The Role of State Ownership: Overview of State-Owned Entities in the Global Economy

February 12, 2024

By Kyunghoon Kim

"The role of state ownership in advanced countries has also visibly strengthened in recent years. This trend is due to the emergence of two key issues that even countries with more advanced markets struggle to solve without government intervention, namely supply chain insecurity and energy insecurity."

Introduction

This essay reviews state-owned entities’ prominence in the global economy, focusing on the government’s “ownership” in economic entities. Although the government is able to influence corporate activities through incentives, preferences, and regulations, as often discussed in the literature on state capitalism and developmental state, government control over economic entities is particularly strong and direct through ownership. This essay demonstrates that state-owned entities are widespread in various sectors in both advanced and developing countries, and discusses some of the main issues related to state-owned entities in international political economy.

Section 2 of this essay introduces three key types of state-owned entities, namely state enterprises, sovereign wealth funds, and development financial institutions. Section 3 employs data to demonstrate how significant state-owned entities are in diverse sectors and countries. The section first compares the sectors in which state enterprises are present across selected advanced and developing countries. Then, it uses corporate-level data for almost 1,800 state enterprises and analyzes their country and sectoral presence. Next, focusing on the world’s largest companies, the section displays how significant state enterprises are in the corporate landscape. The rest of the section analyzes the sizes of sovereign wealth funds and development banks. Section 4 highlights the background to the reemergence of state-owned entities in various parts of the world and some salient trends.

Three Main Types of State-Owned Entities

The government can be an owner in various forms of entities. The most common types are state enterprises or corporations whose shares are owned by the government. Some of these entities are fully owned by the government, while others are only partially owned. These companies can be further divided into majority state-owned and minority state-owned companies (OECD 2017). Even in a number of minority state-owned companies, the government is the largest shareholder. Countries often have different definitions around ownership, but many generally call companies with over 50 percent state ownership “state enterprises.” State enterprises are often concentrated in industries that produce essential products such as water, electricity, and transportation infrastructure and services. These enterprises are also found in strategic industries such as defense and aerospace. Another area in which state enterprises play a large role is finance. In some developing countries, there continue to be state enterprises in basic industries such as cement and steel, in which market failures linked to positive externalities and coordination failures are perceived to be larger than in advanced countries.

Most state enterprises play a dual role of profit-making and public goods provision, and the balance of the two goals varies significantly across entities and time. State enterprises that focus heavily on profit-making could also contribute to society by paying taxes and dividends to the government.

Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are entities responsible for investing state money (Alhashel 2015). Many SWFs have been created and expanded as the government has injected current account surpluses. These funds are often found in countries with large trade surpluses (i.e., the gap between exports and imports), such as oil producers and China. Some SWFs have been established by receiving fiscal budget or privatization proceeds. Most of these funds have the long-term financial return of state money as their primary goal. Since liquidity is not a key concern for these funds, they make investments with a long-term horizon. To achieve their goal, the funds mix methods of active and passive investment strategy. An active investment strategy involves making targeted investment in diverse asset classes including shares, bonds, derivatives, infrastructure, and property. Passive investment strategy adopts a similar approach to index investment, in which funds have a diversified portfolio that fully or partially reflects the composition of the stock exchange. For commodity exporters, SWFs also play a role in exchange rate stabilization and intergenerational savings and transfers. Some SWFs play a role of financing domestic projects aimed at economic and social development otherwise known as development mandates.

Governments around the world own numerous financial institutions, many of which operate in commercial lending. Governments use public banks as tools to influence credit markets by altering market interest rates and size of loans. They often make the case for state banks on the basis of financial market failures and scarcity of capital. A variety of state-owned financial institutions are referred to as “development financial institutions” or “development banks,” which are primarily driven by public policy objectives or development missions (De Luna-Martinez et al. 2018). The major role of these entities is to provide funding for activities that could have wide economic and societal benefits. As they are assigned this role, these financial institutions have the benefits of having a long-term horizon and higher levels of risk tolerance than commercial banks. Some cover broad sections of the economy, while others cover narrow segments such as small and medium enterprises, cross-border trade and investment, and infrastructure. While maximizing short-term profits is not the ultimate goal, development financial institutions often have a goal of sustaining adequate levels of profitability. Some state commercial banks also have a development mission along with commercial lending, but this essay limits its analytical scope to development banks whose key role is financing development-oriented projects.

