Citizens United and the Decline of US Democracy: Assessing the Decision’s Impact 15 Years Later

October 2, 2025

By Rachel Funk Fordham

This is a web-friendly preview of the report.

Report Highlights

Introduction

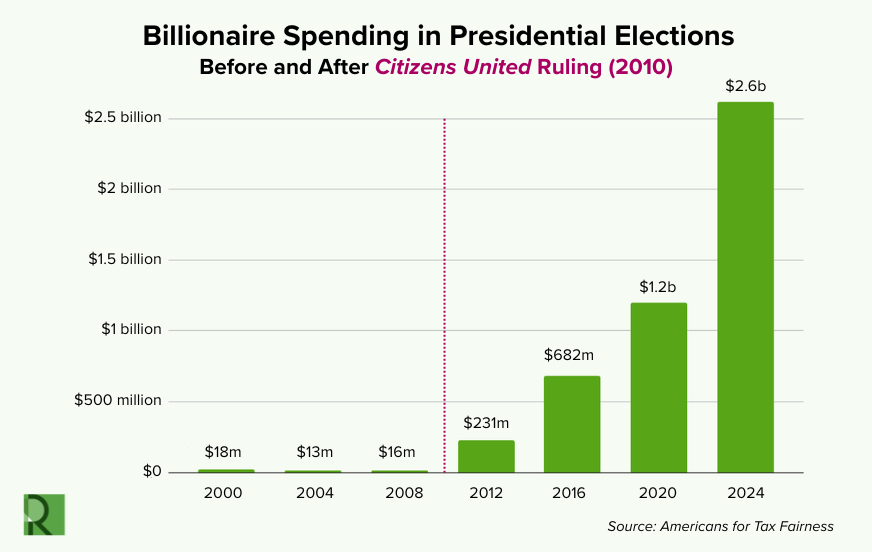

The 2024 federal elections saw the highest level of billionaire spending in American history. In an effort to influence outcomes, billionaire donors and their families spent over $2.6 billion—a figure amounting to nearly 20 percent of total federal election spending that cycle. Nearly three-quarters of billionaires’ spending on the 2024 presidential race supported the reelection of Donald Trump, the country’s first billionaire president (Tashman and Rice 2025). Trump’s opening legislative act in his second term—a massive tax giveaway to the wealthy—earned the dual distinctions of being the most regressive (Badger, Parlapiano, and Sanger-Katz 2025) and the most unpopular (Dale 2025) major law on record.

FIGURE 1

While the 2024 election cycle set new records for billionaire spending, it did so in step with a broader trend. As Figure 1 shows, presidential elections have seen steadily rising spending from the ultra-wealthy for more than a decade. At the same time, the interests of the most affluent citizens and special interest groups have come to dominate policymaking, while the preferences of the average citizen have comparatively little discernable impact on policy outcomes (Gilens and Page 2014).

