As Inflation Slows, Don’t Credit the Fed

February 17, 2023

By Ira Regmi

In a December 2022 paper, The Causes of and Responses to Today’s Inflation, Joseph Stiglitz and I argued that excess inflation over the past year was largely a sectoral and supply-side issue rather than a generalized increase in prices caused by aggregate demand or the labor market. One goal of the paper was to ensure that as inflation slows, the Federal Reserve’s aggressive and recession-risking interest rate hikes don’t get undue credit. As we begin to see a reversal in inflation, it is important to understand the role that monetary policy may or may not have played in slowing down the acceleration of prices.

In January 2023, the increase in Consumer Price Index (CPI) for the “all items” category slowed to 6.4 percent over the last 12 months—the lowest since October 2021. Month-over-month CPI increased by 0.5 percent, mostly led by shelter after increasing by only 0.1 percent in December 2022. Slowing inflation has not resulted from changes in demand or the labor market but because supply chains are gradually easing and shortages are abated. Yet the Fed continues raising interest rates and flags an “out-of-balance” labor market as too tight. As overall inflation slows—primarily in response to movements in energy, food, and core goods prices—and with costs of nonhousing services not accelerating, there isn’t a strong argument for curbing inflation by reducing wages and jeopardizing jobs.

Excess Demand Drove Neither the Rise nor the Fall of Inflation

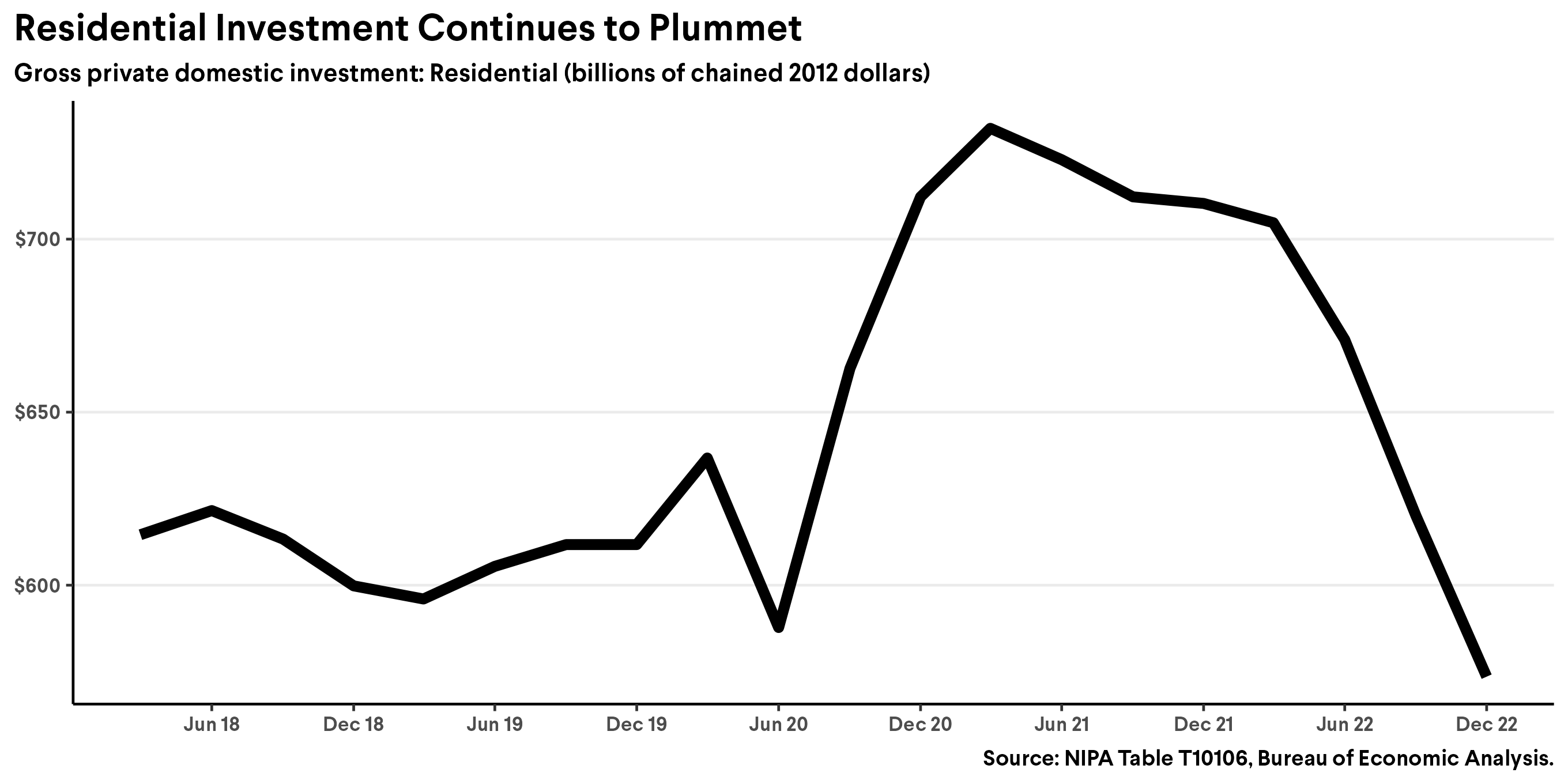

Our paper demonstrated that components of aggregate demand and output did not increase substantially enough to indicate that demand was driving inflation—in fact, they even remained largely at or under pre-pandemic trends. Further, there isn’t evidence that a reduction in aggregate demand is slowing inflation. Real GDP increased in the last quarter and consumption levels have largely remained at the pre-pandemic trend. Real government spending and net exports have increased. Through most of 2022, private domestic investment declined (Figures 1 and 2)—led by plummeting residential investments—but it has recently stabilized. The trajectory of these demand components doesn’t point to any further reduction in demand; therefore, if prices are coming down without a change in demand, it is unlikely that demand was the root cause of inflation in the first place.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Supply-Side and Sectoral Adjustments Are Driving Down Excess Inflation

