Increasing Wages for Low-Income Workers Is Key for a Full Economic Recovery

April 4, 2022

By Joana Duran-Franch, Ira Regmi

Wage growth is long overdue in our economy, in which low-income workers’ wages have remained stagnant since the 1980s. Despite recent gains, wage inequality—or the gap between those who earn the least and the most—remains at very high levels, exacerbating other forms of inequality characterized by capital and wealth. However, while there has been debate about how much workers’ wage gains have been compromised by rising inflation today, we continue to find evidence of average real wage growth for low-wage earners. This real wage growth is essential for an equitable and inclusive economy and necessary for a robust economic recovery.

Real Wages Have Increased for Those at the Bottom of the Income Distribution

Average real wage measurement during recessions and recoveries can be confounded by rapid changes in workforce composition arising from workers flowing in and out of the labor market. Taking these challenges into consideration, last fall we began analyzing real wage growth before and during the pandemic by using occupations—pooled in percentiles—as the unit of analysis. We found that as of October 2021, between roughly 56 and 57 percent of occupations, concentrated mainly in the bottom half of the income distribution, saw real hourly wage increases in the past two years, even with higher-than-anticipated inflation in 2021.

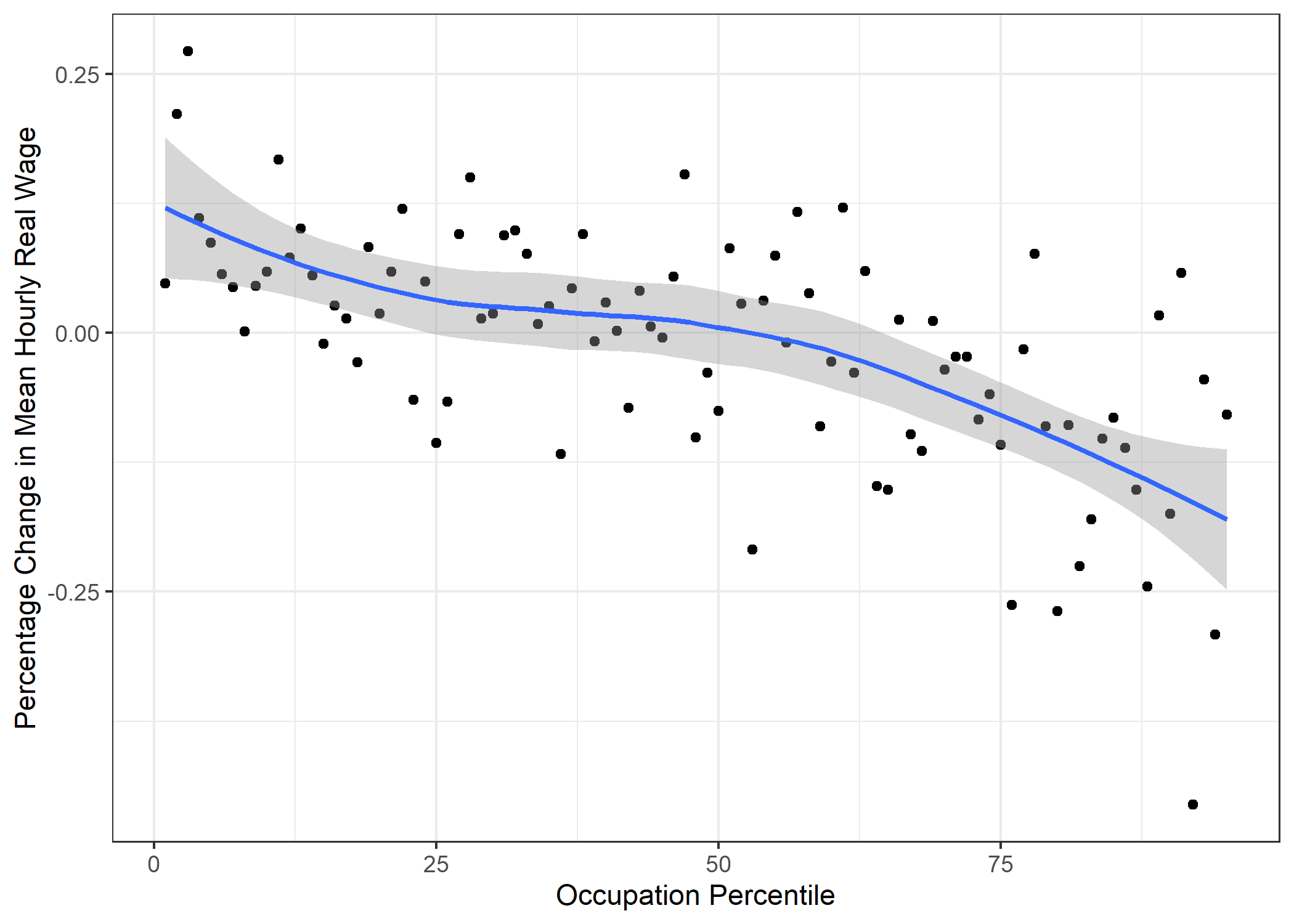

