Why Unemployment Can Stay Low While We Fight Inflation

October 21, 2022

By Justin Bloesch

Job growth has been remarkably even across sectors, and measures of both labor market tightness and wage growth are already falling while the unemployment rate remains low. There is therefore little reason to think that today’s 3.5 percent unemployment rate is inherently more inflationary than it was in 2019.

Many economists, including within the Federal Reserve, are arguing that today’s 3.5 percent unemployment rate is below the “natural rate” of unemployment and needs to rise to help bring down inflation. However, the unemployment rate was 3.5 percent in 2019, when inflation was low and stable. What changed between then and now that the supposed “natural” unemployment rate went up?

Why the “Higher Natural Rate of Unemployment” Argument Doesn’t Add Up

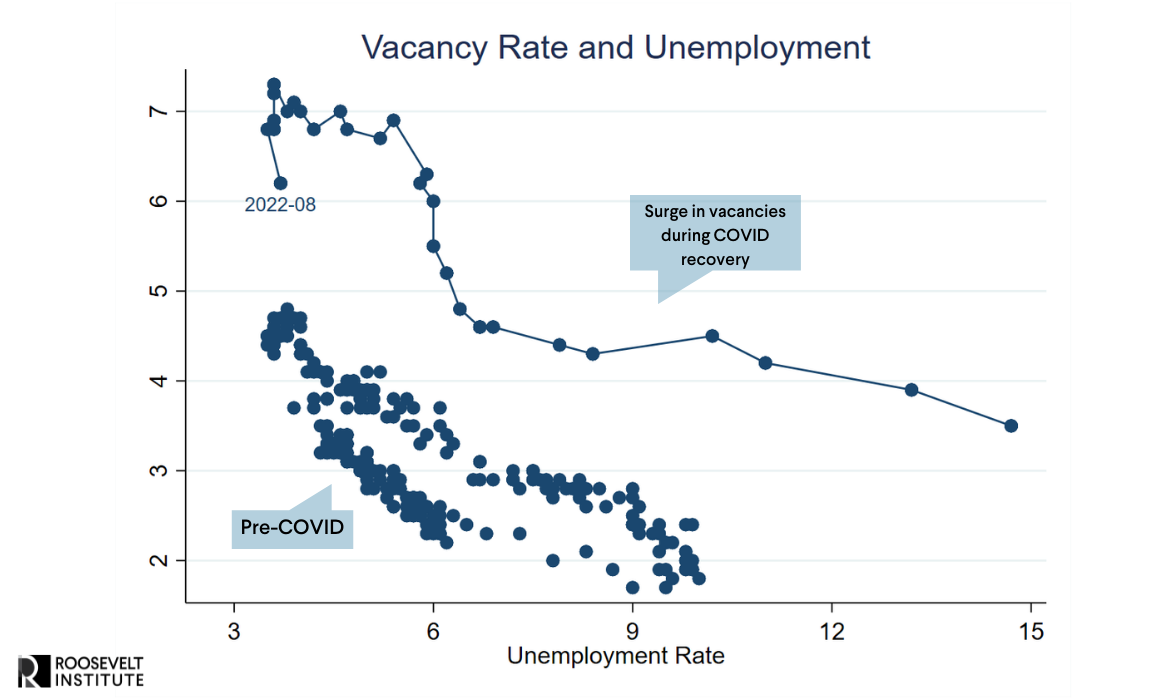

Some argue that what matters for the labor market’s contribution to inflation is the ratio of vacancies to unemployment (V/U), which is now very high (see Blanchard, Domash, and Summers (2022)). The argument is that if vacancies are very high relative to the level of available workers, then something must have changed in the labor market such that matching workers to jobs is less efficient. If workers cannot be matched to jobs as efficiently as before, then sustaining such low unemployment rates puts upward pressure on wages and requires more recruiting effort by firms, driving up costs and prices. Further, this argument maintains that vacancies cannot go down without unemployment rising, and so lowering the V/U ratio necessarily means that unemployment must rise to be consistent with low inflation.

