Raising Wages through Sectoral Bargaining

February 15, 2024

By Alí R. Bustamante

"Despite high rates of wage growth over the past two years, the stagnant federal minimum wage and declining rates of union density have contributed to the suppression of average real wages for many Americans."

Introduction: The Need for Progressive Wage-Setting Mechanisms

The erosion of the real value of the minimum wage in the United States was a problem before the pandemic and has only gotten worse during recent years. Despite high rates of wage growth over the past two years, the stagnant federal minimum wage and declining rates of union density have contributed to the suppression of average real wages for many Americans.

In light of these trends, policymakers should look to sectoral bargaining as a critical tool in raising wage floors and ensuring that workers are fairly compensated.

American workers’ compensation is fundamentally shaped by two legal frameworks: minimum wage laws and collective bargaining rights. The inadequacies and limitations of existing labor laws have played a crucial role in depressing wage growth. The failure to regularly adjust the federal minimum wage, coupled with the inadequate expansion of state-level minimum wages, has led to a substantial erosion of real wage floors. At the same time, low levels of union membership have taken collective bargaining off the table for most workers. Without the collective power of unions, individual workers face significant challenges in negotiating for better pay and conditions, exacerbating the wage stagnation problem.

To reverse this trend, there is a pressing need for reforms that include regular adjustments to the federal minimum wage and stronger support for collective bargaining. In addition, sectoral bargaining legislation can offer a nuanced and targeted approach to wage setting where wages have eroded the most.

Stagnant Minimum Wage and Weakened Unions Depress Wage Growth

Minimum wage laws establish the wage floors for the majority of American workers, dictating the lowest wage rate employers can legally pay. The federal minimum wage, set by the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, currently stands at $7.25 per hour. This rate, which was established in July 2009, has not kept pace with inflation or productivity gains, leading to a significant real wage erosion (Baker 2020).