Using the same methodology as our previous analysis, we continue to find higher real wages at the bottom of the wage distribution relative to pre-pandemic levels (see Figure 1). Other studies, including those by Arindrajit Dube, Kathyrene Russ, and the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, have reached similar conclusions regarding low-wage earners. Variation in the choice of units relevant to the handling of composition effects, use of different data sets, and other procedural differences are likely to yield somewhat different conclusions.

Comparing average wages by occupation from a period immediately before the onset of the historic pandemic-driven recession in January and February 2020 to wages in January and February 2022, we find that 47 percent of all occupations are seeing real wage gains on average. Moreover, these occupations account for 49 percent of total nonfarm employment in January and February 2022.

Figure 1. Average Hourly Real Wage Changes by Occupational Percentile, January and February 2020–2022

Source: Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group extracted via IPUMS and US Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in US City Average.

Note: Analysis includes all non-farm employees ages 16 and older. On the x-axis, similar occupations (in terms of mean hourly real wages) are arranged by the January and February 2020 Mean Hourly Wage. Each point refers to an occupation percentile. Mean hourly real wage changes are approximated using log differences. Top-coded hourly wages are multiplied by 1.4, as in Lemieux (2006). The graph displays a smoothing function of the changes (blue) as well as 95 percent confidence bands (areas in gray).

