How the Global Minimum Tax Deal Could Bolster Democracy and Make Government Work Better

October 14, 2021

By Todd N. Tucker

Last week’s historic announcement of a global minimum tax agreement among 136 nations was rightly celebrated as a victory not only for the economy but for democracy. After 100 years of tax rules that gave multinational capital ample places to hide and evade social responsibilities, the biggest multinational corporations will now be taxed at least partly based on where they actually do business—a sea change that could lead over time to a more just (and democratic) international distribution of resources.

The agreement has the potential to help restore trust in government by demonstrating its ability to be evenhanded. Indeed, as Roosevelt Chief Economist Joseph Stiglitz, Gabriel Zucman, and I wrote in Foreign Affairs last month, this new deal could form the basis of decades of shared global progress on the climate, economic inclusion, and even world peace—making possible a new social contract that replaces one corroded by decades of rising inequality.

But the announcement was also historic and democracy-reinforcing in another, less obvious way.

The How Is as Important as the What

Since the Hoover administration, successive administrations have chosen to pass international tax agreements as treaties requiring two-thirds support from the Senate only, rather than as legislation requiring simple majorities in both the House and the Senate.

Earlier this month, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen indicated openness to changing this past practice, testifying before the Senate Banking Committee that a treaty vote was only “one way” to enact the changes. According to a letter from three Republican senators objecting to this possibility, a nominee for a senior Treasury position has also said that an “updating” of international tax rules “could occur through several means, such as through an Article II treaty, congressional executive agreement or through legislation overriding the existing treaties.” The latter two mechanisms would only require a majority of senators to vote for passage.

There are good arguments for requiring tax changes to involve the House. As Professor Rebecca Kysar of Fordham University School of Law argued in a 2013 article for the Yale Journal of International Law, the US Constitution’s “Origination Clause” in Article I, Section 7, Clause 1 states that “All Bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives; but the Senate may propose or concur with Amendments as on other Bills.” The founding generation, having just fought the Revolutionary War over tax disputes with King George, wanted to ensure popular control over taxation prerogatives. Kysar, now an official at the Treasury Department, further argues that the Constitution’s Origination Clause trumps its treaty language, calling into question the legality of the past 90 years of tax treaty practice.

The Deal Could Upend the Senate Minority’s Expansive Veto Powers

This isn’t only a question of constitutional propriety. It’s a fight over whether a tiny one-third minority of the US Senate will have a veto over the Biden administration’s ability to enact “foreign policy for the middle class.”

Foreign policy—including international tax policy—has long been dominated by elite interests, as indicated by the willingness of past administrations to engage in war, unbalanced trade agreements, and elite-favoring tax policy. Centering the needs of the working class—as the administration says it wishes to do—has rightly been heralded as a major change, and is a prerequisite for ensuring a legitimate and effective response to the crises humanity is facing.

Executing that pivot requires confronting not only the so-called “democratic deficit” of international agreements but the democratic deficits at home.

Chief among those are arcane practices like the Senate filibuster and two-thirds Senate treaty vote requirements.

