The Official #ConspiracyTheoryJobsday Is Coming!

January 30, 2026

By Michael Madowitz

There are arguably two jobs days coming up next week: On Friday, February 6, we’ll get both the actual January report—our clearest real-time snapshot of the economy—and the annual benchmark revisions, which are likely to dominate coverage. This means there are at least two parallel labor market stories to watch (and possibly a third depending on how erratically the president reacts to the revisions): the backward-looking revisions, which are likely to cement 2025 as one of the worst years for job growth outside a recession, and the forward-looking jobs numbers, which will indicate whether things are getting any better or worse.

What to Expect When You’re Expecting Benchmark Revisions

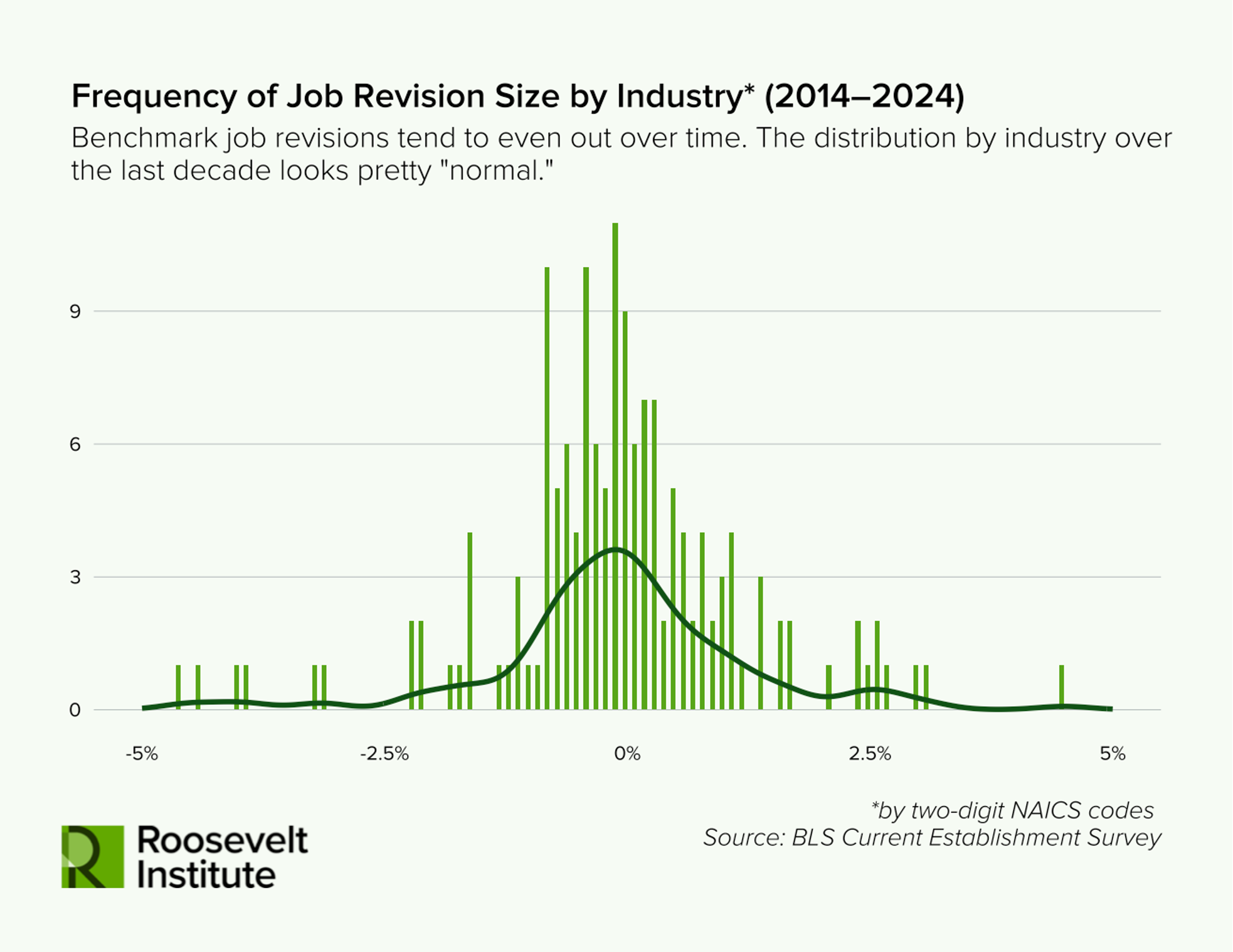

Benchmark revisions are an annual feature of many key economic data releases. Because there’s often a trade-off between speed and accuracy, the initial numbers come out quickly, and the revisions process is how we ultimately get higher-quality data without waiting months for the first estimate.

As headlines go, this will make waves. 2025 was already a bad year for jobs, with job growth falling from over 2 million in 2024 to 584,000, but, if we revise from adding around 600,000 jobs to losing 250,000 or more (as the September data forecasts suggest), the headlines are unlikely to be subtle. Economists and job market watchers won’t be thrown by revisions (up or down) of around 0.6 percent in an economy with more than 160 million jobs, and these numbers tell us less about how the economy is doing now than they do about the year behind us. Going forward, the real-time data is important because the job market is not great.

Revisions to data are a sign of accuracy, not inaccuracy or conspiracy. It’s difficult to cook the books when you publish very detailed recipes. To see why, it helps to understand the two surveys that make up the jobs report and how each is revised.

The jobs report comes from both a survey of households and a survey of businesses. The household survey is not revised throughout the year because real-time answers from the people surveyed in households are more accurate than their memories. The population estimates used in household figures are revised annually, but the new data are only used on a forward-looking basis. This is one reason jobs nerds prefer to talk about percentages of the population: The number of employed people is often not comparable in certain months because projected population changes themselves can create significant shifts.

Business surveys (which give figures like the 50,000 jobs added in November) are revised, both throughout the year and annually. Each jobs report includes revisions to the previous two months of data as late responses from businesses about their payroll records come in (with less recall bias than household responses because payroll records are recorded for tax purposes).

