The Hollow Energy Agenda of Trump’s First Four Months

May 29, 2025

By Oskar Dye-Furstenberg

The second Trump administration’s first four months have brought erratic economic policy and uncertainty to the energy landscape, without delivering the oil and gas boom or lower consumer costs the president promised. While the lasting impacts on the energy landscape are yet to be determined, here’s what we know so far:

- The combination of Trump’s unpredictable tariffs and his aim to increase drilling while lowering prices has caused uncertainty and uneasiness to spread among oil producers.

- Crude oil spot prices are dropping below what’s reportedly needed to profitably drill new wells. With increased OPEC+ production and cost constraints on US shale producers, American “energy dominance” remains curtailed by the realities of global interdependence.

- Although fossil fuels remain the country’s dominant source of energy, solar leads the way in new generation capacity, while wind shows signs of slowing. It’s too early to tell how much Trump’s policies are affecting clean energy investment, but the real hit will come after budget reconciliation, where the fate of Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) tax credits will be decided.

An Unclear Path to “Energy Dominance”

It’s no secret that Trump entered office signaling he was a friend to fossil fuel companies. On the campaign trail he’d made them an offer: provide $1 billion to his campaign, and in return, get a wishlist of favorable regulatory fixes. In his first week, he signed EO 14154, “Unleashing American Energy,” to remove regulatory barriers to fossil fuel expansion and revoke orders focused on clean energy and environmental justice implemented under the Biden administration. Through this executive order and others, Trump has taken steps to open the Alaskan wilderness to oil drilling, create a new National Energy Dominance Council to expedite approval for fossil fuel projects with limited oversight, roll back regulations on tailpipe emissions, renew the authorization of natural gas export permits, freeze funding allocated by the IRA, and direct the attorney general to stop the enforcement of state climate laws deemed potentially unconstitutional or preempted by federal law.

While Trump’s outward support for the fossil fuel industry—and hostility to anything addressing climate change—has been clear, the pathway to economic prosperity and “energy dominance” is less than obvious. First, there are limited federal policy tools to directly lower oil prices, with sales from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve providing perhaps the closest approximation. Instead, as evidenced by recent executive orders, the president must rely on various incentives to influence what ultimately remain private market actors’ investment and production decisions. Furthermore, despite the striking growth of US crude oil production, the leading members of the OPEC+ cartel maintain a dominant influence over international prices.

Second, there are good reasons to be skeptical that “unleashing” American energy production to lower prices is actually compatible with the interests of the fossil fuel executives the president pledged to support.

“Fifty dollars a barrel is going to hurt the United States more than benefit it, and it’s definitely not going to allow the US to produce more oil, which is something that Trump also wants to see,” Claudio Galimberti, chief economist at Rystad Energy, told the Financial Times. “The two objectives are incompatible.”

Recent history sheds light on Galimberti’s conclusion. At its highest point, one-third of recent inflation was driven by prices for energy derived from fossil-fuels. At the same time, oil and gas CEOs amassed record profits, with some of those profits allegedly stemming from explicit collusion. As ordinary Americans struggled to pay their home energy bills or afford the gasoline they needed to get to work, those same high costs were lofting corporate profits.

