It’s Time to End Joint Tax Filing

June 5, 2025

By Kitty Richards, Noa Rosinplotz

Table of Contents

Introduction

Since 1948, the vast majority of married couples in the United States have filed federal income taxes as a single unit, rather than as individuals (Kasprak 2013). In 2022, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) processed almost 55 million joint returns—a third of all returns, representing around half of filers and over 95 percent of married filers (IRS 2022). Married couples filing joint returns may seem like the natural state of things to Americans, but it makes us an outlier among our peer countries: Of the 38 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, only 9 do not use the individual as the sole tax unit (OECD 2024).

The primary justification for a joint filing regime is that it accurately represents a couple’s “pooled resources.” Under this theory, individual filing is an inaccurate measure of resources for married couples because married partners have joint control over their combined incomes, share equally in the benefits of household resources, and are able to afford higher standards of living due to the economies of scale in a household.1

Further, marriage is afforded a sociocultural premium not given to other types of economic households (roommates, for instance, or unmarried partners), and lawmakers have long presented joint filing as a way of preserving so-called family values (Richards 2017; Kornhauser 1999). Modern-day pronatalists have brought a renewed focus to the role of the tax code in encouraging marriage, on the premise that eliminating marriage penalties might raise the birth rate (Cohen 2024). President Donald Trump’s stated desire for a “baby boom” has been accompanied by policy proposals that hide marriage bonuses within baby bonuses: The Heritage Foundation proposes a new tax credit for married couples with children (Kitchener 2025), and American Compass proposes a baby bonus that is twice as large for married couples as for single parents (Brown 2024).

But there are major flaws with the assumption that marriage should be encouraged in the tax code, and the problems created by joint filing pose substantial barriers to women’s economic empowerment. The marriage penalties and bonuses generated by a joint filing regime have little impact on marriage rates but create significant inequities, rewarding sole-breadwinner households and punishing more egalitarian marriages, and often unequally burdening Black taxpayers. Further, joint filing raises the marginal tax rate on married “second earners”—most often married women—reducing their labor force participation and economic independence in important ways. These consequences are justified on the grounds that it is singularly important to tax married couples with like incomes alike, but this justification fails to account for important differences between couples with the same total income, relies on an outdated assumption of partnership marriage, and ignores other significant resource pooling among households. A move to individual filing, making the tax code marriage neutral and reducing tax rates on married women who work, would not only simplify the tax code but make it fairer and increase the ability of married women to participate fully in the economy.

Taxing Couples Together Involves Complicated Trade-Offs

In a progressive income tax system, where higher-income taxpayers are taxed at higher rates, the decision to combine individual income-earners into larger taxable units, such as married couples, can change the amount of tax that these individuals owe. This can happen because the couple’s combined income places them in a higher or lower tax bracket than their individual incomes or because their combined income moves them in or out of the eligibility or phaseout range for a tax benefit or limitation. This has ramifications for the household as a whole as well as for the individual earners being combined into a unit.

Joint Filing Creates Marriage Penalties and Bonuses

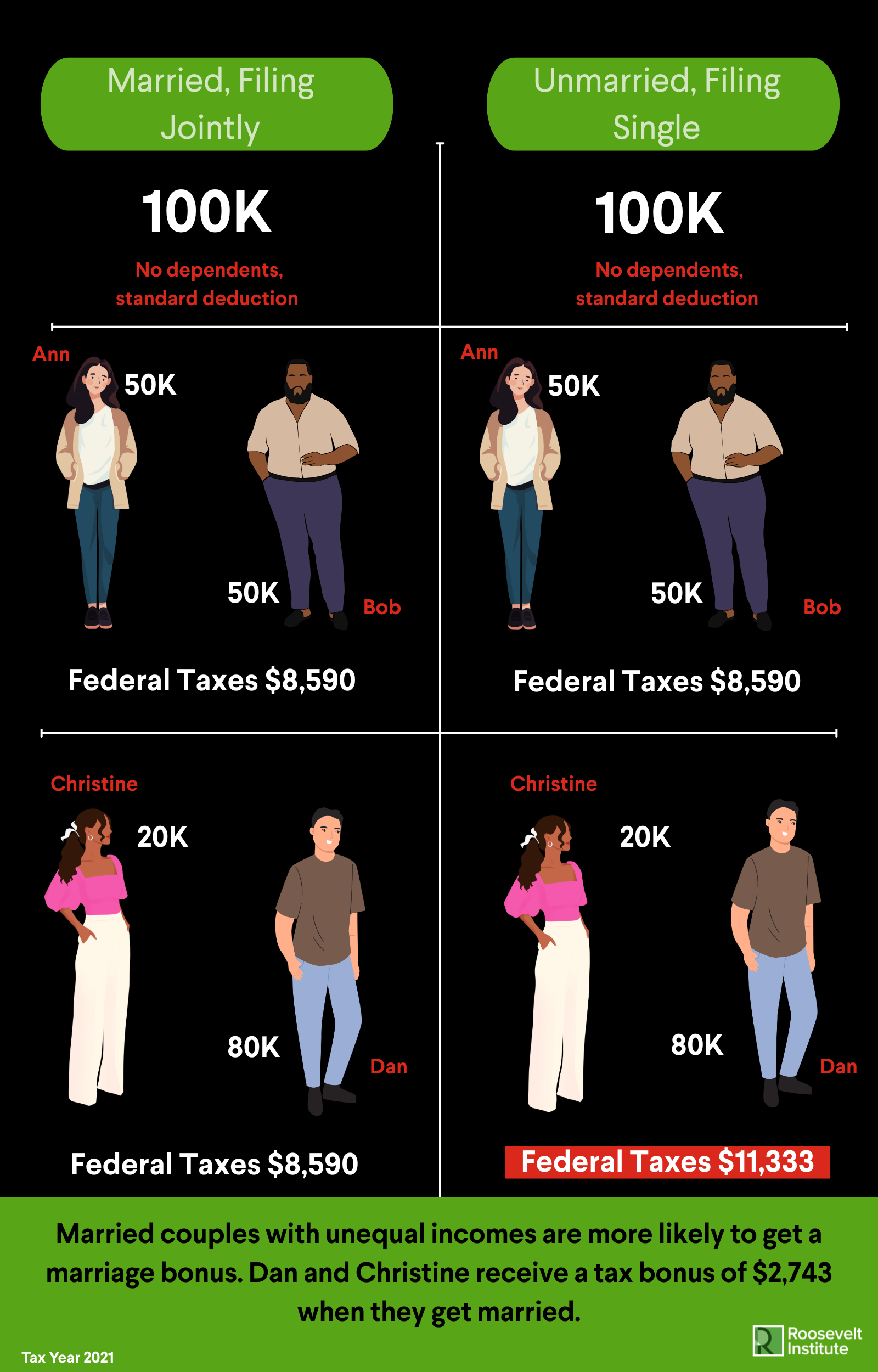

A marriage penalty exists when a married couple pays higher taxes filing jointly than they would if they each filed as single. If the tax bracket cutoffs (and other parameters) for the individual income tax were identical for singles and married couples, all couples comprising two spouses with taxable income would face a marriage penalty when filing jointly, because adding up two peoples’ incomes would push them into higher tax brackets, with smaller deductions and credits. A marriage bonus exists when a married couple pays lower taxes filing jointly than they would if they were not married and filed as single. To illustrate this, we’ll work through a few example couples with simple tax situations, using the Tax Policy Center (TPC) Marriage Calculator (TPC 2021):2

Imagine a married couple, Ann and Bob, who make $50,000 each in wages per year, or $100,000 total. They have no children or additional income and no deductions other than the standard deduction. If they were unmarried, Ann and Bob would each file as single individuals with adjusted gross incomes of $50,000 and taxable incomes after the standard deduction of $37,450. They would each see their first $9,950 of taxable income taxed at the 10 percent rate ($995 in tax) and their remaining $27,500 taxed at the 12 percent rate ($3,300 in tax), for individual tax bills of $4,295 each, or a combined total of $8,590 in tax for the couple.3 This is the same amount they owe as a married couple filing jointly: Their combined $100,000 in wages become a combined $74,900 after the standard deduction, which is twice the standard deduction for singles; the cutoff for the 10 percent bracket is twice the $9,950 cutoff for singles, for $1,990 tax on their first combined $19,900; and the remaining $55,000 is taxed at the 22 percent rate, for an additional $6,600, all adding up to $8,590. For Ann and Bob, the individual income tax code is marriage neutral.