Spotting State Ownership

The Reach of State Enterprises in Selected Countries

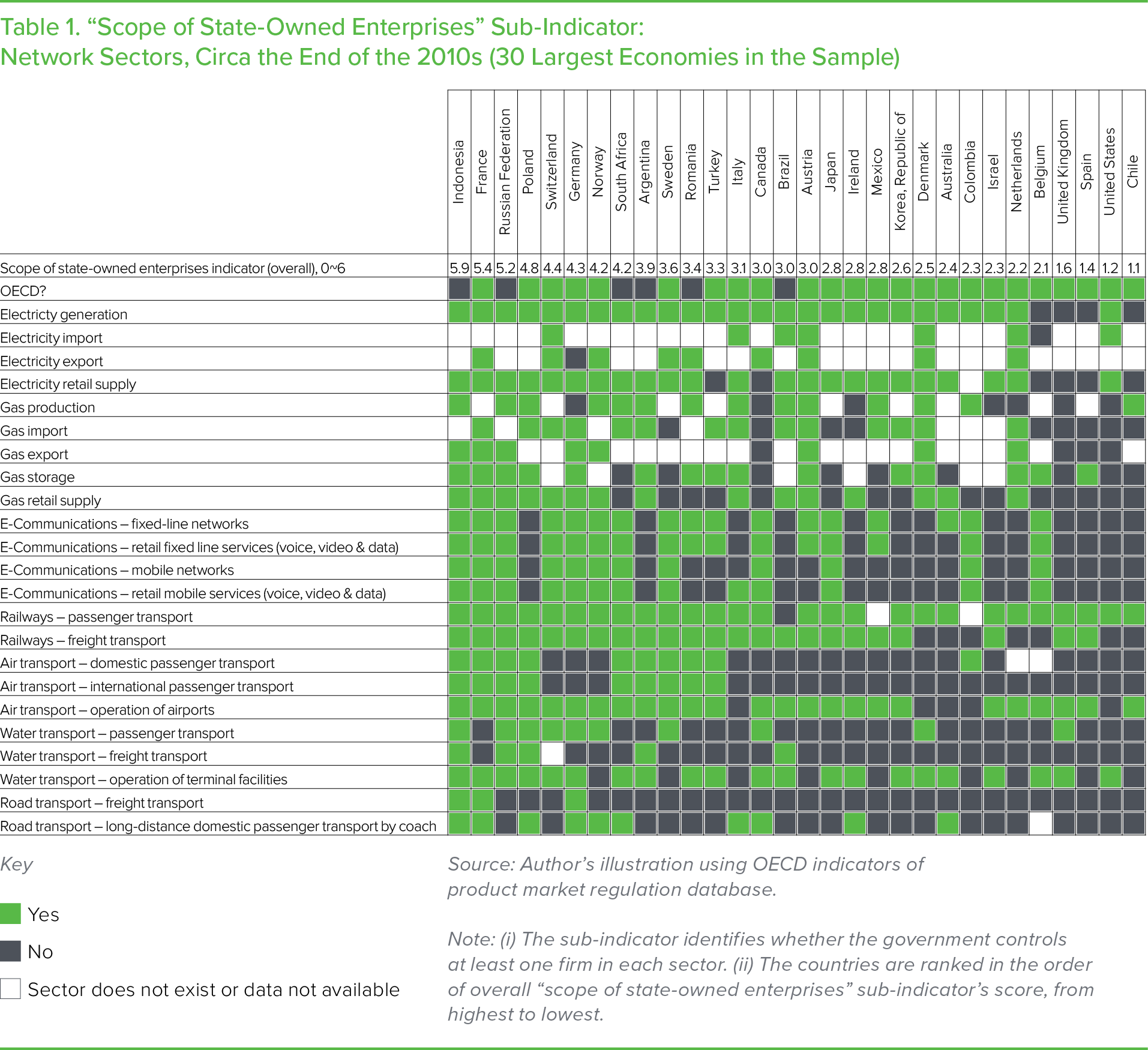

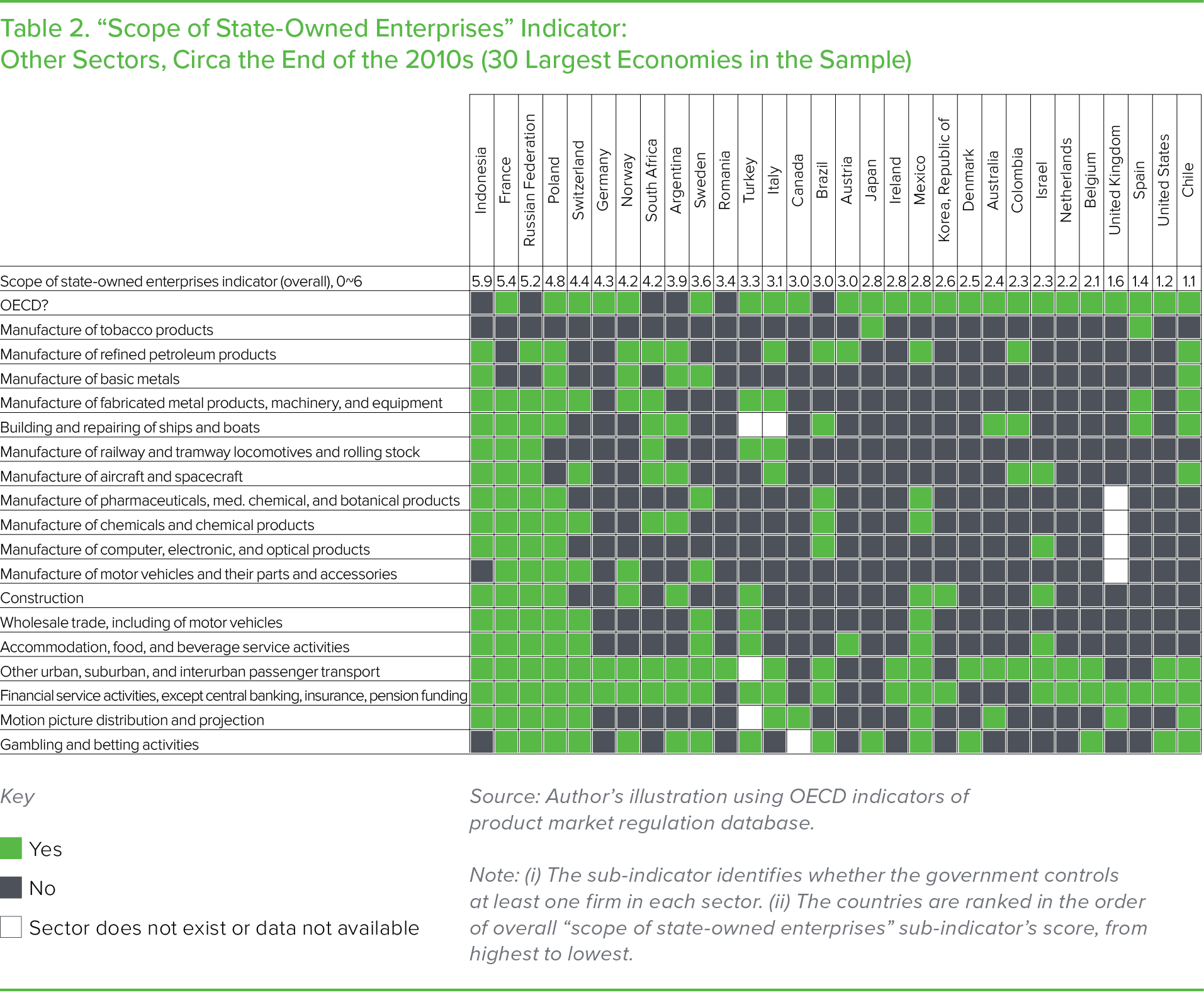

This subsection compares the extent to which state enterprises are present in different economic sectors across countries using a low-level indicator called “scope of state-owned enterprises,” which is a component of the OECD’s “economy-wide product market regulation” indicator (OECD n.d.). This sub-indicator determines whether each country’s government controls at least one company across different economic sectors. The OECD’s dataset provides underlying data for 49 countries—38 OECD countries and 11 non-OECD countries. This subsection focuses on 30 of the largest economies in the dataset—those with GDPs larger than 300 billion USD in 2022. The sample countries are composed of 24 OECD countries and 6 non-OECD countries. Tables 1 and 2 compare the underlying data for the “scope of state-owned enterprises” sub-indicator in network sectors, such as electricity and transportation and “other” sectors that include manufacturing and services. Nearly all economic sectors excluding agriculture are covered.

The overall scores for the “scope of state-owned enterprises” sub-indicator are weighted compositions of variables presented in Tables 1 and 2. For each sector, a score of 6 is given if the government has a controlling firm in the sector and 0 if not, and overall scores are also designed to have the minimum value of 0 and the maximum value of 6. Generally, non-OECD countries, though limited in number and therefore not representative of the group of developing countries, tend to have higher scores than OECD countries. For instance, Indonesia is ranked first with a score of 5.9, followed by Russia (3rd, 5.2), South Africa (8th, 4.2), and Argentina (9th, 3.9). Indonesia’s score is on par with the scores of China (6.0) and Vietnam (5.6), two highly centralized state capitalist economies whose underlying data is not publicly available and therefore not included in Tables 1 and 2. There is significant variation among OECD countries. France is ranked 2nd with a score of 5.4, followed by Poland (4th, 4.8), Switzerland (5th, 4.4), Germany (6th, 4.3), Norway (7th, 4.2), and Sweden (10th, 3.6). At the end of the spectrum are Chile (30th, 1.1), the United States (29th, 1.2), Spain (28th, 1.4), and the United Kingdom (27th, 1.6). Representative northern and western continental European countries are in the former group and representative Anglo-Saxon countries in the latter group (Hall and Soskice 2001).

On average, 10 countries with the highest scores for the “scope of state-owned enterprises” sub-indicator have state enterprises in 27 of 41 sectors. The top three countries have state enterprises in over 30 sectors. Indonesia, the country with the highest score, has state enterprises in virtually all sectors. At the other end of the spectrum, the countries with the smallest numbers of sectors with state enterprises are the United Kingdom (7), Spain (8), and the United States (8).

A quick scan suggests that it is more usual for countries to have state enterprises in network industries than across “other” industries in the OECD database. This pattern is unsurprising considering the public goods nature of the network industries’ products. The average number of countries with state enterprises across different network industries is 14, whereas across “other” industries the number is 10. The number of countries with a state enterprise is particularly high in electricity, railways, and e-communication. Within air transport and water transport, a large number of countries have state enterprises operating airports and seaports. In “other” sectors, more countries have state enterprises in services than in manufacturing. A particularly large number of countries have state enterprises in local passenger transport services and financial services. Within the manufacturing sector, state enterprises in resource-based industries are more common than those in more advanced manufacturing sectors. However, a number of countries have state enterprises in the aircraft and spacecraft manufacturing industry, a sector that is considered strategic for national military capability.

