Building a Vision for Universal Public Childcare: Principles for a Childcare System That Works for Workers and Families

July 21, 2025

By Lena Bilik, Mary Beth Salomone Testa, Suzanne Kahn, Nina Dastur, and Meredith Loomis Quinlan

This report is published in partnership with Community Change and Economic Security Project.

This is a web-friendly preview of the report.

Report Highlights

Executive Summary

The current early childhood care and education (ECE) system in the US is broken. Families struggle to access and afford ECE, and ECE providers across the workforce struggle to get by on chronically low wages. Half of families live in a childcare desert. At the same time, the ECE field faces a growing threat of corporate capture and private equity takeover. Some states are also seeing a push toward deregulation. The US needs bold, transformative public investments to create a public, universal ECE system that can meet the needs of families.

Over the past year, the Roosevelt Institute and Community Change hosted a series of conversations with a group of parents, childcare providers, and grassroots organizers to explore a proposal for a universal public ECE system. The conversations deliberately raised and worked through tensions and disagreement among existing stakeholders over how to imagine such a system. In particular, we discussed how to ensure that current stakeholders in the system—especially workers—do not get left behind in a transition to a public ECE system.

This paper offers a forward-looking framework to join ongoing conversations to imagine a truly public, universal ECE system. ECE providers we spoke with know that the system is broken and needs to be transformed and that a shift to a public universal system would involve trade-offs because of the entrenched interests established by the current system. Informed by and reflective of our conversations as well as our examination of other ECE systems around the country and around the world, this report proposes a public, universal ECE system that is affordable, coordinated, safe and high-quality, and inclusive and culturally competent. It proposes a system that would have an affirmative obligation to build out more supply and capacity; make ECE jobs good jobs with collective bargaining rights, a thriving wage, and good benefits; and include robust stakeholder engagement and transition support for small, independent providers to be a part of the new system.

The public system we propose rests on supply-side investments, where the federal government provides funding directly to providers and programs through grants and contracts—instead of providing subsidies to families and leaving them to identify and secure care on their own. In many ways our proposal is structurally similar to the existing Early Head Start program, with consistent high quality standards and the ability for care to be provided both by public providers directly as well as by small homes and centers that contract with the state and become nonprofits, or join nonprofit networks. Each of the components of our proposal is necessary to build a public childcare system that expands the ECE workforce and ensures adequate space and staffing levels alongside the quality required to meet the needs of all children and families, all while protecting public funding for ECE from corporate capture. We believe a truly high-quality, universally accessible system will build an engaged constituency of supporters that will sustain it.

Our proposal aims to build a public infrastructure of care that is sustainable, affordable, high-quality, and universally accessible first and foremost. The system should meet the needs of families, including but not limited to: the needs of children with disabilities; the financial needs of families; the need for full-day, full-year care; the need for high-quality and age-appropriate youth development, care, and education; and the need for young children to have attentive, consistent adult relationships. We also envision ECE that above all provides safe, nurturing learning opportunities for all children. In order to build a public system that does all of that, we must offer ECE providers family-sustaining wages and benefits at parity with K-12 educators. We must understand such an ECE system as sitting within a broader care system that, ideally, includes one year of paid parental leave as well as comprehensive care beyond ECE including universal preschool, after-school, and summer care. We hope that this paper advances the conversation to transform the ECE system toward an accord that the field can mobilize around.

Introduction

The US is in the midst of an undeniable childcare accessibility and affordability crisis. In 2023, 69 percent of households with children under age six had both parents in the workforce (US Census Bureau 2023). Thus, the vast majority of parents need early childhood care and education (ECE). Accessible, affordable, high-quality ECE is a necessary part of a healthy economy and crucially beneficial and foundational for positive childhood development and well-being. The benefits children see from high-quality ECE often last into kindergarten, middle school, high school, and beyond (Schoch et al. 2023). Yet half of American families live in childcare deserts (Malik et al. 2018), while the average annual price of childcare exceeds families’ costs of transportation, food, health care, or housing in most parts of the country, putting formal care financially out of reach for low- and middle-income families alike (Child Care Aware 2023). The US Department of Health and Human Services defines unaffordable childcare as more than 7 percent of income; by that standard, about 43 percent of families with young children who pay for childcare pay unaffordable rates (Ross and Andara 2024). As a result, the US economy loses an estimated $122 billion a year due to childcare challenges (Bishop 2023).

