benefits than it is taking in in tax revenue and is drawing down its reserve.

The solid magenta line on the graph demonstrates that, in the absence of the unexpected income inequality and the Great Recession, the Social Security Trust fund would have begun drawing down its reserves sometime around 2021–22. This was anticipated and is the product of known demographic shifts (e.g., baby boomers retiring). If projections in 1983 had been correct, the Trust Fund would have begun drawing down reserves at this point and would have continued to do so until they were depleted in 2063, when the program would have to be revisited. As noted, the 1983 reforms were never meant to produce a positive reserve in perpetuity.

But the combination of the Great Recession and growing earnings inequality meant that the SSA had to begin drawing down its reserves much sooner than anticipated. Instead of hitting that point in 2021–22, it hit this point in roughly 2009, as shown by the green line. This meant the Trust Fund reserve was smaller than anticipated because it had fewer years to grow and collect interest before being drawn upon. You can see this impact in estimated time to reserve fund depletion: Had it “fully matured” until 2021–22, it would have been sufficient to cover the tax shortfall for about 40 years (to 2063); instead, the reserve that had accumulated by 2009 is only sufficient to cover the tax shortfall for about 25 years (to roughly 2034).

As a matter of accounting math and assuming no legislative action until the reserve is quite close to depletion, the gap between benefits obligations and tax revenue over the 75-year period starting in roughly 2034 will require increasing tax revenue by at least one-third, decreasing benefits obligations by at least one-quarter, or some combination of revenue-generation and cost-reduction that can provide the equivalent. This is not unsolvable, but it will require legislative action, particularly if we are to continue providing Social Security benefits at their scheduled levels.

This is not unsolvable, but it will require legislative action, particularly if we are to continue providing Social Security benefits at their scheduled levels.

We can draw useful lessons from decades since Congress last reformed Social Security as we consider our options to close the shortfall, though; we understand much more about how the economy works and the ways in which it may shift than we did in 1983. This gives us the opportunity to explore, for example, new sources of revenue. But it also illustrates the need to prepare for unexpected events that may scuttle even the best plans. Relatedly, there are lessons to draw from the lack of legislative action until the reserve is close to depletion. If legislators had acted upon the information presented in Figure 3 decades ago, the amount of revenue-generation (e.g., tax increases) or cost-reduction (e.g., benefits cuts) necessary to close the fiscal shortfall could have been considerably smaller, and they may not have had to revisit program finances for quite some time. Accounting for politicians’ unwillingness to touch the “third rail” of American politics until forced by circumstances also lends itself to some changes in approach going forward.

What Have We Learned Since 1983?

Fiscal Stimulus and Macroeconomic Policy

Economic fluctuations and their subsequent political response are much harder to predict than demographic changes. But the strength of the economy and, in particular, the job market is just as crucial to the health of OASI. This is true to some extent of all government policies, but a few factors set Social Security apart. The first is that a weak job market induces retirement, decreasing tax revenue and increasing the near-term cost of the program. It is true that recessions and stagnant growth increase the rolls for programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) as well. But when the economy recovers, the number of SNAP beneficiaries drops. While it’s possible to “unretire,” it is not particularly common; therefore, every new OASI beneficiary represents an earlier-than-expected stream of long-term costs.

The second is that, unlike other programs, OASI almost entirely depends on (pro-cyclical) payroll tax revenue (past and present) to cover costs. When a recession happens, the government as a whole can go into the red, borrowing to cover for reduced tax revenues (and, indeed, to increase spending to stimulate the economy). But the SSA cannot do this under current law. In this sense it is similar to a state government, dependent on the federal government to get the economy running again to restore its tax base. State governments can, however, also benefit from more direct assistance from the federal government in the form of grants and loans. Think, for example, of the various programs created or kept afloat through funding from the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. Social Security has never received support through any such fiscal stimulus package.

If legislators are unwilling to spend funds from a fiscal stimulus package directly on support for the OASI fund when necessary (which it may not be for less severe economic downturns), they should at least keep the health of the fund in mind when crafting the package. Immediate negative consequences come from insufficient fiscal stimulus in the wake of a recession. But, as we have seen, this also creates longer-term problems for our public pension system.