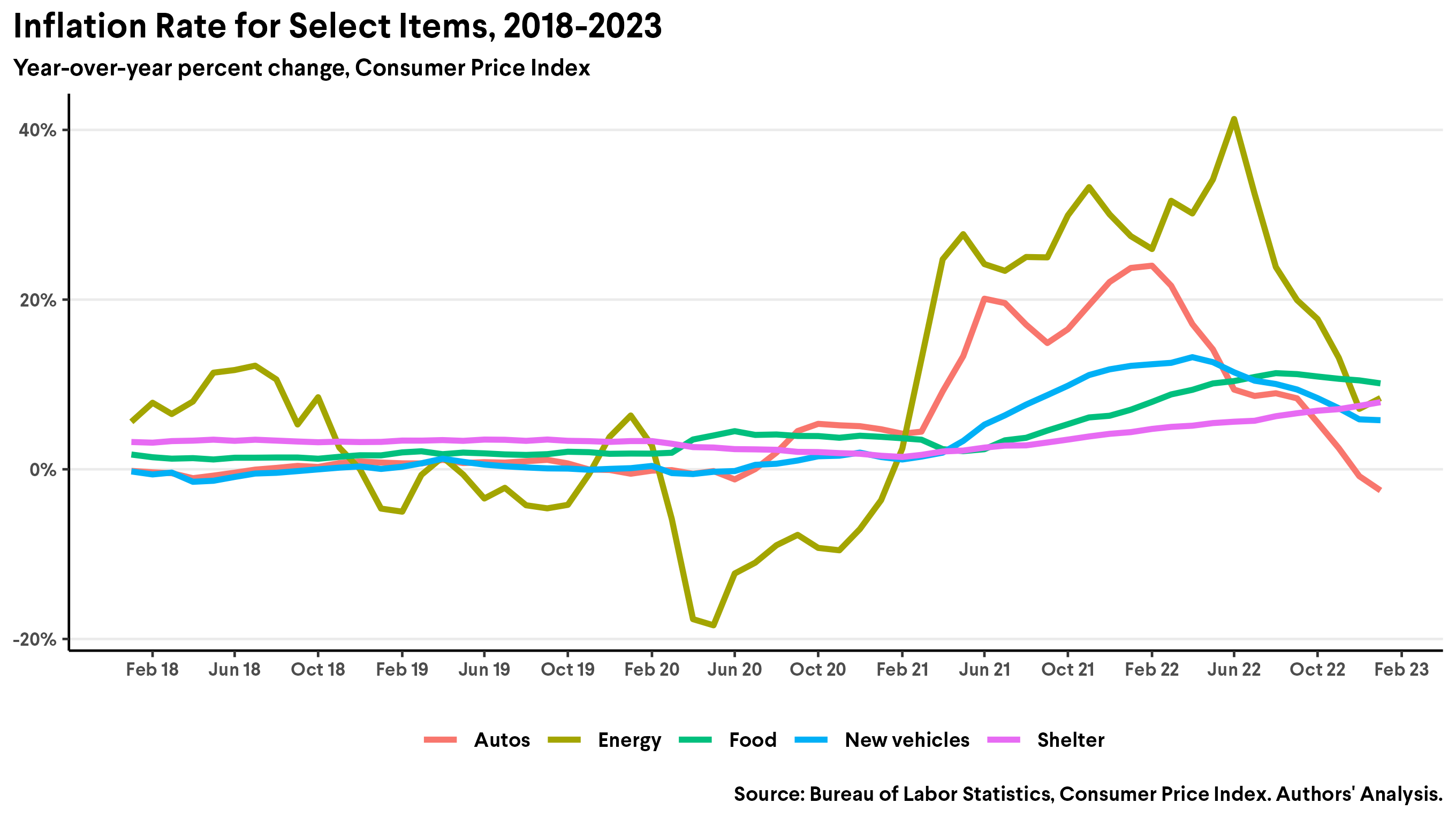

On the other hand, we have witnessed substantial changes in sector-specific supply-side issues driving inflation. Figure 3 shows a sharp and continuous decline in energy and auto prices as well as a moderate deceleration in food prices.

Figure 3

In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the US and the European Union banned imports of Russian oil, which sent energy prices soaring across the globe. Since the initial supply shock, energy prices have been falling due to various factors that have nothing to do with domestic monetary policy in the US. Extreme energy-saving measures led to a 12 percent decrease from the period 2019-2021 in European energy demand. At the same time, European countries replaced 80 percent of their Russian gas supply with natural gas imports, mainly from the US and Norway. The decline in energy prices has not been accompanied by a decline in domestic US demand, indicating that energy prices are determined in the global market and are subject to geopolitical crises. Automobile prices declined in January 2023, led mostly by used vehicle prices and deceleration in new vehicle prices. Consumption expenditure on automobiles has not seen a meaningful change, and the persistence of auto demand while prices fall points to the role of supply chain issues that took a long time to resolve in the wake of the pandemic.

There Is Still Room for Inflation to Slow Down without Sacrificing Workers

Corporate profits remain historically high, even as they’ve stabilized mildly. There is still plenty of room for corporate profits to decrease and create disinflationary pressure that brings prices down. The rapid rise in profits, margins, and markups all point to a generalized increase in market power that allowed firms to increase prices more than the rise in costs—a phenomenon that Vice Chair of the Federal Reserve Lael Brainard described as a price-price spiral. A prime example of this corporate profiteering is in the energy sector; in the midst of a global energy crisis, oil majors have kept high refining margins, which they plan to keep up this year, and made over $200 billion in 2022.

