The Deficit-Hawk Takeover: How Austerity Politics Constrained Democratic Policymaking

September 5, 2024

By David Stein

Introduction: Tracing the History of Deficit Politics

In the spring of 1977, soon after being elected, President Jimmy Carter had a difficult encounter with Democratic congressional leadership. He wrote in his diary that “the congressional leadership breakfast was devoted almost entirely to expressions on the part of the liberal members (Tip O’Neill, Shirley Chisholm, and John Brademas) that we were neglecting social programs in order to try to balance the budget in four years.” Carter noted that O’Neill, then Speaker of the House, “flinched visibly whenever we talked about balancing the federal budget or constraining any of the Great Society programs” (Carter 1982, 73).

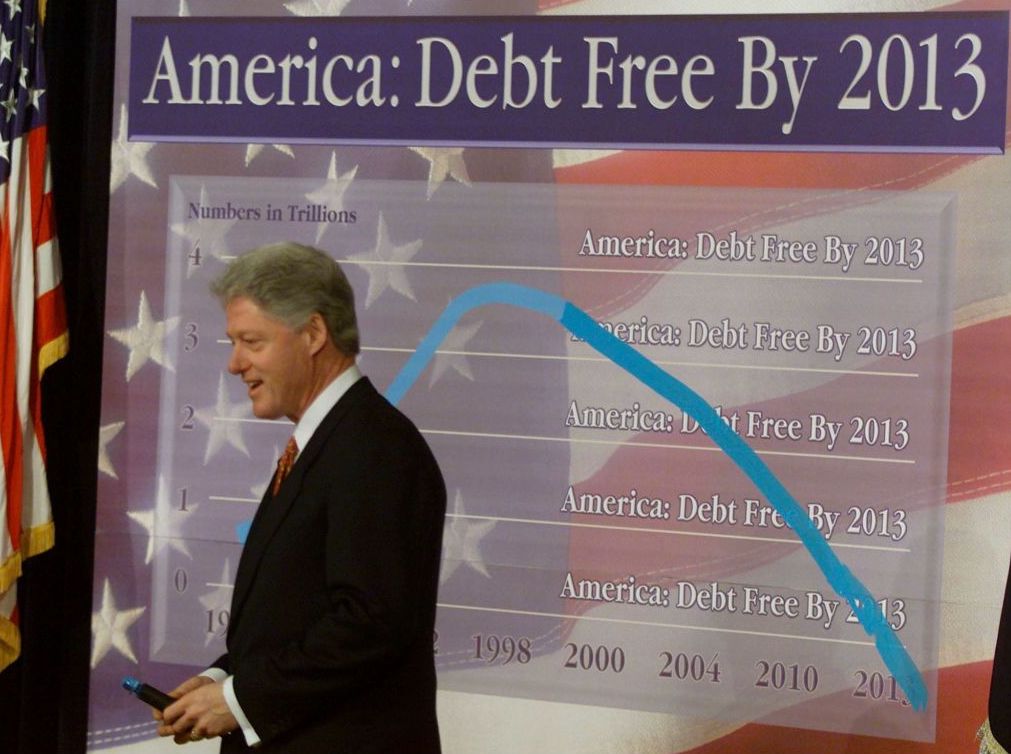

In the 1970s, leaders within the Democratic Party were divided on how to approach public spending and federal deficits. Carter represented a newly prominent wing of the party that was moving away from the Rooseveltian embrace of Keynesianism—utilizing public policy, including government spending, to try to ensure economic stability—and instead favored balanced budgets. While most Democrats still generally believed in some degree of countercyclical policies in a recession, after Carter, they became less willing to utilize deficits to fulfill the goals of economic stability and were more cautious in their countercyclical initiatives. By the end of the century, one side had won this debate about party priorities. In 1993, President Bill Clinton raged sarcastically, “Where are all the Democrats? We’re Eisenhower Republicans here, and we are fighting the Reagan Republicans. We stand for lower deficits and free trade and the bond market. Isn’t that great?” Despite Clinton’s frustration, this new consensus would only solidify over the rest of his time in office. By the 2000s, Democrats across much of the ideological spectrum had firmly embraced the gospel of balanced budgets.