Price Fluctuations and Global Integration

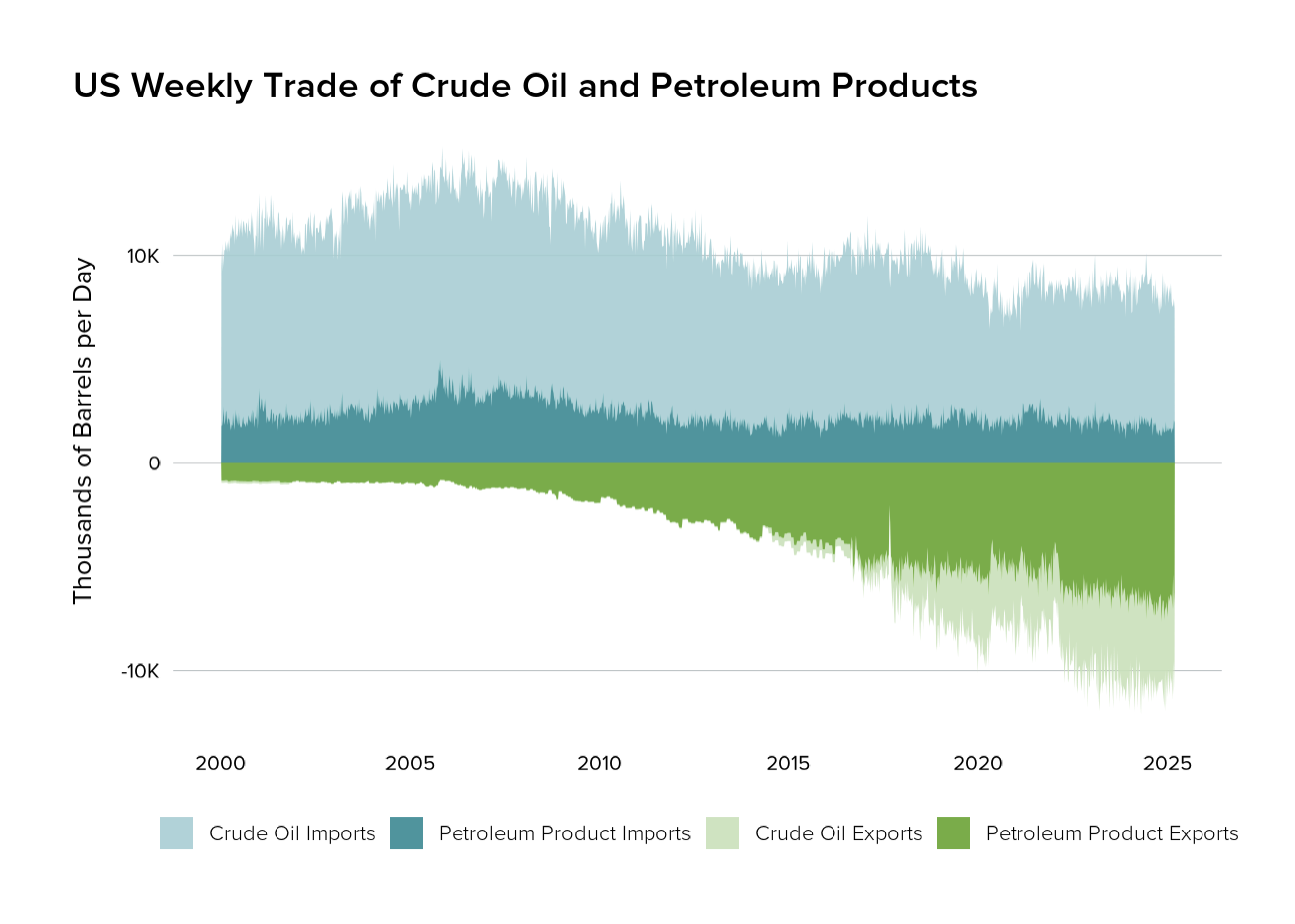

Fossil fuel companies’ high profits benefited from a spike in prices exacerbated by a drop in crude oil production and refining following tightened financial conditions during COVID-19. To this day, refinery capacity and inputs remain below pre-pandemic levels. On the other hand, production of crude oil recovered to record highs by late 2023, with the US holding its place as the world’s leader in oil production for the sixth year in a row. How does one explain the mismatched recovery between crude production and refining? In part, the answer lies abroad, with exports recovering even faster than production. Western Europe, in particular, turned to US imports following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Figure 1.