The FICA Tax Cap

Had earnings gains been more evenly distributed above and below the payroll tax cap (producing the same average earnings growth overall) and in the absence of the Great Recession, the Trust Fund reserve would have grown as anticipated and would have covered the gap between tax revenue and benefits payments until 2063 as planned. We can speculate as to why this discrepancy occurred (e.g., the continuing decline in share of labor compensation in GDP and a broader decline in union representation and worker power during this period), but, regardless, this starved the SSA of crucial revenue at a time when it had intended to be building the Trust Fund reserve for future use.

That said, it is not clear how valuable it is, from a policy perspective, to focus on a world where earnings gains were more equal rather than on the FICA cap itself. If the tax cap had been designed to grow quickly enough to continue collecting taxes on 90 percent of eligible earnings (and in the absence of the Great Recession), the Trust Fund reserve would have grown much closer to what was anticipated and would have avoided depletion until much closer to 2063, as planned.9 For accounting purposes, it doesn’t particularly matter whether the revenue comes mainly from middle-class or wealthier earners.

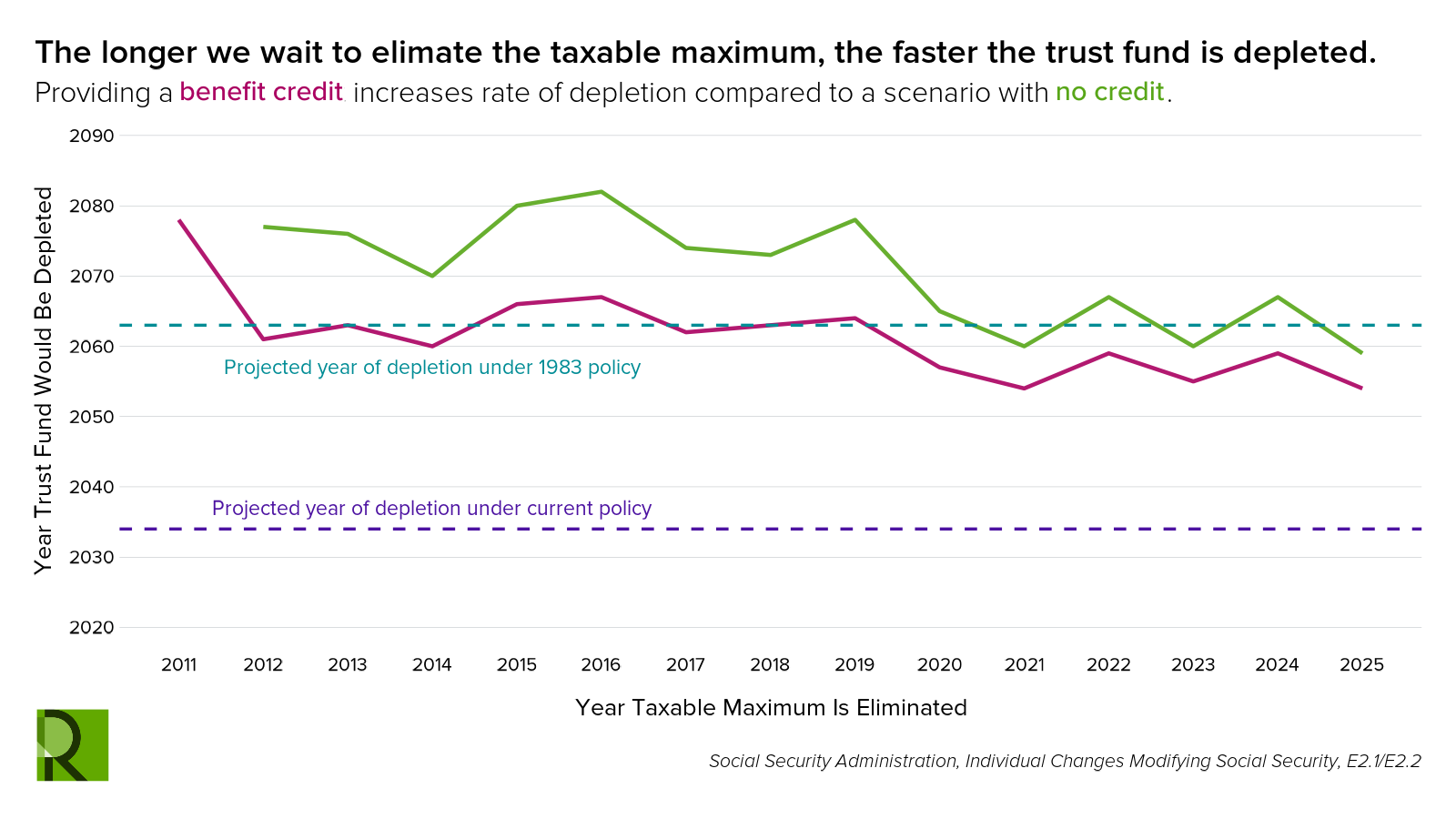

It has long been common for scholars and advocates on the Left to call for abolishing the FICA payroll tax cap entirely as a way to fix Social Security’s finances. Indeed, if there had been no cap after 1983 or if legislators had removed the cap 5 to 10 years ago,10 the Trust Fund reserve would likely have carried us to 2063 (or beyond); the SSA only needed to collect taxes on 90 percent of earnings, not 100 percent. Unfortunately, simply removing the cap would no longer be sufficient at this stage. Even if we could snap our fingers and institute this change tomorrow, we would find ourselves at reserve depletion sooner than 2063 (see Figure 4); the gap between future tax revenue and benefits payments is too large.

Figure 4