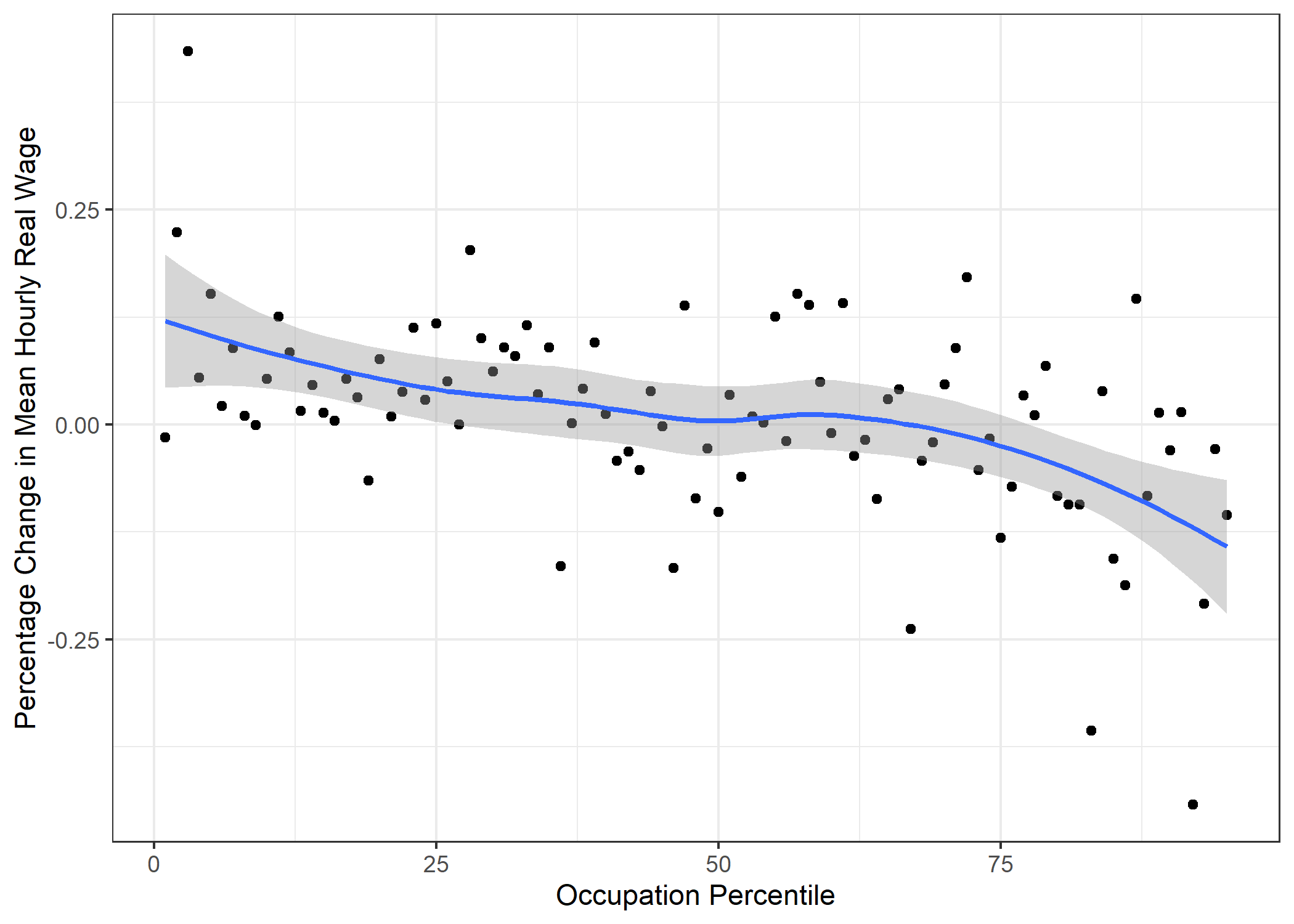

Because of composition effects, there is an extra note of caution to be taken when looking at Figure 1. Early in the pandemic, low-wage earners disproportionately lost their jobs, increasing the overall average wage. As employment in early 2022 still remained below pre-pandemic levels, it is possible that these average wages were up only artificially. To account for this composition effect, we compared wages in early 2021 to early 2022, as workers reentering the workforce should be artificially adding downward pressure on average wages in this period. Figure 2 shows that even when that is the case, we still observe real wage gains at the lower end of the wage distribution.

Figure 2. Mean Hourly Real Wage Changes by Occupational Percentile, January and February 2021–2022

Source: Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group extracted via IPUMS and US Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers: All Items in US City Average.

Note: Analysis includes all non-farm employees ages 16 and older. On the x-axis, similar occupations (in terms of mean hourly real wages) are arranged by the January and February 2020 Mean Hourly Wage. Each point refers to an occupation percentile. Mean hourly real wage changes are approximated using log differences. Top-coded hourly wages are multiplied by 1.4, as in Lemieux (2006). The graph displays a smoothing function of the changes (blue) as well as 95 percent confidence bands (areas in gray).