The annual benchmark revisions to the business survey are primarily about adjusting estimates to changes in population and to the constantly changing number of businesses. Unlike household data, these estimates are used to revise job gains looking backward. The underlying reports from businesses do not change, but the weights used to translate survey responses into estimates by industry and across the economy for the last 21 months are updated, which can affect data going back up to five years. This is normal, and we know what to expect because preliminary data released this fall estimated that businesses are likely to have added close to 900,000 fewer jobs this year than previously estimated.

The Actual Jobs Situation

The job market is weak (especially in the business data) and murky (in the household data).

Essentially, the picture from the household side is a hazy job market that seems to be holding up reasonably well, in part because workforce growth has been anemic at best. With missing household data for October and a compressed survey period for November due to the last government shutdown, the trends in the labor market are harder to identify in the household survey, but the economy seems pretty stuck in neutral. Employment rates and participation rates for 25- to 54-year-old workers are marginally better now than they were a year ago, though, across all ages, most labor market measures are flat to marginally weaker over the last year, with more acute signs of stress among Black workers, in long-term unemployment, and in involuntary part-time work, among others.

On the business side, the job market continues to show weak overall job growth, concentrated in a small number of large sectors. Health care and social assistance combined with leisure and hospitality constitute roughly 25 percent of employment, and these two sectors have added more jobs than the other 75 percent and than the economy overall because job growth in the rest of the economy has been so weak.

More worryingly for recession watchers, job growth among especially cyclical industries—the ones that gain jobs in expansions and shed jobs in recessions—has been negative. In trade-exposed industries like manufacturing, mining, and logging, these job losses could point to less acute but more permanent declines if foreign markets become less open to US goods in response to tariffs or other aggressive policies. But the concern extends to cyclical parts of the service sector that are not trade-exposed, like temp jobs and employment services.

A stronger 2026 job market is going to require broader job growth, and these cyclical industries are the place to watch for the economy to turn around first. But that turnaround, if there is one, will happen in 2026 job growth, not in 2025 revisions.