In addition, the inherent volatility of fossil fuel from geopolitical and climate risks and commodity market speculation contribute to rising prices and will not be curtailed through interest rate hikes.

That volatility in fossil fuel prices can lead to the kind of month-over-month spikes we saw in February’s CPI release. Rate hikes also cannot stop rising energy costs from seeping into other prices. A recent paper by Isabella Weber and others demonstrates that some prices, including energy, have a larger impact on the general price stability, and thus interest rate hikes will not be able to address inflation in the face of large sectoral shocks such as pandemics, geopolitical disturbances, or climate change.

As shown above in Figure 3, shelter costs (both rent and housing) continue to rise, and drove most of the increase in core prices in January 2023. The full effect of interest rate hikes is felt over a long period of time, especially in the housing market, and is therefore unlikely to help bring inflation down in the present. Instead, interest rate hikes are likely to worsen the housing crisis in the long term by exacerbating the housing shortage; the number of new, privately owned housing units started has dropped sharply since August 2022. In the absence of a robust public housing mechanism, plummeting housing starts will aggravate the cost-of-living crisis in the future.

The decision to fixate on wage growth, despite seeing inflation respond to other causes, suggests that perhaps the Fed has “a secret wage target,” as Mike Konczal has put it. Targeting wage growth irrespective of its relation to inflation is an anti-labor, anti-Black, and anti-working-class policy. A labor market characterized by large racial gaps in income, weak unions, declining labor share of income, and a lack of worker power is not susceptible to the same wage-price dynamics from a few decades ago. While the current labor market has improved since 2019, maintaining high wage growth is necessary to compensate for the decades of sluggish wages and declining real wages, as seen in the first half of 2022.

