50 Years In, Most SSI Recipients Live in Poverty. That’s a Policy Choice.

October 10, 2024

By Stephen Nuñez

This year marks the golden anniversary not just of Nixon’s resignation or the Happy Days premiere, but of a safety net program that’s been showing its age for a while now: The Social Security Administration’s Supplemental Security Income (SSI) program.1 Fifty years ago, SSI launched with the goal of offering aid to adults and children with disabilities, and to older adults with little to no income or assets. And it has since served as a crucial source of aid for millions of Americans, serving 7.4 million beneficiaries each year.

Much has changed in the last five decades. Other income support programs like the Child Tax Credit and the Earned Income Tax Credit have lived multiple lives, evolving and (sometimes) expanding with the political times. But over the last 50 years, SSI has operated largely unchanged. That’s had dire consequences: Despite its legislative intent to assure that older and disabled people would never have to “subsist on below-poverty incomes,” more than 50 percent of SSI recipients in 2016 lived in households that fell under the poverty line even after including the SSI benefit. Compare this with the poverty rate of Americans aged 65 and older, which generally hovers at or below the 18–64 poverty rate (10.3 vs. 10.5 percent in 2021) due in large part to the success of the broader Social Security program.

That ongoing failure has been a longtime focus of disability advocates and lawmakers, who have used the program’s milestone birthday to draw new attention and call for updates. Due to their efforts, we have some administrative efforts to improve access to SSI. For example, the Social Security Administration issued two regulations that went into effect last month and altered the program’s means test, improving access by making eligibility calculations less punitive.

These changes in statutory implementation can make a difference on the margin, ensuring SSI recipients can access more of the SSI benefit. But regulatory tweaks can only go so far. There are larger problems we still need to address, and these will require legislation.