Now imagine another couple, Christine and Dan, who also earn $100,000 total in wages per year. In this case, Dan earns $80,000 working full-time, and Christine earns $20,000 working part-time. They also have no children or additional income and take the standard deduction whether single or married. If they were unmarried, Dan would have $67,450 in taxable income after the standard deduction. His first $9,950 of taxable income would be taxed at the 10 percent rate ($995 in tax). Above $9,950, up to $40,525, he pays 12 percent ($3,669), and his last $26,925 of taxable income is taxed at the 22 percent rate ($5,924) for a total of $10,588 in federal income taxes. Meanwhile, Christine would have $7,450 of taxable income after her standard deduction, all of which would be taxed at the 10 percent rate, for a tax bill of $745.4 As an unmarried couple, Christine and Dan pay combined federal income taxes of $11,333. As a married couple filing jointly, their tax calculation looks just like Ann and Bob’s—it doesn’t matter who earns what, their income is all combined—and their total tax paid is the same: $8,590. Dan and Christine receive a marriage bonus of $2,743.

This is a function of the fact that, under current law, the standard deduction and tax brackets for married filers at this income level are double those for single filers, and Christine does not “use up” the lowest tax bracket as a single filer. When Dan and Christine get married, his income benefits from the “extra room” in the lower tax brackets. Thus, more of their total income is taxed in the 10 percent and 12 percent brackets, and they never reach the 22 percent bracket, where much of single Dan’s taxable income would otherwise land. To eliminate Dan and Christine’s marriage bonus and restore marriage neutrality, they would need to pay more in taxes than Ann and Bob, despite having the same total market income.

Since 1918, just after the beginning of the US income tax system, married couples have been able to file joint returns (Bittker 1974). However, the rate schedule for individuals and married couples was originally the same, and the joint return was largely an administrative shortcut (Beck 1990) for sole-breadwinner couples, who made up the vast majority of income tax filers (LaLumia 2006). The Revenue Act of 1948 created modern joint tax filing: a joint tax return available to all married spouses, with a different rate schedule to account for the combined tax unit.

At the core of the history of marital taxation is the notion of income splitting: A high-earning individual can reap significant tax reductions if they are able to split their income with a low-earning individual for tax purposes. Under pre-1948 law, wealthy married couples were able to split income from assets if the assets were jointly owned (or assign ownership of assets to a low-income spouse), but they were barred from reassigning labor income through accounting or contract. However, in 1930 the Supreme Court ruled that in the minority of US states with community property laws (granting an immediate ownership interest in all marital income to both spouses), half of the marital income, no matter who earned it, was taxable to each spouse. In other words, in some states, married couples could benefit from income splitting, thus receiving significant marriage bonuses (Bittker 1974). This created large inequities across taxpayers based on state of residence and led to a push by wealthy men in common-law jurisdictions for Congress to extend favorable tax treatment to them without forcing them to meaningfully cede ownership of their income to their wives (McCaffery 1997).

The 1948 married-filing-jointly rate schedule did just that by extending the benefits of income splitting to all married couples, handing out large tax cuts to married couples across the country. Sara LaLumia (2008) finds that the introduction of joint filing in the US in 1948 significantly reduced women’s nonwage income, as they immediately ceased to hold family assets for tax purposes.

From 1948 until 1969, getting married generally provided a tax bonus. In 1969, recognizing that this system often amounted to a penalty for unmarried taxpayers, Congress changed the rate schedule for unmarried taxpayers so that they wouldn’t pay over 20 percent more than they would if they were married. This, however, introduced marriage penalties for some couples (in particular, those with roughly egalitarian incomes), who would now be better off if they weren’t married (Bittker 1974).

As an example, take Ann and Bob, who incur neither a marriage penalty nor a marriage bonus under current law. Had they filed in 1999, with the exact same income and still taking the standard deduction, they would have faced a marriage penalty. If they were unmarried, they would each take the standard deduction of $4,300. Their respective remaining $45,700 in taxable income would be taxed at 15 percent for the first $25,750 ($3,862 in tax) and 28 percent for the next $19,950 ($5,586 in tax), for a total of $9,448 each in federal income taxes. Married, they take a standard deduction of $7,200 (which is less than double the standard deduction for single filers). Their remaining $92,800 in taxable income is taxed at 15 percent for the first $43,050 ($6,457.50 in tax) and 28 percent for the next $49,750 ($13,930 in tax), for a total federal income tax bill of $20,387.50—$1,491.50 more than they would have paid had they not gotten married.

In the 1980s, eliminating marriage penalties for couples like Ann and Bob, whose marriage penalty is a function of the size of tax brackets and the standard deduction, became a rallying cry for Republican lawmakers (Richards 2017). Providing a tax credit to eliminate marriage penalties was a key element of the tax law component of the Contract with America, Newt Gingrich’s landmark 1994 Republican legislative agenda (Republican Members of the House of Representatives 1994), and George W. Bush ran on a tax plan that included expensive “marriage penalty relief” (Mitchell 2000). The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 made the standard deduction, and the width of the lowest tax brackets, twice as large for married filers as for single filers. After the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in 2017, the tax brackets and standard deduction for nearly all married filers (i.e., those earning less than the $751,601 required to reach the top rate of 37 percent) are double those for single filers. These “marriage penalty relief” measures succeeded in eliminating bracket-based penalties for most filers, but they did so at the cost of providing large bonuses to married couples—particularly to those with an uneven income split.5

Further, eliminating bracket-based marriage penalties has not, in fact, eliminated marriage penalties. They persist due to other elements of the tax code, including phase-ins and phaseouts of various credits and deductions, and the availability of the Head of Household filing status for single individuals with children (TPC 2024).6

The marriage penalties and bonuses generated by a joint filing regime have little impact on marriage rates but create significant inequities, rewarding sole-breadwinner households and punishing more egalitarian marriages, and often unequally burdening Black taxpayers.

Let’s return to Ann and Bob, under current tax law. Their income and deductions remain the same, but now they have one seven-year-old child. If they were not married, and Ann had primary custody of their child, she could file as Head of Household, with a standard deduction of $18,800. Her $31,200 in taxable income would be taxed at 10 percent for the first $14,200 ($1,420 in tax) and 12 percent for the next $17,000 ($2,040), for a total of $3,460. She could also claim the entire $2,000 Child Tax Credit, reducing her federal income tax owed to $1,460. Because both the Child Tax Credit and the Head of Household filing status can only be claimed by one parent for a given child, Bob’s tax situation is unchanged from when he was single, and he owes $4,295. Their combined federal income tax bill is $5,755. If they got married, they would pay the same amount as they did without a child, minus the $2,000 Child Tax Credit: $6,590.7 Therefore, they face a marriage penalty of $835.

Remarkably, despite all of the ostensible focus on “marriage penalty relief,” under current law, the share of couples receiving marriage penalties and bonuses is nearly exactly equal. According to the Tax Policy Center, in 2018, identical shares of households—43 percent—experienced marriage penalties and bonuses, leaving only 14 percent of married couples paying the same as they would have paid as individuals. On average, the bonuses are larger than the penalties: Couples receiving bonuses had an average bonus of $3,062, while couples paying penalties had an average penalty of $2,064.

Bonuses and penalties are not randomly assigned, however. Couples in more egalitarian marriages in which both members of the couple make a similar amount are far more likely to face penalties, while couples in which one member makes significantly less than the other are more likely to receive bonuses (TPC 2024). This is visible in our example: When there is an imbalance in a couple’s income, such as for Christine and Dan, and tax brackets and deductions for married filers are double those for single filers, combining incomes will tax the higher earner’s income at lower rates than if they filed as an individual. Conversely, if the couples make roughly the same amount, then the benefit of spreading one high-earning spouse’s income across the doubled standard deduction and tax brackets disappears, and the relative benefit of allowing one spouse the advantages of the Earned Income Tax Credit or Head of Household status if the couple has children grows, generating larger net marriage penalties.

Marriage Penalties and Bonuses Exacerbate Racial Inequality

When the tax code is not marriage neutral, Black families are more likely than white families to face marriage penalties, exacerbating the existing discriminatory impacts of the tax code (Moran 2024).

Who receives a marriage penalty or bonus can be complicated, but an important trend is evident: The couples most likely to be hit with a marriage penalty are those in which the two members of the couple earn close to the same amount, and the couples most likely to benefit from a marriage bonus are those with a single breadwinner, or a very unequal earnings split. These penalties for egalitarian marriages have negative equity effects along racial lines (TPC 2024).

In her seminal work The Whiteness of Wealth (2021), Dorothy Brown highlights the many ways in which face-neutral tax provisions insidiously contribute to racial inequities. For many reasons related to structural racism, the sole-breadwinner married couple family that is preferenced by the tax code is more prevalent among white families than Black families. This means that joint filing can exacerbate existing racial wealth and income inequality, even within income classes. James Alm, J. Sebastian Leguizamon, and Susane Leguizamon et al. (2023) and Janet Holtzblatt et al. (2023) use survey data from the Current Population Survey and the Survey of Consumer Finances, respectively, and find support for Brown’s thesis: In their data, Black couples are more likely to face marriage penalties and face larger penalties as a share of income than white couples, while white couples are more likely to face marriage bonuses and receive larger bonuses than Black couples.0 This is true not only in aggregate but within income classes: Holtzblatt et al. find that for tax units with annual income between $50,000 and $100,000, Black couples, on average, faced a penalty of $358, while white couples, on average, received a small but statistically significant bonus of $61. They also find that “marriage penalty relief” measures enacted under Presidents George W. Bush and Donald Trump exacerbated these differences along racial lines.

