How to Tax the Ultrarich

January 29, 2026

By Brian Galle

This is a web-friendly preview of the report.

America’s wealth has concentrated to historic levels. The top 0.1 percent—roughly 340,000 people—now hold $1 in every $6 of private US wealth (or roughly $23 trillion). That concentration isn’t just about money; it’s about power. Vast, inheritable fortunes shape media and other core civic institutions and are increasingly insulated from tax. Recent legislation supercharged this trend with bigger capital-income breaks and a doubled estate tax exemption, while trust law loopholes let fortunes snowball across generations. The result is the rapid formation of dynastic wealth—large, inherited private empires—that widens fiscal gaps and adds to the deepening democratic crisis.

This report outlines the reasons and methods for taxing the wealth of the ultrarich. It proposes a fair share tax (FAST). This reform would change the taxation of investments and inheritances to: (1) hit only the ultrarich, (2) defuse the valuation and liquidity headaches that sank earlier proposals, (3) close estate and trust loopholes, and (4) survive potential constitutional scrutiny in the wake of the US Supreme Court’s 2024 decision in Moore v. United States.

What’s Broken in Today’s Code

The realization rule. Investment gains are taxed only when sold, or “realized,” which incentivizes ultra-wealthy investors to defer sales indefinitely. And at death, basis step-up (the process that resets an asset’s taxable value when it is passed on), permanently excludes prior lifetime appreciation from income tax.

The formation of dynasty trusts. Deferral encourages holding assets indefinitely, starving the Treasury while trillions accumulate inside trusts engineered to dodge estate and generation-skipping taxes.

Extreme wealth affords immense power. The ultrarich don’t consume their wealth; they use it to shape our political and economic systems to their liking.

The Fair Share Tax (FAST) Plan

FAST is a realization-based reform that targets extreme wealth by ensuring the ultrarich pay tax on large investment gains, not just on wages. It applies to households with more than $15 million in lifetime investment gains and collects tax when assets are sold. A taxpayer’s obligation at sale under the FAST framework is equal to the amount they would have paid under an annual tax on changes in wealth (in excess of $15 million), plus interest at a rate determined by the asset’s own growth rate. Since the tax obligation grows at the underlying asset’s rate of appreciation, delaying a sale or passing assets on does not reduce the tax owed.

What It Covers

- The sale and disposition of assets.

- Work-arounds that mimic sales (e.g., related-party “income stripping” or large special dividends from closely held firms).

- Gifts and bequests: Liability sticks with the asset; death does not reset the valuation. Heirs owe a realization-based inheritance tax on very large bequests and modest annual payments creditable against future liability for exceptionally large inherited holdings.

- Optional prepayment under government-set valuation rules—which is useful to the government by improving near-term budget scores and useful to taxpayers by stopping the interest clock (increasing the cost of postponement in comparison).

Why It’s Valuable

- Constitutionally resilient: FAST taxes only realized income; it is not an annual tax on property, which the Supreme Court could potentially overturn.

- Liquidity-sensitive: Payment aligns with cash events; heirs’ annual charges are small and creditable.

- Administrative focus: Most taxpayers would not require annual appraisal; enforcement can concentrate on the top 0.1 percent.

- Anti-dynasty by design: FAST eliminates the reward for deferral by increasing the effective tax rate for more-appreciated assets; gifts, trusts, and the step-up process no longer make appreciation disappear.