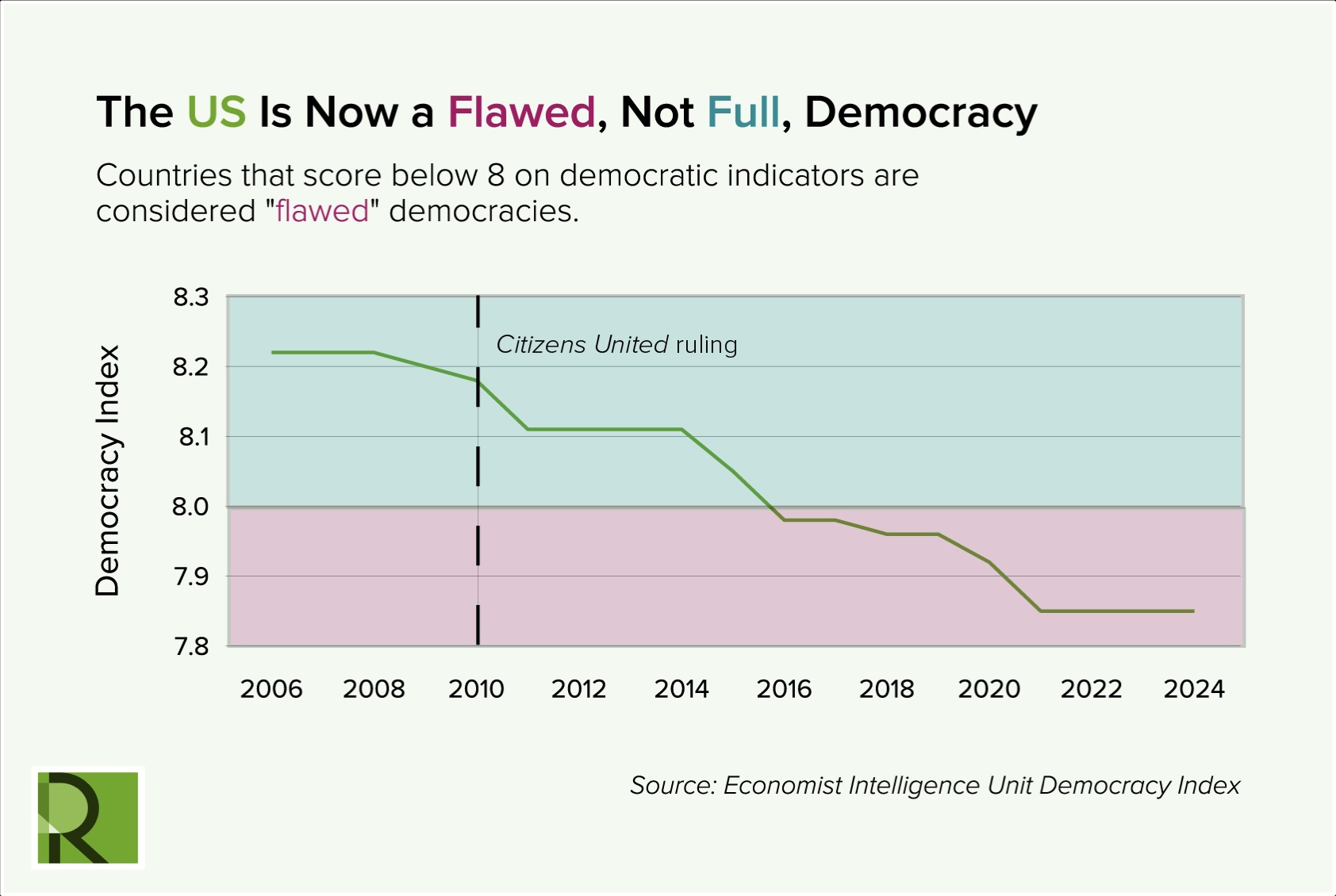

How did billionaires come to wield such outsized influence in our political system? This new era of unprecedented political spending by the ultra-wealthy can be traced back to the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which allowed unlimited money to pour into elections. Over 80 percent of the total amount spent by billionaires during the 2024 election cycle was spent through channels that were prohibited prior to Citizens United,while overall billionaire spending in elections has multiplied by a factor of 163 since the ruling (Tashman and Rice 2025). Meanwhile, over the same period of time, American democracy has been in decline. Public satisfaction with the way democracy is working in the US has reached record lows (Jones 2025), and experts now classify the US as a “flawed” rather than “full” democracy (The Economist 2024).

FIGURE 2

Despite the catastrophic impacts of Citizens United on American democracy, it is deeply entrenched in the political status quo. Presidential candidates from both major parties have gained a competitive edge from unlimited spending (Vogel and Goldmacher 2022). Every current member of Congress has been elected under the post–Citizens United campaign system. And the Supreme Court has signaled that it will continue to expand on the Citizens United rationale (Hurley 2025). While these realities present barriers to reform in the short run, they also heighten the urgency of reviving the campaign finance reform debate. On the 15-year anniversary of the decision, campaign finance reform must once again be placed at the heart of any progressive policy agenda that takes seriously the need for democratic renewal.

Section I of this report provides background on key aspects of the Citizens United decision. Section II revisits some of the central debates about the decision’s potential consequences for democracy that surfaced at the time of the ruling, evaluating them in light of new evidence from the past 15 years. Sections III and IV draw on political science research and examples from post–Citizens United election cycles to show the effects of Citizens United on state and national democratic performance, respectively. Section V puts forward recommendations for shoring up democracy in the post–Citizens United era.

Citizens United Background and Context

On January 21, 2010, the Supreme Court issued a controversial ruling in Citizens United v. FEC that removed restrictions on independent expenditures—a type of political spending that seeks to influence an election without express coordination with a particular candidate, campaign, or political party—by corporations and unions. In the immediate aftermath of the decision, both proponents and opponents of the court’s ruling justified their positions by making arguments about how Citizens United would impact the health of democracy in the United States.