This brief explores how this transformation in approach came about. How did the party most associated with the New Deal, Keynesianism, and countercyclical, fiscal-directed economic management become a party that sought to adhere to balanced-budget fiscal orthodoxy? Why did Democrats embrace a framework that demonized deficits and sought their reduction as a means to lower interest rates and facilitate private sector investment, a fiscal approach that tolerated the organized abandonment of the population to the market and constricted the ambitions of the public sector (Gilmore 2002)?

“The ascent of Democratic deficit hawks ratcheted down the expectations of governments, suggesting that the most important thing policymakers could do is not to provide for the public, but to satisfy private investors.”

In the 1940s, liberals debated various means of direct and indirect government investment, but they took as a given that the private sector was ill-equipped for the task of stabilizing investment across business cycles, and thus stabilizing the production of needed goods and services (Harris 1948, 372). The ascent of Democratic deficit hawks ratcheted down the expectations of governments, suggesting that the most important thing policymakers could do is not to provide for the public, but to satisfy private investors.

Democratic deficit hawks believed shrinking the deficit would encourage the Federal Reserve to lower interest rates, which would catalyze private investment and ultimately create new jobs (Rubin and Weisberg 2004, 355–56). Producing a public good or service ceased to be the key metric of sound economic policymaking. Instead, a policy’s cost-effectiveness or impact on the deficit took precedence. The government’s role was thus mainly to create a climate that pleased private businesses and investors, upon whom, they believed, the social and economic vitality of society overall now rested. As this form of politics became entrenched within the Democratic Party, the deficit hawks constrained social spending proposals at all times, even during recessions.

To be clear, the deficit is important to economic policy, though not in the way that deficit-hawk rhetoric represents it. According to sectoral-balance analysis, developed by British post-Keynesian economist Wynne Godley, a federal government deficit will be offset with a surplus in the nongovernmental sector, and vice versa: A government surplus will be counterbalanced with a nongovernmental or private deficit (Godley 1999). Sectoral-balance analysis emphasizes governmental and nongovernmental sectors as different accounting identities.

Versions of this viewpoint were influential within New Deal–era economic debates. When he was at the Treasury Department in 1934, economist Lauchlin Currie developed a data series called the “Net Contribution of the Federal Government to National Buying Power.” This series would render the net surplus or deficit of government expenditures minus tax receipts to analyze the government’s impact on the economy. If the government took in more tax receipts than it spent—i.e., reducing the budget deficit—it would generally operate as a contractionary force on the economy. And by contrast, if the government received less in taxes than it spent—increasing the deficit—then it would serve to stimulate the economy (Currie 1938). Decades later, economist Alan Sweezy, Currie’s Keynesian compatriot, emphasized the importance of Currie’s innovation: “This was both a technical improvement on the official deficit as a measure of the impact of the government’s fiscal operations on the economy, and even more important a semantic triumph of the first magnitude,” he stressed (Sweezy 1972). Yet, this perspective was never able to become hegemonic in the Roosevelt administration or beyond, as Currie’s boss, Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, adhered to more traditional fiscal conservatism (Zelizer 2000).

Instead, relative intellectual incoherence would become a hallmark of post–New Deal economic policy, with the disjointedness on the issue of public debt a particularly salient feature of this general dynamic (Smith 2020, 59). While most Democratic policymakers after the New Deal generally agreed that some degree of ameliorative countercyclical economic policy was necessary during a recession, there was never firm agreement on the specific role deficits and their composition should play. Additionally, even from a sectoral-balance—or Currie-inflected “net contribution”—perspective, the composition and distribution of specific fiscal policies would shape their impacts.1

In exploring how deficit hawks came to dominate Democratic policymaking between the 1970s and the 2000s—and what was lost as a result—this paper argues that we need a new approach.