Joint Filing Penalizes Lower-Earning Spouses

In our marriage penalty and bonus discussion, we focused on the total average effective tax rate faced by married couples across all of their income: how much total tax is paid, taking into account credits, deductions, and progressive tax rates, and what fraction of total income that represents. When thinking about the way that taxes affect decisions about working, saving, and spending, economists instead tend to focus on the marginal tax rate: what fraction of a person’s last dollar of income is owed in tax. In the idealized labor market of economic models, every worker is constantly trading off work against other pursuits and deciding whether to work another hour based on whether the additional wages are worth the loss in leisure time or domestic labor, and they calculate those additional wages after tax, at the margin.

This is fairly straightforward if labor income taxes are calculated individually for workers, but it becomes more complicated when you combine two workers into a single tax unit.

Let’s return to our imaginary couples. Ann and Bob pay the same total tax whether married or unmarried. They also pay the same marginal tax rate whether married or unmarried. If either of them earned an additional dollar, that dollar would be taxed at the 12 percent rate whether they were married or unmarried.

The same is not true, however, of Christine and Dan. As a married couple with the same income as Ann and Bob, they face the same marginal tax rate on an additional dollar of income—12 percent. But this is not the same as their marginal tax rates as single individuals. If they were unmarried, Dan would pay 22 percent on his next dollar of income, while Christine would pay only 10 percent. When a couple with a significant earnings disparity marries, the lower-earning spouse can face a significantly higher marginal tax rate than they would if they were single. Further, because of the realities of work and family life, couples may view a lower-earning spouse’s income as the “marginal” income for the family. Not only has Christine’s marginal tax rate increased by marrying Dan, but the couple may view her income as being “stacked on top” of Dan’s, and thus internally consider her marginal tax rate to be higher than his. The higher marginal tax rate faced by lower-earning spouses is known as the second earner penalty.

These second earner penalties are, empirically, quite large. The Office of Tax Analysis (OTA) (2015) found that, except for the very lowest-income couples,8 nonworking spouses face the prospect of much higher tax rates from entering the labor force than they would if they were single.9 On average, the marginal tax rate for these would-be labor-force entrants rises from 5.6 percent if single to 17.1 percent if filing jointly, and this may be a significant understatement.10 At the extremes, the increase is much higher. A nonworking spouse of someone whose salary puts them in the top tax bracket would pay 37 percent on their first dollar of income if married and between 0 percent and negative 45 percent on their first dollar of income if unmarried, depending on their Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) phase-in eligibility, for up to an 82 percent increase in their marginal tax rate.

Joint Filing Compounds Existing Gender Inequities, Disempowering Women at Home and in the Workforce

Up until this point we have referred to “second earners” in gender neutral terms, but they are overwhelmingly women. In 2022, 55 percent of heterosexual marriages had a wife who earned less than 40 percent of the household’s combined income, with 23 percent having a sole breadwinner husband (Fry et al. 2023). In only 16 percent of heterosexual marriages did the wife earn more than 60 percent of the combined household income (with 6 percent having sole breadwinner wives). In the 29 percent of marriages classified as “egalitarian” (because neither spouse earns more than 60 percent of the income), a significant number of women are likely still seen within the household as the “second earner.”11

Why are women so predominantly the second earners in heterosexual married couples? Largely because women earn significantly less than men. In the United States, due to “occupational segregation, devaluation of women’s work, societal norms, and discrimination,” women are paid approximately 18 percent less on average than similarly situated men (deCourcy and Gould 2025). The gender wage gap persists across the wage distribution, exists at every education level, and is considerably larger for women of color.

This difference is compounded by motherhood and caregiving responsibilities, and the interplay between lower market wages, larger household responsibilities, and higher marginal tax rates creates a self-reinforcing downward spiral for women’s careers and economic security and for gender equity in households.

Second Earner Penalties Reduce Married Women’s Labor Force Participation

The bulk of the empirical literature indicates that the overall labor supply elasticity to income taxes is, generally, extremely small (Saez, Slemrod, and Giertz 2012). In other words, workers do not tend to change their employment or hours worked significantly in response to changes in after-tax wages. One major exception is married women: While powerful nontax factors are also major drivers of women’s labor force participation and earnings, married women appear to respond to higher tax rates by reducing their labor force participation (McClelland and Mok 2012). The strongest effects are seen at what is known as the “extensive margin,” or the decision of whether to work at all (rather than marginal decisions about how much to work once in the labor force). In the US, the EITC literature highlights this finding. The EITC, a wage subsidy mainly available to workers with children and phased out based on household income—creating a high marginal tax rate for second earners in the phaseout range—has been demonstrated to have strong positive effects on the labor force participation of single mothers (Schanzenbach and Strain 2020) but negative effects on the labor force participation of married mothers facing the income phaseout, which more than offsets the positive labor force participation effects on their husbands (Eissa and Hoynes 2004).

Because of the outsized impact of second earner penalties on women’s labor force participation, moving away from joint filing should increase women’s market work, and this is in fact borne out in the real world. The degree of joint taxation and the resulting marginal tax rates explain a large share of otherwise unexplained variation in women’s work across countries in Europe and between the United States and Europe (Bick and Fuchs-Schündeln 2018). In 1971, when Sweden switched from a joint to an individual filing system, female employment increased by 10 percent, largely due to the reform (Selin 2013). This effect was particularly pronounced among women with high-income husbands and women with children.

The imposition of second earner penalties is not only inequitable, it is economically inefficient. One of the core principles of income taxation is that it is better, all else equal, to impose higher taxes on less-responsive behaviors, as that is how you raise the most revenue with the least economic “distortion” (Nolan 2023). In this way, joint taxation of married couples gets optimal tax policy exactly backward: It applies a higher marginal tax rate to second earners—in this case, overwhelmingly married women—who are most likely to curtail their earnings in response, and a lower marginal tax rate to higher-earning husbands, who are significantly less responsive (Bierbrauer et al. 2023). Joint filing thus creates a larger loss of labor force participation for a given amount of revenue than individual filing. Alexander Bick and Nicola Fuchs-Schündeln (2017) model childless married couples and find that a switch to individual filing in the US would increase women’s hours worked per year by nearly 8 percent.12 For this reason, theoretical welfare modeling incorporating these effects, and the trade-off women face between providing childcare themselves or paying for it with their after-tax wages, shows large welfare gains from moving to an individual tax filing system (Apps and Rees 2018).

Second Earner Penalties Magnify Within-Couple Inequality and Reduce Women’s Economic Security

As noted earlier, in addition to sex and race discrimination and occupational segregation, a significant share of the gender wage gap can be attributed to the effect of caregiving responsibilities on women’s earnings. While men actually see a small earnings premium for both marriage and fatherhood (Budig 2014; Pilossoph and Wee 2021), women face heavy penalties.

