The Institutional Foundations of Free Speech at Public Universities

January 27, 2026

By Luke Herrine

This is a web-friendly preview of the report.

Key Takeaways

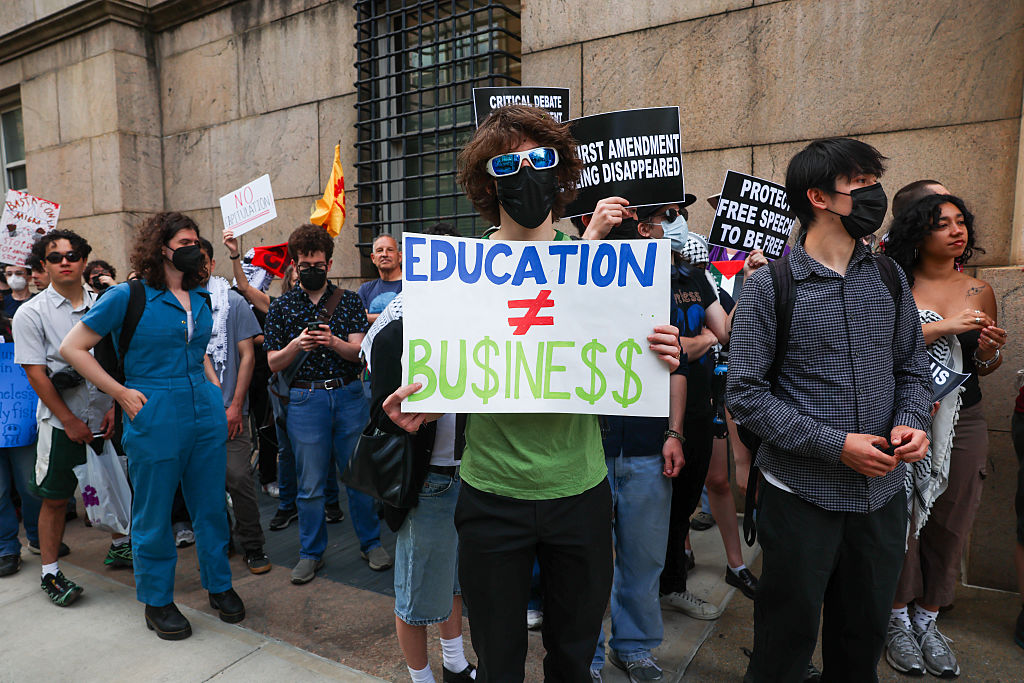

- As political repression worsens, building resilient universities will require institutional creativity. In an era of eroding norms, exploitative settlements, tightly coordinated attacks on left-wing ideology, and the suppression and even detainment of student protestors, defending free speech demands thoughtful redesign rather than simple policy fixes.

- Public universities are not uniquely vulnerable to speech repression. Governments, internal university actors, and private external pressures all pose threats to free expression across both public and private institutions.

- Courts provide an important but limited backstop for free speech. While First Amendment protections matter, day-to-day governance decisions shaping speech are driven primarily by trustees, administrators, faculty, and accreditors.

- Lay boards should have less power and scholars should have more. Historically, trustees have been the least protective of free speech, administrators occupy an unstable middle position, and faculty consistently play the strongest protective role.

- Robust public funding supports academic freedom. Well-funded public universities are better positioned to protect free inquiry and should be seen as allies, not adversaries, of free speech.

Introduction

Systems of higher education in free societies must be committed to freedom of speech in two senses. First, in order to serve their social function of the creation and dissemination of knowledge and critical inquiry, a well-functioning system of higher education must commit to the basic elements of academic freedom—allowing professors “full freedom in research and in the publication of the results,” “freedom in the classroom in discussing their subject,” and freedom from “institutional censorship or discipline” when publicly expressing political views informed by their professional knowledge.1 Second, in order to nurture critical perspectives in public debate and to enable the free development of political consciousness, universities should serve, as much as possible, as open forums for free expression, allowing a wide range of political expression from both faculty and students, both on and off campus.2

One perennial worry about shifting to a system of universal free public higher education—heard frequently in informal discussions but rarely articulated at length—is that doing so would make it too easy for the government (state or federal) to interfere with universities, undermining the two freedoms that make them so important. This worry is amplified in our current environment of government repression. It is incumbent upon those of us who promote free public higher education to grapple with how to ensure public universities are designed to promote “free speech” in a broad sense.