Source: EIA, Petroleum & Other Liquids, Weekly Imports & Exports

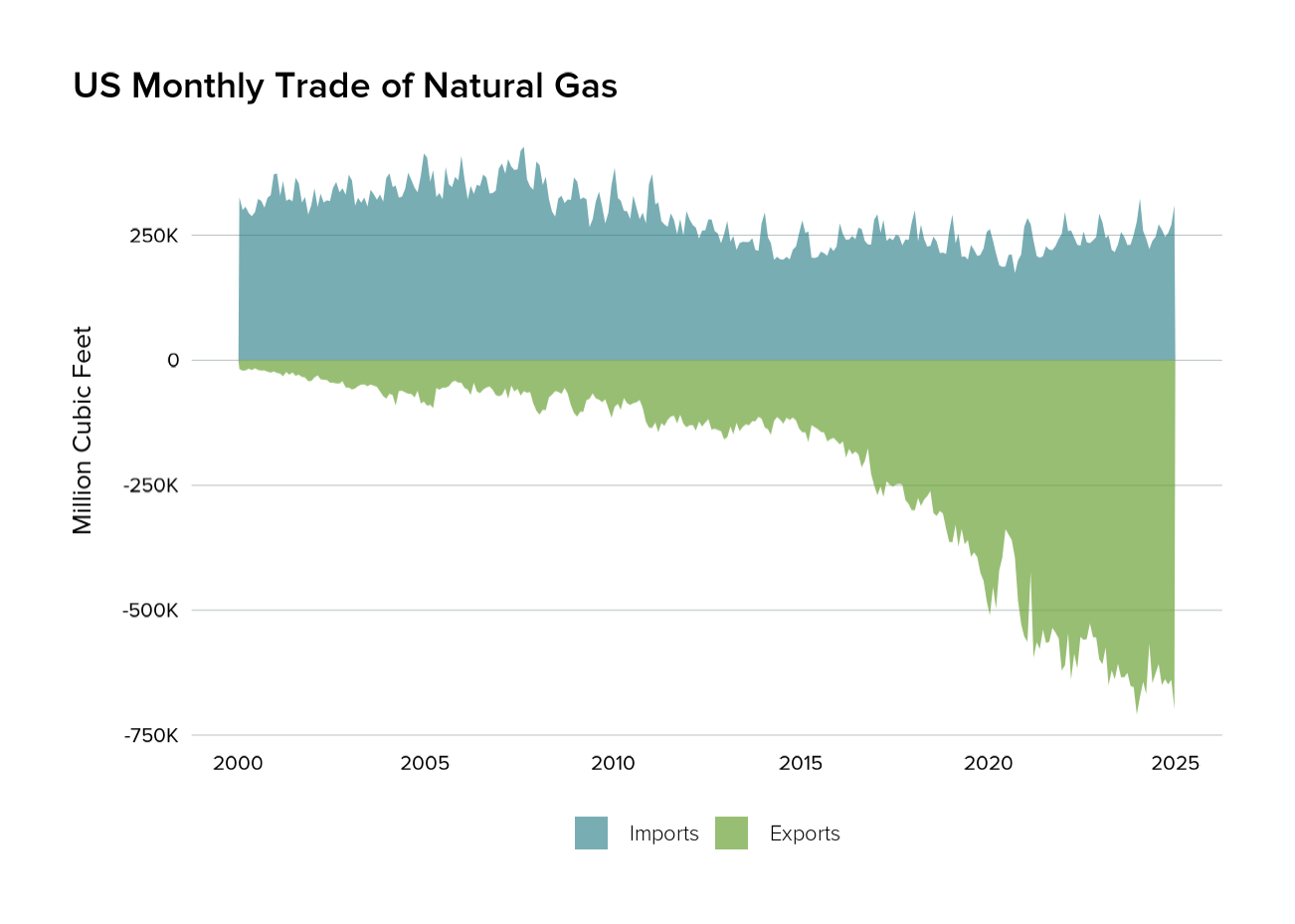

Policymakers laid much of the groundwork for this outcome through past industry-friendly decisions. In 2015, Congress repealed the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975 (EPCA), which had restricted the export of crude oil. Immediately, oil exports began to skyrocket. While EPCA had provisions that restricted natural gas as well, they were never implemented. Export of natural gas is instead regulated by the 1938 Natural Gas Act, which requires exports to be authorized by the Department of Energy. Sabine Pass, the first liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminal in the lower 48 states, was approved in 2011 and began exporting in 2016. Natural gas exports have grown markedly since then. By 2021, when a global energy shock created supply shortages in Europe, driving the global price of oil and gas up, a significant portion of domestic production was funneled abroad.

Figure 2.