Large State Enterprises’ Country and Sectoral Distribution

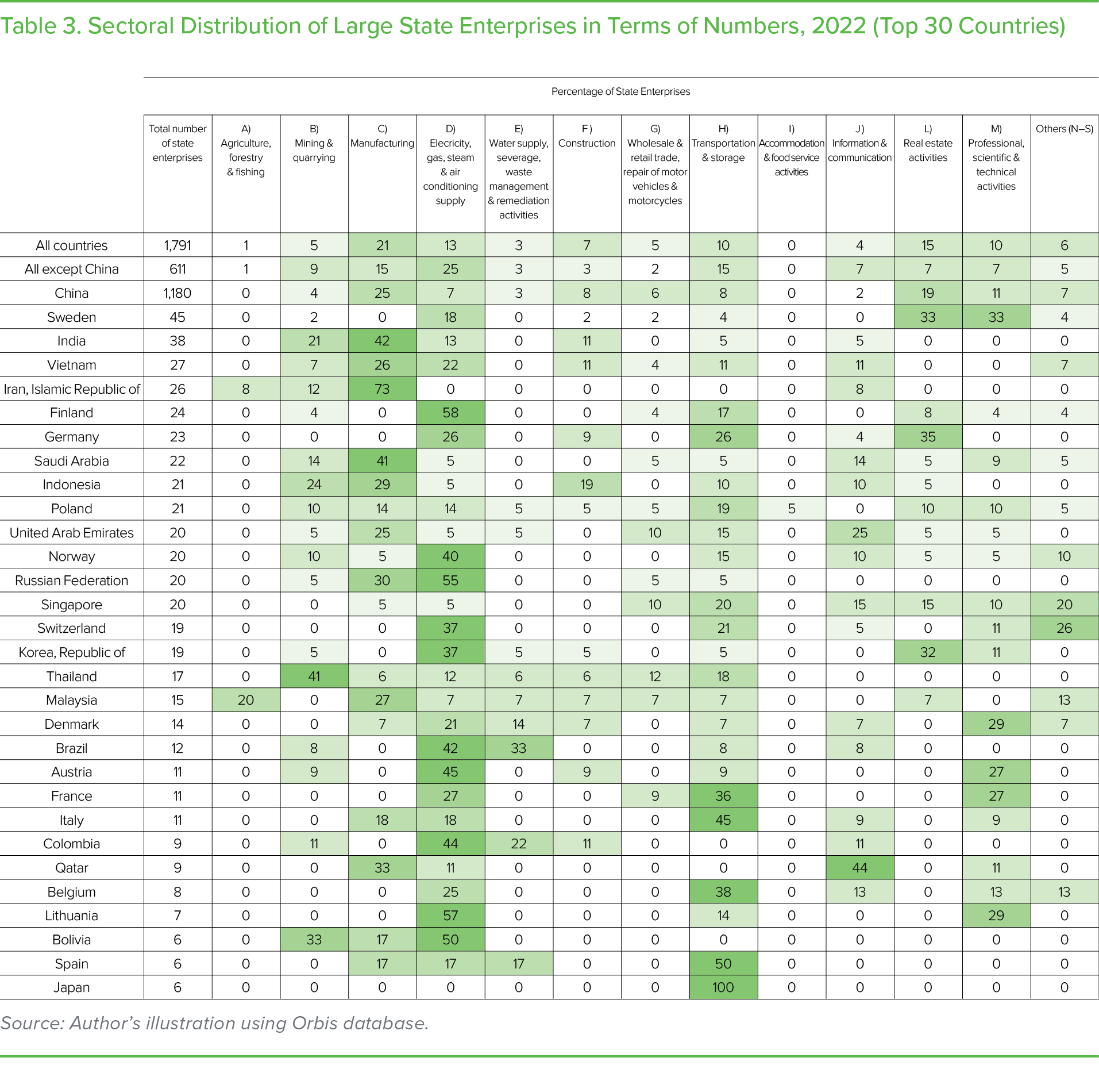

This subsection focuses on a sample of sizable state enterprises. Using the Orbis database, this subsection analyzes the national distribution and characteristics of large state enterprises. The sample includes active companies with the minimum total assets of 500 million USD in 2022 and only includes nonfinancial companies and excludes companies whose primary NACE1 Revision 2 codes are 64, 65, and 66 since financial companies’ assets could obscure the overall picture. For this subsection, state enterprises are companies with an ultimate owner classified as public authorities, states, or governments. An ultimate owner is the final entity in the corporate ownership path, linking the subject company with immediate owners with the minimum control of 50.01 percent. The sample only includes companies with a consolidated statement.

The final list has 1,791 state enterprises. Overall, the sectors with the greatest number of state enterprises are manufacturing; real estate businesses; electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply; and transportation and storage (Table 3). China tops the list with 1,180 state enterprises. China’s state enterprises are concentrated in manufacturing and real estate. Ten countries with the highest score in the first subsection, except for Argentina and South Africa, all have over 10 state enterprises in the sample. Of these countries, Sweden and Germany have a particularly large number of state enterprises: 45 and 23, respectively. For Sweden, the largest state enterprise is the electricity utility company Vattenfall, which is playing a leading role in the energy transition in Northern Europe. Sweden also has numerous real estate companies controlled by governments and their entities. Similarly, the German government has large utility companies, such as Uniper and numerous real estate companies. Indonesia and Norway, which were ranked 1st and 7th in the first subsection, have 21 and 20 state enterprises, respectively. In Indonesia, several state enterprises operate in manufacturing, mining and quarrying, and construction. Norway’s state enterprises are concentrated in utilities. The list also reveals countries with large state enterprises not included in the analysis in the first subsection. After China and Sweden, India has the highest number of state enterprises (38), and Vietnam (27), Iran (26), Finland (24), Saudi Arabia (22), and Poland (21) also have large numbers of state enterprises. Overall, state enterprises are concentrated in manufacturing and utilities in developing countries and utilities, transportation and storage, and real estate in advanced countries.