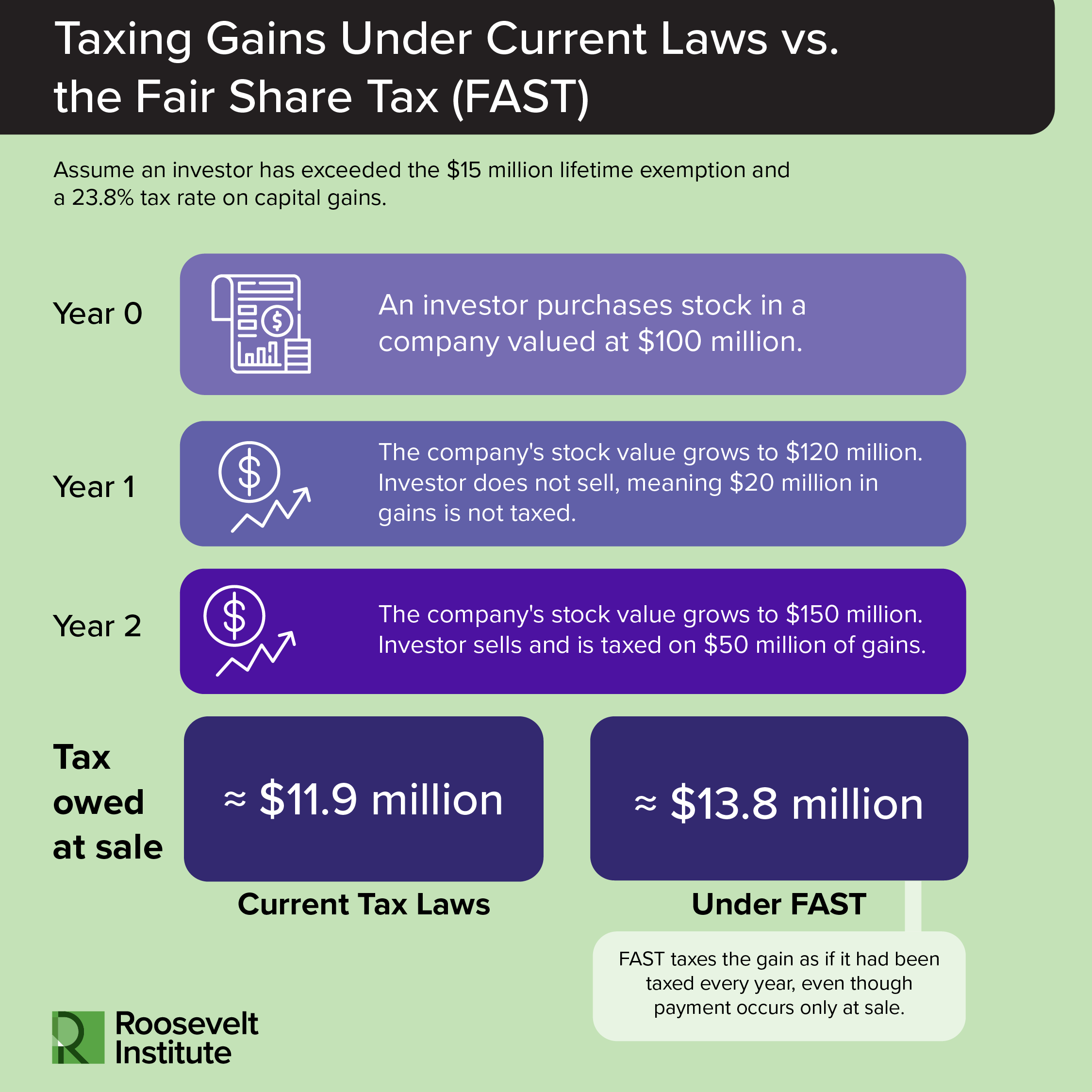

A Quick Example

Assume an investor has already exceeded the $15 million lifetime exemption and a FAST rate of 23.8 percent is in effect. The same investor purchases stock in a company valued at $100 million in year zero. In year one, the stock grows in value to $120 million but is not sold, and therefore no tax is owed. In year two, the value of the stock has increased to $150 million and is sold. To compute the tax, the taxpayer determines what they would have had left in year two under an annual tax on gains, and they owe the difference between the sale price and that amount. This can be simplified to a single formula: $150 million × (1 – ($150 million/$100 million)-0.238) ≈ $13.8 million in tax ($12.8 million in tax plus $1 million in interest). For comparison, under current tax law, the investor would only owe $11.9 million in capital gains tax at the time of sale. Put simply, under FAST, the investor is not obligated to pay anything until sale, at which point they pay the same amount they would have under annual taxation, with no reward for delay.

How FAST Compares to Alternatives

- Neutralizes the benefits of deferral. Holding longer never reduces tax; the meter runs at the asset’s own internal rate of return.

- Closes the intergenerational escape hatch. Step-up, dynasty trusts, and valuation games stop working; death is not a tax eraser.

- Matches burden to ability to pay. Those with the luxury of deferral pay for it; workers already pay as they earn.

- Budget-relevant. Optional prepayment and a 40 percent inheritance tax modeled on the FAST to replace the existing estate tax.

- What about a mark-to-market or classic wealth tax? Those options are economically attractive, yes—but FAST avoids constitutional risks post–Moore v. United States.

Conclusion

FAST is a tax for our constitutional and political moment: targeted at extreme wealth, indifferent to timing tricks, tough on dynasty-building, and aligned with realization so it is liquid, enforceable, and court-proof. It delivers the core promise of a wealth tax—making the ultrarich pay on the growth of their fortunes—without the annual valuation and constitutional pitfalls that have stalled prior efforts.

Suggested Citation

Galle, Brian. 2026. How to Tax the Ultrarich. New York: Roosevelt Institute.