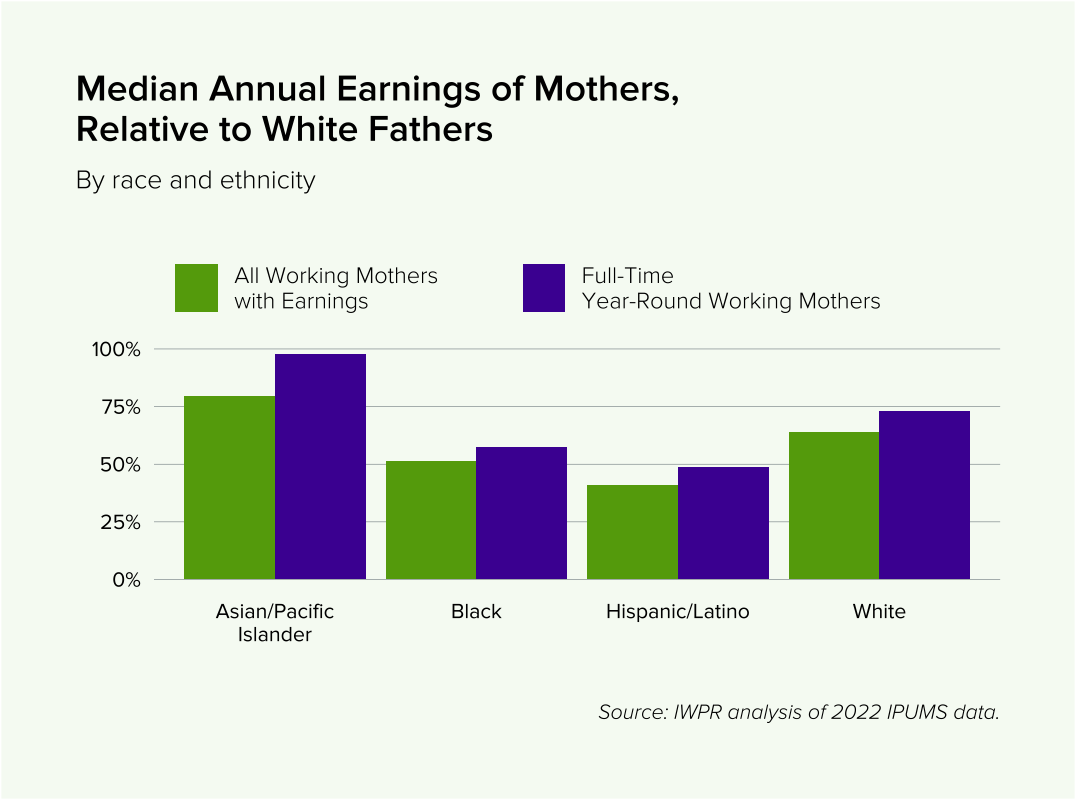

According to research from the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), in 2022, women working full-time, full-year jobs earned a median of 84 cents on the dollar compared to men, and mothers working full-time, full-year jobs earned 71.4 cents on the dollar compared to fathers (IWPR 2024). The median wage for mothers with any earnings was only 62.5 cents on the dollar compared to fathers with any earnings, as many women shift to part-time or part-year work in response to caregiving responsibilities. This gap is even starker when you compare white fathers to mothers of color:

Numerous factors, including discrimination and the burden of caregiving, cause the motherhood penalty. Women in heterosexual marriages still tend to do much more caregiving than their male partners (Fry et al. 2023), daughters are more likely to care for aging parents than sons (Grigoryeva 2017), and women are much more likely to be single parents than men (Salas-Betch 2024). It is not surprising, then, that caregiving responsibilities are much more likely to impact women’s careers than men’s (Johnson, Smith, and Butrica 2023). In 2022, 30 percent of prime-age women with minor children in the home said that they were working part time or not working due to caregiving responsibilities, compared to 3.7 percent of prime-age men with minor children (Almeida and Salas-Betch 2023). During the COVID-19 pandemic, women bore the brunt of job losses and work disruptions due to caregiving responsibilities, and it took almost three years for women to return to their pre-COVID levels of employment—nearly a year longer than for men (IWPR 2025).

These caregiving responsibilities, especially childcare responsibilities when affordable paid childcare is unavailable, can lead to prolonged absence from the labor market or career downshifting that dramatically lowers women’s earnings during the caregiving period (Johnson, Smith, and Butrica 2023). And absences from the labor market due to caregiving responsibilities, especially early in a woman’s career, do not only reduce her income at the time. They can have lasting repercussions on future income through lost earnings growth and lost retirement savings and Social Security benefits, with the lifetime income losses for earners taking time fully out of the workforce equaling two to five times the lost salary income from the period of nonwork (Madowitz, Rowell, and Hamm 2016). In addition to the motherhood earnings penalty, there is a motherhood wealth penalty, which can become especially salient when a marriage ends by death or divorce (Lersch, Jacob, and Hank 2017).

Within-couple inequality, such as imbalances in caregiving responsibilities, drives disparities in earnings, but, crucially, earnings disparities also drive within-couple inequality, as the lower-earning female partner takes on more and more household labor to allow her higher-paid husband to focus on his career.

In Career and Family, Claudia Goldin documents the rise of “greedy jobs” and how their outsized rewards shape intra-family dynamics and economic outcomes for women (Goldin 2021). She focuses on college-educated women, who should be on the same earnings track as their male peers but by midlife are far less likely to have reached the top of their fields and are earning significantly less than the men who pursued the same occupations. Goldin demonstrates that a large driver of this phenomenon, especially in the most lucrative professions, is the way in which the highest-paid jobs reward a level of time intensity and devotion to work that is impossible to achieve while sharing in caregiving responsibilities. She writes:

As aspirations for both career and family have increased, an important part of most careers has become apparent, visible, and central. Work, for many on the career track, is greedy. The individual who puts in overtime, weekend time, or evening time will earn a lot more—so much more that, even on an hourly basis, the person is earning more.

The second earner penalty created by joint tax filing magnifies this problem: The spouse of someone with a lucrative “greedy job” will receive lower market wages for additional work than their partner but face a high marginal tax rate, and the after-tax reward to work may be significantly smaller than the reward to the household of the services a nonworking spouse can provide, especially when they enable the working spouse to fully “lean in” at a greedy job. This creates a vicious cycle in which tax incentives and the realities of greedy work increase specialization within couples, leading to income gains for married men at the expense of their female partners, which further increases the reward to specialization and the size of the tax penalty for the wife’s labor force participation.

In addition to pushing women away from the careers and relationship equity they say they want (as do their partners [Pedulla and Thébaud 2015]), tax-induced reductions to women’s financial contributions to the household may disempower them within their marriages. Marjorie Kornhauser (1993) finds that lesser-earning women, and especially nonworking wives, did not have nearly as much household decision-making power as their husbands and did not feel entitled to spend “their husband’s money.” The needs or preferences of the higher-earning spouse may heavily influence other key life decisions like where to live (Foged 2016). And, of course, women who have limited individual income and savings and reduced earning potential will find it more logistically and financially difficult to end a bad marriage or escape an abusive one (Cunha 2016; Gelles 1976).

Patterns of marriage and divorce are difficult to pin down (Miller 2014), but one study of a cohort born in the early 1960s found that by age 55, 40 percent had divorced at least once (Aughinbaugh and Rothstein 2024). When a woman spends years out of the workforce or working lower-wage, flexible, part-time jobs to accommodate her husband’s high-earning “greedy work,” and then the marriage dissolves, she may have sacrificed her own future for a bargain that no longer exists. She cannot earn back her lost retirement benefits, and if she returns to the workforce or increases her hours to make up for lost income, her earning potential has been permanently reduced. When assets are split following a divorce, insufficient legal protections mean that women often lose out on their husband’s retirement savings and pensions, even when they are entitled to a share (Entmacher and Matsui 2013; Matsui 2022). It is thus not surprising that women face much larger declines in household income after a divorce than men (Government Accountability Office 2012) and a disproportionate increase to the risk of poverty (Leopold 2018).

The couples in which one member has a greedy job—and their spouse faces a high second earner penalty—are the very same couples who are likely to be rewarded, on the whole, with a marriage bonus. The patterns of penalties and bonuses created by joint filing, therefore, drive up the cost of equality in two ways. Couples with egalitarian incomes face penalties (disproportionately burdening Black taxpayers). And in couples with less egalitarian incomes, particularly those in which one member has a high-paying “greedy job,” the higher earner is rewarded with a lower tax rate, while the lower earner is penalized. On the whole, the people truly benefiting from joint filing are the breadwinners in less egalitarian couples.

Encouraging Marriage in the Tax Code Is Ineffective and Inequitable

While the behavioral effects of second earner penalties can be large and meaningful, there has historically been much more focus on the potential effects of marriage penalties and bonuses. The cultural premium on marriage, and on two-parent families in particular, has led policymakers and lawmakers to promote marriage as a policy prescription for everything from morality to economic security (Kearney 2023a). Decades of political calls for “marriage penalty relief”—including the recently proposed Make Marriage Great Again Act (2025), which would double the income tax brackets for married filers making over $751,601 collectively—demonstrate the reluctance of US lawmakers to do anything that sounds like discouraging or penalizing marriage (Richards 2017). But despite some evidence that children in two-parent households fare better (Kearney 2023b), using the tax code to promote marriage is neither rational nor desirable.

First, even if moving additional Americans into married couple households, by inducing or accelerating marginal marriages and stopping or delaying marginal divorces, would in fact produce welfare benefits to those households, there is essentially no evidence that marriage penalties or bonuses in the tax code affect decisions about marriage and divorce (CBO 1997). There are many potential reasons for this, ranging from lack of information and uncertainty about the tax code to the simple fact that most people don’t make decisions about marriage based on their tax bill (Horowitz, Graf, and Livingston 2019).

Second, there is little reason to believe that the benefits to the involved couples of marginal marriages are anything like the benefits to couples who are already married (Frimmel, Halla, and Winter-Ebner 2014). This is both because a large share of the observed benefits of marriage are likely based on selection, not causation (Ribar 2004)—people who start out richer, healthier, and happier are more likely to get married—and because people actually may be making rational, well-informed decisions about their own marriages in the first place (Barham, Devlin, and Yang 2009). For tax-induced marriages to be beneficial, you must assume that couples are making irrational decisions leading to too few marriages and too many divorces and that the benefits to marginal marriages would outweigh the real risks of abuse and instability. In reality, women in particular may be harmed when external forces induce them to marry an unstable or financially dependent partner or to stay in a low-quality marriage (Hawkins and Booth 2005), especially when the possibility of domestic abuse is present (Johnson et al. 2022). Marriage promotion schemes have long imposed paternalistic and coercive policies on low-income women of color, legislating what it means to be a family without regard for their lived realities (Olson 2005).