Source: EIA, US Natural Gas Imports & Exports by State

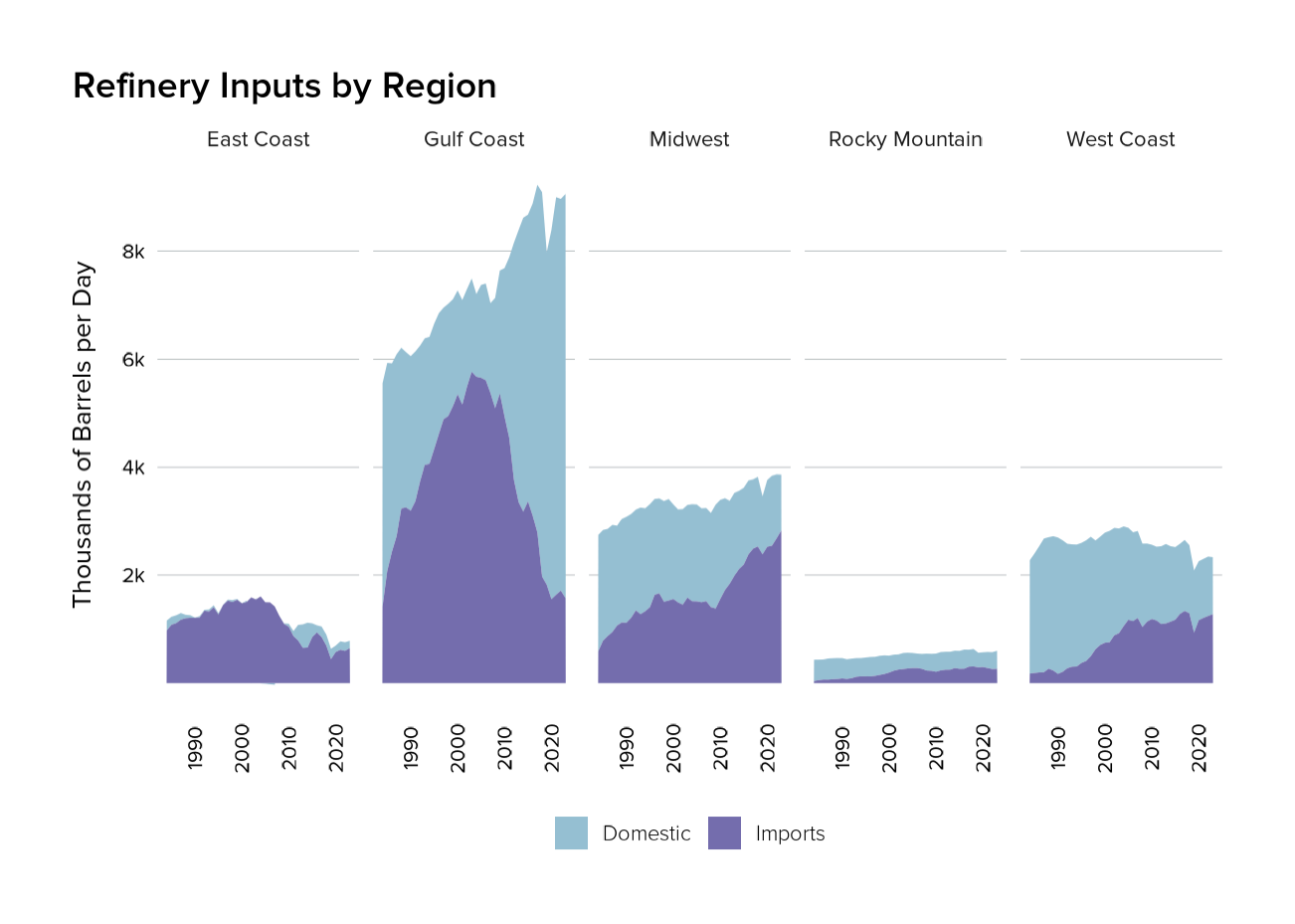

Differences in the qualities of crude oil also account for some of the discrepancy between US production and refining. US producers, benefiting from investments in fracking technology, primarily extract a light, low-sulfur (sweet) form of crude oil that is easier to process and thus trades at a premium on international markets. US refineries, on the other hand, process a mix (in aggregate) of this light sweet crude along with heavy, sulfurous (sour) oil. Heavy crude accounts for less than 5 percent of US production but 60 percent of imports. While there is a relative degree of regional variation in the grades of oil processed by refineries, imports remain essential to US refining across the board, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Source: EIA, Monthly Imports Report and Monthly Refinery Report

Thus far, US producers are showing little sign that they will take up the call to increase their production levels, as this risks lowering prices to unprofitable levels. The most recent Dallas Fed Energy Survey of oil and gas executives reports a remarkable degree of business uneasiness and policy uncertainty. The most glaring source of this uncertainty comes from the administration’s highly erratic trade policy. On March 3, Trump announced tariffs of 10 percent on Canadian energy, inflicting a direct tax on the primary input to US petroleum processing and consumption. The US imports nearly 5 million barrels of oil a day from Canada, making our northern neighbor far and away our largest external supplier. Mexico follows at a distant second, with around 500,000 imported barrels a day. Furthermore, Trump’s indiscriminate and unpredictable tariff announcements will increase costs, disrupt supply chains, and lower global demand, all of which bode ill for energy producers in the near term. It is unlikely that this environment will be conducive to long-term investments to transition domestic refining capacity away from import dependence. For the time being, US producers, refiners, and consumers remain tied to global markets.

