Now That That’s All Out of the Way, a 2026 Economic Preview

January 22, 2026

By Michael Madowitz

More than two weeks into the year is arguably late to preview major economic issues for 2026, but given all that’s happened since the ball dropped, it’s arguably a better time than December.

The fundamental question for 2026 is not whether US economic policymaking will become more or less chaotic, but whether the chaos will tend more or less toward self-harm. A year ago, I likened new economic policies to taking up a smoking habit, and that’s largely how 2025 played out. While daily stories focused on big market swings and the TACO-trade, the long-term story turned out to have been that the economy weakened substantially. Even amid an AI boom in the stock market, investors betting on other economies outperformed those betting on the US.

Given that we’re starting 2026 with a weaker jobs market, a weaker dollar, and stubbornly high interest rates and inflation, it’s worth digging into where things have gotten worse, which trends are showing signs of reversal, and what the big known unknowns are for 2026. Perhaps most importantly, another vibe shift is underway—the vibes are still bad, but they’re starting to come from a weak job market more than high inflation. In other words, Americans remain very concerned about affordability, but it’s increasingly a function of a weak job market and weak income growth, rather than the price growth story that has dominated headlines since the pandemic.

The State of the Economy

During the pandemic recovery, the US saw a hot job market and above-target but cooling inflation. That changed in 2025. Both the job market and inflation got measurably worse—with unemployment climbing from 4.0 to 4.4 percent and inflation jumping from 2.2 to 2.8 percent.

On jobs, the low-hire, low-fire job market is putting heavy strain on young workers and people who lose jobs. The unemployment rate for 16–24-year-olds has been above 10 percent and rising for six months, and the share of unemployed workers out of a job for six months or more is tied with the pre-2009 record. Once revisions are in, 2025 is likely to be the worst year for job growth outside a recession in decades.

Last year’s hiring numbers are projected to get worse. This February’s annual benchmark revision was projected back in September’s preliminary forecast to mean 911,000 fewer jobs in 2025, potentially turning job growth negative for the year. The question for 2026 will be whether the economy has absorbed the shocks of tariffs and immigration crackdowns and is beginning to add jobs more broadly, or if job growth will remain slow and narrowly concentrated in health and education services.

On inflation, the picture is not great, but more ambiguous. Inflation had slowed through the first three quarters of 2024, but it accelerated in 2025, partially in response to tariffs. The cost of tariffs is still not fully reflected in prices, so it’s possible companies will raise prices further to return to pre-tariff profit margins, though the effect of tariffs on prices is expected to stabilize and fade from inflation data around the middle of this year. The December 2025 consumer price index report looks good on the surface, but, upon further reflection, it appears the lingering effects of the government shutdown may have pushed these numbers down.

The question for 2026 will be whether the economy has absorbed the shocks of tariffs and immigration crackdowns and is beginning to add jobs more broadly, or if job growth will remain slow and narrowly concentrated in health and education services.

Tariffs are not the only source of policy-driven inflation. Housing affordability remains a big issue, and immigration policy and the federal budget are making it worse. The significant effect of deportations on the construction industry, coupled with new tariffs on lumber, has pushed up the hard costs of building. Financing costs for mortgages and construction have been pushed up first because budget deficits are pushing up government borrowing under last year’s tax law, which is siphoning funds from private borrowers, and because all US loans are paying higher risk premiums (even before last week’s Fed standoff), which is pushing financing costs up across the economy.

Finally, there is the evolving question of how energy prices drive inflation, which is less about volatile prices at the pump than in the past and more about steadily climbing electricity prices combined with a winter of high heating costs.

The State of the Vibes

The vibes are bad, but different bad. Households have soured further on the economy over the past year, even as their inflation expectations have stabilized and expected gains in real incomes have risen. What appears to have changed as we enter 2026 is that households have much greater anxiety about the job market. While vibes are still worse than they have historically been relative to economic conditions, they are changing in interesting ways—with the overall trend turning pretty consistently negative over 2025.