Former Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen called our current ECE system “a textbook example of a broken market” (Yellen 2021). Markets alone do not provide sufficient access to ECE. ECE is high-cost and labor-intensive, with low profit margins (Schneider and Gibbs 2023). Wages for ECE providers remain lower than in most other industries and far lower than those of educators who teach older children in the K-12 system, because providers cannot raise wages without increasing prices for families beyond what they can afford. Thus ECE wages remain too low to attract enough providers, leading to serious supply shortages.

A functioning ECE system will require significant and sustained public investment to solve this market failure and create a truly public ECE system for all. We are far past due for a shift from framing ECE as a problem for the private market and limited welfare funding to solve, to considering it a universal good for all children and families. Indeed, largely because of temporary COVID-era federal investment, we have seen unprecedented state and local ECE innovations in recent years. The federal government invested $52 billion to supplement the ECE industry and support families that allowed states to stabilize operations for 220,000 childcare providers, lower childcare costs for 1 million children, increase compensation for more than 710,000 childcare workers, and create 385,000 new childcare slots (ACF 2024). But states face major sustainability challenges now that that onetime relief funding has expired. While some states have used their own revenue to fill in these lost funds to good effect, others are instead loosening ECE regulations, increasing staff-to-child ratios, or decreasing training requirements in order to deal with the low supply of ECE (Mader 2024a). Private equity involvement is also a looming trend in the sector, with large for-profit childcare chains and franchises growing in prominence in recent years (Lynch and Su 2024). Deregulation and corporatization are not solutions; lower ratios lead to lower-quality care and safety risks for children, and early childhood education should not be subject to the profit motives of private equity.

A functioning ECE system will require significant and sustained public investment to solve this market failure and create a truly public ECE system for all. We are far past due for a shift from framing ECE as a problem for the private market and limited welfare funding to considering it a universal good for all children and families.

In the face of these trends, there is broad agreement that we need bold, transformative public investments in childcare. Nevertheless, the ECE field itself has historically experienced tensions and disagreement over how to shape such an investment. These tensions often arise when considering how to craft an accessible, responsive, universal care infrastructure from current fragmented care programming. Among the chief issues we aim to reconcile is ensuring an ongoing role for the current workforce, which is overwhelmingly women and people of color, some of whom are small-business owners who operate private home-based family childcare (FCC) or small independently owned centers. These small-business owners have found ways to make ECE a meaningful career and meet families’ needs despite operating in a chronically underfunded and under-resourced sector. Though providers agree that the system is broken—low access, low pay, and low supply are undeniable—many of them also understandably fear that large structural changes to the system could endanger their livelihoods, disrupt their autonomy, and shut them out of a system they have invested themselves in for their entire careers. Many communities also lack trust in the government and faith that public systems can truly meet the needs of diverse communities and families on a large scale, in part due to a history of chronic racial inequity and underfunding in large public systems like the K-12 educational system (Century Foundation 2020; Baker, Di Carlo, and Weber 2024).

The genesis for this paper and the accompanying conversations with parents, providers, and organizers came from an understanding of the inadequacy of the current fragmented system and a hope to offer a responsive, forward-looking framework that could join broader conversations about how to imagine truly public, universal ECE born out of the strengths of current programs but divorced from their current limitations and vulnerabilities. In particular, the growing threat of corporate capture and private-equity takeover of ECE also drove this project and paper. Our proposal sets clear principles and guardrails around the receipt of public financing so that corporate interests cannot pillage public funding. Given historic disinvestment in this field, we also recognize that trying to protect against that pillaging necessarily implicates questions about the types of programs that should receive public funding. ECE providers we spoke with know that the system is broken and needs to be transformed and that a shift to a public universal system would involve major trade-offs because of the entrenched interests established by the current system and its historical precedents.

Informed by and reflective of those conversations, as well as our examination of other ECE systems around the world, this report proposes a public, universal, equitable ECE system that includes a “just transition” for the current workforce, especially those small providers who are critical assets in their communities. The “just transition” is necessary because an ECE system will only be able to serve all children and families if it has a sufficient workforce, including the current workforce who are already experts in this work along with a massive expansion of the field. We propose a public ECE system that would attract enough workers to staff the universal programs by offering current and future providers the workplace dignity, thriving wages, and benefits they deserve. This framing resonated with more of our stakeholders. As one provider put it, “We’re doing a public good but not getting publicly compensated.”

This proposal does not fully detail all of the operational components that would be required to enact it in legislation but instead outlines a structure that meets the principles identified by our stakeholders as well as our own goals for a public ECE program that addresses current countervailing market and political forces. We hope it is the start of further work exploring how legislation could best operationalize these principles.