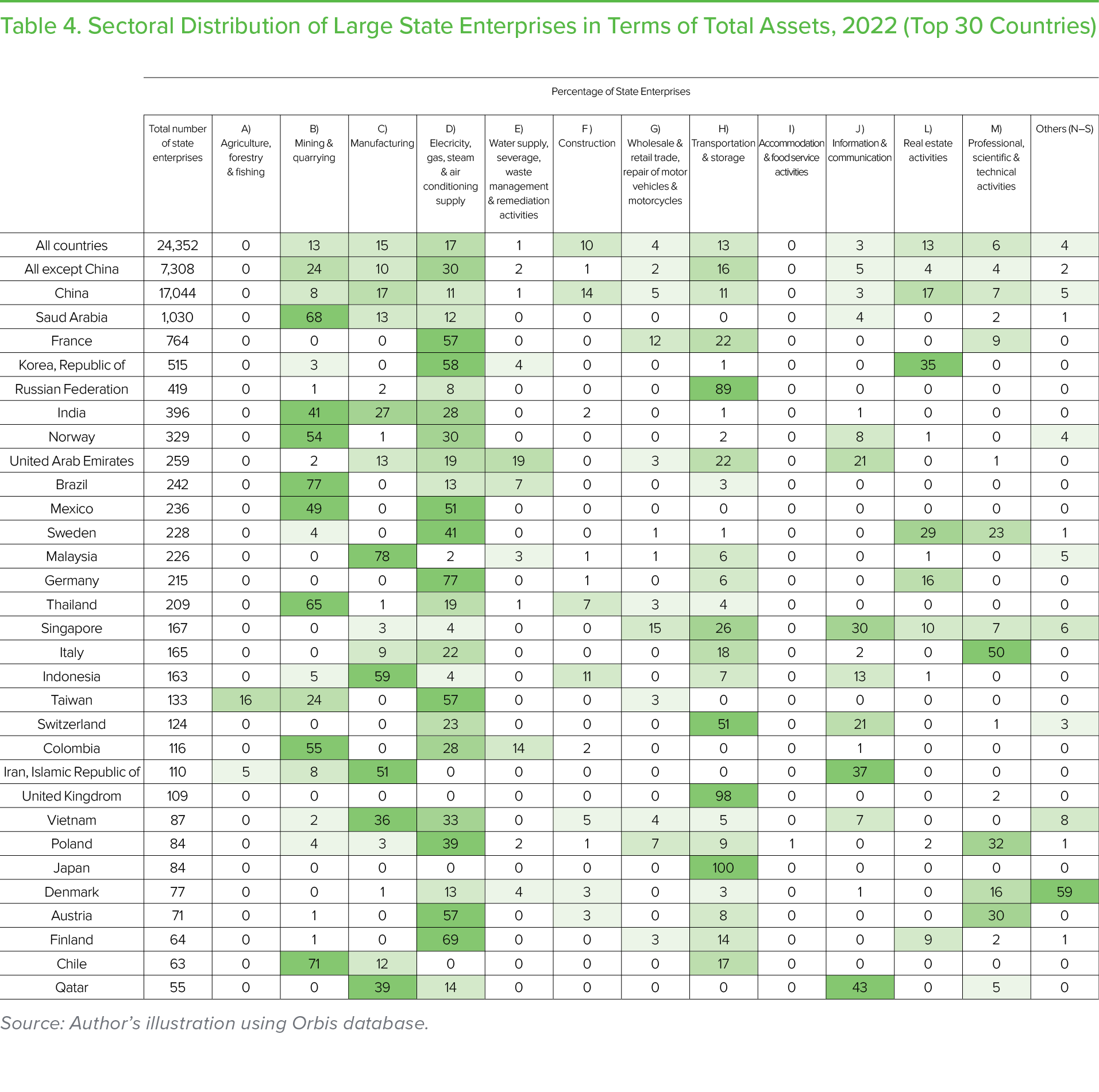

In terms of assets, there are differences in the countries with large state enterprise segments and their sectoral distribution (Table 4).2 China again ranks 1st in terms of state enterprises’ assets. Compared to other countries, the sectoral distribution of state enterprises’ assets is more even in China, with real estate activities, manufacturing, construction, transportation and storage, and electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply each accounting for more than 10 percent of total assets. The rest of the top countries in the list can be divided into two major groups. The first group is large natural resource producers such as Saudi Arabia, India, Norway, Brazil, and Mexico. The share of state enterprises’ assets in mining and quarrying is particularly large in these countries. The second group is advanced countries with large state-owned utilities such as France, Korea, and Sweden. Within public utilities, aggregate assets of state enterprises in electricity, gas, steam, and air conditioning supply are the largest, followed by those in transportation and storage and information and technology.

State Enterprises at the Top of the Corporate World

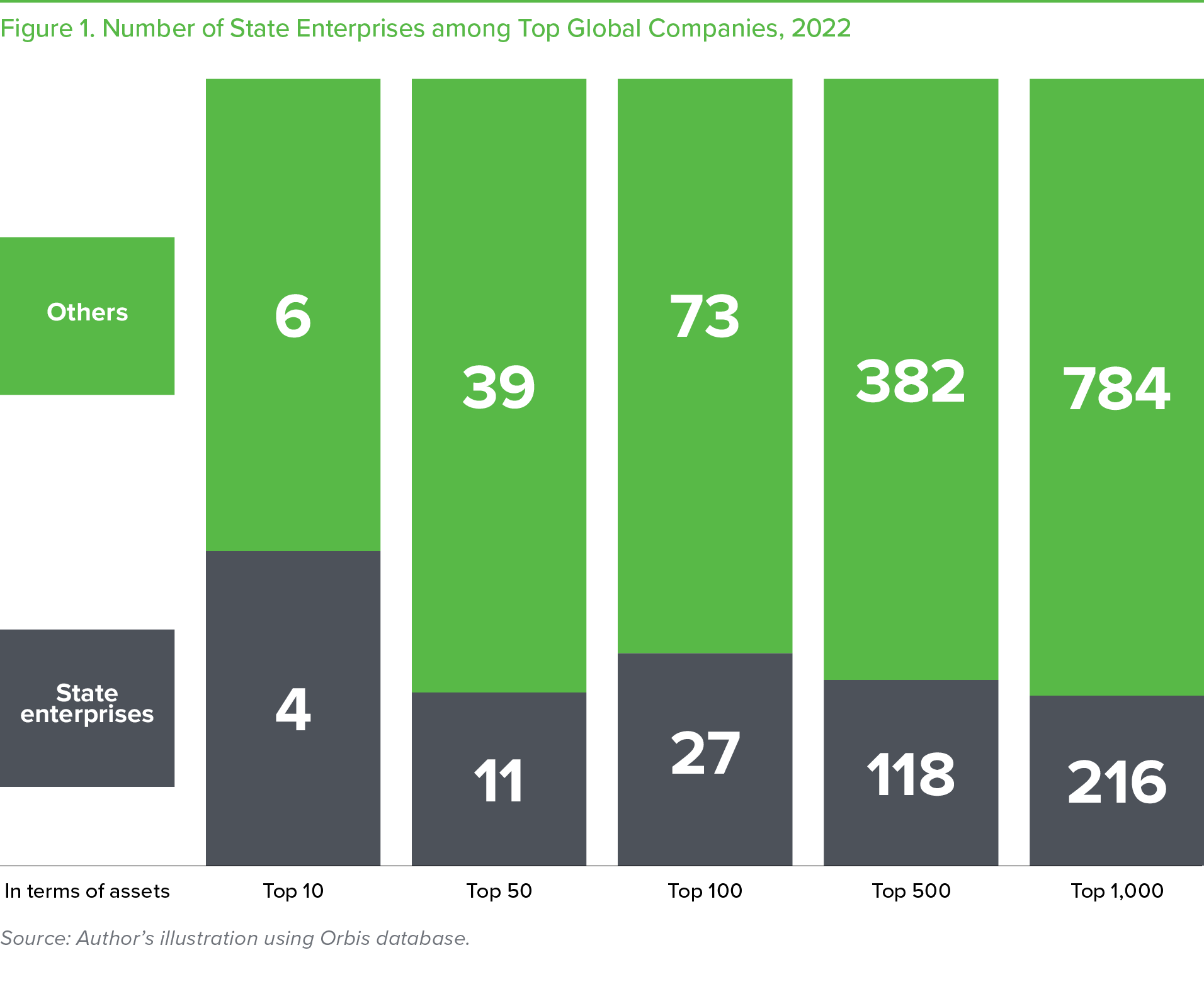

This subsection describes how state enterprises stand out among the world’s largest companies. The subsection uses the same methodology as the previous subsection and modifies the sample to include all companies with or without an ultimate owner and whatever that ultimate owner’s type is. As Figure 1 shows, state enterprises account for over 20 percent of the largest companies in the world, irrespective of sample size. Looking at the 10 largest companies in terms of assets, there are four state enterprises in the group. While many of these state-owned firms are in the countries one might expect (e.g., China), the 7th largest company is Électricité de France (EDF), a state-owned utility company with assets of 413 billion USD.

If one loosens the definition of state enterprises, there is a higher number of companies with state ownership. For instance, Germany’s State of Lower Saxony owns 11.8 percent of Volkswagen, the second largest company in the world. Additionally, an investment arm of Qatar’s sovereign wealth fund owns 10.5 percent of Volkswagen. Deutsche Telekom, the 19th largest company in the world, is 13.8 percent owned by the German federal government and 16.6 percent owned by Germany’s development bank. The Italian government owns 23.6 percent of Enel, the 27th largest firm, and 32.4 percent of Eni, the 73rd largest firm. The Japanese government and public bodies own 32.3 percent of Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation (NTT), the 54th largest company.