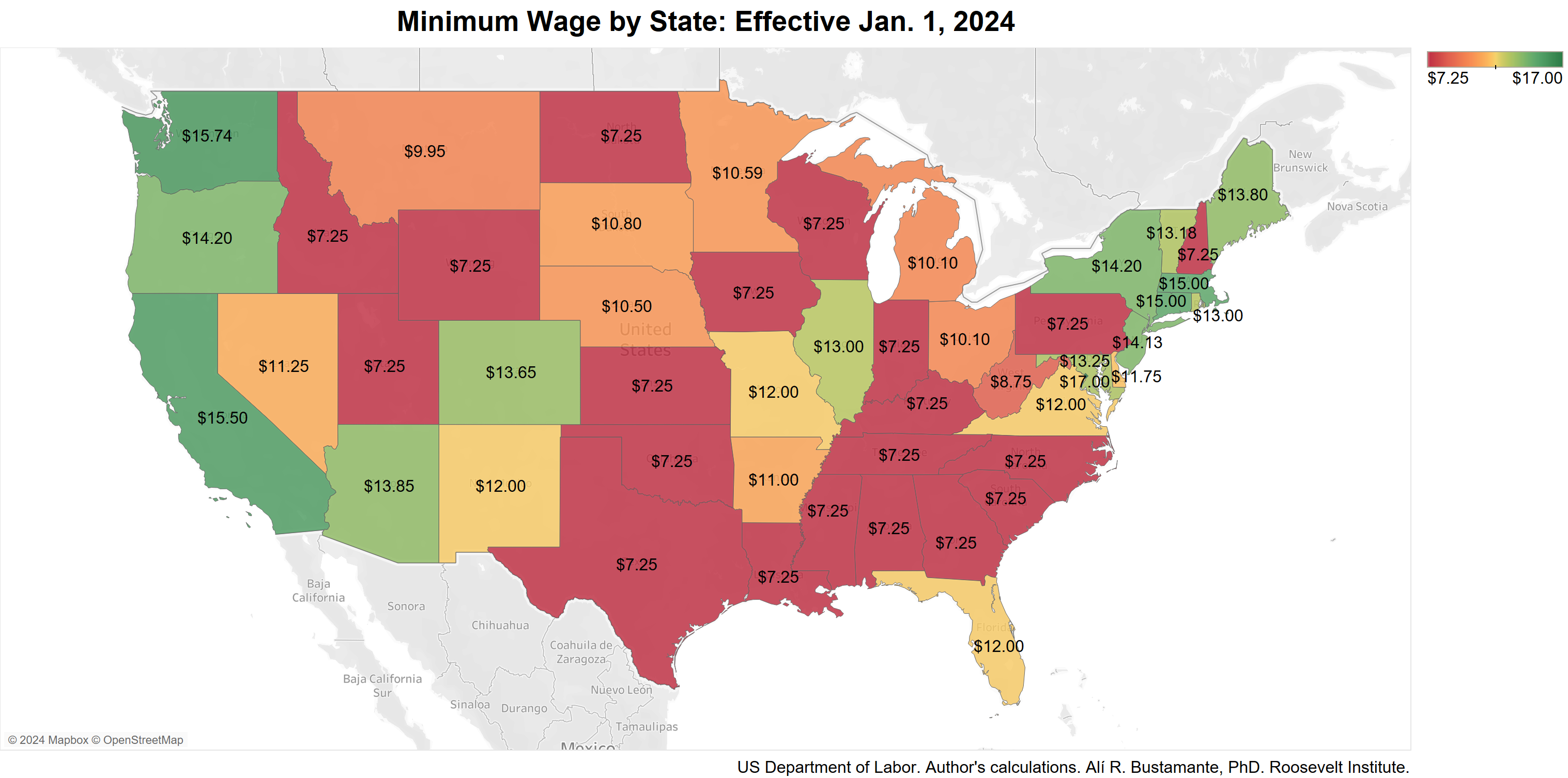

Since 2009, the value of the $7.25 federal minimum wage has eroded by 29.6 percent to $5.10 because of inflation. The majority of the federal minimum wage’s erosion (16.1 percent) occurred prior to the pandemic, but the inflation triggered by pandemic supply shocks—peaking in July 2022—deepened the rate of erosion. Despite the decline in the purchasing power of the federal minimum wage, in 2022, 1 million workers were reported to earn wages at or below the federal minimum—about 1.3 percent of all hourly paid workers (BLS 2023b). The wage floor set by the federal government is salient because 20 states adhere to the federal standard in setting their own minimum wages (figure 1).

Figure 1

Additionally, in the US, the right to form a labor union and collectively bargain over wages and labor conditions is a foundational labor right. Unions have been instrumental in advocating for higher wages and better working conditions (Treasury 2023). However, despite enjoying high levels of public support, union membership has drastically declined from covering about 20.1 percent of workers in 1983 to standing at just 10.1 percent as of 2022 (BLS 2023a). The decline of union density in the US during the past 40 years is the outcome of concerted efforts by American corporations to undermine collective bargaining and resist union formation through the exploitation of weaknesses in labor laws (McNicholas et al. 2023).

This decrease in union representation has been broad in scope. Between 1983 and 2019, the share of workers covered by a union contract declined by more than half in the construction, retail trade, wholesale trade, and transportation and warehousing industries (BLS 2023a). During this same period, union coverage of manufacturing, communication, and mining workers declined by more than 70 percent. This decline has significantly weakened the influence of workers in wage negotiations—contributing to the stagnation of average real wages—and diminished their access to labor protections and job security.