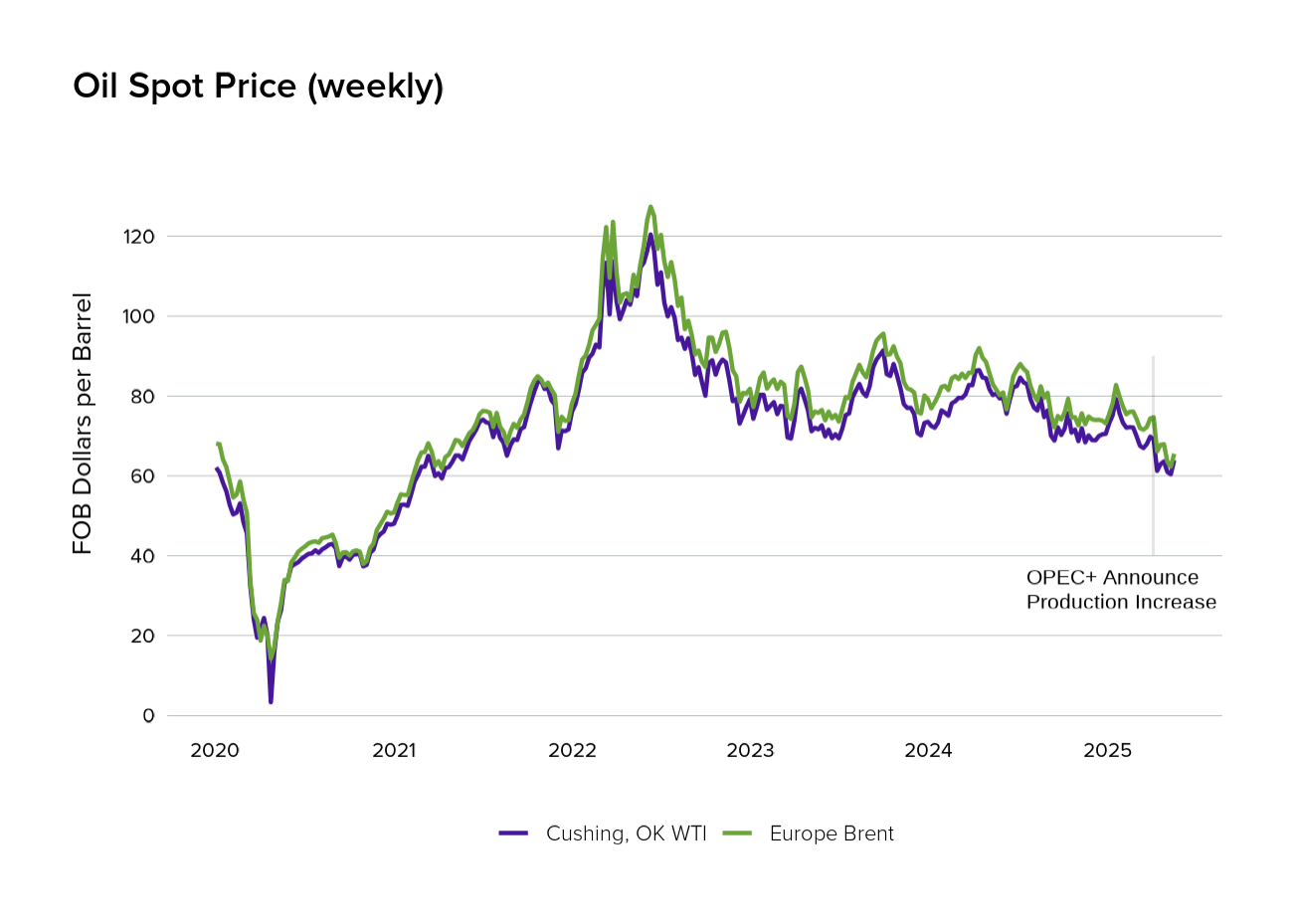

This integration is best evidenced when the oil-producing nations of OPEC+ increase production, leading to a drop in spot prices, as has recently occurred. On a spot market, traders pay for the delivery of a specific quantity of a product at a price posted at the time of sale. Spot prices are key not only because they inform the costs passed onto consumers further down the value chain, but also because they serve as break-even prices for producers and their shareholders, which means that changes in their level can inform production decisions. For example, the most recent Dallas Fed Energy Survey reported that among its sample of respondents, US shale producers, on average, require $41 per barrel to break even and $65 per barrel to profitably drill new wells. In April, crude oil prices on the US West Texas Intermediate spot market reached $60 a barrel.

Figure 4.