Sovereign Wealth Funds

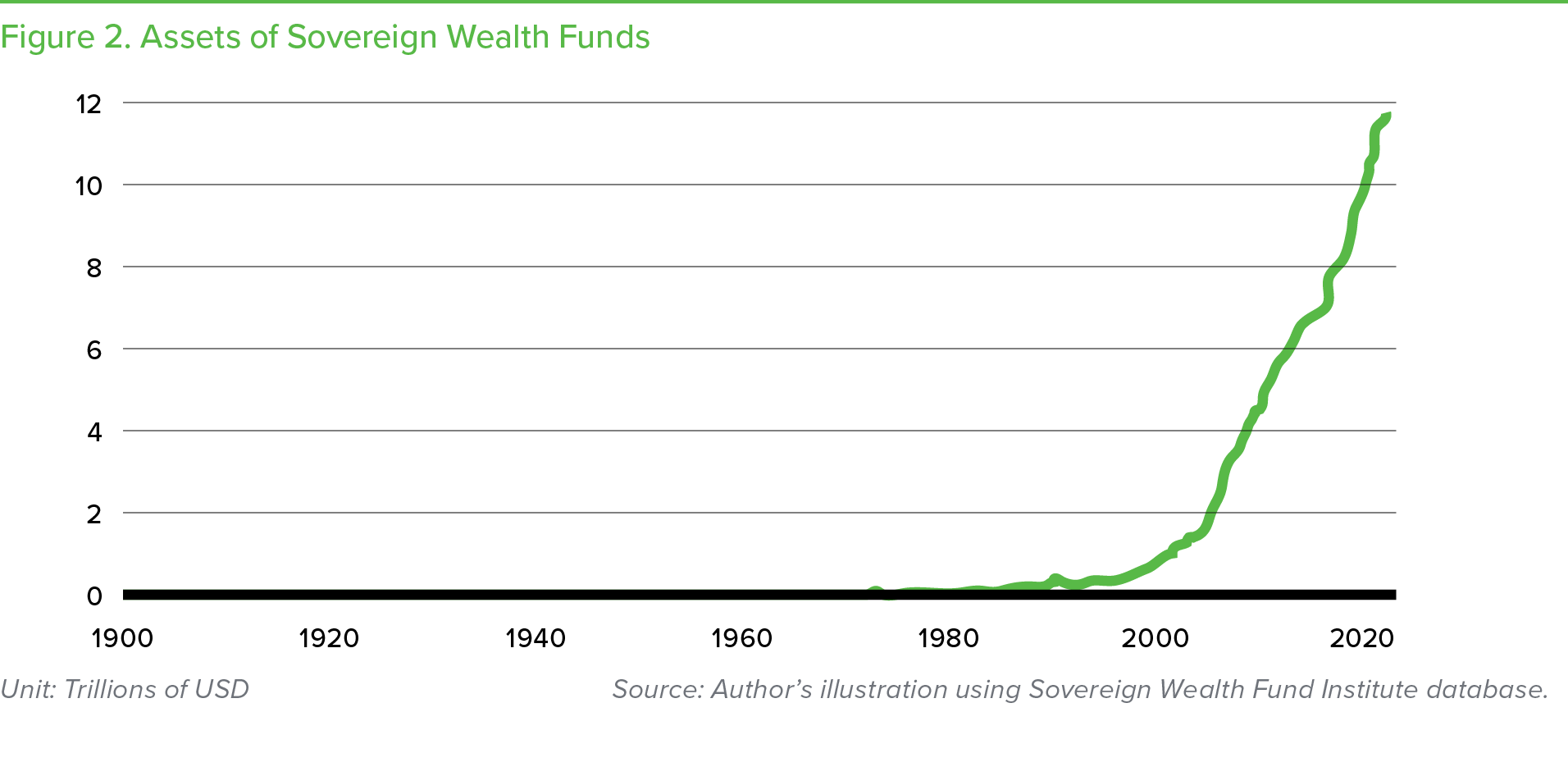

This subsection uses the database of the Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute to analyze the size of sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) around the world (Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute n.d.). SWFs, which are investors of state capital, have grown rapidly during this century. As of 2022, 91 countries together had 163 SWFs, meaning that some countries had more than one SWF. While most countries have one or two SWFs, some countries, notably those with federal political systems, have several subnational SWFs. For example, the United States has 15 SWFs, the United Arab Emirates has 10, Canada has 5, Nigeria has 4, and Australia has 3. SWFs had amassed assets of 11.7 trillion USD by 2022, after having increased by 1 trillion USD on average every two years over the past two decades (Figure 2).

The country with the largest SWF asset is China (excluding Hong Kong).3 China, with three SWFs that have total assets of 2,844 billion USD as of the first half of 2023, is a representative country that is in the group of countries with large current account surplus. As an individual fund, the largest one is Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global, with assets of 1,478 billion USD.

Development Financial Institutions

This subsection analyzes the size, country of origin, and official mandate of development financial institutions (DFIs). The Public Development Banks and Development Financing Institutions database, developed by Peking University’s Institute of New Structural Economics and Agence Française de Développement, is used for this purpose (Xu et al. 2021). The database defines DFIs as stand-alone entities that (i) have a certain level of financial self-sufficiency without repeated budgetary transfers, (ii) deploy financial instruments as their main products, (iii) have a distinct public or development mandate that guides operation, and (iv) have the government as a key entity that controls the institution’s management direction. The sample excludes multinational and subnational institutions and focuses on national DFIs owned by central governments or their entities. For brevity, the term “DFIs” refers to this group.