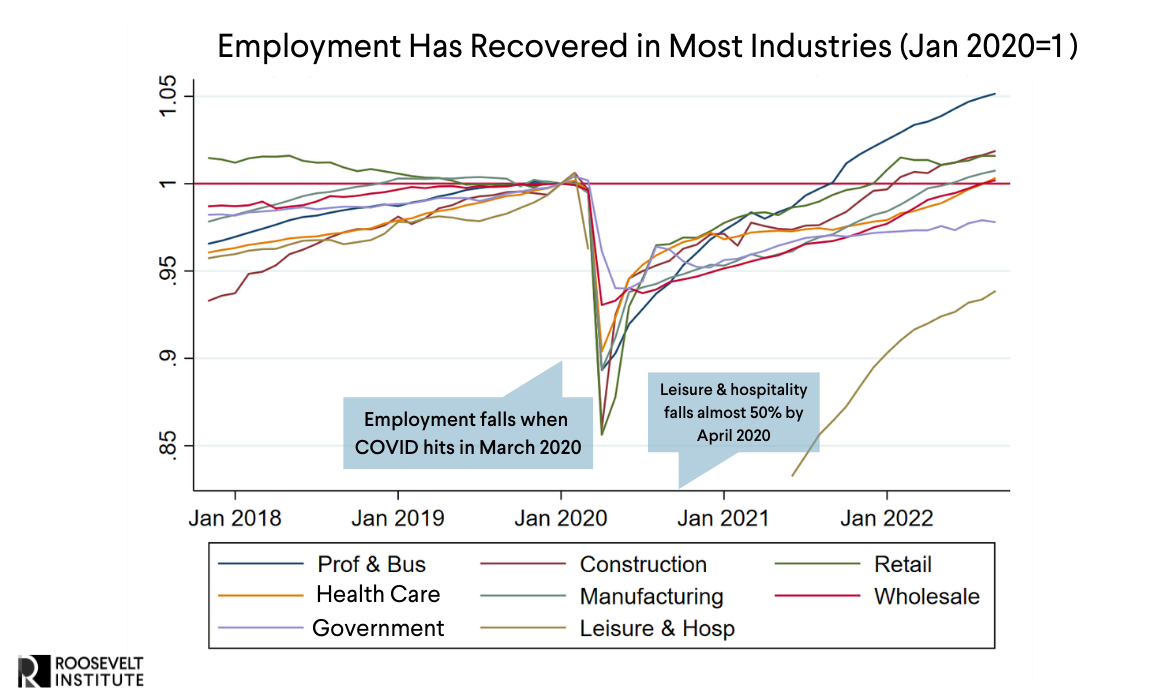

This story of inefficient matching should leave a trail of evidence other than high vacancies. The best corroborating evidence would be a rise in structural unemployment: If some sectors shrink and workers have sector-specific skills, then some workers may have a hard time reallocating into growing sectors that require different skills. While this may be an acceptable story for the early days of the pandemic, this story does not add up in the current context, as the recovery of employment has been strikingly even across sectors relative to pre-COVID employment levels.

Figure 1: Employment Growth by Sector, 2017-2022

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED Database

The only private employment sector that has seen major job declines is leisure and hospitality—down by over 1 million jobs (about 6.3 percent from the pre-pandemic peak)—but that story doesn’t fit with structural unemployment either. Demand for workers in leisure and hospitality has been searingly hot, and wages have grown by 15 to 20 percent in this sector over the last two years. If anything, falling employment in leisure and hospitality suggests that workers have gotten better, higher-paying jobs in other sectors. The only other sector with lower employment than before the pandemic is the public sector, which is down by around 2.5 percent.

This overall evenness of job gains differs markedly from the recessions in 2001 and 2008 and subsequent recoveries, where job growth in goods sectors vastly underperformed job growth in services, and even then the extent of structural unemployment was overstated.

The Labor Market Is Cooling While the Unemployment Remains Low

The better explanation for a temporarily high V/U ratio, and the overall high level of churn in the economy, is just that the economy was rapidly emerging from the pandemic. Many workers did lose their jobs and took jobs in new sectors, and demand for labor was both high and growing rapidly. However, as the economy shifts to a slower pace of growth, it is likely that recruiting activity can fall without triggering layoffs. Past evidence showing that unemployment rises with falling vacancies may not be applicable in this cycle: The economy has not shifted from high unemployment to a tight labor market so rapidly in periods for which we have data, and evidence is already showing the vacancy rate is starting to fall while the unemployment rate remains low.