Still, this raises an important point about the FICA tax cap: It is a potential failure point for the health of the system as a whole. If earnings inequality diverges from what is expected, then the formula legislators set for annual increases in the FICA tax cap will result in unintended fluctuations in the percent of earnings subject to payroll tax. And that means OASI could be inadvertently starved of necessary revenue, as it has been since 1983. One “simple” way to solve this problem is to remove the cap entirely. But, as optimal policy and optimal politics don’t always line up, another possible solution is discussed below.

Compensation vs. Earnings

As noted, earnings for most workers did not grow as quickly as anticipated in the decades since the 1983 reforms. But earnings are only part of the total compensation that workers receive. Over the decades since Social Security was first enacted, it became increasingly common for employers to provide perquisites as part of the employment packages offered to (mostly middle-class) workers. These perks include sick days, paid vacation, contributions to 401k and other retirement plans, and subsidized insurance premiums through employer-sponsored health insurance plans (ESIs). The latter is particularly important. Most non-retired, nondisabled individuals who have health insurance currently receive it through an ESI, and real private insurance spending per capita has grown considerably (and considerably faster than public insurance per capita spending) over the past several decades.

Employers offering compensation through perks may have also contributed to sluggish earnings growth over the past few decades. Employers have a pot of funding they are willing (see the declining worker power example above) and able to use to compensate workers, and an increasingly larger portion went into fringe benefits/perks rather than earnings during this period for a variety of reasons, including rapidly increasing health insurance costs. This matters because, while earnings are taxable under FICA, non-earnings compensation is generally not.11 It’s thus natural to ask whether policymakers should consider expanding the tax base for Social Security to include other forms of employment compensation. Perks did not become a major part of employment packages until decades after the Social Security Act. Given the changing nature of employment, shouldn’t FICA get with the times?