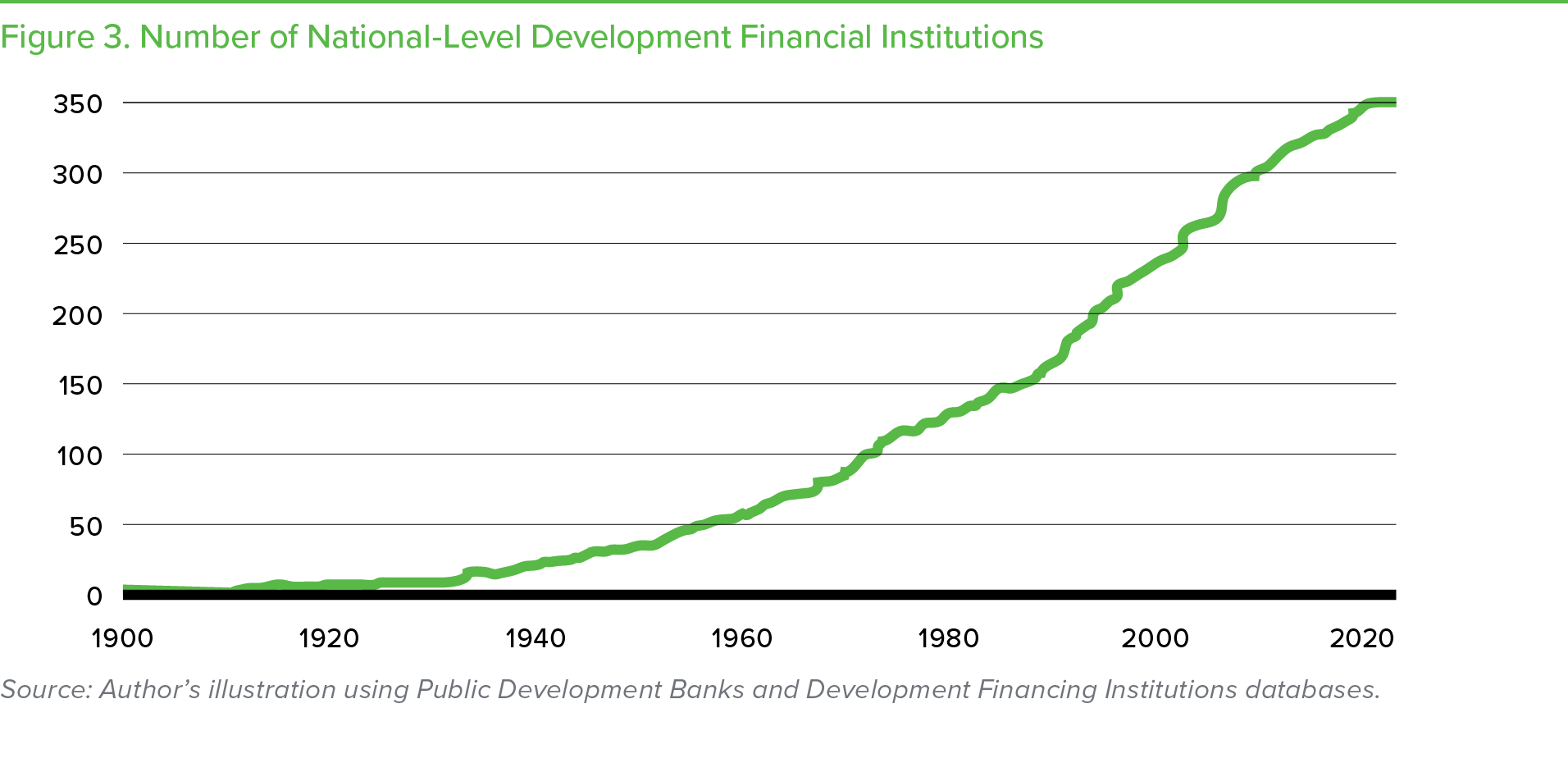

The dataset reveals that 151 countries have DFIs. More than half, or 86 countries, have more than one DFI. As of the end of 2021, there were 351 DFIs, and 5 DFIs were established on average each year over the past two decades (Figure 3). These DFIs’ total assets were 19.2 trillion USD. Two countries, Mexico and Pakistan, have nine institutions, followed by India (eight), Malaysia (seven), France (six), Nigeria (six), and Saudi Arabia (six). China, Japan, Korea, the Netherlands, the Philippines, El Salvador, Thailand, and Zimbabwe each have five DFIs. Approximately a third, or 116 institutions, have broad development mandates, while two-thirds have relatively narrow mandates like supporting small businesses or exporters.

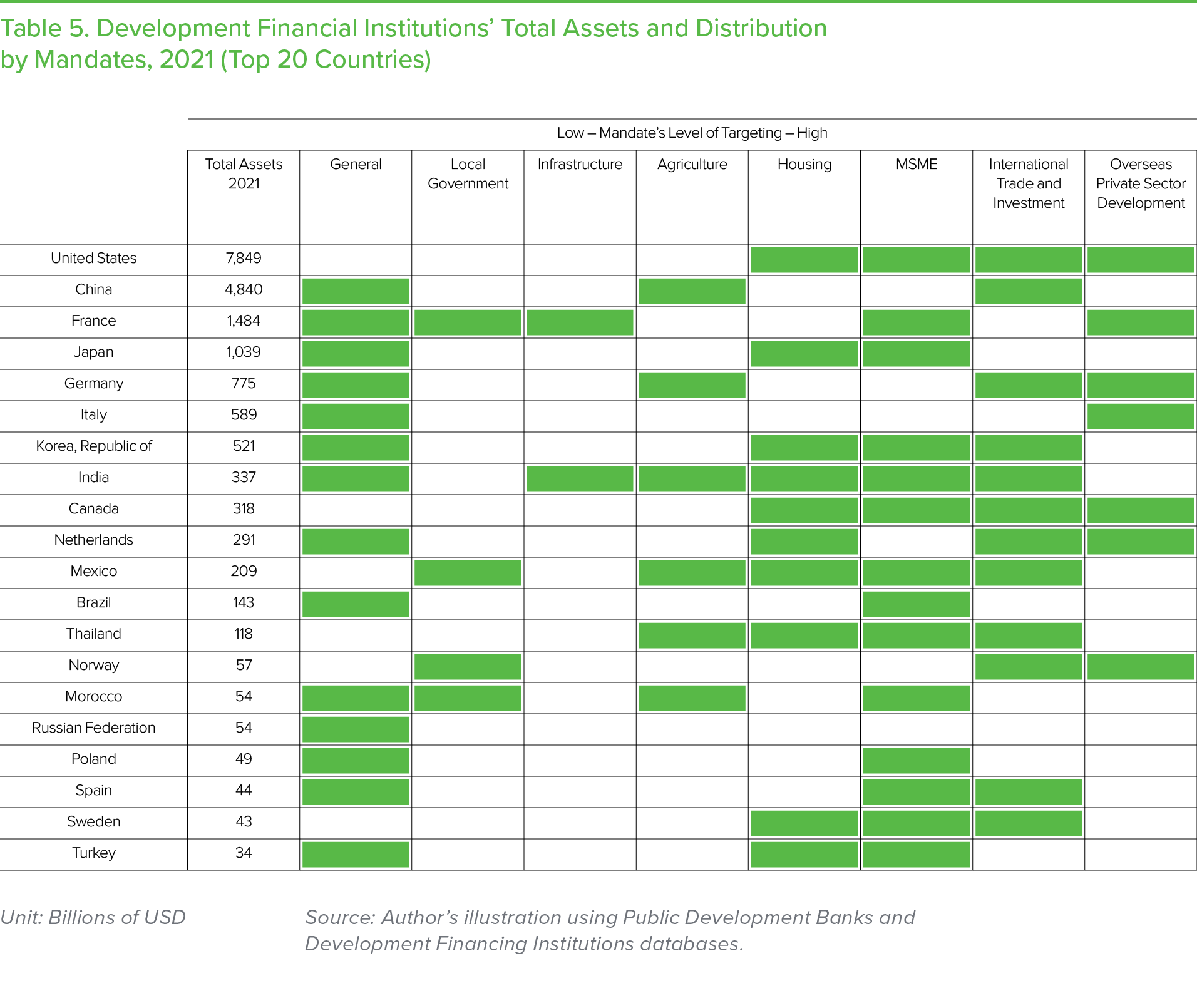

The rank for DFIs’ assets broadly follows that of countries’ economic size. The United States tops the rank with assets of 7,849 billion USD, followed by China (4,840 billion USD), France (1,484 billion USD), Japan (1,039 billion USD), Germany (775 million USD), Italy (589 million USD), Korea (521 million USD), and India (337 million USD). Table 5 shows that most countries have DFIs with general or multi-mandates. Of the top 10 countries in terms of DFIs’ assets, the United States and Canada stand out because they do not have a DFI with broad mandates. These two countries’ DFIs target specific areas such as housing, small enterprises, international trade and investment, and overseas private-sector development. The United States’ major DFIs are Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, which focus on the housing sector. Notably, these enterprises descended from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (1932 to 1957), which did have a broader mandate. Canada’s largest DFI is Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, which focuses on the same sector. On the other hand, France’s DFIs, such as Groupe Caisse des Dépôts (CDC) France, have broader targets. Another large European DFI that has a multi-sector mandate is the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW).

State Ownership and Key Issues

After decades of market-oriented strategy failing to produce sufficient outcomes in sectors with significant market failure, developing countries are looking for solutions by using state-owned entities. One developing country that has made a dramatic turnaround is Indonesia. By the mid-2010s, Indonesia had a weak land transportation system, and this problem was often pointed out as a major obstacle to industrialization (Kim 2023). After the Asian financial crisis, the Indonesian government adopted several rounds of regulatory and institutional reforms with the aim of attracting private investment. But however large the opportunities were in the country with the world’s fourth largest population, private investors have continued to be skeptical as they have perceived high levels of uncertainty. Even as the country experienced economic liberalization, the government has continued to have a large number of state enterprises in diverse sectors, as shown in previous sections, because there was strong nationalistic opposition to full privatization. However, state enterprises have been the target of governance and ownership restructuring, with some of them undergoing partial privatization. During this period, there were weak developmental mandates for state enterprises and their goals shifted toward profit-making while the government limited fiscal support.

