The Labor Leverage Ratio: A New Measure That Signals a Worker-Driven Recovery

February 4, 2022

By Aaron Sojourner, Emily DiVito

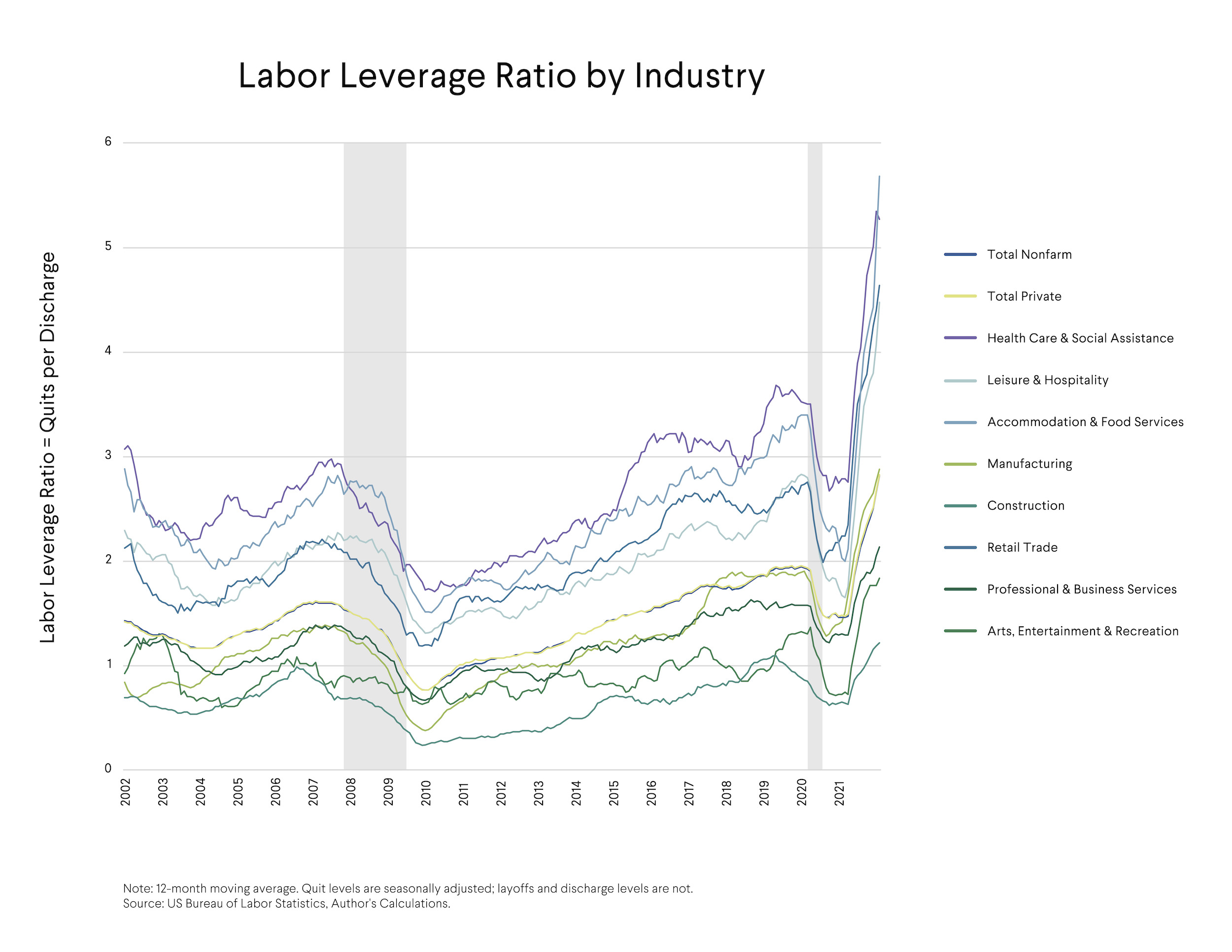

The American labor market is experiencing a Great Upgrade. Workers are quitting jobs at record rates to take better jobs elsewhere, and layoffs are at a record low. To understand what this means for workers, we calculate what Sojourner has coined the Labor Leverage Ratio (LLR): the number of quits initiated by workers compared to discharges, including firings or permanent layoffs initiated by employers.