As noted, the SSA based its 1983 projections on an estimate of average earnings growth (already attempting to account for the negative impact of perks12) that was largely correct. It was the distribution of those earnings gains, not the slower overall earnings gains (vs. a world without fringe benefits eating into earnings growth), that was the proximate cause of the revenue shortfall. However, because Social Security’s tax base is particularly narrow (at least in terms of the types and share of compensation to which it applies) and the consequences of divergence from projections are particularly dire, the SSA has explored options for additional revenue sources. And that includes expanding FICA to include other forms of compensation not currently subject to the tax. For example, the SSA has investigated the impact of subjecting employer and employee contributions to ESI premiums to payroll taxation (scenario F3 on the Trust Fund’s actuarial status), finding a modest long-term benefit to the fund should this be enacted going forward. The details of these tax expansions matter considerably for their overall impact. For example, in the F3 scenario linked to above, contributions to ESI are also included in a modified AIME, meaning that eventual benefits paid out to Social Security recipients would also increase, somewhat dampening the effect of the increased tax revenue—there are no magic bullets here. Nevertheless, broadening the tax base to include other forms of compensation (including but not limited to ESI contributions) represents an option for increased revenue going forward and should be considered as part of any package to cover the anticipated fiscal gap.

Automatic Stabilizers and Future-Proofing

The Social Security Administration cannot and will not correctly predict every significant change in the economy over a period of 75 years. The SSA produced remarkably accurate predictions, but the small number of economic parameters that did not follow expectations have proven consequential. We can only be certain that there will be surprises—so how should we proceed?

When researchers and lawmakers convene to discuss reforms to OASI, they should, of course, consider what might go wrong. In 1983 it was earnings inequality. In 2034 it might be something else. Some creative thinking can lead to better risk assessment and a stronger plan. But there will inevitably be “misses,” and some may prove important to the health of Social Security.

This would not be a particularly large problem if we could count on legislators to quickly resolve issues when actuaries detect a deviance from initial projections, but politicians of all stripes have historically been loath to touch Social Security until and unless there is no choice. That earnings growth was more unequal than anticipated and in important ways became clear within a few years of the 1983 reforms. A quick adjustment to the FICA cap formula to account for this could have put us on more stable footing. But there was apparently little appetite from lawmakers to revisit the issue.

If lawmakers won’t regularly revisit a policy to tweak as necessary, what can be done? This paper discussed the idea of removing the FICA cap entirely. Policymakers and researchers might work to systematically identify and eliminate similar features that fail to function as intended if and when economic conditions diverge from projections. But it is not likely we can make a social security system (or any system) without any such features.

Another possibility is to build in automatic triggers for the program: tax increases or other adjustments that automatically activate when revenue is lower than projected by a certain percentage or for a particular length of time (or, conversely, when benefits increase above projection by a certain percentage or particular length of time). This was, in fact, suggested in the 1983 Trustees Report. It describes a system of periodic automatic adjustments to the taxable maximum to maintain the 90 percent target in the event that earnings growth became more unequal than anticipated. But legislators obviously did not include this system in the 1983 reforms, and here we are. If such automatic triggers were included in the next round of reforms, however, they could produce a “sustainably solvent” Trust Fund with automatic adjustments turning on/off to steer the Trust Fund as necessary.

This sounds good, right? However, you may have noticed one wrinkle: Lawmakers have little appetite to touch Social Security unless an impending shortfall requires it. So the automatic stabilizers that are put into place in this scenario are likely to remain in effect for a long time. And there is no accounting reason why those stabilizers should necessarily be focused solely or mostly on revenue generation. There could also be automatic triggers that slash benefits gradually (through changes to the cost-of-living-adjustment formula) or raise the retirement age, for example. In other words, if we are contemplating such a step, the composition of government at the time the reforms take place becomes even more important than it currently is in determining who will bear the costs of keeping the Social Security system running smoothly going forward.

We cannot let a narrative of “impending bankruptcy” scare people into believing OASI will not be there for them or into supporting drastic and unnecessary changes to the program (e.g., “privatization”).

Conclusion

We cannot let a narrative of “impending bankruptcy” scare people into believing OASI will not be there for them or into supporting drastic and unnecessary changes to the program (e.g., “privatization”). Social Security’s current difficulties are a combination of the quirks of the laws governing it (a separate and limited funding source, no capacity to borrow, etc.) combined with some important “misses” in actuarial projections and legislators’ unwillingness to legislate. If OASI was funded from general revenues there would be no problem; if actuarial projections had been correct there would be no problem; if legislators had been willing to revisit reforms based on new data there would be no problem. There is a real fiscal shortfall—but one that lawmakers can and will directly address with bridge funding in the short term and legislative reforms in the long term. There is no bankruptcy or collapse in the cards; just like in 1981, we are simply waiting for lawmakers to act.