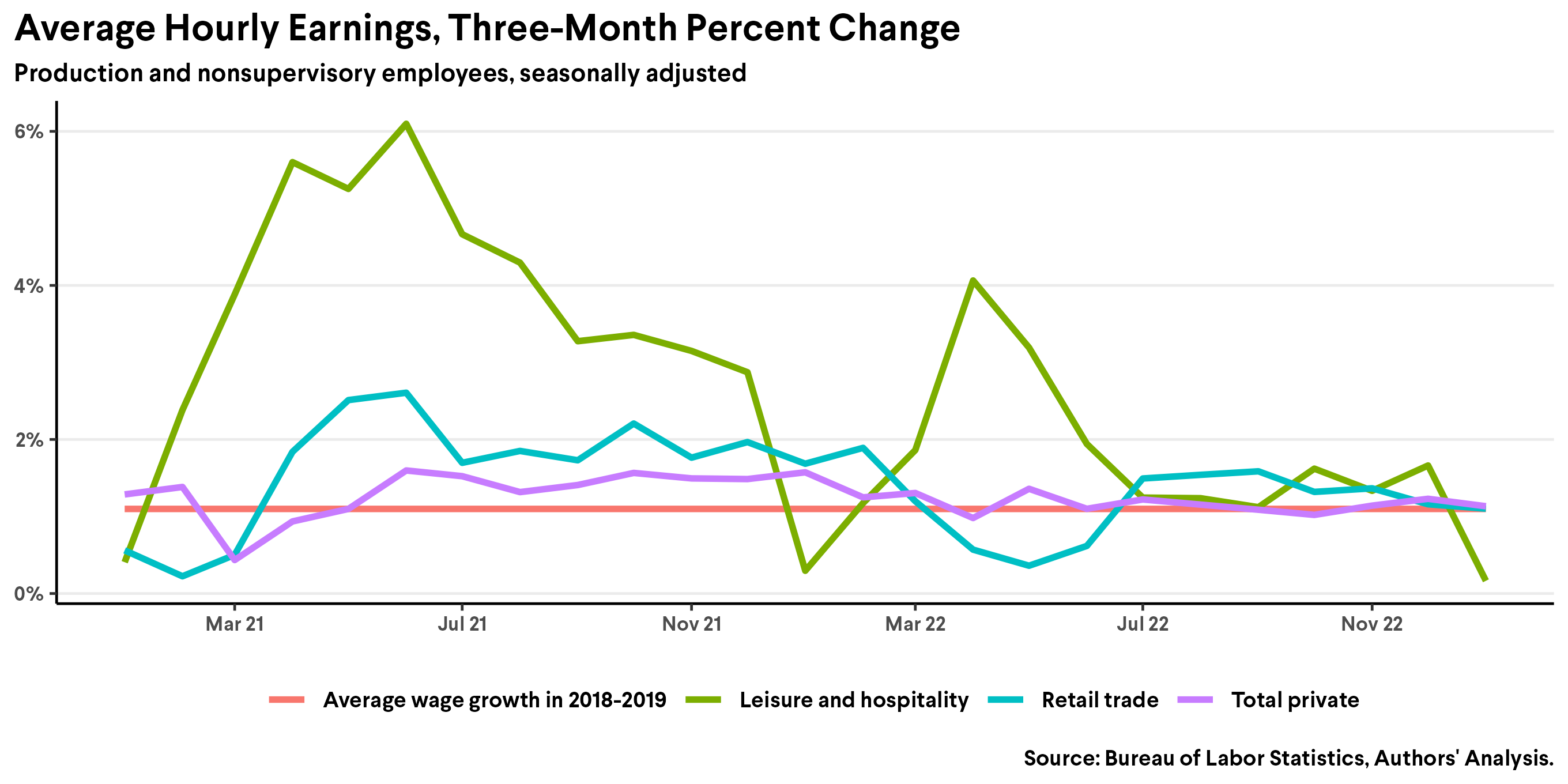

Already, in response to an aggressive tightening of monetary policy, nominal wage growth has moderated in recent months, though the Fed still considers the levels of wage growth “too high.” The three-month percent change in average hourly earnings from the Employers Cost Index has fallen toward pre-pandemic levels, especially for workers in service occupations. The three-month percent change for total private and retail trade workers has moderated, while dropping sharply for leisure and hospitality workers (Figure 5). The three-month percent change for all production and nonsupervisory workers has already dropped to the average rate of wage growth in 2018-2019.