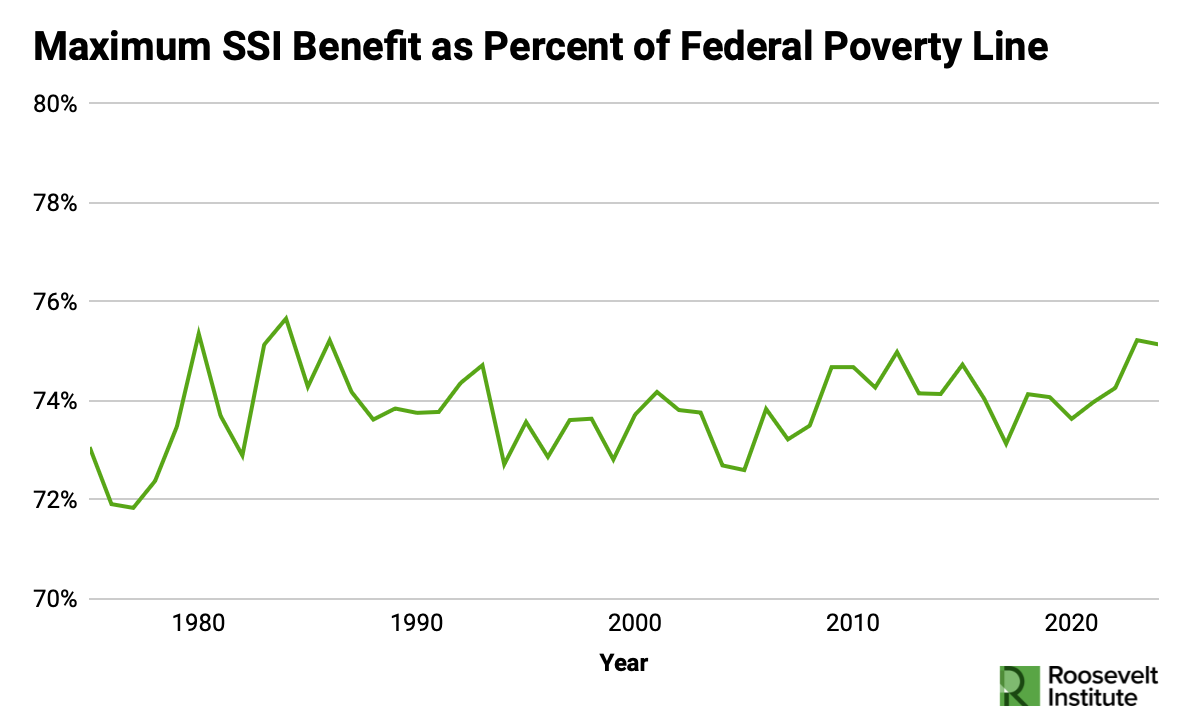

Though people can access more of it, the benefit is still paltry. The maximum benefit has hovered between 71 and 75 percent of the federal poverty line for its entire history. To make matters worse, benefits are subject to a particularly extreme form of means testing. SSI offers few exemptions in its benefits formula—most income, whether earned or unearned, counts against the SSI benefit. This includes “in-kind support and maintenance,” which counts the “market value” of living with a relative or a friend making meals, reducing monthly benefits. The program does exclude a portion of income from the means test—a whopping $20 for unearned and $65 for earned income each month—but these have not been updated since the program launch (the real value of those income disregards have declined by roughly 84 percent since then). And while most means-tested benefits phase out gradually as income increases, SSI benefits are reduced by $1 for every $2 in earned income. This is effectively a 50 percent tax on income (much higher than the highest marginal income tax rate of 37 percent paid by the highest-income Americans), making it difficult, if not impossible, for SSI recipients to get ahead.