But the upcoming Trust Fund reserve depletion will require our attention. It may seem unfortunate that we have to revisit Social Security decades sooner than anticipated. But it’s also a chance to strengthen the program: We can secure and even expand the program using what we have learned over the past few decades. That includes knowledge of the program’s failure points, ideas for new revenue sources and new approaches, and the understanding that we will inevitably get some things wrong. But there are many different ways to shore up OASI’s fiscal deficit and to apply these lessons, and policymakers must take care to choose those that do not place the burden on the most vulnerable among us.

The National Academy of Social Insurance polling has shown that, when offered the chance between maintaining the status quo and creating a more generous OASI benefit, large bipartisan majorities favor the latter. And when offered the choice between a variety of policy packages that would all close the Trust Fund’s fiscal gap, a large bipartisan majority favors packages that focus heavily on tax increases and other revenue generators rather than on benefits cuts. That suggests a path forward for Social Security that would both be generous and generate popular support. But that path depends on what the decision-makers at the table decide to prioritize as we approach 2034: short-term fixes that kick the can down the road, or genuine reforms to ensure Social Security fulfills its purpose of protecting all Americans in old age. That choice, rather than predictions of doom, is what we should be focusing on going forward.

Footnotes

- Congress borrowed the funding from the Social Security Disability Insurance Trust Fund and the Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. ↩︎

- You may hear the term OASDI used for Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance. This combines OASI and Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI). Both are funded through FICA payroll taxes, and both pay out benefits using analogous trust fund structures. However, the Social Security Administration tracks the fiscal status of the SSDI Trust Fund separately. This fund is not expected to deplete its reserves anytime soon and thus is not included in the present discussion. ↩︎

- After Medicare was created as part of the Social Security Amendments of 1965, a separate FICA payroll tax to fund it was added. ↩︎

- In reality, employer contributions to any tax or perk are partially funded through reduced salaries. This has implications for the Social Security Trust Fund reserve discussed below. Self-employed individuals, for comparison, have to pay the employer contribution themselves as part of the Self-Employed Contributions Act (SECA) tax. ↩︎

- OASI also receives revenue from income tax on Social Security benefits applied to high-income households and from the interest payments discussed in this paragraph. ↩︎

- Actually 80—the SSA initially estimated that the reforms enacted would carry the Trust Fund through 2063. ↩︎

- Note that the cost (the numerator) is not increasing; the taxable payroll (the denominator) is decreasing which causes the product, “cost as percentage of taxable payroll” to increase. ↩︎

- This line is fairly flat because the FICA tax is a percentage of taxable income and it remains stable except for increases scheduled as part of the 1983 reforms. ↩︎

- In fact, it would last slightly longer, since in this scenario (the earnings gains that actually occurred plus additional tax revenue) eventual benefits payments for most workers would be slightly lower than assumed in the 1983 projection. ↩︎

- This estimate depends on whether benefits are also credited for earnings above the current-law taxable maximum. ↩︎

- 401k contributions are the notable exception and have been subject to FICA tax since the 1983 amendments. ↩︎

- The 1983 projections assume an average annual wage growth of only 1.5 percent while projected GDP and employment growth imply a roughly 2.2 percent annual growth in real compensation, capturing the impact of perks. We thank Stephen Goss for pointing this out. ↩︎

Suggested Citation

Nuñez, Stephen. 2026. “‘Will Social Security Run Out?’ Is the Wrong Question: How Lawmakers Can Protect Beneficiaries and Strengthen OASI.” Roosevelt Institute, January 15, 2026.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Stephen Goss, Kathryn Edwards, Oskar Dye-Furstenberg, Katherine De Chant, Kathleen Romig, and Aastha Uprety for their feedback, insights, and contributions to this paper. Any errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies are the author’s alone.