In a concurring opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts claimed that absent the court’s ruling in Citizens United,

“First Amendment rights could be confined to individuals, subverting the vibrant public discourse that is at the foundation of our democracy.”

Justice John Paul Stevens strongly disagreed with this claim in a dissenting opinion, writing that

“the Court’s ruling threatens to undermine the integrity of elected institutions across the Nation . . . At bottom, the Court’s opinion is . . . a rejection of the common sense of the American people, who have recognized a need to prevent corporations from undermining self-government since the founding” (Citizens United v. FEC 2010).

Prominent politicians also spoke out for and against the decision on similar grounds. Then–Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell expressed the view that

“for far too long, some in this country have been deprived of full participation in the political process. [In Citizens United], the Supreme Court took an important step in the direction of restoring the First Amendment rights of these groups . . .” (Good 2010).

On the other hand, President Barack Obama maintained that Citizens United was

“damaging to our democracy . . . Millions of Americans are struggling to get by, and their voices shouldn’t be drowned out by millions of dollars . . . The American people’s voices should be heard” (Lee 2010).

Meanwhile, polling revealed that 80 percent of the public opposed Citizens United, with remarkably little variation across Democrats (85 percent), Republicans (76 percent), and independents (81 percent). A supermajority of nearly two-thirds reported being “strongly opposed” to the decision (Eggen 2010).

The Strategy Behind Citizens United

On its face, Citizens United may have at first seemed like a case that was unlikely to make waves in the legal, political, or public spheres. The plaintiff, nonprofit organization Citizens United, sought to challenge Section 203 of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA) because the provision prevented it from drawing on corporate funds to promote and broadcast a documentary critical of presidential candidate Hillary Clinton ahead of the 2008 primaries. Based on prior Supreme Court precedent, a federal district court initially issued a straightforward ruling against Citizens United that upheld the BCRA restriction barring corporations from funding electioneering communications.

Yet under the surface, Citizens United was part of a yearslong coordinated effort to chip away at existing campaign finance regulations through strategic litigation. Seeking to take advantage of a recent compositional change to the Supreme Court that shifted the pivotal justice in a direction more favorable to deregulation, Citizens United purposefully violated provisions of the BCRA with its documentary Hillary: The Movie and hired experienced litigators with a track record of trying similar cases in front of the Supreme Court.

This strategy paid off. When Citizens United appealed the district court ruling, a sympathetic Supreme Court used its discretionary powers to grant certiorari and agree to hear the case. Following the first oral arguments, the court invited briefs on broader questions of reversing judicial precedent, rather than ruling on the more narrow question of whether Citizens United could distribute its documentary film. Finally, on January 21, 2010, a slim 5-4 majority issued a sweeping ruling in favor of Citizens United, finding that any restrictions on corporate independent expenditures violated the First Amendment. While some doubted whether Citizens United would have much of an impact, seeing it as a relatively minor change to the campaign finance regulatory landscape (Bai 2012), the lawyer who first introduced the case considered the effort to be “awfully successful” (Kirkpatrick 2010).