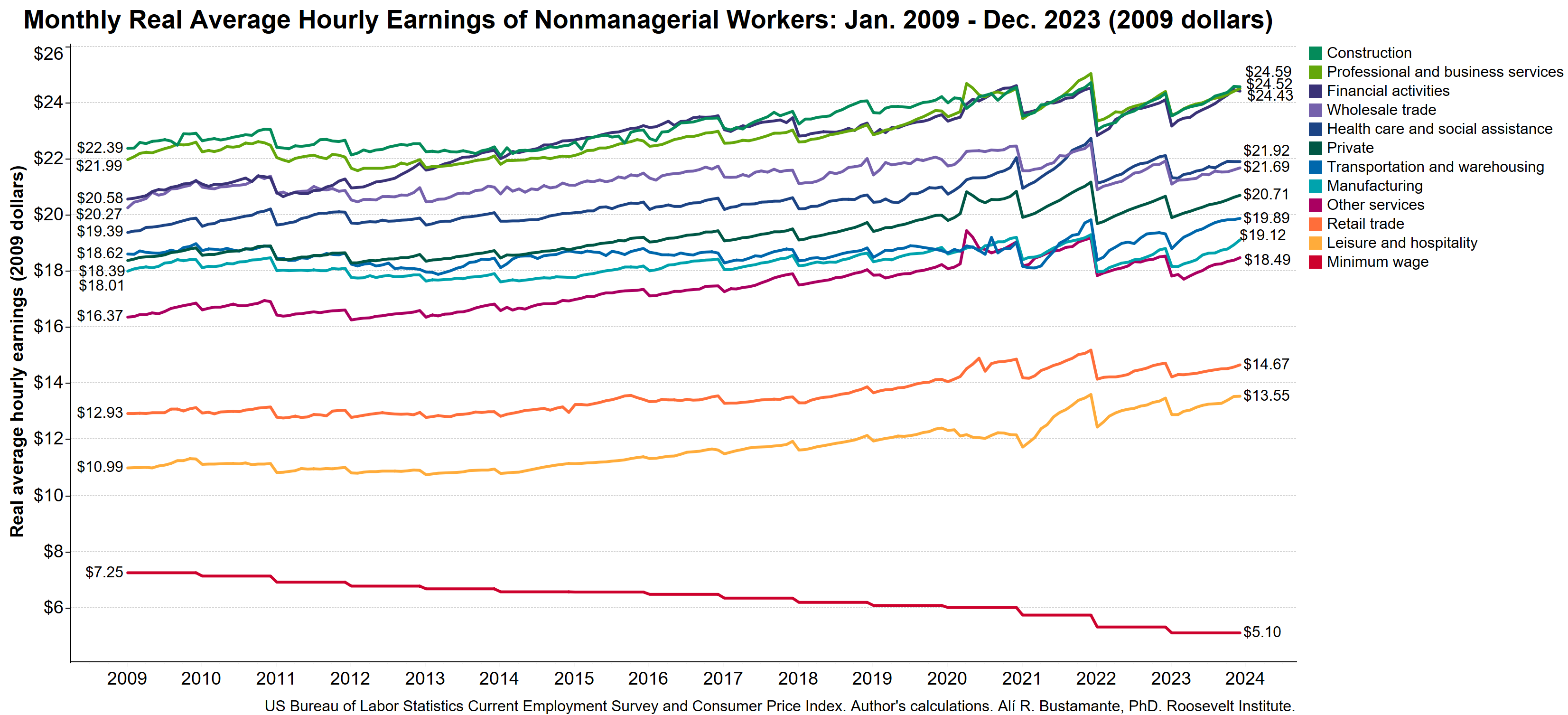

Figure 2

Currently, 57.8 million Americans are employed in five industries where the average hourly wage is below the national average of $20.71 (figure 2). The leisure and hospitality industry employs 16.8 million Americans while retail trade employment is 15.5 million, manufacturing employment is 13 million, and the transportation and warehousing and other services industries collectively employ 12.5 million.

Data show that real wage growth in these lowest-paid industries is generally at or below the private-sector average. Prior to the pandemic, between January 2009 and February 2020, private-sector real wages grew by 8.3 percent, yet wage growth in the manufacturing and transportation and warehousing industries was 3.7 percent and 0.9 percent respectively.