In the last four years, we have seen an administration willing to break with a half century of neoliberal orthodoxy in much of its economic policy, but this shift is tentative and piecemeal. Policymakers’ decisions about how to manage deficits in the next few years will be critical to defining a progressive, post-neoliberal approach to economic governance.

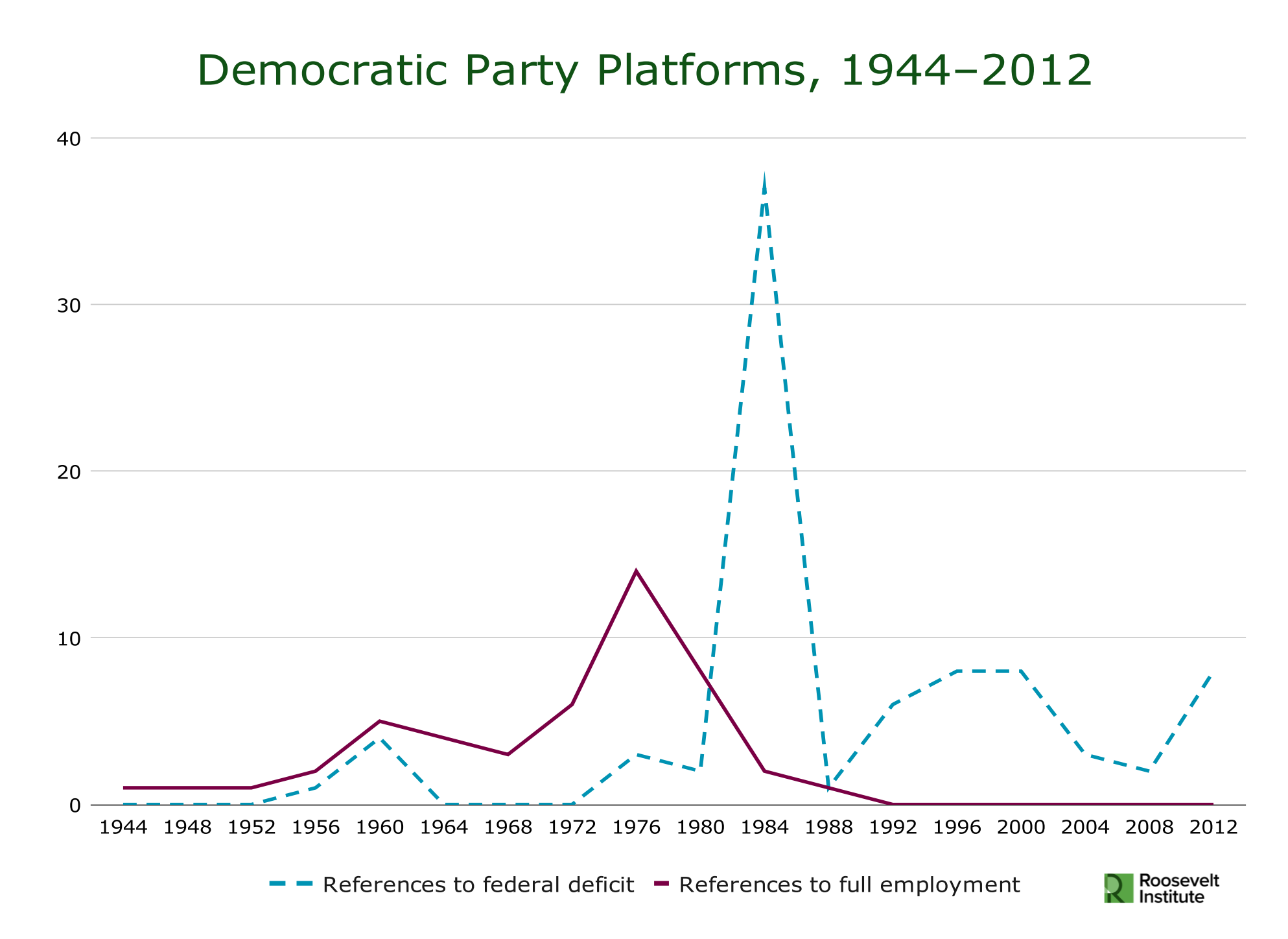

Analysis of Democratic Party Platforms, 1944 – 2012

While the New Deal’s social compact had imagined—if never fully realized—employing deficit spending to ensure economic stability, the commitment to balanced-budget orthodoxy heralded a retreat from these aspirations and techniques. The official platforms of the Democratic Party track this transformation in policy priorities and prevailing ideologies, from the rise of full employment in the 1940s to the dominance of balanced budgets after the 1980s. The 1972 Democratic Party platform, reflecting the power of the full-employment agenda, emphasized that “full employment—a guaranteed job for all—is the primary economic objective of the Democratic Party” (The American Presidency Project 1976). Such a view was echoed again in 1976 and 1980, as it had been in prior decades. But by 1984, full employment barely warranted a mention in the platform—the federal budget deficit, meanwhile, drew 37 references (The American Presidency Project 1984; see Figure 2). That shift in focus would persist during the Clinton years and beyond. This was not just an effort to score political points in election years. At a core level, deficit-hawk politics were about reordering governmental priorities, constraining the ambitions and achievements of the public sector. These policies would eventually undermine efforts to ameliorate the harms of the 2008 recession, and they continue to curtail the prospect for adequately addressing climate change, or making other necessary investments in the care sector that are needed to make the 21st century livable. In short, Democrats need to slough off the shackled imagination of deficit-hawk politics to meaningfully confront the clear challenges ahead.

Figure 2: Author’s analysis of Democratic Party platforms

Key Takeaways

Takeaway #1