The Legacy of Citizens United

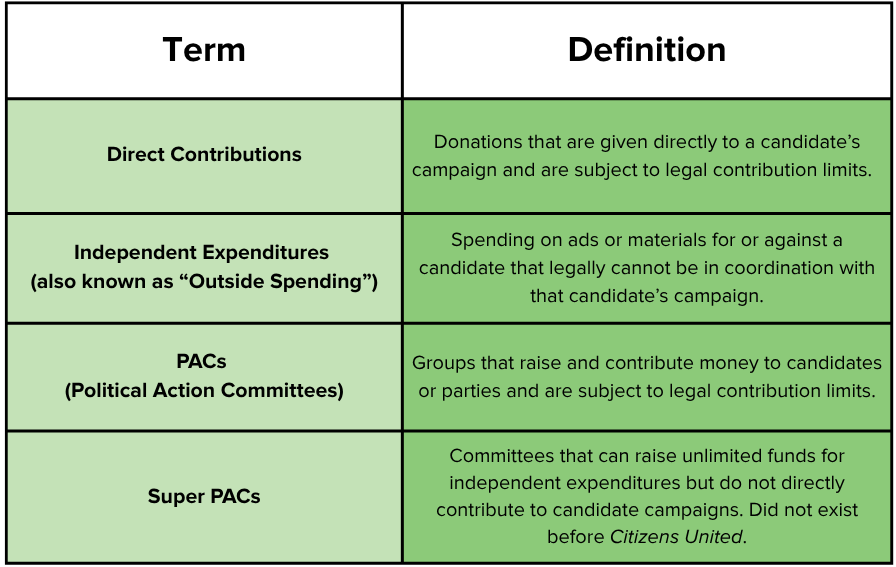

The full impact of Citizens United was not felt at once. The most direct and immediate consequence of the ruling was the nullification of federal and state-level bans on independent expenditures by corporations and unions, but it also had more indirect and far-reaching effects. The legal rationale set forth in the Citizens United majority opinion both preempted future federal and state campaign finance regulation and opened the door for new avenues of political spending. By redefining corruption to include only clear quid pro quo exchanges and recasting campaign finance as a First Amendment issue, Citizens United sent a strong signal that any legislative attempt to limit spending in elections would face formidable legal challenges. In addition, the legal reasoning from Citizens United was directly applied by a federal appellate court in SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission (2010) to eliminate all limits on donations to independent expenditure–only groups, leading to the creation of super PACs.

Super PACs are political action committees that only make independent expenditures. As such, they may raise and spend unlimited sums from any source, but they are prohibited from making contributions to or coordinating with political candidates. On paper, they are required to periodically report their donors to the Federal Election Commission (FEC). In practice, however, donors to super PACs can avoid transparency by strategically timing their contributions around reporting deadlines or funneling money through an intermediary organization that is either not subject to disclosure requirements or has complex financial records that make the original sources of money difficult to track. Common types of intermediary organizations are 501(c)(4) and 501(c)(6) nonprofit organizations, also sometimes referred to as “dark money” groups, which are permitted to engage in partisan electoral activity without disclosing their donors. These organizations are also able to accept unlimited contributions and can make their own independent expenditures (without contributing to a super PAC).

Table I. Campaign Finance Terms and Definitions

For simplicity, this report refers to the type of political spending allowed by Citizens United as “independent expenditures” or “outside spending.” These terms are used interchangeably and refer to unlimited political spending that (1) can be disclosed or undisclosed and (2) lacks formal ties to any candidate, campaign, or political party. When relevant, distinctions are drawn between disclosed and undisclosed expenditures, but in practice disclosure is nearly always imperfect.

Large-Scale Reforms

1. Constitutional Amendment or Reversal of Citizens United

The two methods of overturning Citizens United are a constitutional amendment or a new Supreme Court ruling to reverse the precedent set by Citizens United. Draft constitutional amendments usually focus narrowly on the court’s decision itself, eliminating any constitutional basis for extending First Amendment rights to corporations. While this opens the door for legislative action to limit independent expenditures, it does not do enough on its own to reverse the negative effects of Citizens United. A more effective constitutional amendment would include language that directly limits the amount and type of spending in elections. Similarly, an effective legal challenge to Citizens United would need to go further than reversing the court’s ruling on corporate independent expenditures. It would also need to produce a new evidence-based, pro-democracy legal rationale that addresses both the direct and indirect effects of the prior precedent.

2. Legislative Reforms

Short of overturning Citizens United, legislative reforms could bolster enforcement of current campaign finance laws or strengthen disclosure requirements. Current regulations requiring some disclosure and prohibiting coordination between outside spending groups and campaigns are frequently violated and poorly enforced. Better enforcement would be an improvement over the status quo, but it would not address the antidemocratic consequences of outside spending, which mostly stem from legal forms of spending. More complete disclosure requirements are a partial solution. While this approach would not address the unlimited nature of independent expenditures, robust disclosure may reduce spending that deceives voters or supports political causes that would engender public backlash. The ideal reform would require timely disclosure of the original source of donations to any outside-spending group and make that information accessible to voters. Short of comprehensive disclosure, the second-best reform would require outside-spending groups that do not disclose their donors to reveal that fact in every communication to voters.

3. Public Financing for All Campaigns

The third option is to provide public funding for all campaigns. Public funding is now available in a small subset of elections in the form of grants, small-donor matching programs, or vouchers that voters can then allocate to campaigns. This class of reforms is the most promising, because it addresses nearly all of the democratic distortions caused by Citizens United. Public financing is transparent, limited, and equalizing. It is a powerful, pro-democratic alternative to the current system of unlimited independent expenditures. However, public financing is less likely to be successful if implemented within the existing campaign finance system that allows for unlimited outside spending, because it cannot compete with unlimited sums from outside sources. The best campaign finance policy solution to address the democratic harms caused by Citizens United would be to reverse Citizens United and roll out a nationwide system of full public financing for all political campaigns.