When Indonesian President Joko Widodo came into office in 2014, he chose to focus on infrastructure development, working on land transportation with the aim of improving connectivity, which would contribute to industrialization. The government then adopted a systematic program of state-led infrastructure development that involved a variety of state-owned entities. A key reason for mobilizing state-owned entities was that the government is constrained by the fiscal rule that limits annual fiscal deficits to 3 percent of GDP. Given this situation, the government’s viable option has been to leverage state-owned entities. The initial stage of this process was expanding the size of state-owned construction firms such as Waskita Karya, Wijaya Karya, and Pembangunan Perumahan by injecting capital, incentivizing asset revaluation, lowering dividend payout ratios, and assigning a stream of major infrastructure projects (Kim 2021). Another step was to strengthen development financial institutions (Kim 2020). While Indonesia had several gigantic state-owned commercial banks, the government realized that there were risks related to over-relying on them. Therefore, the government significantly expanded a development bank, Sarana Multi Infrastruktur, by injecting capital and using this institution to finance state construction companies’ infrastructure projects. A more recent step of this state-led infrastructure development has been the establishment of a sovereign development fund, called Indonesia Investment Authority, in 2021. The fund’s role is to enable the recycling of infrastructure assets that state construction companies have accrued over the years. By selling these assets to the fund, which has a long-term investment horizon, state-owned construction companies may be afforded the opportunity to conduct new projects. While performance has been impressive across various infrastructure segments, the most notable outcome has been found in the toll road sector. During less than 10 years under the Joko Widodo administration, the government has developed 1,848 kilometers of toll roads. This is more than double the length of toll roads built during the prior four decades (Bhwana 2023).

Furthermore, state ownership is also strengthening in the resource sector as the demand for critical minerals is increasing with the electric vehicle boom. For example, Mexico nationalized its lithium reserves in 2022 and assigned the state enterprise Litio para Mexico to manage the resources (Argen and Stott 2022). Chile is also in the process of nationalizing its lithium industry. In Indonesia, MIND ID, a state-owned mining holding company, nationalized a 51 percent stake of Freeport Indonesia, a major copper producer, in 2018 and a 20 percent stake of Vale Indonesia, a major nickel producer, in 2020. MIND ID is considering a further purchase of shares to become Vale Indonesia’s largest shareholder (Hartati 2023). In 2021, China merged several government-owned rare earth miners into a new giant state-owned entity called China Rare Earth Group in order to strengthen its market dominance and influence in pricing (Yu and Mitchell 2021).

State-owned entities may also be used to allow the government to play a leading role in industrial projects and crowd-in investment and technology for the benefit of the domestic economy.

One case of a state enterprise’s collaboration with private companies is that between the United States’ GE Aerospace and India’s state-owned Hindustan Aeronautics. The two companies signed a memorandum of understanding in June 2023 concerning the joint production of GE Aerospace’s fighter jet engines in India. India is taking advantage of its market power as the fourth largest military spender in the world to attract investment to the defense industry. As part of this strategy, the Indian government is using Hindustan Aeronautics to increase domestic value added and absorb technology from international companies seeking to expand presence in the country. In August 2023, the United States Congressional Notification Process was completed, paving the way for the next step (White House 2023).

The role of state ownership in advanced countries has also visibly strengthened in recent years. This trend is due to the emergence of two key issues that even countries with more advanced markets struggle to solve without government intervention, namely supply chain insecurity and energy insecurity. In June 2023, the Japanese government announced a plan to buy out JSR, a key producer of photoresists, a chemical used in semiconductor production, in an attempt to strengthen the chip supply chain. The state-backed Japanese Investment Corporation plans to acquire the company for approximately 6.4 billion USD in the coming year (Lewis and Inagaki 2023). The Japanese Investment Corporation was established in 2018 with the aim of fostering next-generation industries, and its shareholders are the government (96.5 percent), the Development Bank of Japan (0.4 percent), and leading corporations (3.2 percent). On the other side of the world, even a conservative member of Parliament in Britain proposed acquiring shares in Arm, a key UK-based chip designer, in 2022 as semiconductors became a central issue for economic security (Tugendhat 2022). The UK had already begun to invest in critical assets: The UK government purchased a stake in space company OneWeb by investing 500 million GBP in 2020 (UK Government 2020). Moreover, state capital is becoming even more visible in the defense sector. Twenty-three European governments participated in setting up the NATO Innovation Fund in 2022, which is the “first multi-sovereign venture capital fund” with a firepower of 1 billion EUR that aims to strengthen the defense industry value chain by investing in startups developing emerging and disruptive technologies (NATO 2023).

The resurgence of the role of state-owned entities is also visible in the area of energy security. With goals of achieving stability in energy supply and accelerating carbon reduction, the French government began a process of nationalizing EDF in 2022 to increase its stake from 84 to 100 percent by investing approximately 9.7 billion EUR (Mallet and Thomas 2022). With full ownership, the French government plans to accelerate the construction of new nuclear reactors and transition to cleaner energy. With an increase in energy insecurity due to the Russia-Ukraine war, the German government decided to nationalize a natural gas provider, Uniper, by purchasing a 99 percent stake through the injection of 8 billion EUR in 2022 (Uniper 2022). Furthermore, many government-owned financial institutions are contributing to the energy transition. KfW is playing a pivotal role in leading the coalition government’s plan for the “biggest industrial modernization of Germany in more than 100 years,” in which green industries would play an important role (Chazan 2021). The development bank’s commitment in the area of climate change and environment for the private sector amounted to 19.5 billion EUR in 2022, an increase of 59 percent from the previous year. 10.6 billion EUR were provided in the form of federal funding for efficient buildings, and 7.1 billion EUR under the renewable energies program (KfW 2023). The Norway Government Pension Fund Global, the world’s largest SWF, is nudging its investees to strengthen their contribution to carbon reduction. In September 2023, the fund announced that it would actively demand companies to reach net-zero emissions by 2050 and frequently monitor their progress (Solsvik and Fouche 2023).

Conclusion

This essay has discussed the presence of state-owned entities in diverse sectors across various countries. More recently, with the emergence of polycrisis, a resurgence of active state ownership is becoming more visible. The strengthening of the role of state ownership reflects not only the complexity of economic and societal challenges but also the economic and political thinking that is departing, albeit gradually, from a previous era glorifying market liberalization. Another outcome is the rapid spread of industrial policies, including massive subsidies for strategic sectors across the world, such as in the United States.

Though discussing the possibility of strengthening government ownership in the United States may continue to be taboo, even in the current political landscape in which we may be seeing “one of the largest expansions of government since the 1960s” (Politi 2021) and the “new era of big government” (Brower, Politi, and Chu 2023), state-owned entities must be considered important industrial policy tools. Developing critical technologies, scaling up green industries, and dealing with the weaponization of key commodities requires a stronger role for the government. There may begin to be a change in thinking in the United States as the Biden administration establishes a green bank as a part of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (Lattanzio 2023). Furthermore, if the current speed of subsidy provision to businesses continues for the foreseeable future, there may be questions as to whether government support is worth the money and whether the benefits are appropriately shared with the society (Mazzucato and Rodrik 2023). In situations in which designing, applying, and monitoring conditionalities for the recipients of government subsidies may be challenging, state ownership may offer a solution.

_____

The author would like to thank Todd Tucker for his comments and Claire Greilich, Sonya Gurwitt, and Sunny Malhotra for their editorial contributions.

Footnotes

Read the footnotes

1NACE: Nomenclature statistique des activités économiques dans la Communauté européenne.

2The assets of some of these companies may be double counted as their majority shareholders may be other state enterprises.