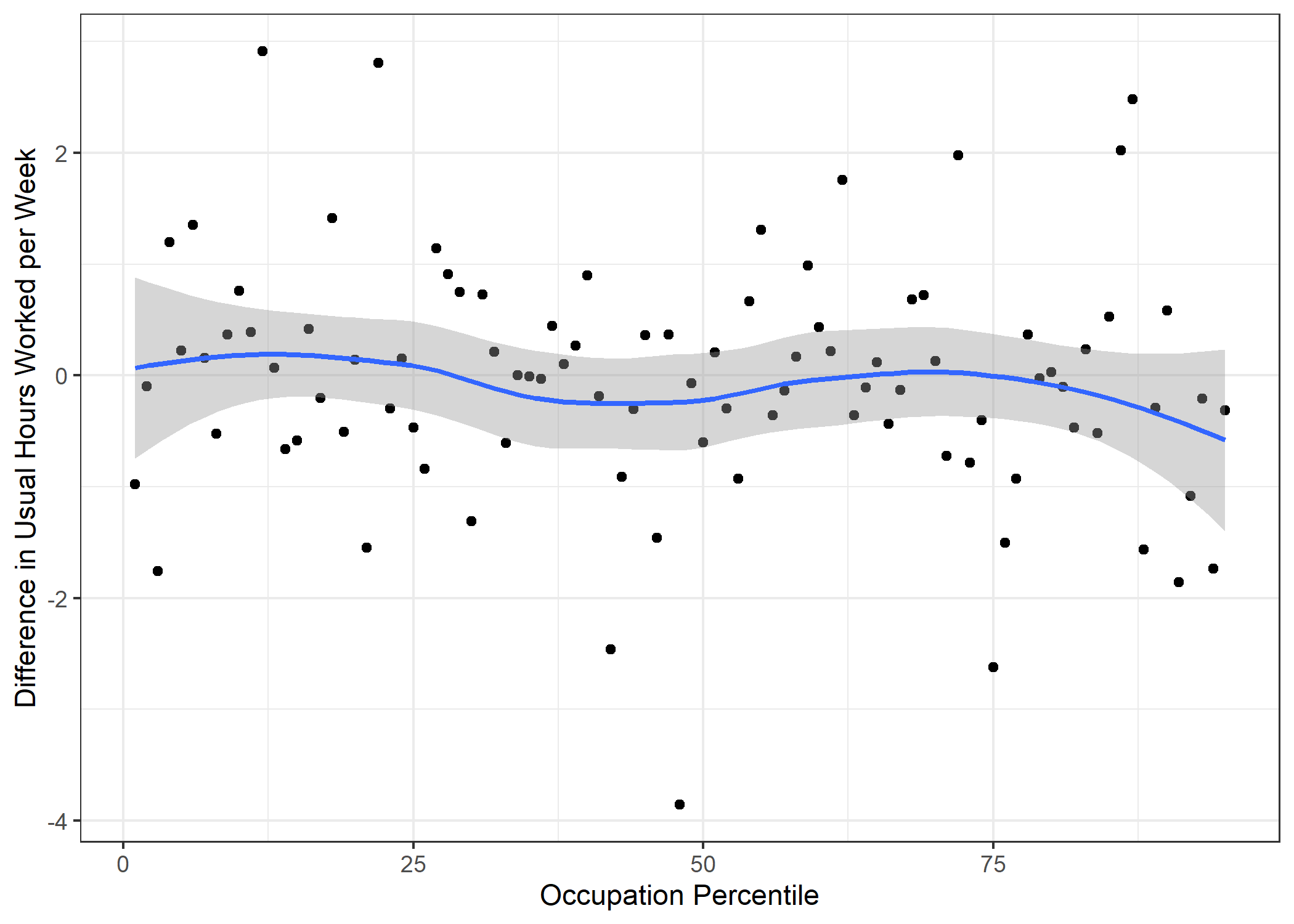

To ensure that hourly wage increases translated into actual labor income gains for low-income workers, who often tend to work part-time or inconsistent hours, we also checked the evolution of usual hours worked by occupation percentile over the same period. As Figure 3 shows, on average along the distribution, usual hours worked per week for those employed have not changed relative to pre-pandemic levels, implying that there have been real labor income gains at the bottom of the wage distribution.