Source: EIA, Petroleum & Other Liquids, Spot Prices

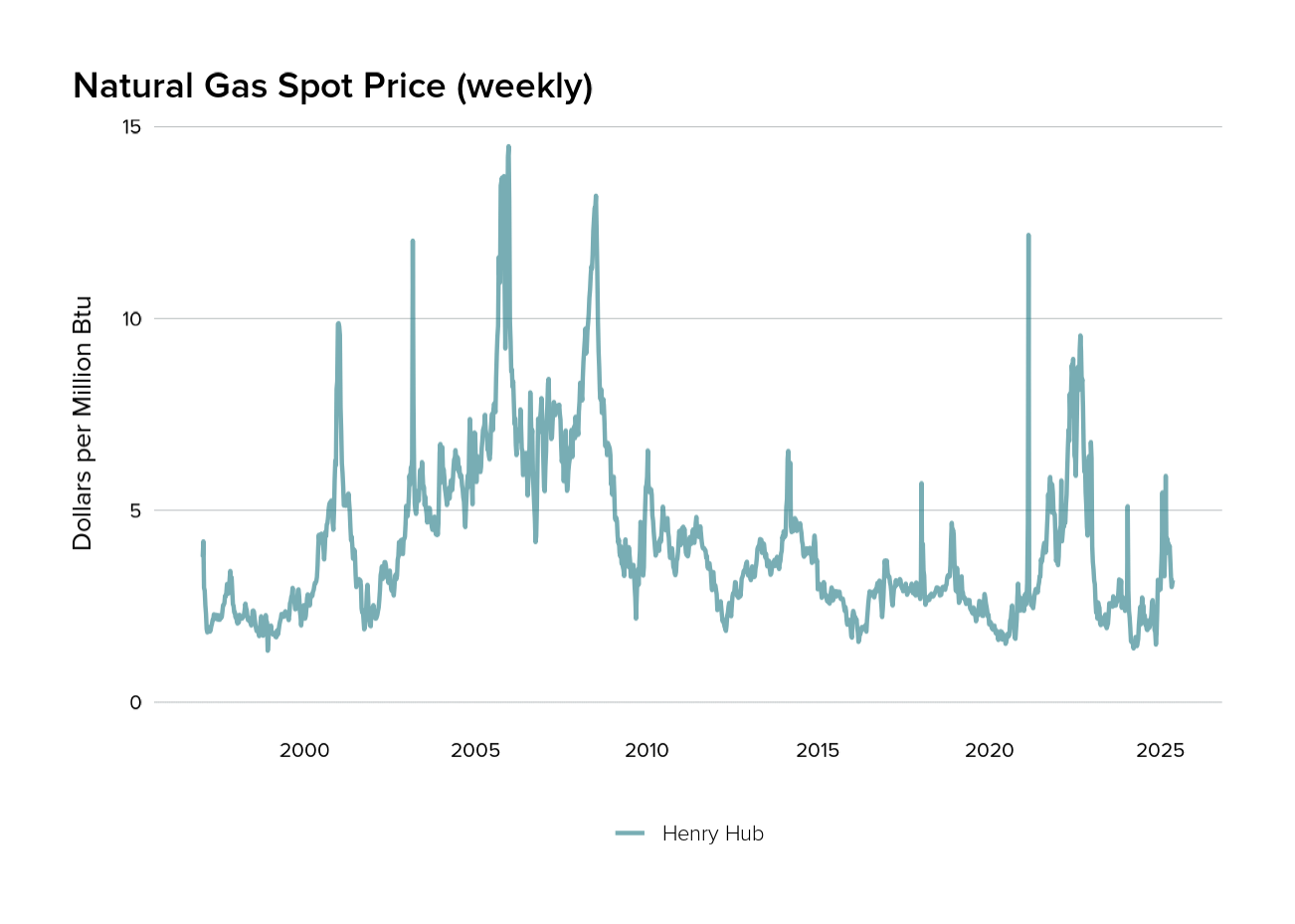

The increased global integration of US natural gas markets has impacts for US consumers, in addition to the effects on trade noted above. In particular, electricity markets in the US are structured such that power plants are dispatched to supply energy in order of their marginal cost. The highest marginal cost generator—often natural gas—sets the price that all electricity generators receive. As a result of this market structure, the spot price of natural gas, which is highly volatile, is consequential for consumers and producers of electricity alike.

Figure 5.