A universal, public ECE system should have the following qualities, which are explored in detail in Part IV of this paper:

- Affordable

- Free or accessed through a nominal base fee for all families

- Universal

- Universally accessible, with ECE as a legal right for all children

- An affirmative obligation that the government ensure sufficient public spots through supply-side investments

- Coordinated and Streamlined

- Non-fragmented governance structures

- Federally administered through state and/or regional infrastructure to support implementation and expansion

- A Thriving, Diverse Workforce

- Thriving wages—more than just living wages—and benefits for a valued and well-resourced workforce

- A direct payment model through grants and contracts that covers providers’ labor and other fixed costs

- The right to worker organizing and collective bargaining

- Inclusive and Culturally Competent

- Culturally and linguistically competent care

- Universally accessible services for early intervention and for children with disabilities

- Safe and High-Quality

- Child-centered safety and quality with consistent, evidence-based guidelines built with parent, family, and provider input

- A “Just Transition”

- A plan to transition the current workforce into the universal system fairly and without disruptions

Other countries show us that it is popular and more cost effective to institute care on a continuum that includes paid leave and universal prekindergarten (UPK). Paid family leave for one year also accounts for the realities of infant care. We therefore recommend a universal ECE system that exists within a broader care system that, ideally, includes one year of paid parental leave as well as comprehensive care beyond ECE including universal preschool, after-school, and summer care (Edwards 2025).

When we describe our proposal as a “universal” and “public” ECE system, we mean a system that is sufficiently resourced with government funding to offer affordable, high-quality childcare for all families. We imagine strong labor protections so that all ECE providers can collectively bargain and in doing so expand upon the wins of current childcare unions to ensure a just transition, a sufficient supply of workers, and the ongoing sustainability of the system. We mean a system that has an affirmative obligation to create enough supply to meet parents’ needs, so that childcare is available as a public good for all families. In our vision, universal ECE would allow public programs as well as licensed nonprofit private providers that contract with the government to offer care. Consistent and equitable quality frameworks and guidelines should allow for a variety of pedagogical approaches. This would all be a major shift from the way the US has operated for decades, so to support equitable access to contracting opportunities, robust resources and technical assistance would be made available for current private providers—such as small, independently owned programs—to transition their capacity into the new system. It would also require robust feedback structures so that parents and providers can be a part of the rollout and continued operation of the system.

Choice and Pluralism

Proposals for a universal ECE system necessarily implicate questions surrounding the importance of parent and provider choice. In conversations within the field, this debate has mainly revolved around the extent to which choice of care setting is prioritized for and by parents, along with providers’ choice to operate as small for-profit business owners and exercise autonomy around other programmatic features, including choice of curriculum. We balanced our consideration of these important values, in both our conversations with stakeholders and the development of structural recommendations informed by them, with two principles: (1) an infrastructure of care at scale that is accountable to taxpayer investment (i.e., that is economically efficient) would not permit unlimited choice available to any individual family; and (2) the threat of private profiteering off of public investment—evidenced most particularly through the expansion of private equity–backed ECE programs but also in the growing movement of states to redirect public financing of K-12 education to vouchers—undermines the role of government in providing public goods and reinforces destructive structural inequities that limit the choices of parents and small-scale providers in other important ways. The framework we propose supports a range of social, emotional, developmental and intellectual options while promoting and protecting the conception of early childhood education as a public good that the state should provide, recognizing the trade-offs that this requires.

Parental Choice

This paper does not presume to know the kinds of settings that are most effective for all families. Given that, for too many families, their “choice” is constrained by cost and availability, it is difficult to know the care arrangements that parents would select for their children if affordability and accessibility were not an issue. What we do know: In fiscal year 2021 (the latest year for which data is available), out of the 1.4 million low-income children under the age of 13 receiving a childcare subsidy through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), 73 percent were cared for in a childcare center, 7 percent in group homes, 14 percent in FCC homes, and 1 percent in the child’s own home (ACF 2024a). A survey of families with at least one weekly nonparental care arrangement (subsidized or not) found that 66 percent were attending day care centers, Head Start programs, preschools, prekindergartens, and other center-based care; 34 percent were cared for by a relative; and 17 percent were cared for in a private home by a nonrelative (Hanson, Brobowski, and McNamara 2024).1 As of 2023, the number of childcare centers has rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, while the number of FCC homes continues to trend downward (Child Care Aware 2023).