From roughly the 1940s to the 2000s, the Democratic party transformed from a party associated with the New Deal, Keynesianism, and countercyclical, fiscal-directed economic management to a party that sought to adhere to balanced-budget fiscal orthodoxy. In the midst of seemingly dry debates over the budget, we cannot lose sight of the real harm anti-deficit policy choices wrought on the nation’s most vulnerable groups, including millions of debt-saddled and downwardly mobile Americans.

Takeaway #2

In the last four years, we have seen an administration that is willing to break with a half-century of neoliberal orthodoxy in much of its fiscal and monetary policy; however, this shift is tentative.

Takeaway #3

Policymakers’ decisions about how to manage deficits in the next few years will be critical to defining a progressive, post-neoliberal approach to economic governance. To fully address the ongoing challenges of climate change and beyond, Democrats will need to eschew the deficit-hawk paradigm.

Footnotes and Suggested Citation

Read the footnotes

1For example, with regard to managing inflation, it is true that fiscal contraction would likely undermine inflation due to the removal of purchasing power from the economy. But much would depend on how this would be done. For instance, one Congressional Budget Office analysis of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) notes that the law’s new regulations on drug pricing will reduce costs to Medicare and Medicaid and result in $237 billion in deficit reduction between 2022–31. This provision would not necessarily have the deleterious impact on purchasing power that other kinds of deficit reduction would have. Similarly, reducing the deficit via stronger Internal Revenue Service enforcement of tax collection from the wealthy would be unlikely to undermine purchasing power in significant ways. Accordingly, the IRA’s discussion of the deficit is an improvement to the Rubinomics-inflected one that reigned from the 1980s to 2020, which held: Reduce the deficit irrespective of inflation. See Higgins 2023.

Suggested Citation

Stein, David. 2024. The Deficit-Hawk Takeover: How Austerity Politics Constrained Democratic Policymaking. Roosevelt Institute, September 5, 2024.