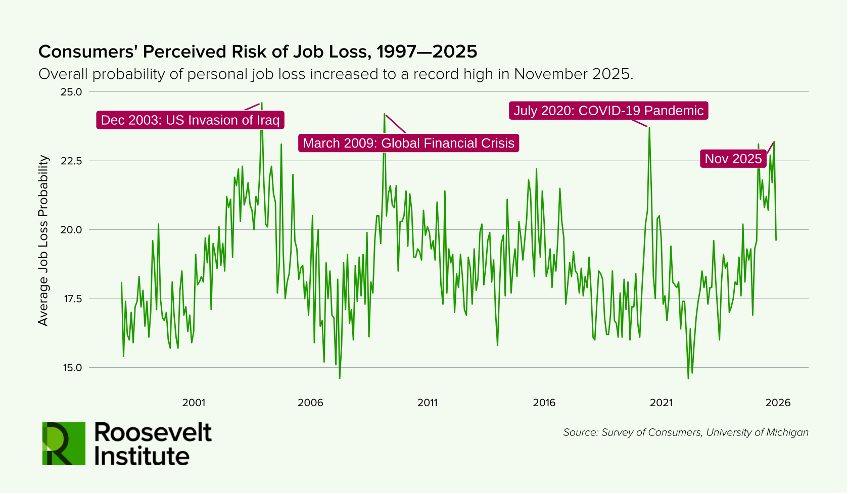

Affordability remains a major concern, but households are lowering their inflation expectations and are now worried about losing jobs at historic levels. The Michigan Consumer Sentiment survey has asked households every month since 1997 what they think the odds are of losing a job in the next five years. There have been only three months in more than two decades of measuring in which people felt more afraid of job loss than they did in November 2025. The New York Fed reports consumers have become much more worried about missing debt payments over the past few months. Turns out vibes are bad about a lot of things, not just inflation.

Strange Things Are Afoot with Last Summer’s Tax Cut

The Trump administration enacted a large tax cut for the wealthy last year, but the implementation was strange. Normally, the IRS updates tax withholding in response to new tax legislation, but this time it did not. That has led the administration to claim unusually large tax refunds are coming, but it’s not clear exactly what that means and for whom.

This could have big downstream implications for the US economy—and they don’t all point in the same direction. Large refunds could increase deficits more rapidly than currently expected and have significant implications for the inflation outlook. The distribution of refunds is likely to be uneven—they won’t be helping out lower-income households much. But significant tax cuts are coming at the top, particularly for top earners in blue states. Whether this creates K-shaped inflation or amplifies the gap between the haves and the have-mores is an open question.

The Supreme Court Does Economic Policy Now

The Supreme Court may toss the existing tariffs, or it may not ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. There is a potential win for affordability to be had here, but the administration appears eager to revert to a new tariff if it loses. The Supreme Court also has a lot to decide on Federal Reserve personnel—at this point, it’s anybody’s guess exactly how sideways this goes.

The Continuing Fall of Oil Prices and Rise of US Energy Prices

It’s wild that so much unrest in oil-producing countries has had so little effect on oil prices, but that’s the state of things until OPEC decides otherwise. What’s new is that US natural gas is creeping up in price as oil prices skim historic lows. Natural gas is still the largest source of US electricity at ~43 percent, but even though US natural gas production has grown rapidly, prices aren’t falling.

Large increases in electricity demand from the AI build-out and further utility price increases stemming from growing natural gas exports are raising the cost of generating electricity, while the cost of climate change is increasingly raising the cost of getting power to homes. These are not the gas price jumps that freak drivers out and fade in a few months but longer-term price increases that may have larger impacts over time because household energy costs rarely fall. With growing demand from AI and increasing export capacity, the US is likely to set another record for natural gas production this year, but prices are rising rapidly for the winter heating season, which is forecasted to be more expensive than last year, especially for natural gas heating.

Conclusion

After a year of moderate stagflation, 2026 is expected to be a pretty meh economic year—the predictions of booms or recessions are pretty few and far between. But the US economy has given up a lot of strength over the past year, and Americans are very concerned about the economy in general and the job market in particular. There’s not a lot of slack in the system, and, if the first few weeks of the year are any indication, the administration is eager to stress test the country and the economy.