Good news for both individual workers and the economy as a whole: The LLR is at an all-time high—with about three workers quitting for every one being discharged. After decades of weakening labor bargaining power and eroding labor standards, better jobs and increased worker power are set to drive a more equitable pandemic recovery and prosperity in the years ahead.

Much reporting on the labor market highlights the quit rate, or the rate of employees who choose to voluntarily leave their jobs. But the quit rate alone doesn’t tell the full story. To better account for the power dynamics and other factors that drive job creation and destruction, job quality, and economic growth, we can look to the LLR: the number of employee quits per discharge initiated by employers.

Some of the most common experiences of job termination are when either an employee quits or an employer fires a worker. In either case, the choice is made because the deciding party judges it has better prospects outside of that particular, already-established relationship—for example, when a worker is confident they’ll be able to find a better job elsewhere, or when an employer decides the costs and challenges of replacing an employee are worth it. (While this relationship does not necessarily hold when workers are laid off, layoffs are at an all-time low.)

The current higher LLR is reflective of both a record-high quit rate and a record-low discharge rate. And with quits rising faster than discharges, the increasingly credible possibility that workers will quit is further increasing their bargaining power and lifting the LLR.

A higher LLR does not mean that the economic recovery from the pandemic is complete. Not all workers who have quit or been discharged from their jobs have found better ones elsewhere. Some have dropped out of the labor force entirely, choosing instead to go into early retirement rather than risk in-person work or COVID exposure. Similarly, as the pandemic disrupts care and educational services, some people may leave the labor market to take on additional child, elder, or family caregiving at home. For others, racism in hiring continues to prevent Black and brown workers from full participation in the labor force. The absence of these workers from the labor market is most evident in the employment rate—or the percentage of the total population that is employed—which is still below pre-pandemic levels and recent historic highs. Expanding employment to complete the recovery will require employers to improve job quality enough to attract people off the sidelines.

Still, the current higher LLR breaks from trends in previous recoveries. While during past recoveries, employment prospects were poor and low-wage workers often faced job loss and wage cuts first, the LLR has risen the fastest in low-wage industries—including health care, food services, retail, and leisure and hospitality, all of which disproportionately employ women, workers of color, and workers without a college degree. In other words, workplace leverage appears highest right now for some of the most vulnerable workers, who have also historically faced greater discrimination in the labor market. Wages have been increasing the most in low-wage occupations in many of the industries with the highest LLRs, and not in the sectors with the most inflation. This is a welcome feature of a recovery more equitable than those of the past.

The greater worker bargaining power signaled by a higher LLR is one of the silver linings of an otherwise long, devastating pandemic. COVID upended established workplace norms, raised serious concerns about worker health and safety and employer profitability, and changed the circumstances of many workers’ lives. Employers reacted with big changes to workplace procedures such that many previously satisfied employees find themselves working under conditions they never expected. Individual workers and organized labor responded accordingly, demanding better working conditions and higher pay. And many worker and labor groups are using the pandemic as a catalyst for more aggressive collective action.

Workers have not had such favorable external conditions for organizing in many decades—economic, political, and cultural support are each at a peak. While a rising LLR is a good sign of growing worker power, it’s up to policymakers to make this leverage durable by creating conducive structural conditions. Workers, meanwhile, can cement gains that the current labor market encourages by taking collective action to organize their workplaces and negotiate strong union contracts.

When they do so, the entire macroeconomy benefits. When greater worker power leads to higher wages (especially for low-wage workers), consumption increases, which in turn raises levels of investment and stimulates economic growth—as last year’s unprecedentedly speedy recovery demonstrated.

Though we still have a way to go, the high LLR we see today signals that American workers’ power in the labor market has increased after decades of decline. We need to acknowledge, track, and take advantage of this Great Upgrade.