Finally, in the US, marriage is more common among the wealthy. In the top income quintile, 80 percent of adults aged 33–44 are married, compared to just 38 percent of those in the bottom income quintile (Reeves and Pulliam 2020).13 If we accept the notion that married taxpayers are better off—whether via selection or causation—then marriage bonuses are a tax giveaway to materially better-off taxpayers, the opposite of what a progressive and equitable tax code should achieve.

In addition to being regressive, rewarding marriage is racially discriminatory. The legacies of slavery and institutional racism have created legal and practical barriers to Black marriage (Hill 2024), and today 57 percent of white people are married, compared to 33 percent of Black people (Horowitz, Graf, and Livingston 2019). Since the majority of Americans marry people within their race (Livingston and Brown 2017) and educational group (Greenwood et al. 2014), rewarding marriage is likely only to compound existing inequities.

Given all of these facts, it is difficult to justify a system in which most couples pay significantly different levels of tax if married than if single on the basis that this may promote marriage.

Traditional Arguments for Joint Filing Do Not Hold Up to Empirical Scrutiny

The major justification for joint filing is that married couples—uniquely—act as a single economic unit with fully pooled resources and that joint household income is thus the most accurate reflection of ability to pay and relative economic well-being. Under this theory, it is worth forgoing a marriage-neutral tax code and imposing second earner penalties to preserve a couple’s neutral tax code, taxing married couples with similar total incomes similarly.

However, this analysis misses several important aspects of household finances for both married couples and unmarried people.

Unpaid, Untaxed Household Labor Is a Significant Source of “Income” to Married Households

Joint taxation assumes that taxing couples together accounts for the fact that couples with the same total income have the same total resources, regardless of the within-couple income distribution. But among couples with the same total income, within-couple income distribution in fact has major effects on available household resources.

We’ve established that joint filing has different impacts depending on within-couple income distribution: Egalitarian couples are more likely to face a marriage penalty, while sole-breadwinner couples are more likely to receive a marriage bonus. But sole-breadwinner couples, or couples with only one full-time worker, are different from couples with two-full time workers in another important respect: One member of the couple often serves as an additional “worker” dedicated to highly valuable but unpaid (and untaxed) caregiving or home production. The spouse of someone with a highly compensated “greedy job” may be particularly incentivized to specialize in household labor rather than entering the labor market, but sole- and primary-breadwinner husbands are common across the demographic spectrum, particularly for wives without college degrees (Fry et al. 2023).

Let’s return to the example couples from our discussion of marriage penalties and bonuses. Consider Ann and Bob (who each make $50,000 working full-time, for a total of $100,000) and Christine and Dan (who make, working part-time and full-time respectively, $20,000 and $80,000, for a total of $100,000). Let’s say each couple has one seven-year-old child. Christine’s part-time schedule means she makes less money, but it also allows her more time to engage in valuable home production work that would be costly to procure on the market: cleaning, laundry, managing household finances, and, especially, childcare, the market cost of which is often higher than rent and college tuition (Dutta-Gupta 2025).

In fact, many economists would classify all of this value as income—“imputed income” from home production—and add it to Christine’s and Dan’s salaries when determining the household’s total economic income (Popkin 1975). Ann and Bob have the same household needs but may need to pay specialists such as childcare providers or cleaners to fulfill them. Given this, taxing all couples with the same total market income the same amount, when within-couple patterns of earnings and home production can have major impacts on household finances, is not a compelling justification for joint filing.

“Partnership Marriage” with Pooled Resources Is Not Universal, Not Always Desirable, and Not the Only Kind of Resource Pooling

As Kornhauser (1993) described more than 30 years ago, the “partnership model” of shared resources has never been real for most married couples. In earlier patriarchal marriages, women had no rights of control over their husbands’ income or assets, either legally or factually. Among couples surveyed in the 1980s, many claimed to share their resources, but many did not—and many of those who claimed to pool all resources actually seemed to maintain significant separation (Kornhauser 1993). According to one study, only 66 percent of heterosexual married couples pooled all their money in 2021 (Pepin 2022), and there are signs that the default marital property rules may be becoming less popular. One poll found that 20 percent of married couples signed a prenuptial agreement, with adoption of prenups higher among younger cohorts: 41 percent of Gen Z respondents and 47 percent of Millennials who were currently engaged or had been married reported entering into a prenuptial agreement (Gerzema 2023). These couples file joint returns but have contracted around the legal defaults of marriage.

Although an ideal of partnership marriage with fully pooled resources seems positive, or at least benign, this may not be the case when women are encouraged to give up financial agency or intermingle their financial and legal affairs with untrustworthy partners. Systems that seem to work for healthy, happy couples can cause significant harm to individuals coping with relationships marked by abuse. About 5 percent of married filers use the married filing separately filing status each year, and while some of these are people keeping finances separate to take advantage of other tax benefits (especially income-limited deductions for student loan interest and medical expenses), a significant portion are women using that filing status to avoid interacting with their abusers, avoid liability for spousal debt, or avoid liability for illegal or fraudulent behavior perpetrated by their spouses (Fletcher 2021; Whalen 2023). These taxpayers can face significant tax penalties for using the married filing separately tax status. The tax code not only assumes married couples pool their resources but punishes them when they don’t, even if it’s for a very good reason.

Finally, prizing marriage over other forms of resource pooling is increasingly nonsensical. Since the 1990s, marriage rates have fallen, and cohabitation rates have increased (Penn Wharton Budget Model 2025). Four in ten cohabiting partners cite finances as a major factor in deciding to move in together, while only 13 percent of married couples say the same about getting married: Cohabitation, as much as or more than marriage, is a financial partnership (Horowitz, Graf, and Livingston 2019). In addition to within-household resource pooling among unmarried cohabiting romantic partners, roommates, nondependent relatives, and platonic companions, there exist countless non-household relationships with resource sharing among family members or romantic partners who live apart (Infanti 2010). None of these are reflected in joint filing, and many of them can have at least as profound an effect on “ability to pay” and material well-being as resource pooling within marriage. By prioritizing marriage over these other forms of resource pooling, not only through joint filing but through other provisions such as tax credits for dependent children, the tax code ignores important realities of modern life.

Individual Filing Would Simplify Tax Administration Without Sacrificing Revenue

Ending joint filing on its own would have significant positive equity effects. But it would also open the door to simpler and more effective tax administration, with wide-ranging benefits (Muresianu 2021). In fact, individual filing is often thought to be close to a prerequisite for a return-free filing system, in which authorities calculate what taxpayers owe based on third-party reporting and issue refunds or bills as necessary (Goolsbee 2006). In most of the (at least) 36 countries around the world that use return-free filing, the tax unit is the individual (Liebman and Ramsey 2019).

Under the current system, workers must file complicated calculations with their employers and keep their forms updated to ensure that wage withholding adequately accounts for filing status and the income of the other spouse (Ponder 2025). Couples must then come together to file their returns and hope that their withholding was sufficient to avoid penalties and secure a refund. Without joint filing, there would be no need to match married taxpayers to one another in the IRS system before computing exact withholdings for either.

Simplified—or even return-free—filing would have particular benefits to low-income taxpayers. Private tax preparation services are often extractive and unethical, costing taxpayers billions each year and intentionally steering them away from free and low-cost options (DiVito 2024; DiVito and Hughes 2023). Many taxpayers fail to claim credits they are eligible for because of lack of outreach and coordination (Robertson and Gupta 2022). Return-free filing would ensure that all taxpayers, regardless of resources, had access to the same benefits.

Without joint filing, individual taxpayers would also not have to worry about mistakes or malfeasance from their spouses damaging their own finances. When withholding is insufficient, or a spouse makes errors in reporting income or calculating deductions and credits, it creates headaches for married couples, and even greater headaches for estranged or separated spouses: In 2021 alone, the IRS received over 25,000 innocent spouse claims from people who have tax debt from joint returns with current or former spouses (IRS 2024; Willetts 2022).

A move to individual filing would, of course, introduce new complexities to the tax code. Income-splitting, or high-income spouses transferring income to low-income spouses to avoid higher rates, is a particular concern (McMahon 2011). The revolution in information technology and third-party reporting over the past decade could reduce some administrative concerns, and tailored changes to reporting standards could reduce others. However, it may also be beneficial to women’s economic security if individual filing restores a tax preference for genuinely transferring legal ownership of assets and rights to income to a lower-earning spouse. Recall that the major backers of the introduction of joint filing for married couples were rich men in noncommunity property states who wanted the tax benefits of marital income splitting without the inconvenience of having to cede an ownership interest in their income to their wives (Kornhauser 1993). Moving away from taxation based on theoretical income pooling and toward a system where the tax benefits of income splitting can only be accomplished by granting genuine dominion and control over assets and income to the lower-earning spouse could increase women’s economic security and decision-making power within their marriages.