Source: EIA, Henry Hub Natural Gas Spot Price

The Composition of US Energy

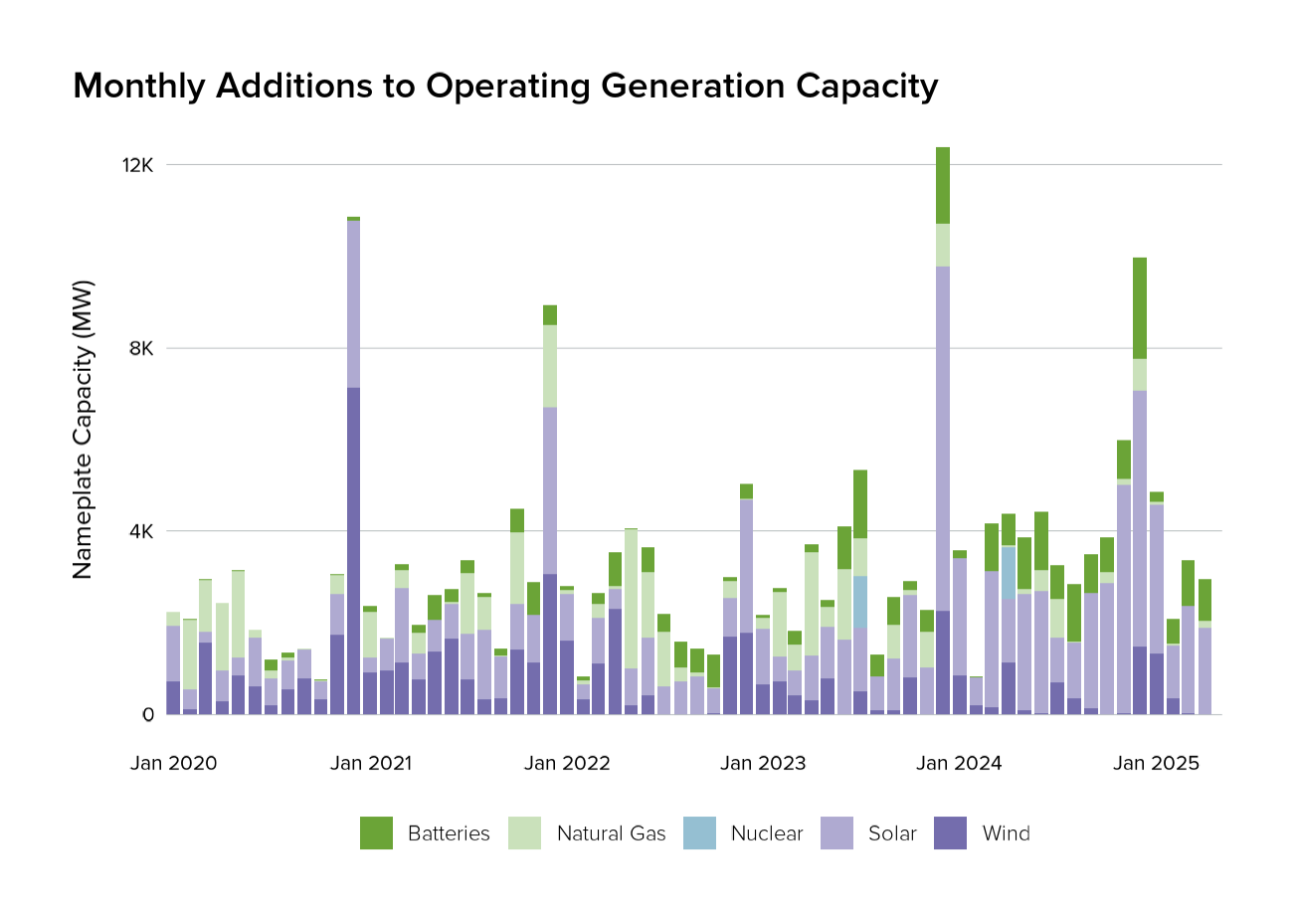

Acting as more than just systemically significant prices for consumers, oil and gas form the basis of US energy production and consumption. The US entered 2025 with more than 80 percent of energy production and consumption consisting of fossil fuels. At the same time, the past five years have marked the beginning of a notable shift in investment into renewable energy sources. Figure 6 below shows monthly additions to the inventory of operating generators, measured in terms of technology type and nameplate capacity. Solar leads the way in new capacity, and batteries have shown consistent growth since 2021. Additions of nuclear power remain minimal and sporadic, and growth of new natural gas capacity slowed down in 2024. Meanwhile, growth in wind power has shown a steady downward trend in additions since 2021. Since assuming office, Trump has maintained a consistent attack on efforts to transition away from fossil fuels by stretching his presidential authority to withhold allocated funds, reverse emissions regulations, and discontinue federally supported scientific research into climate change. His administration has directly targeted wind energy by revoking permits, terminating research funding, and blocking leases on federal lands. It remains to be seen to what degree the industry will withstand these challenges.

Figure 6.