A long-term strategy to undo the damage to democracy caused by Citizens United should include efforts to build momentum for major national campaign finance reforms. These efforts may include supporting pro-reform candidates, applying sustained public pressure, and building the evidence base showing the negative effects of Citizens United as well as the positive effects of smaller-scale reforms that have been adopted by states and localities. The case for reform should center straightforward pro-democracy arguments rather than partisan considerations or complex legal reasoning.

In the meantime, two strategies can more immediately address the negative consequences of Citizens United on democracy.

Immediate Reforms

1. New Incentive Structures for Candidates and Parties

The first strategy is to redefine the incentive structure for candidates and parties by making reliance on outside spending an electoral liability. Two recent elections, the 2025 Wisconsin Supreme Court election and the 2025 New York City Democratic mayoral primary election, show how this strategy can be successfully executed. Both elections broke outside spending records. The state supreme court election in Wisconsin attracted around $57 million in outside spending (Brennan Center for Justice 2025), while the New York City mayoral primary drew $28 million in independent expenditures (Smith 2025). On paper, both nonpartisan judicial elections and mayoral primaries are exactly the type of low-salience elections in which outside spending should have the most influence. However, in both elections, the candidate with an outside-spending and overall-spending disadvantage won. These races were unique in many ways, but they had two things in common. First, both winning candidates made outside spending an issue in their campaign, criticizing their opponent for relying so heavily on independent expenditures from billionaires (Burness 2025; Fandos 2025). Second, there was sustained media attention on the amount and sources of independent expenditures in both races.

Experimental studies also show that voters are less likely to support candidates when reliance on outside spending is revealed. Candidate favorability drops significantly when voters are informed that the candidate received support from super PACs or groups that do not disclose their donors (Goodliffe and Townsend 2024; Rhodes et al. 2019). Voters across the political spectrum punish candidates for receiving support in the form of undisclosed independent expenditures, even when the candidate is aligned with them on policy (Wood 2023).

The strongest form of this strategy would involve candidates or party organizations voluntarily eschewing outside spending, forcing their opponents to either do the same or justify their dependence on wealthy donors to voters. At the beginning of his first presidential run, Donald Trump rose to the top of a crowded primary by initially rejecting outside spending (Levinthal 2016). This year, eight sitting Democratic senators called for their party to ban super PACs in Democratic primaries (Reston 2025). However, in whatever form it takes, this strategy depends on candidates, journalists, and pro-democracy organizations drawing sustained attention to the role of outside spending in elections.

2. Coalitional Politics

The second strategy is to build a coalition that jointly prioritizes policies promoting economic equality and political equality. Citizens United created new avenues through which economic power can be converted into political power. Mitigating its negative effects on democracy requires addressing both economic and political inequality. These are mutually reinforcing goals and should be pursued together. For example, a wealth tax would reduce the outsized influence of top donors on election and policy outcomes, while guaranteeing voting rights and banning gerrymandering would give those at the other end of the wealth distribution more of a say. Strengthening unions and workers’ ability to organize reduces wealth inequality (Tippet, Onaran, and Wildauer 2024) and improves legislative responsiveness (Becher and Stegmueller 2021). Investing in social programs addresses poverty and promotes political participation (Michener 2018). And there are many other economic, social, regulatory, and institutional reforms that would fit into a pro-democracy agenda that centers equality.

The Citizens United ruling enabled concentrated economic power to bend politics to its will, amplifying the preferences of a small, ultra-wealthy minority at the expense of the vast majority of the American people. The decision was part of a coordinated effort to shift the balance of power in the US toward the wealthy. It will take an equally coordinated effort to create a more equitable balance of power and protect democracy going forward.

Suggested Citation

Fordham, Rachel Funk. 2025. Citizens United and the Decline of US Democracy: Assessing the Decision’s Impact 15 Years Later. New York: Roosevelt Institute.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Bilal Baydoun, Shahrzad Shams, Jake Grumbach, Bree Bang-Jensen, Suzanne Kahn, Aastha Uprety, Katherine De Chant, and Noa Rosinplotz for their feedback, insights, and contributions to this paper. Any errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies are the author’s alone.