Figure 4

We Need an Economy That Can Sustain Wage Growth

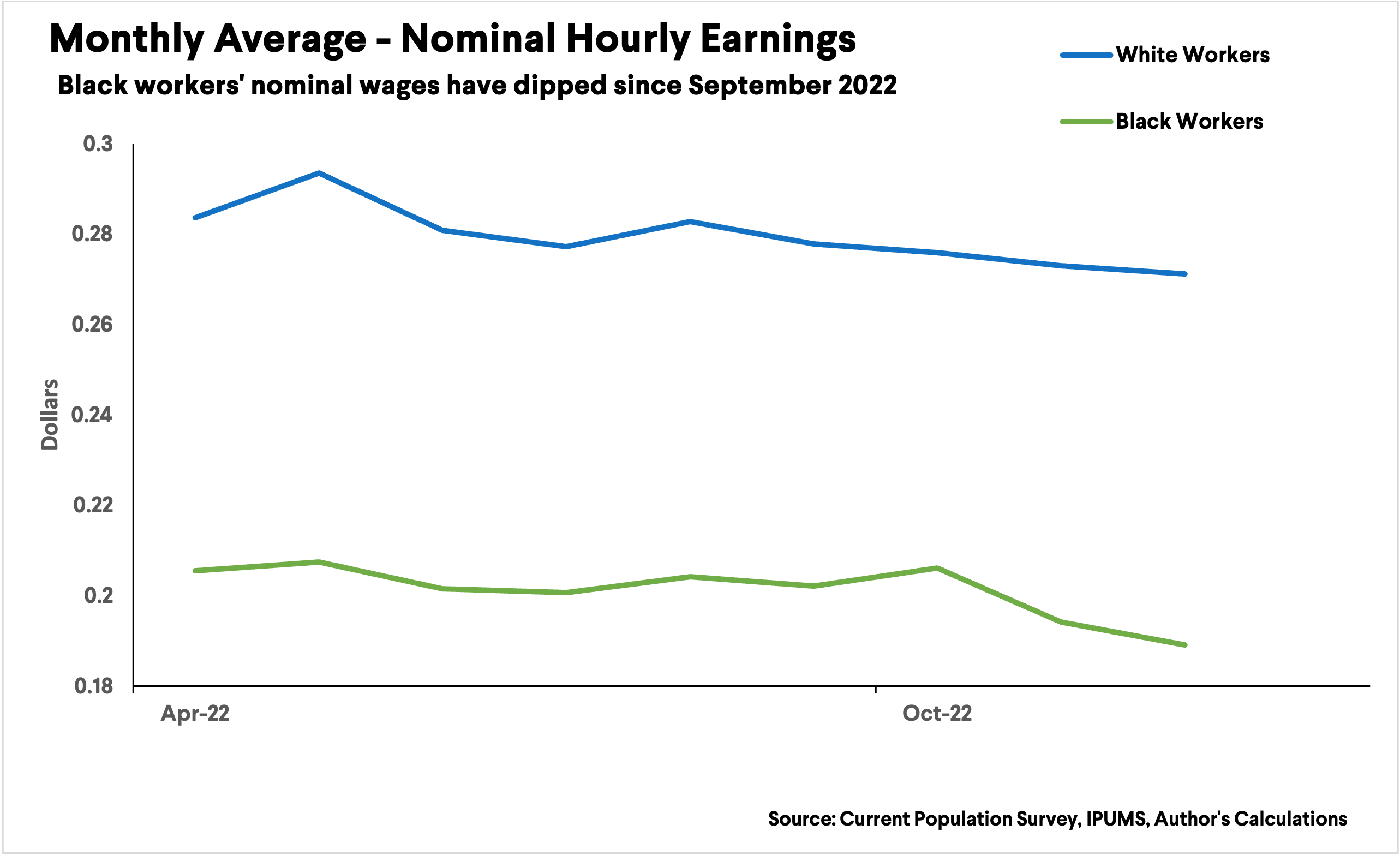

As has historically been the case, low-income and Black workers are the first to witness a drop in earnings as the Fed tries to slow the economy down. While monthly earnings data can be volatile, it is worth noting that average hourly earnings in December of 2022 dipped sharply for Black workers, while the change in hourly wages for white workers was insignificant (Figure 5). Nominal wages for Black workers have always been consistently lower, with the gap closing only during times of strong economic growth.

Figure 5

In times of economic crisis, workers of color are also often the first to lose their jobs. As of January 2023, Black women’s and men’s unemployment rates were at 5.2 and 5.6 percent respectively—much higher than the overall unemployment rate of 3.4 percent.

In the immediate future, sacrificing workers will not lead to price stability. To curb the kind of inflation we’re seeing today, government must address geopolitical volatilities and pandemic-related disruptions and implement rent and price controls and inflation relief funds to shield lower-income individuals from rising prices. In the longer term, robust social housing, public provision of essential utilities, a swift and just transition to renewable energy, sectoral bargaining, and a reduction of corporate profits will be key to maintaining economic stability without harming workers with needless recessions. Monetary policy alone is an insufficient solution, and it can cause more harm than good.