Source: EIA, Preliminary Monthly Electric Generator Inventory

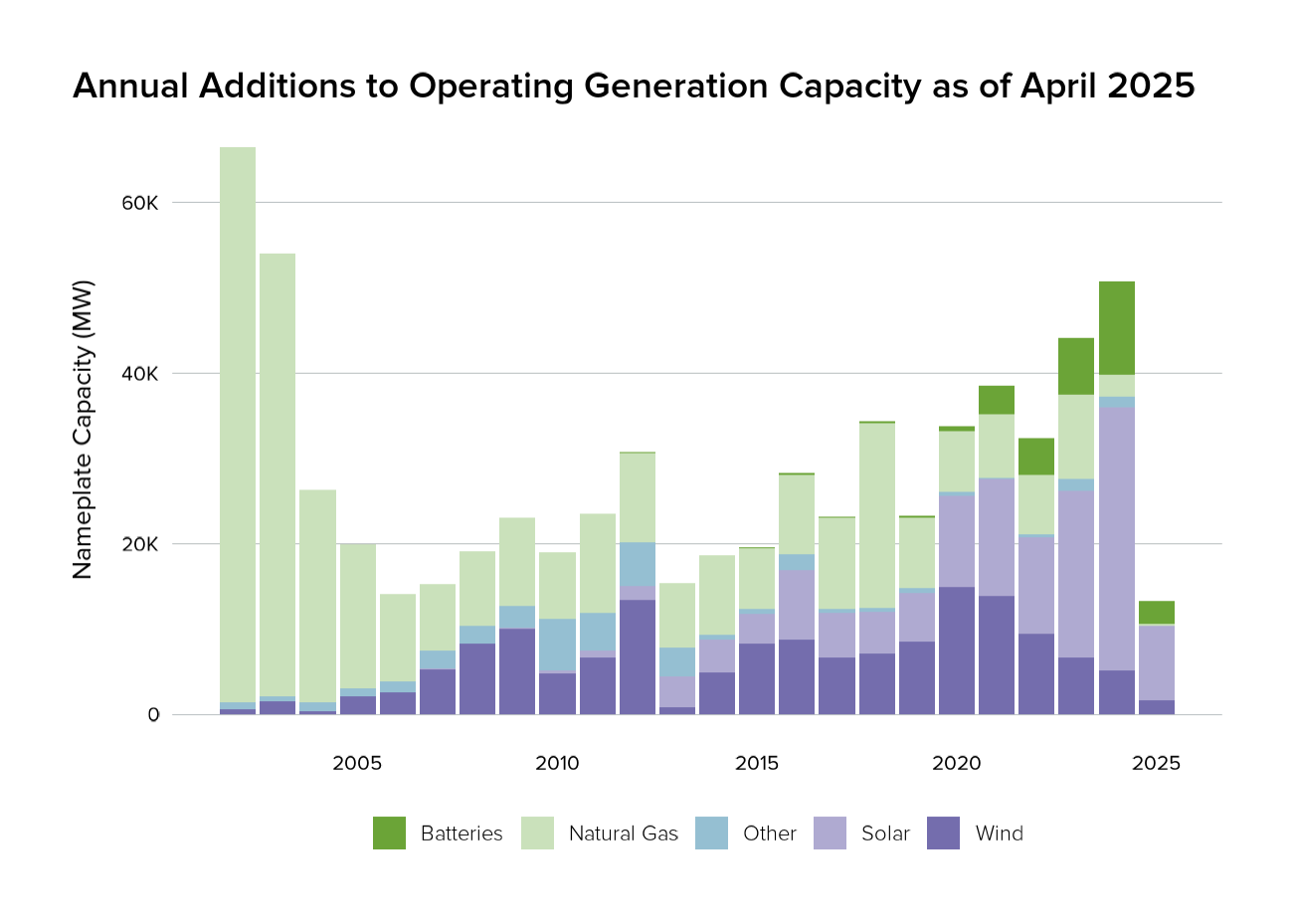

Despite increasing investment in wind, solar, and storage power over recent years, the levels of new capacity in these technologies remain below the heights of natural gas investment over the past two decades. Figure 7 below gives a picture of this longer view, providing annual totals for investment in nameplate capacity by technology type.

Figure 7.

Source: EIA, Preliminary Monthly Electric Generator Inventory

The period from 2022 to 2024 saw average annual growth rates of 65 percent in solar capacity and 60 percent in batteries, suggesting that the IRA had a palpable effect on investment in these renewable energy sources. The grant- and loan-making authorities provided by this act have already been significantly rolled back by the current administration. The ongoing budget reconciliation proceedings will determine the fate of many of the core tax credits provided by the IRA. While some Republican lawmakers indicated disagreement on the tax credits over the past few months, last week’s House vote showed no signs of GOP dissent to the harsh curtailment of the IRA’s core provisions.

The Trump administration’s first four months were tumultuous, sowing uncertainty across the energy landscape. But perhaps the clearest policy stance in this sector has been the hostility to renewable energy and climate science. The oil and gas industry is caught between expansionary sloganeering and deregulatory incentives on the one hand and the real cost pressures and immense policy uncertainty of the present environment on the other. Despite the United States’ ascension to world leader in oil production, the fantasy of US “energy dominance” remains divorced from the reality of US productive capacities and the depth of OPEC+ market share. Given the volatility of energy markets and the erratic policies of this administration, continued turbulence is all but guaranteed.