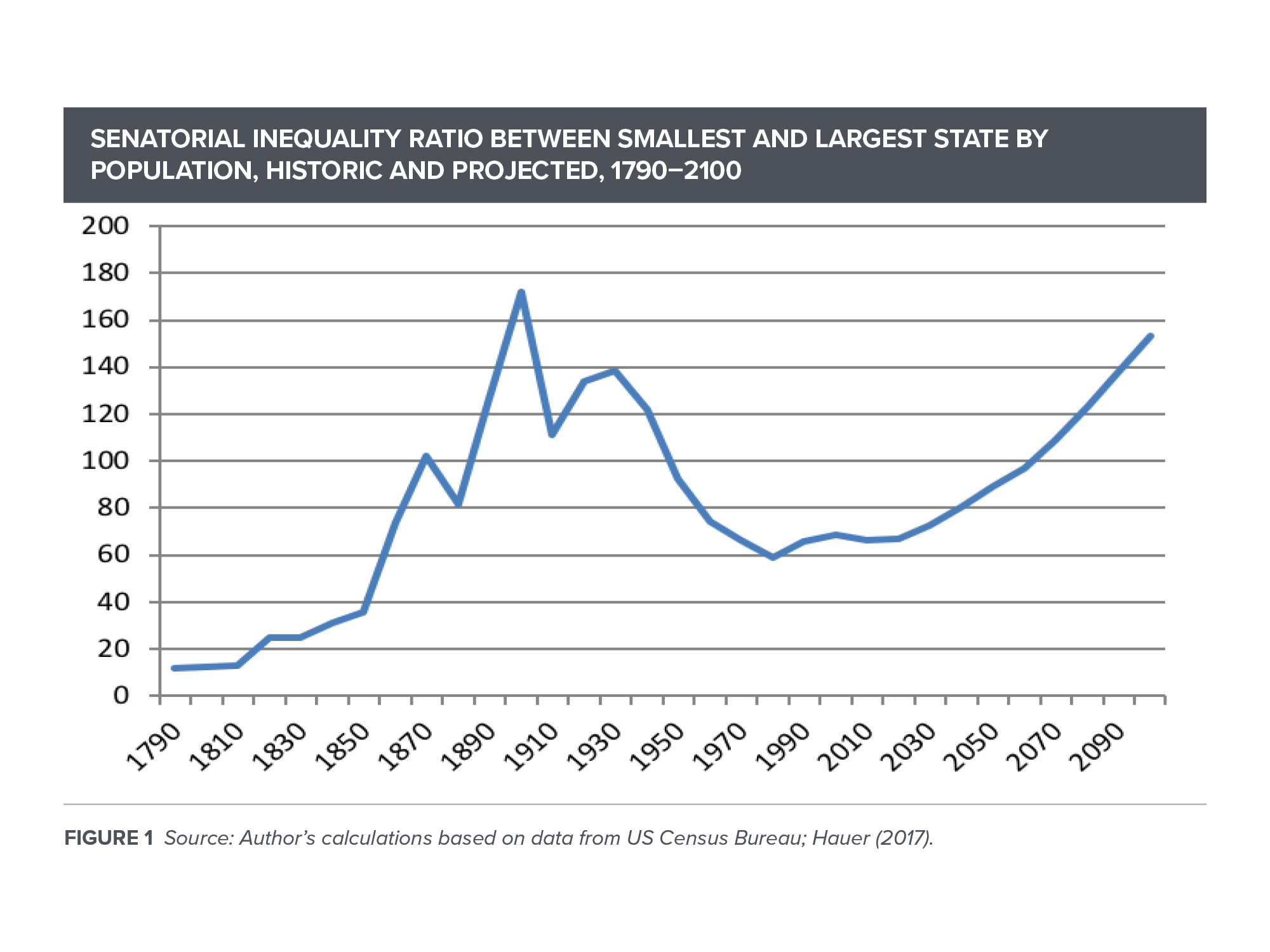

The US Senate is the developed world’s least representative legislative chamber. It is deeply countermajoritarian, and is only slated to get worse, as population shifts due in part to climate change will cluster voters in certain states. This is depicted in Figure 1 below, which lays out the relative power of the least represented state in the Senate (currently California) to the most overrepresented state (currently Wyoming). While this disparity is 67-to-1 today, it will more than double to an estimated 167-to-1 by the end of the century.

America’s “upper chamber” is in desperate need of comprehensive reforms, such as those discussed in our 2019 Roosevelt report Fixing the Senate. But to ensure that future international agreements to help workers and the environment are not hamstrung by 34 senators representing tiny and disproportionately white shares of the population, the bare minimum policymakers can do is pass more agreements by simple majority vote in the House and Senate.