As Stephanie McMahon (2011) points out, the tax code privileges married couples in many ways, and a move to individual filing would require rethinking rules around deductions, property ownership, child credits, and more. But switching to individual filing presents a unique opportunity to change the way we structure the tax code and make it simpler, more functional, and more equitable overall, bringing the US tax code more in line with that of peer countries.

Conclusion

Since its adoption in 1948, the joint filing regime has had profound effects on the taxation of both married and single people. Initially designed to help wealthy married men pay lower taxes, joint filing has contributed to a tax code that is riddled with inequities for the married and unmarried alike and is justified by a series of flawed assumptions around resource pooling that have become less and less true over time. By taxing married couples together, the government penalizes egalitarian marriages, rewards sole-breadwinner households, and levies higher taxes on “secondary earners,” penalizing women’s labor force participation. Even married couples who receive a tax break from joint filing pay a price: Discouraging women’s labor force participation and earnings disempowers them both within their marriages and in the labor market and leads to persistent reductions in income and wealth over their lifetimes. Whether they know it or not, the majority of married couples face the effects of joint filing—not only on their tax bill but on their decisions about work, finances, and power.

A tax code built on the business interests of wealthy men will never be genuinely fair, and truly supporting women and modern families goes beyond narrow debates around marriage penalty relief. Ending joint filing would be a major step toward thinking bigger and building a simpler, more equal, and more progressive tax code that helps women thrive.

Footnotes

- The “economies of scale” argument would support a regime with higher taxes on married couples than on two individuals with the same combined income, so it falls apart when marriage instead provides a bonus. ↩︎

- The TPC Marriage Calculator uses tax parameters from 2021, excluding temporary provisions enacted to support families during the COVID-19 pandemic (most notably, for our purposes, the additional Child Tax Credit, which was in effect in 2021 but later expired). These examples reflect changes made under the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), including provisions set to expire at the end of 2025, but do not reflect inflation adjustments since 2021 to the thresholds for tax brackets or other parameters. Thus these figures are slightly different from what would result using 2025 parameters, but the basic results are the same. ↩︎

- Excluding state and local income tax and payroll taxes. ↩︎

- Although this example demonstrates the progressivity of the individual income tax, as Dan’s average effective tax rate is higher than Christine’s when they are unmarried, the tax code remains riddled with regressivity. The vast majority of state and local tax systems are regressive, with the lowest-income quintile of taxpayers, on average, paying a 60 percent higher state and local tax rate than the top 1 percent. This is largely due to a heavy reliance on sales and excise taxes, which unequally burden low-income taxpayers (ITEP 2024). ↩︎

- The TCJA introduced other marriage penalties, however. The law introduced a $10,000 cap on the deduction for state and local taxes (SALT) that is the same for individual filers and married couples filing jointly but is reduced to $5,000 on married-filing-separately returns. For high-income taxpayers with high state and local tax bills, this penalty can be significant. ↩︎

- The Head of Household filing status has both a larger standard deduction and larger tax brackets than the single filing status, recognizing the extra costs of living for individuals with dependents. ↩︎

- This is the same amount of federal tax that Dan and Christine, the couple with an uneven income split, would pay if they had a child. ↩︎

- The OTA found a significant second earner bonus for families earning less than $15,000. This is likely because any of these second earners with children would earn their first dollars in the phase-in period for the Child Tax Credit, and possibly for the Earned Income Tax Credit (TPC 2025; CBPP 2023). ↩︎

- The analysis uses 2015 law, which was changed in some important ways by the 2017 TCJA, but the basic trends still hold true. ↩︎

- The OTA assumed that the higher-earning spouse would file as Head of Household and claim all of the child-related benefits. If these benefits were transferred to the lower-earning spouse, especially the Earned Income Tax Credit, the lowest-income newly working spouses would fare even better under individual filing, often facing negative marginal tax rates on their first dollar of income. Also, these figures only account for federal income tax and thus understate the true marginal tax rate on labor income faced by many second earners once payroll taxes and state and local taxes are taken into account. ↩︎

- These data only cover heterosexual marriages, and while there is evidence that same-sex couples tend to have more egalitarian marriages (Machado and Jaspers 2023), members of same-sex couples may still face a second earner penalty. ↩︎

- The labor market effects of second earner penalties are not confined to women in heterosexual marriages, although that is the largest population of second earners. Elliott Isaac (2025) studies same-sex couples, for whom the legalization of same-sex marriage led to a sudden switch to joint taxation, and finds that joint taxation decreased labor force participation for second earners generally, with larger effects for female second earners. ↩︎

- Adjusted for family size. ↩︎

References

Alm, James, J. Sebastian Leguizamon, and Susane Leguizamon. 2023. “Race, Ethnicity, and Taxation of the Family: The Many Shades of the Marriage Penalty/Bonus.” National Tax Journal 76, no. 3 (September). https://journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.1086/724934.

Almeida, Beth, and Isabela Salas-Betch. 2023. “Fact Sheet: The State of Women in the Labor Market in 2023.” Center for American Progress, February 6, 2023. https://americanprogress.org/article/fact-sheet-the-state-of-women-in-the-labor-market-in-2023.

Apps, Patricia, and Ray Rees. 2018. “Optimal Family Taxation and Income Inequality.” International Tax and Public Finance 25: 1093–1128. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10797-018-9492-5.

Aughinbaugh, Alison, and Donna S. Rothstein. 2024. Patterns of Marriage and Divorce from Ages 15 to 55: Evidence from the NLSY79. Washington, DC: Bureau of Labor Statistics Monthly Labor Review. https://bls.gov/opub/mlr/2024/article/patterns-of-marriage-and-divorce-from-ages-15-to-55-evidence-from-the-nlsy79.htm.

Barham, Vicky, Rose Anne Devlin, and Jie Yang. 2009. “A Theory of Rational Marriage and Divorce.” European Economic Review 53, no. 1 (January): 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2008.02.002.

Beck, Richard C.E. 1990. “The Innocent Spouse Problem: Joint and Several Liability for Income Taxes Should Be Repealed.” Vanderbilt Law Review 43, no 2, article 2. https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2508&context=vlr.

Bick, Alexander, and Nicola Fuchs-Schündeln. 2017. “Quantifying the Disincentive Effects of Joint Taxation on Married Women’s Labor Supply.” American Economic Review: Papers & Proceedings 107, no. 5: 100–4. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.p20171063.

_____ 2018. “Taxation and Labour Supply of Married Couples across Countries: A Macroeconomic Analysis.” The Review of Economic Studies 85, no. 3 (July): 1543–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdx057.

Bierbrauer, Felix J., Pierre C. Boyer, Andreas Peichl, and Daniel Weishaar. 2023. “The Taxation of Couples.” CESifo Working Paper no. 10414. Munich: CESifo. https://ifo.de/en/cesifo/publications/2023/working-paper/taxation-couples.

Bittker, Boris I. 1974. “Federal Income Taxation and the Family.” Stanford Law Review 27. https://openyls.law.yale.edu/bitstream/handle/20.500.13051/1591/Federal_Income_Taxation_and_the_Family.pdf?sequence=2.

Brown, Dorothy. 2021. The Whiteness of Wealth. New York: Penguin Random House. https://penguinrandomhouse.com/books/591671/the-whiteness-of-wealth-by-dorothy-a-brown.

Brown, Patrick T. 2024. “It’s Time for a Bonus, Baby.” American Compass, August 27, 2024. https://americancompass.org/its-time-for-a-bonus-baby.

Budig, Michelle J. 2014. The Fatherhood Bonus and The Motherhood Penalty: Parenthood and the Gender Gap in Pay. Washington, DC: Third Way. https://thirdway.org/report/the-fatherhood-bonus-and-the-motherhood-penalty-parenthood-and-the-gender-gap-in-pay.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP). 2023. “Policy Basics: The Earned Income Tax Credit.” Research. Last updated April 28, 2023. https://cbpp.org/research/policy-basics-the-earned-income-tax-credit.

Cohen, Rachel. 2024. “Could Tweaks to the Tax Code Lead to More Marriages—and More Kids?” Vox, November 26, 2024, sec. Policy. https://vox.com/policy/387818/could-tweaks-to-the-tax-code-lead-to-more-marriages-and-more-kids.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO). 1997. For Better or for Worse: Marriage and the Federal Income Tax. Washington, DC: CBO. https://cbo.gov/sites/default/files/105th-congress-1997-1998/reports/marriage.pdf.

Costello, Rachel, Portia DeFilippes, Robin Fisher, Ben Klemens, and Emily Y. Lin. 2024. “Marriage Penalties and Bonuses by Race and Ethnicity: An Application of Race and Ethnicity Imputation.” Office of Tax Analysis (OTA) Working Paper no. 124. Washington, DC: OTA. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/WP-124.pdf.