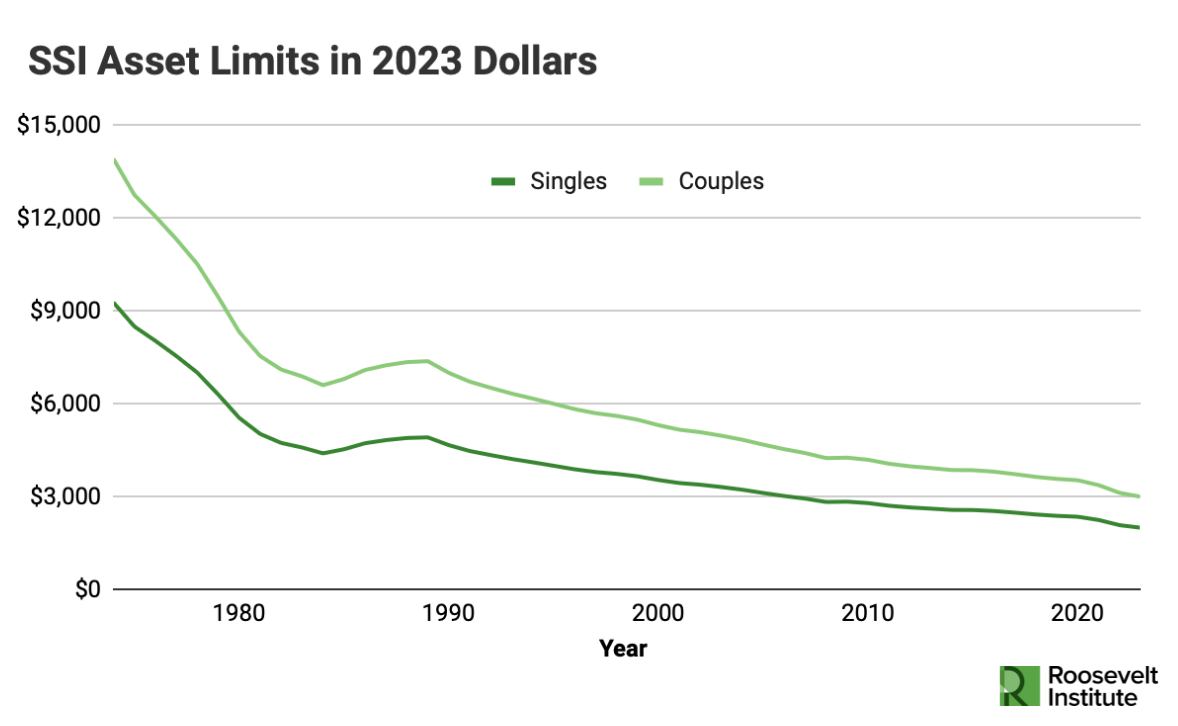

Like many US safety net programs, SSI also pairs its means test with an asset test, meaning that those who possess assets (e.g., cash savings, stocks, retirement accounts) valued in excess of the program’s specified threshold are ineligible for benefits. As with its means test, the SSI asset test is particularly strict: $2,000 for individuals and $3,000 for couples, with no adjustment for inflation. Roughly 70,000 recipients have their benefits suspended and 40,000 recipients have their benefits terminated each year due to exceeding the asset cap. Although the goal of asset tests is ostensibly to direct aid to those who need it most, in practice they generate increased paperwork burden on recipients and administrators, discourage saving for emergencies and retirement, produce benefit “churn,” and leave recipients without a pathway for economic mobility. As such, several states have, over the years, loosened or removed asset limits from the benefits they administer, such as SNAP. But SSI beneficiaries have been left waiting for such relief since 1989, when the current limits went into effect (the real value of the asset limit has declined by roughly 59 percent since then).

If we want to tackle these problems, we’ll have to do it in the halls of Congress. While some legislative proposals have been put forward over the last few years, none of these efforts have gotten much traction. For example, the SSI Savings Penalty Elimination Act, a bipartisan bill led by Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown and Republican Senator Bill Cassidy, would raise the asset limits to $10,000 for individuals and $20,000 for couples and, importantly, index the limits to inflation to prevent a reduction in real value over time. In addition to offering SSI recipients a simple way to save money without fear of losing their benefits, the bill has proven to be popular with the business community, earning the endorsement of the US Chamber of Commerce and the CEOs of several major companies, such as JPMorgan Chase and Microsoft. What’s more, the Social Security Administration’s actuaries estimate that this reform would cost the federal government on average less than 1 billion dollars a year over a 10-year period. In short, the SSI Savings Penalty Elimination Act is a cheap and broadly popular reform that could improve the lives of SSI recipients—the closest thing to a no-brainer in federal policy. And yet, it’s gone nowhere.

Passing the SSI Savings Penalty Elimination Act immediately would be a simple enough first step. But the bill’s higher asset limits can only do so much when SSI recipients don’t have sufficient income to save. The Supplemental Security Income Restoration Act of 2024 proposes a broader suite of reforms, setting the maximum benefit at the federal poverty line and a variety of updates to the means testing formula, including, crucially, automatic inflation adjustments to maximum benefit and income disregard levels. The Social Security Administration estimated that an earlier version of this bill would cost roughly 50 billion dollars a year over a 10-year period, with the changes to the maximum benefit alone only costing about 35 billion dollars a year. Bringing SSI recipients to just above the poverty line is, of course, still a low bar, but the legislation would provide a better foundation to build on.

Combating poverty is not rocket science. The American Rescue Plan’s Child Tax Credit expansion showed us that we can effectively combat poverty simply with more generous and less restrictive cash assistance (and what happens when vital aid expires due to political failure). The expiration next year of many of the Tax Cut and Jobs Act’s provisions will set the stage for a battle over benefits. Democrats are planning to use this opportunity to push for a restoration of the ARP CTC expansion because cutting child poverty has become one of their top priorities (as well it should be). We have the means to cut not only child poverty in half, as the ARP CTC expansion did, but poverty among the disabled and elderly individuals who rely on SSI as well. It’s not a question of know-how or money; it’s a question of priorities. As policymakers set their goals for next year’s horse trading sessions, they should, for a change, prioritize SSI’s forgotten recipients. The poverty of millions of SSI beneficiaries is a policy choice, as it’s been for the last 50 years.

Footnote

Read the footnote

1Unlike Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI), the program people often refer to colloquially as “social security,” SSI is not primarily a retirement benefit.