This report draws on US history to broach that inquiry in two steps.

First, this report cautions against the simple view that public universities are uniquely likely to repress speech. This view is tempting because speech repression is most naturally imagined as an authoritarian government subordinating all institutions to the priorities of the authoritarian rulers. The reality of repression is more complex. Threats from the government can be, and regularly are, targeted at both public and private colleges (as, indeed, is true of current threats from the Trump administration, which has been putting pressure on elite private universities at least as much as public universities). And plenty of efforts to limit speech, legitimate or illegitimate, come from inside the university (for example, students demanding to be protected from ideas that challenge their beliefs, or administrators cutting programs without sufficient business application) and from nongovernmental outsiders (such as corporations seeking to repress evidence of the harms of their products). Developing an environment conducive to free speech at public universities thus involves more intricate governance questions, most of which are not unique to public universities.

Second, this report clears ground for these subtler governance questions by mapping out how different university constituencies have tended to respond to (and/or generate) free speech challenges throughout history. Ever since federal courts began to extend First Amendment protections to faculty and students of public universities in the middle of the 20th century, they have played a crucial backstopping role both in providing recourse for infringements and in setting norms. But this role has been limited in several respects. Other players—trustees, senior administrators, and faculty, as well as accreditors and other third-party reviewers who play a reinforcing role—have been more influential when it comes to day-to-day governance questions surrounding free speech on campuses. In general, trustees have been least reliable in promoting academic freedom and robust on-campus debate, while faculty have been most reliable. Senior administrators have been caught in between—seemingly more strongly protective of speech norms when faculty have more power, and less when trustees have more. The role of students, legislators, and governors, while important, is left for future work.

This report then puts forward a few hypotheses about how future higher education governance regimes might support—or fail to support—more robust free speech. First, legislatures and universities can and should develop (or create independent governance bodies that can develop) more detailed standards for evaluating different free speech challenges than are currently articulated in court doctrine. Second, developing a set of rules—and even a process for the administrative enforcement of those rules—will not suffice; as we are currently witnessing, the rules do not hold fast if people are not willing to fight for them. Therefore, those serious about institutional design must ask which constituencies are likely to fight for free speech, and then empower them. Because trustees are the least likely and faculty the most likely to fight for free speech, governance should shift power from the former group to the latter. Third, robust public funding for higher education makes free speech—and especially academic freedom—easier to promote. In other words, well-funded public universities should be seen as protectors of rather than enemies to free speech.

There is no simple solution to building universities to withstand censorship or, beyond that minimum, to create environments that inculcate clear thinking and knowledge of the world and promote free exploration thereof. In our age of collapsing norms and assaults on familiar institutions, creative rebuilding will be required.

Footnotes

- “1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure, with 1970 Interpretive Comments,” American Association of University Professors (AAUP), https://www.aaup.org/sites/default/files/1940%20Statement.pdf. ↩︎

- Not all observers agree with this dual purpose of universities and much depends on the specification of each, but it is beyond the scope of this report to get into those theoretical weeds. For general discussion of the relationship between the values of free speech generally and the distinctiveness of the university, see Robert Post, Democracy, Expertise, and Academic Freedom: A First Amendment Jurisprudence for the Modern State (Yale University Press, 2012); Paul Horwitz, ed., First Amendment Institutions (Harvard University Press, 2013); Keith E. Whittington, Speak Freely: Why Universities Must Defend Free Speech (Princeton University Press, 2019). ↩︎

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Noa Rosinplotz, Shahrzad Shams, Suzanne Kahn, Robert Post, Aastha Uprety, and Rachelle Klapheke for their feedback, insights, and contributions to this paper. He would also like to thank Ellen Schrecker, Isaac Kamola, Tariq Habash, and Eleni Schirmer for sharing their experience and knowledge during the research for this paper. Any errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies are the author’s alone.

Suggested Citation

Herrine, Luke. 2026. The Institutional Foundations of Free Speech at Public Universities. New York: Roosevelt Institute.