Cunha, Darlena. 2016. “The Divorce Gap.” The Atlantic, April 28, 2016, sec. Business. https://theatlantic.com/business/archive/2016/04/the-divorce-gap/480333.

deCourcy, Katherine, and Elise Gould. 2023. “Gender Pay Gap Hits Historic Low in 2024—but Remains Too Large.” Working Economics (blog). Economic Policy Institute. March 25, 2025. https://epi.org/blog/gender-pay-gap-2024.

DiVito, Emily, and Matt Hughes. 2023. “The IRS Is Piloting a Direct File System. The TurboTax Settlement Shows We Need It.” Roosevelt Institute (blog). May 17, 2023. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/blog/the-irs-is-piloting-a-direct-file-system-the-turbotax-settlement-shows-we-need-it.

DiVito, Emily. 2024. “The TCJA Is Making Our Tax System—and Tax Season—More Burdensome.” Roosevelt Institute (blog). February 5, 2024. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/blog/tcja-is-making-our-tax-system-and-tax-season-more-burdensome.

Dutta-Gupta, Indivar. 2025. Direct Spending on Care Work: Thinking Beyond the Tax Code for Caregiving Infrastructure. New York: Roosevelt Institute. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/direct-spending-on-care.

Eissa, Nada, and Hilary Williamson Hoynes. 2004. “Taxes and the Labor Market Participation of Married Couples: The Earned Income Tax Credit.” Journal of Public Economics 88, no. 9–10 (August): 1931–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2003.09.005.

Entmacher, Joan, and Amy Matsui. 2013. “Addressing the Challenges Women Face in Retirement: Improving Social Security, Pensions, and SSI.” Marshall Law Review 46, no. 3, article 4. https://repository.law.uic.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1216&context=lawreview.

Fletcher, Jen. 2021. “Tax Tips for Survivors of Domestic Violence.” Get It Back Campaign, December 23, 2021. https://taxoutreach.org/blog/tax-tips-for-survivors-of-domestic-violence.

Foged, Mette. 2016. “Family Migration and Relative Earnings Potentials.” Labour Economics 42: 87–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2016.08.004.

Frimmel, Wolfgang, Martin Halla, and Rudolf Winter-Ebmer. 2014. “Can Pro-Marriage Policies Work? An Analysis of Marginal Marriages.” Demography 51, no. 4: 1357–79. https://read.dukeupress.edu/demography/article-abstract/51/4/1357/169506/Can-Pro-Marriage-Policies-Work-An-Analysis-of?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

Fry, Richard, Carolina Aragão, Kiley Hurst, and Kim Parker. 2023. In a Growing Share of U.S. Marriages, Husbands and Wives Earn About the Same. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/04/13/in-a-growing-share-of-u-s-marriages-husbands-and-wives-earn-about-the-same.

Gelles, Richard J. 1976. “Abused Wives: Why Do They Stay.” Journal of Marriage and Family 38, no. 4 (November): 659–68. https://doi.org/10.2307/350685.

Gerzema, John. 2023. “America This Week Wage 187.” The Harris Poll, September 27, 2023. https://theharrispoll.com/briefs/america-this-week-wave-187.

Goldin, Claudia. 2021. Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691201788/career-and-family?srsltid=AfmBOoqF8egCrzlmg5bGxv2XEH9dcDqkdM-cUMFgtSAUvRhRMm0N2AAr.

Goolsbee, Austan. 2006. “The ‘Simple Return’: Reducing America’s Tax Burden Through Return-Free Filing.” Hamilton Project Discussion Paper 2006-004. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. https://brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/200607goolsbee.pdf.

Government Accountability Office (GAO). 2012. Retirement Security: Women Still Face Challenges. GAO-12-699. Washington, DC: GAO. https://gao.gov/products/gao-12-699.

Greenwood, Jeremy, Nezih Guner, Georgi Kocharkov, and Cezar Santos. “Marry Your Like: Assortative Mating and Income Inequality.” American Economic Review 104, no. 5 (May): 348–53. https://aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/aer.104.5.348.

Grigoryeva, Angelina. 2017. “Own Gender, Sibling’s Gender, Parent’s Gender: The Division of Elderly Parent Care among Adult Children.” American Sociological Review 82, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416686521.

Hawkins, Daniel N., and Alan Booth. 2005. “Unhappily Ever After: Effects of Long-Term, Low-Quality Marriages on Well-Being.” Social Forces 84, no. 1 (September): 451–71. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2005.0103.

Hill, Jonquilyn. 2024. “Why the Marriage Rate Is Falling Faster for Some.” Vox, February 14, 2024. https://vox.com/24072078/marriage-america-race-policy-history.

Holtzblatt, Janet, Swati Joshi, Nora R. Cahill, and William Gale. 2023. “Racial Disparities in the Income Tax Treatment of Marriage.” NBER Working Paper no. 31805. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. https://nber.org/papers/w31805.

Horowitz, Julia Menasce, Nikki Graf, and Gretchen Livingston. 2019. Marriage and Cohabitation in the US. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/11/06/why-people-get-married-or-move-in-with-a-partner.

Infanti, Anthony C. 2010. “Decentralizing Family: An Inclusive Proposal for Individual Tax Filing in the United States.” Utah Law Review 605. https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles/336.

Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR). 2024. State by State, Mothers Are Paid Much Less than Fathers. Washington, DC: IWPR. https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/Mothers-Equal-Pay-Fact-Sheet-2024.pdf.

_____ 2025. Women at Work Five Years Since the Start of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Any Progress? Washington, DC: IWPR. https://iwpr.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Women-at-Work-Five-Years-Since-the-Start-of-the-COVID-19-Pandemic-fact-sheet_March-2025.pdf.

Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). 2024. Who Pays? A Distributional Analysis of the Tax Systems in All 50 States. Washington, DC: ITEP. https://itep.org/whopays-7th-edition.

Internal Revenue Service (IRS). 2022. Individual Income Tax Returns Complete Report. Washington, DC: IRS. https://irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p1304.pdf#page=24.

_____ 2024. “Innocent Spouse Relief.” Last updated November 8, 2024. https://irs.gov/individuals/innocent-spouse-relief.

Isaac, Elliott. 2023. “Suddenly Married: Joint Taxation and the Labor Supply of Same-Sex Married Couples After United States v. Windsor.” Journal of Human Resources 60, no. 3 (May). https://jhr.uwpress.org/content/60/1/1.

Johnson, Laura, Yafan Chen, Amanda Stylianou, and Alexandra Arnold. 2022. “Examining the Impact of Economic Abuse on Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence: A Scoping Review.” BMC Public Health. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9121607.

Johnson, Richard W., Karen E. Smith, and Barbara Butrica. 2023. “Unpaid Family Care Continues to Suppress Women’s Earnings.” Urban Wire (blog). Urban Institute. June 9, 2023. https://urban.org/urban-wire/unpaid-family-care-continues-suppress-womens-earnings.

Kasprak, Nick. 2013. “Joint Filing in the Tax Code.” Tax Foundation (blog). June 26, 2013. https://taxfoundation.org/blog/joint-filing-tax-code.

Kearney, Melissa. 2023a. “A Driver of Inequality That Not Enough People Are Talking About.” The Atlantic, September 18, 2023, sec. Ideas. https://theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2023/09/marriage-two-parent-households-socioeconomic-consequences/675333.

_____ 2023b. The Two-Parent Privilege: How Americans Stopped Getting Married and Started Falling Behind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/T/bo205550079.html.

Kitchener, Caroline. 2025. “White House Assesses Ways to Persuade Women to Have More Children.” New York Times, April 21, 2025, sec. Politics. https://nytimes.com/2025/04/21/us/politics/trump-birthrate-proposals.html.

Kornhauser, Marjorie E. 1993. “Love, Money, and the IRS: Family, Income-Sharing, and the Joint Income Tax Return.” Hastings Law Journal 45: 63–111. https://repository.uclawsf.edu/hastings_law_journal/vol45/iss1/3.

_____ 1999. “Deconstructing the Taxable Unit: Intrahousehold Allocations and the Dilemma of the Joint Return.” NYLS Journal of Human Rights 16, no. 1, article 8. https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1386&context=journal_of_human_rights.

LaLumia, Sara. 2006. “The Effects of Joint Taxation of Married Couples on Labor Supply and Non-wage Income.” College of William and Mary Department of Economics Working Paper no. 28. Williamsburg, VA: College of William and Mary. https://economics.wm.edu/wp/cwm_wp28.pdf.

_____ 2008. “The Effects of Joint Taxation of Married Couples on Labor Supply and Non-wage Income.” Journal of Public Economics 92, no. 7 (July): 1698–1719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.01.009.

Leopold, Thomas. 2018. “Gender Differences in the Consequences of Divorce: A Study of Multiple Outcomes.” Demography 55, no. 3: 769–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0667-6.

