For a Full Economic Recovery, Debt Is No Object

August 6, 2020

By Mike Konczal

As COVID-19 continues to spread, and as Congress considers its next round of support, one fact is worth remembering: A higher level of debt would in no way be a hindrance to addressing this crisis. In a climate of low interest rates and deep economic suffering, deficit and debt shouldn’t be a factor. Here’s why:

Low Interest Rates Mean Low-Cost Borrowing

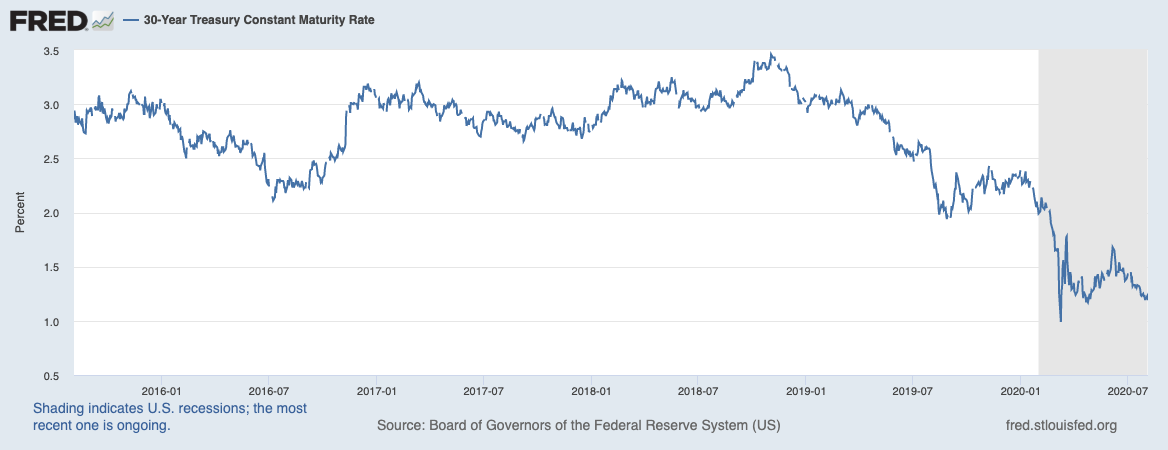

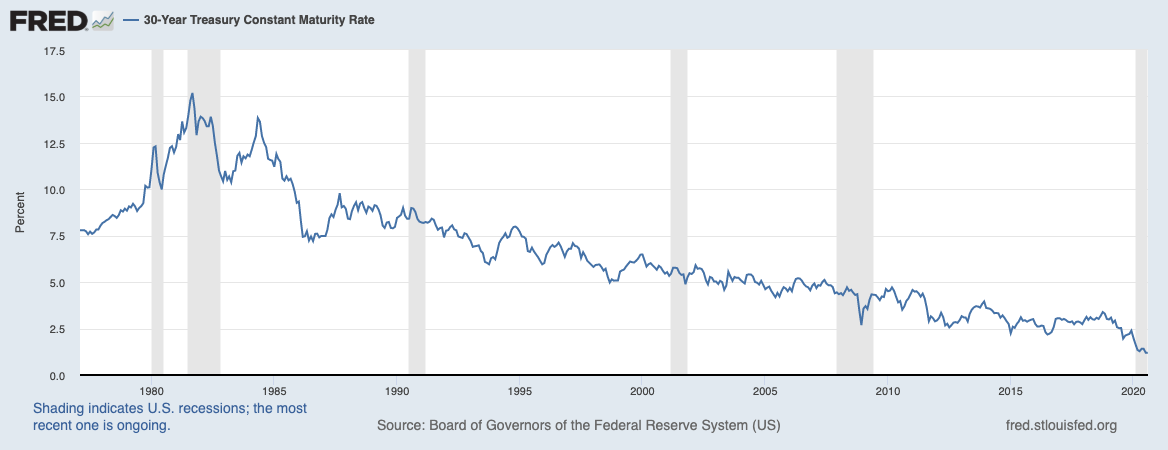

As Figures 1 and 2 show, interest rates on 30-year government debt have declined to record lows since the beginning of this year and are now approaching zero—following a secular decline in rates since the 1980s.

Rates are, even more surprising, as low or even lower than during the initial panic in March of this year, even as deficits have increased.

These low rates persist even as it’s clear the recession will not have a quick recovery, and that we will have large deficits for the foreseeable future. Any concerns about the current or future deficit have not manifested in interest rates. Moreover, inflation has collapsed. Early in this crisis, some worried about a “supply-side” recession, driven especially by issues relating to supply chains. While there have been problems producing much-needed medical equipment, the primary challenge facing the macroeconomy has been a deficiency in demand for goods and services.

Amid this lack of creeping inflation, the Federal Reserve has taken significant action to reduce interest rates for the country, including new rounds of quantitative easing and the extension of those programs to other forms of debt. This has done the important, immediate thing that the Federal Reserve can do: lower rates and collapse the premium the financial sector requires in a crisis. However, these actions are insufficient without fiscal policy. The Fed’s commitment to keeping interest rates low for a long time locks in these rates, and the collapse in inflation shows that markets are not worried about these rates being too low for too long. Whatever worry there is about debt isn’t coming from the financial markets.

Spending Money Works

Though it had a difficult and rocky launch due to the anemic and underdeveloped nature of our social insurance system, as well as the vast amount of need the pandemic created, the CARES Act bolstered spending on a scale rarely seen in our country. Delivering around a trillion dollars in aid over three months, it pushed back successfully against the worst of this depression. Even in a depression with high unemployment, income rose in aggregate for individuals, and poverty either stayed the same or even declined.

This is the promise of social insurance and active Keynesian macroeconomic management. Even as market income falls in a recession, expenditure can be maintained in order to ensure that a recession doesn’t perpetuate itself. Providing income security to everyday people with stimulus checks and expanded unemployment benefits helped keep millions afloat and lessened macroeconomic harm; it can do so again—and better than the first time.

The Senate’s refusal to provide fiscal support to states and municipalities (as the House-passed HEROES Act sought to do) stands out as a failure, but such relief is still possible and necessary.

We Still Need Stimulus and Public Investment

Mounting COVID-19 case counts have dashed formerly prevalent hopes of a “v-shaped” recovery. Even positive forecasts see unemployment likely to remain above 10 percent—worse than the worst of the Great Recession—well into next year.

Spending to stabilize the economy will be necessary in the meantime. To transition our economy and employ workers in new fields, we must also make overdue investments—including in decarbonization and climate mitigation. The arguments for those investments being debt-financed were strong last year; they’ve only become stronger during this high-stakes moment.