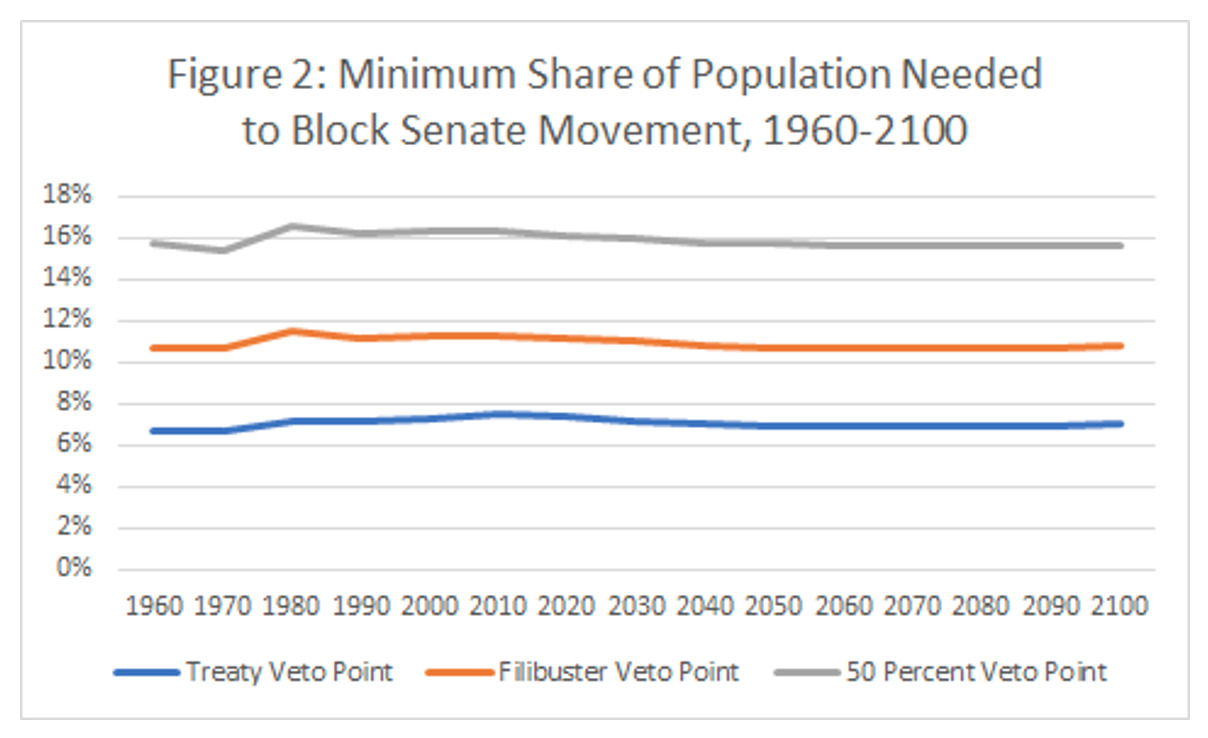

As Figure 2 shows, even at present, senators representing no more than 6 percent of the population could block Senate treaty action. (Though it is worth noting that senators representing around 10 percent of the population could block the overcoming of a filibuster, and no more than 16 of the population could produce a 50-senator majority—if all senators from the 25 smallest states voted the same way.)

This is no mere arithmetic quandary. As tax attorney Mindy Herzfeld has noted,

The challenges this agreement would face in Congress are much broader than just one Senator being a holdout. I think you’d have a very hard time getting any Republican votes, or more than a handful possibly. For the foreseeable future, there will be a large number of Republicans who are more likely to oppose any kind of global tax agreement like this.

With Congress already deadlocked on many other questions, it is difficult to imagine Biden’s tax proposals attracting the support of 17 Republicans—the minimum threshold necessary to pass a two-thirds (67 senator) treaty vote, especially with millions in corporate dollars being spent to lobby against it.

A move from Senate treaty votes to House and Senate legislative votes is not unprecedented: It’s been the norm for decades in the area of trade deals like the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Like trade deals, tax agreements implicate a wide range of public interests and would benefit from deliberation and airing in both legislative chambers. It shouldn’t be easier to pass deals encouraging multinational companies to offshore working-class jobs than it is to pass deals making sure those companies pay their fair share of taxes.

The Biden administration deserves credit for working to ensure that its policy agenda not only reinforces democracy through desirable outcomes but democratizes the process as well.