Figure 3. Changes in Mean Usual Hours Worked per Week by Occupational Percentile, January and February 2020–2022

Source: Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group extracted via IPUMS.

Note: Analysis includes all non-farm employees ages 16 and older. On the x-axis, similar occupations (in terms of mean hourly real wages) are arranged by the January and February 2020 Mean Hourly Wage. Each point refers to an occupation percentile. The graph displays a smoothing function of the changes (blue) as well as 95 percent confidence bands (gray).

Wage Increases Promote Equity and Bring Us Closer to a Full Recovery

Increasing wages for those earning the least is fundamental to ensuring an equitable economy that leaves no one behind. Wage increases among those who earn the least helps Black, brown, Latinx, and gender and sexual minorities most, as these communities are disproportionately represented in low-wage populations. For example, approximately 60 percent of low-wage earners are women, and wage increases at the bottom of the income distribution are likely to benefit nearly one-third of Black Americans and a quarter of Latinx Americans.

Moreover, beyond the equity-related benefits of higher wages, increasing wages for low-income workers in particular also provides benefits for the economy as a whole. It can be difficult to isolate the empirical effects of wage gains via market forces on living standards given the various moving parts, such as nonwage gains, fiscal stimulus, and price volatility. However, by drawing parallels to a policy-induced phenomenon like minimum wage increase, which by construction raises the incomes of low-wage workers, we can identify the potential impact of real wage gains for those who earn the least.

Previous research on minimum wage increases illustrates that the additional income arising from raising the minimum wage represents a shift of income from profits (not likely to be spent immediately) to low-wage workers, who tend to consume it immediately. This feeds back into the economy as a result of increased aggregate demand. Furthermore, the extra consumption is expected to be greater than if the incomes of those with already higher wages were to increase. The marginal propensity to consume, which is indicative of the proportion of disposable income that individuals spend on the consumption of goods and services, tends to be higher for lower-income workers. There is also evidence that individuals with lower wealth have higher marginal propensities to consume than wealthier ones; or that those with low wealth-to-income ratios have higher marginal propensities to consume. Therefore, rather than being a cause of alarm related to inflation, wage gains for low-income workers are necessary for a strong economic recovery.

Moreover, recent studies find that spending on services, particularly retail and food services, is likely to increase following a minimum wage increase. This would be a welcome development, as the pandemic-driven slowdown disproportionately affected the service industry. Increased spending could catalyze a full recovery of the service sector. A majority of low-paying occupations are concentrated in the food and retail industries, both of which primarily employ low-wage workers. Increased demand in these sectors could also increase the demand for labor, potentially restoring pre-pandemic employment rates.

This is particularly crucial in the current context, given that most of the labor market slack is concentrated in occupations at the lower end of the wage distribution. For example, in January and February 2022, overall employment was 0.9 percent below its level in the same period in 2020. In contrast, employment in occupations at the 25th percentile of the wage distribution was 4 percent below its level during the same period in 2020.

Examining the parallels to the effects of minimum wage increases suggests that wage growth at the lower end of the distribution is indispensable to reaching a full and equitable economic recovery. In this context, it becomes even more important to celebrate wage gains for low-wage workers in connection to macroeconomic growth in and of itself.

The current period of strong, sustained economic growth represents an opportunity to continue advancing much-needed employment and wage gains for low-income and historically marginalized workers. However, for those who earn the least, the absolute value of real earnings is still largely deficient despite the undeniable gains. If anything, the insufficiency of wages at the bottom of the income distribution, even in the face of rapid gains, alludes to the severity of the crunch faced by low-wage earners in pre-pandemic times. Macroeconomic policy that continues to facilitate a tight labor market and the wage growth that has accompanied it in the past two years will help address the four-decades-long negligible wage growth. We should celebrate recent wage gains as an important milestone on the right trajectory, but they are not the end goal: We must ensure that wages for those who earn the least continue to increase.