Figure 2: Unemployment and JOLTS Vacancy Rate, 2001-2022

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED Database

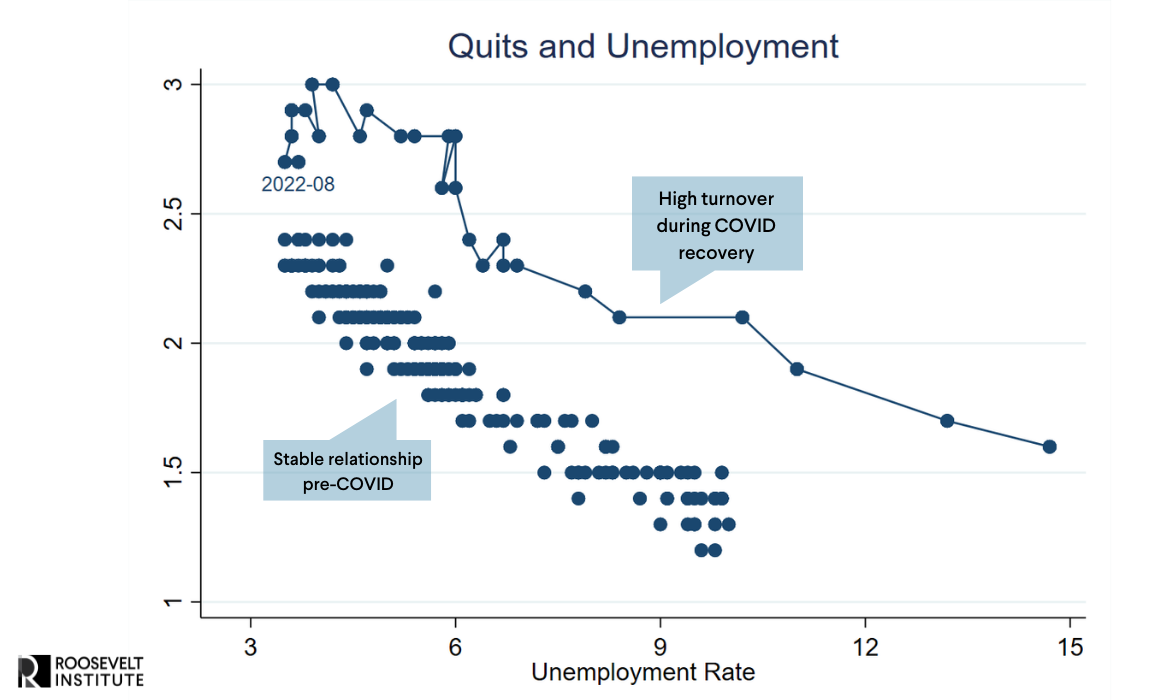

However, vacancies may not be the best way to measure labor market tightness. As many commentators have noted, long-term trends in the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) vacancy series cast doubt on whether the level of the vacancy rate is comparable over long periods of time. For example, using data from JOLTS, there used to be around 1.3 vacancies per quit in the early 2000s. By 2019, there were around 2.3 vacancies per quit. As of 2022, there were 2.6 vacancies per quit. Given the large literature showing that job-to-job transitions are an excellent predictor of wage growth, it appears that quits is likely the better measure of demand for labor that isn’t confounded by long-term trends.

Figure 3: Unemployment and JOLTS Quits Rate, 2001-2022

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED Database

When looking at the path of quits and unemployment, we see an even more benign story. Prior to COVID, there was a stable and negative relationship between the quits rate and unemployment rate, with a slight bend: As the unemployment rate gets low, the slope of quits to unemployment steepens. During COVID, there was a big shift of this curve up and to the right. Over 2021 and early 2022, the labor market became much tighter, and quits rose sharply as unemployment fell. As of early 2022, quits peaked at around 3 percent per month. However, since then, quits have fallen to 2.7 percent, while the unemployment rate has remained at a constant level, bringing the current data closer in line with the historical relationship between quits and vacancies. If you were to do a similar analysis as Blanchard/Domash/Summers using quits, you would conclude that there doesn’t seem to be much of a structural shift at all.