A Bipartisan Policy Center national survey revealed that, although cost is an important factor, parent choice around ECE setting can be complex. The survey found that, though many parents prefer formal care, some prefer informal care regardless of cost. Data from the National Household Education Surveys (NHES) program in 2023 found that reliability of the childcare arrangement was the factor most often rated as “very important,” followed by available times for care and qualifications of staff. The same NHES survey found that, among parents who searched for childcare, 72 percent reported that they had at least a little difficulty finding care, citing cost and lack of open slots most often as the primary reason for the difficulty (Hanson, Brobowski, and McNamara 2024).

Given the limitations of what we can know from data about parent choice in a broken system, we also considered the ways that K-12 voucher initiatives that direct some public funding premised on prioritizing parent choice have impacted universality, enrollment, funding, and quality of public K-12 education. Research shows, for example, that voucher programs do not improve student achievement and generally put large new demands on state and local budgets, increasing the cost of educating children in public schools (Wething 2024). Unmitigated school-choice policies can also increase segregation (Ukanwa, Jones, and Turner 2022). Avoiding negative externalities such as these drove our decision not to include a voucher system in our proposal. In order to build a truly public system and treat ECE as a public good, we are focused on how to build a public infrastructure of care that is sustainable, affordable, high-quality, and universal first and foremost. We can build a public system that meets the needs of children and their families, including but not limited to the needs of children with disabilities; the financial needs of families; the need for full-day, full-year care; the need for high-quality and age-appropriate youth development, care, and education; and the need of young children to have attentive, consistent adult relationships in their ECE programs. And, of course, a universally available public system does not preclude parents from choosing to utilize informal care arrangements or private options.

Provider Choice

The question of provider choice and autonomy has been a tension when stakeholders discuss how to improve our ECE system, specifically with small, independently owned ECE programs. Especially for women of color, childcare has provided a pathway to entrepreneurship and small business ownership. Even though parents’ ability to afford care and low reimbursement rates significantly constrain providers’ programming and financial viability, some owners view potential regulatory requirements as impinging on their autonomy to operate their businesses. Securing transformative increases in public funding for childcare is the underlying premise for our recommendations, not only to subsidize care universally but also to raise provider wages significantly and finance benefits to promote financial security for ECE workers, relieving owners of the limitations imposed by cost constraints. To ensure accountability and high-road labor practices across the program, the government will oversee receipt of those funds and require that providers shift their business models. Though our proposal only considers public and nonprofit programs eligible for public funding, we address the implications of this for the current workforce as comprehensively as possible in our “just transition” section, in which we lay out suggestions to effectively ensure that all current providers, including small independently owned programs, can be brought in to the public system and receive pay increases and improved worker benefits as a result.

This report

- summarizes the values and priorities of the stakeholders we interviewed;

- recommends the key defining characteristics of a public, universal ECE system to spark a broader conversation in the field, with the long-term goal of empowering the field to mobilize behind the need for public universal ECE;

- addresses the need for a “just transition” framework to ensure the current workforce is brought along in a shift to a public ECE system, for both worker justice and system capacity reasons; and

- highlights considerations and insights from the ECE systems in a selection of US states, localities, and other countries.

State and local organizing has been instrumental to secure new resources to address the childcare crisis, and a great deal of parent, provider, and grassroots community organizers have pushed their states to systemically reform their ECE systems. Many of those organizers shared their experiences and perspectives from those efforts to inform the ideas in this paper, and our proposal builds off the foundation established by these movements.

In our current moment, we recognize that calling for a massive federal investment to build a universal childcare system may seem naive or ignorant of the political vulnerabilities that a federal system would create. We have struggled with these questions, but we ultimately believe that the inequities across our current system demonstrate why a federal role will be essential to find bold, sustainable solutions that chart a path toward a system designed to meet the needs of all parents and workers. Such a role can only be played by a stable, democratic, and trustworthy federal government, which is what we must all be working toward daily. To power that fight, it is critical we remember what such a government could deliver: in this case, an effective, universal childcare system that meets the needs of children, families, and providers.