3Hong Kong is analyzed separately given its SWFs’ distinct history.

References

Read the references

Alhashel, Badar. 2015. “Sovereign Wealth Funds: A Literature Review.” Journal of Economics and Business 78, (March-April): 1-13. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0148619514000587.

Argen, David, and Michael Stott. 2022. “Mexico Nationalises Lithium in Populist President’s Push to Extend State Control.” Financial Times, April 20, 2022. https://www.ft.com/content/5e579b31-c6f0-4911-899a-e2894240ad85.

Beech, Eric. 2014. “US Government Says It Lost $11.2 Billion on GM Bailout.” Reuters, April 30, 2014. https://jp.reuters.com/article/us-autos-gm-treasury/u-s-government-says-it-lost-11-2-billion-on-gm-bailout-idUKBREA3T0MR20140430/.

Bhwana, Petir Garda. 2023. “Jokowi Claims Citizens Long for More Toll Road Development.” Tempo, July 25, 2023. https://en.tempo.co/read/1751801/jokowi-claims-citizens-long-for-more-toll-road-development#:~:text=TEMPO.CO%2C%20Jakarta%20%2D%20President,he%20built%20over%20the%20years.

Brower, Derek, James Politi, Amanda Chu. 2023. “The New Era of Big Government: Biden Rewrites the Rules of Economic Policy.” Financial Times, June 12, 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/1c6be863-e147-4799-a650-fe3569549295.

Chazan, Guy. 2021. “The Challenge Facing Olaf Scholz’s New Germany Government.” Financial Times, December 7, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/a32b2f0d-5085-4088-b11d-1def2b615413.

De Luna-Martinez, Jose, Carlos Leonardo Vicente, Ashraf Bin Arshad, Radu Tatucum, and Jiyoung Song. 2017. Survey of National Development Banks. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/b029f3b0-0821-5e8c-8438-d9721a720003.

Hall, Peter A., and David Soskice. 2001. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hartati, Euis Rita. 2023. “Government Urged to Acquire Commanding Stake at Vale.” Jakarta Globe, July 12, 2023. https://jakartaglobe.id/business/government-urged-to-acquire-commanding-stake-at-vale.

Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW). 2023. “KfW Chief Executive Officer Stefan Wintels: Transition to a Climate-Friendly, Digital and Resilient Germany has Begun.” Press release, January 31, 2023. https://www.kfw.de/About-KfW/Newsroom/Latest-News/Pressemitteilungen-Details_748352.html.

Kim, Kyunghoon. 2020. “The State as a Patient Capitalist: Growth and Transformation of Indonesia’s Development Financiers.” Pacific Review 33, no. 3-4 (March): 635-668. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09512748.2019.1573266.

______ 2021. “Indonesia’s Restrained State Capitalism: Development and Policy Challenges.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 51, no. 3 (October): 419-446. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00472336.2019.1675084.

______ 2022. “How to Make Indonesia’s Sovereign Wealth Fund Work.” Lowy Institute, July 27, 2022. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/how-make-indonesia-s-sovereign-wealth-fund-work.

______ 2023. “Analysing Indonesia’s Infrastructure Deficits from a Developmentalist Perspective.” Competition and Change 27, no. 1 (September): 115-142. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/10245294211043355.

Lattanzio, Richard K. 2023. EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN12090.

Lewis, Leo, and Kana Inagaki. 2023. “Japan Steps into Chip Supply China with $6.4bn JSR Deal.” Financial Times, June 26, 2023. https://www.ft.com/content/f3451ba6-deea-4d13-a611-c59eef0315a9.

Mallet, Benjamin, and Leigh Thomas. 2022. “France Starts Process to Fully Nationalise Power Group EDF.” Reuters, October 4, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/france-keeps-edf-buyout-offer-12-euros-per-share-filing-2022-10-04/.

Mazzucato, Mariana and Dani Rodrik. 2023. “Industrial Policy with Conditionalities: A Taxonomy and Sample Cases.” Working paper no. 2023/07. London: UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose. https://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/sites/scholar.harvard.edu/files/dani-rodrik/files/conditionality_mazzucato_rodrik_0927202.pdf.

North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). 2023. “NATO Investment Fund Closes on EUR 1 Billion Flagship Fund.” NATO, August 1, 2023. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_217864.htm?selectedLocale=en#:~:text=NATO%20Innovation%20Fund%20closes%20on%20EUR%201bn%20flagship%20fund,-01%20Aug.&text=Twenty%2Dthree%20NATO%20Allies%20have,interest%20to%20join%20the%20NIF.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2017. The Size and Sectoral Distribution of SOEs in OECD and Partner Countries. Paris: OECD. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/deliver/9789264280663-en.pdf?itemId=/content/publication/9789264280663-en&mimeType=pdf.

______ n.d. “Economy-Wide PMR Indicators.” OECD Indicators of Product Market Regulation. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/data/oecd-product-market-regulation-statistics/economy-wide-regulation_data-00593-en#:~:text=Product%20market%20regulation%20(PMR)%20indicators,market%20where%20competition%20is%20viable.

Xu, Jiajun, Régis Marodon, Xinshun Ru, Xiaomeng Ren, and Xinyue Wu. 2021. “What are Public Development Banks and Development Financing Institutions?——Qualification Criteria, Stylized Facts and Development Trends.” China Economic Quarterly International 1, no. 4: 271-294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceqi.2021.10.001.

Politi, James. 2021. “US Tax: Biden Forced into ‘Baby Steps’ on the Road to Fiscal Reform.” Financial Times, October 30, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/5676d5f5-b02f-4064-a9ef-f3bdb7659e19.

Solsvik, Terje, and Gwladys Fouche. 2023. “Norway Wealth Fund Tells Companies to Plan for Climate Transition.” Reuters, September 15, 2023. https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/norway-wealth-fund-tells-companies-plan-climate-transition-2023-09-15/.

Sovereign Wealth Fund Institute. n.d. “Top 100 Largest Fund Rankings by Total Assets.” Accessed January 13, 2024. https://www.swfinstitute.org/fund-rankings.

Tugendhat, Tom. 2022. “The Government Must Stop Arm’s ‘Pass the Parcel’ Treatment and Invest.” Financial Times, May 16, 2022. https://www.ft.com/content/e90cd692-b3a3-4cb8-b9ea-ab47cd99424b.

UK Government. 2020. “UK Government to Acquire Cutting-Edge Satellite Network.” Press release, July 3, 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/uk-government-to-acquire-cutting-edge-satellite-network.

Uniper. 2022. “Agreement on Amended Stabilization Package: Federal Government Acquires 99% Stake in Uniper.” Press release, September 21, 2022. https://www.uniper.energy/system/files/2022-10/20220921-uniper-pr-stabilization-en.pdf.

White House. 2023. “Joint Statement from India and the United States.” Statements and releases, September 8, 2023. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2023/09/08/joint-statement-from-india-and-the-united-states/.

Yu, Sun, and Tom Mitchell. 2021. “China Merges 3 Rare Earth Miners to Strengthen Dominance of Sector.” Financial Times, December 23, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/4dc538e8-c53e-41df-82e3-b70a1c5bae0c.

Explore the Series

Finance as a Tool of Industrial Policy: A Taxonomy of Institutional Options

by Saule T. Omarova

Leading With Industrial Policy: Lessons for Decarbonization from Swedish Green Steel

by Jonas Algers

Just Energy Transition in the Time of Place-Based Industrial Policy: Patch or Pathway to the Green Industrial Transformation?

by Andrea Furnaro

Fair Transition Funds, Employer Neutrality, and Card Checks: How Industrial Policy Could Relaunch Labor Unions in the United States

by César F. Rosado Marzán

Electric Vehicles: How Corporate Guardrails Can Improve Industrial Policy Outcomes

by Lenore Palladino