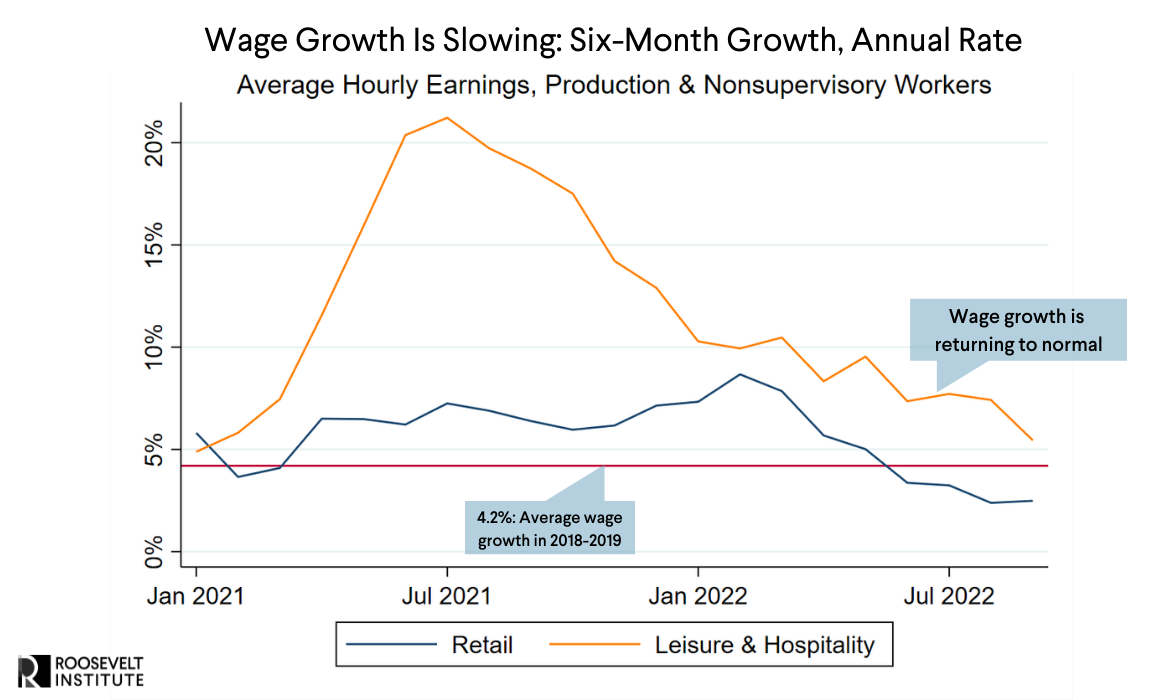

On the wages front, we already are seeing some effects of falling labor market tightness: Wage growth is dramatically slowing in the low-wage sectors of retail and leisure and hospitality, where wages are particularly sensitive to labor market tightness. For production and nonsupervisory workers in these sectors, the growth rate of average hourly earnings has fallen by half since early 2022, and even more since the peak wage growth during the pandemic for leisure and hospitality. Given that workers typically leave these sectors if demand is high in better-paying sectors and vice versa, slower wage growth in retail and leisure and hospitality suggests that the labor market is already starting to cool.

Figure 4: Wage Growth by Sector, Production & Non-supervisory Workers

Source: St. Louis Federal Reserve FRED Database

Conclusion

The labor market is definitely tighter than in 2019: Quits and vacancies are higher, and the unemployment rate is about the same. Labor supply is also lower due to lower immigration, accelerated retirements, and long-term health effects of COVID.

But the labor market as of October 2022 isn’t that much tighter than it was in 2019. Employment growth has been remarkably even across sectors, and slowing wage growth in low-wage occupations confirms further that tightness is falling. There is thus little reason to think that today’s 3.5 percent unemployment rate is inherently more inflationary than it was in 2019.

While further lowering the quit rate and the pace of wage growth will likely help bring down inflation by some amount, not much has changed to make one conclude that the unemployment rate consistent with low inflation, the so-called “natural rate,” is higher than before. Instead, it looks increasingly possible that the labor market can return to a strong but not overheating equilibrium, giving time for supply-side issues to be resolved and bring inflation back down.