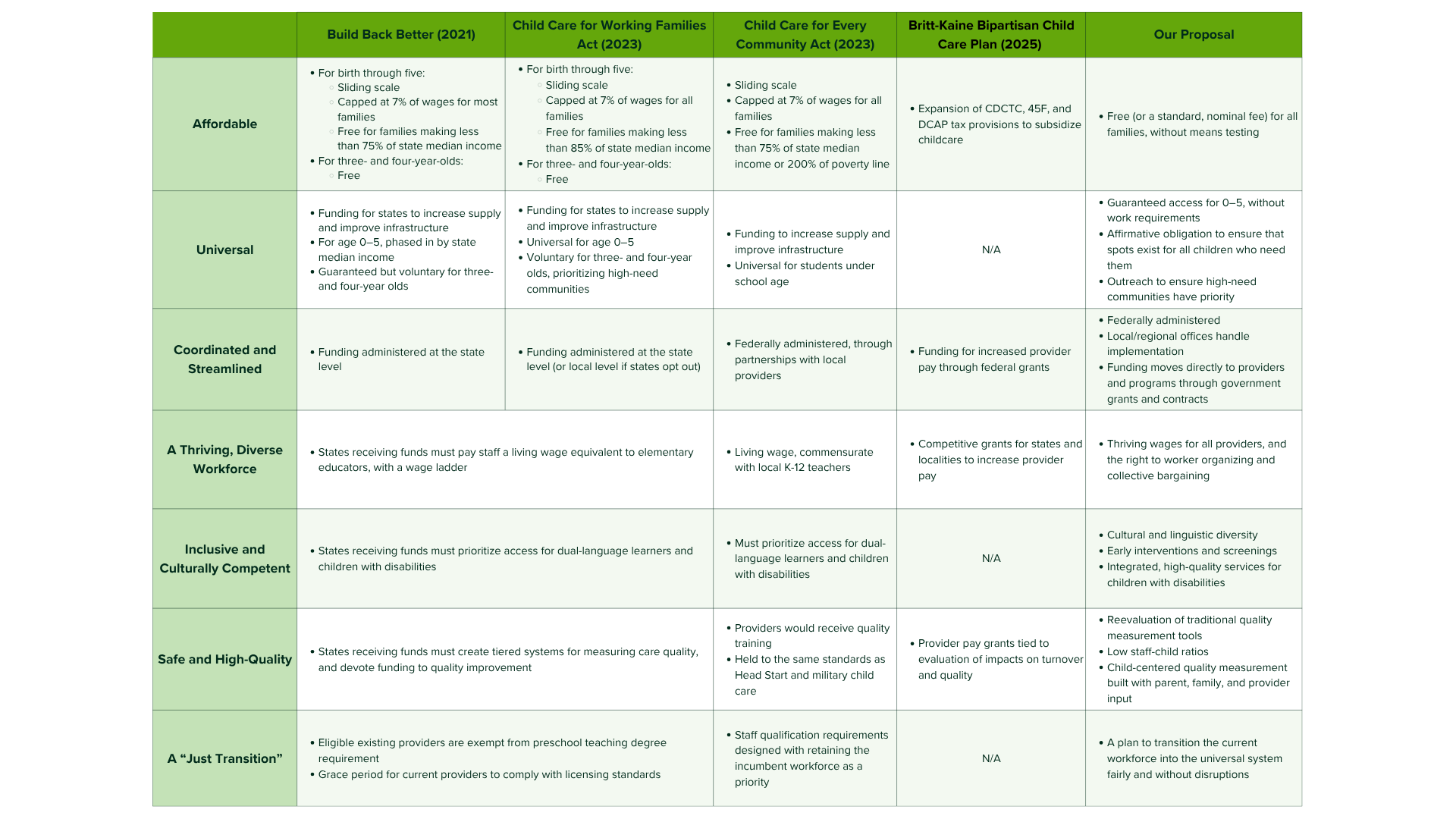

Table 1. Evaluating Childcare Proposals Using Principles of a Public Universal System

Read Footnote

These percentages add up to more than 100 percent because some families have multiple care arrangements.↩

Suggested Citation

Bilik, Lena, Mary Beth Salomone Testa, Suzanne Kahn, Nina Dastur, and Meredith Loomis Quinlan. 2025. Building a Vision for Universal Public Childcare: Principles for a Childcare System That Works for Workers and Families. New York: Roosevelt Institute.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Economic Security Project for their partnership and support on the work that went into this report. The authors also thank Melissa Boteach, Katherine De Chant, Ross Fitzgerald, Ruth Friedman, Erica Gallegos, Julie Kashen, Andrea Paluso, Alexandra Patterson, Natalie Renew, Yesenia Robles-Brown, Noa Rosinplotz, Cathy Sarri, and Aastha Uprety for their substantial feedback and contributions. We also thank the early childhood stakeholders we spoke to for this project for their invaluable wisdom. Any errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies are the authors’ alone.