Lersch, Philipp, Marita Jacob, and Karsten Hank. 2017. “Parenthood, Gender, and Personal Wealth.” European Sociological Review 33, no. 3 (June): 410–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcx046.

Liebman, Jeffrey, and Daniel Ramsey. 2019. “Independent Taxation, Horizontal Equity, and Return-Free Filing.” Tax Policy and the Economy 33. https://journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/703230.

Livingston, Gretchen, and Anna Brown. 2017. Intermarriage in the U.S. 50 Years After Loving v. Virginia. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://pewresearch.org/social-trends/2017/05/18/intermarriage-in-the-u-s-50-years-after-loving-v-virginia.

Machado, Weverthon, and Eva Jaspers. 2023. “Money, Birth, Gender: Explaining Unequal Earnings Trajectories following Parenthood.” Sociological Science 10: 429–53. https://sociologicalscience.com/download/vol_10/may/SocSci_v10_429to453.pdf.

Madowitz, Michael, Alex Rowell, and Katie Hamm. 2016. Calculating the Hidden Cost of Interrupting a Career for Child Care. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. https://americanprogress.org/article/calculating-the-hidden-cost-of-interrupting-a-career-for-child-care.

Make Marriage Great Again Act of 2025, H.R. Res. 320, 119th Cong. (2025). https://congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/320/text.

Matsui, Amy. 2022. Improving Retirement Security and Access to Mental Health Benefits: U.S. House of Representatives, Committee on Education and Labor Subcommittee on Health, Employment, Labor, and Pensions, 117th Cong. (2022) (statement of Amy Matsui, Director of Income Security, National Women’s Law Center). https://docs.house.gov/meetings/ED/ED02/20220301/114437/HHRG-117-ED02-Wstate-MatsuiA-20220301.pdf.

McCaffery, Edward J. 1997. Taxing Women. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/T/bo3637040.html.

McClelland, Robert, and Shannon Mok. 2012. “A Review of Recent Research on Labor Supply Elasticities.” Congressional Budget Office Working Paper no. 2012-12. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office. https://cbo.gov/sites/default/files/112th-congress-2011-2012/workingpaper/10-25-2012-recentresearchonlaborsupplyelasticities.pdf.

McMahon, Stephanie. 2011. “To Have and to Hold: What Does Love (of Money) Have to Do with Joint Tax Filing.” Nevada Law Journal. https://scholarship.law.uc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1203&context=fac_pubs.

Miller, Claire Cain. 2014. “The Divorce Surge Is Over, but the Myth Lives On.” New York Times, December 2, 2014, sec. The Upshot. https://nytimes.com/2014/12/02/upshot/the-divorce-surge-is-over-but-the-myth-lives-on.html.

Mitchell, Alison. 2000. “The 2000 Campaign: The Strategies; Bush Returning Tax-Cut Plan to Center Stage.” New York Times, October 2, 2000. https://nytimes.com/2000/10/02/us/the-2000-campaign-the-strategies-bush-returning-tax-cut-plan-to-center-stage.html.

Moran, Beverly. 2024. When Tax Policy Discriminates: The TCJA’s Impact on Black Taxpayers. New York: Roosevelt Institute. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/when-tax-policy-discriminates.

Muresianu, Alex. 2021. “Return-Free Filing: A Better Fit for a Better Tax Code.” Tax Foundation (blog). August 5, 2021. https://taxfoundation.org/blog/return-free-filing.

Nolan, Matt. 2013. “Tax distortions and Burden.” Infometrics, May 16, 2013. https://infometrics.co.nz/article/2013-05-tax-distortions-and-burden.

Office of Tax Analysis (OTA). 2015. The Income Tax Treatment of Married Couples. Washington, DC: OTA. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/Two-Earner-Penalty-and-Marginal-Tax-Rates.pdf.

Olson, Sarah. 2005. “Marriage Promotion, Reproductive Injustice, and the War Against Poor Women of Color.” Dollars & Sense, January 2005. https://dollarsandsense.org/archives/2005/0105olson.html.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2024. Taxing Wages 2024: Tax and Gender through the Lens of the Second Earner. Paris: OECD. https://oecd.org/en/publications/taxing-wages-2024_dbcbac85-en/full-report/component-2.html#section-d1e197-deccadfdb1.

Pedulla, David S., and Sarah Thébaud. 2015. “Can We Finish the Revolution? Gender, Work-Family Ideals, and Institutional Constraint.” American Sociological Review 80, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414564008.

Penn Wharton Budget Model. 2025. “Change in American Families: Favoring Cohabitation Over Marriage.” Penn Wharton Budget Model, February 19, 2025. https://budgetmodel.wharton.upenn.edu/issues/2025/2/19/change-in-american-families-favoring-cohabitation-over-marriage.

Pepin, Joanna R. 2022. “A Visualization of U.S. Couples’ Money Arrangements.” Socius. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231221138719.

Pilossoph, Laura, and Shu Lin Wee. 2021. “Household Search and the Marital Wage Premium.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 13, no. 4 (October): 55–109. https://aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/mac.20180092.

Ponder, Meghen. 2025. “Filing Taxes for Married Couples: Benefits and Tips.” TaxAct, February 25, 2025. https://blog.taxact.com/filing-taxes-married-couples-benefits.

Popkin, William D. 1975. “Household Services and Child Care in the Income Tax and Social Security Laws.” Indiana Law Journal 50: no. 2, article 3. https://repository.law.indiana.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3060&context=ilj.

Reeves, Richard V., and Christopher Pulliam. 2020. “Middle Class Marriage Is Declining, and Likely Deepening Inequality.” Brookings Institution, March 11, 2020. https://brookings.edu/articles/middle-class-marriage-is-declining-and-likely-deepening-inequality.

Republican Members of the House of Representatives. 1994. “The Republican ‘Contract with America.’” US House of Representatives. https://global.oup.com/us/companion.websites/9780195385168/resources/chapter6/contract/america.pdf.

Ribar, David C. 2004. “What Do Social Scientists Know About the Benefits of Marriage? A Review of Quantitative Methodologies.” IZA Discussion Paper no. 998. Bonn, Germany: IZA. https://docs.iza.org/dp998.pdf.

Richards, Kitty. 2017. “An Expressive Theory of Tax.” Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy 27, no. 2, article 2. https://lawschool.cornell.edu/research/JLPP/upload/Kitty-final.pdf.

Robertson, Cassandra, and Samarth Gupta. 2022. Improving Public Programs for Low-Income Tax Filers. Washington, DC: New America. https://newamerica.org/new-practice-lab/reports/improving-public-assistance-for-low-income-tax-filers.

Saez, Emmanuel, Joel Slemrod, and Seth H. Giertz. 2012. “The Elasticity of Taxable Income with Respect to Marginal Tax Rates: A Critical Review.” Journal of Economic Literature 50, no. 1 (March): 3–50. https://aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jel.50.1.3.

Salas-Betch, Isabela. 2024. The Economic Status of Single Mothers. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. https://americanprogress.org/article/the-economic-status-of-single-mothers.

Schanzenbach, Diane Whitmore, and Michael R. Strain. 2020. “Employment Effects of the Earned Income Tax Credit: Taking the Long View.” IZA Discussion Paper no. 13818. Bonn, Germany: IZA. https://docs.iza.org/dp13818.pdf.

Selin, Håkan. 2013. “The Rise in Female Employment and the Role of Tax Incentives: An Empirical Analysis of the Swedish Individual Tax Reform of 1971.” International Tax and Public Finance 21: 894–922. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10797-013-9283-y.

Tax Policy Center (TPC). 2021. “Marriage Calculator.” Accessed May 12, 2025. https://tpc-marriage-calculator.urban.org.

_____ 2024. “What Are Marriage Penalties and Bonuses?” The Tax Policy Briefing Book. Last updated January 2024. https://taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-are-marriage-penalties-and-bonuses.

_____ 2025. “What Is the Child Tax Credit?” The Tax Policy Briefing Book. Last updated April 2025. https://taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-child-tax-credit.

Whalen, J. R. 2023. “Why Some Married Couples File Taxes Separately.” Your Money Briefing (podcast). Wall Street Journal, March 7, 2023. Audio. https://wsj.com/podcasts/your-money-matters/why-some-married-couples-file-taxes-separately/522c5d21-e805-4a1b-a509-0976deec2f4e.

Willetts, Jo. 2022. “What Is Innocent Spouse Relief and How Do I Qualify?” Jackson Hewitt Tax Services, July 12, 2022. https://jacksonhewitt.com/tax-help/tax-tips-topics/back-taxes/what-is-innocent-spouse-relief-and-do-i-qualify.

Suggested Citation

Richards, Kitty, and Noa Rosinplotz. 2025. “It’s Time to End Joint Tax Filing.” Roosevelt Institute, June 5, 2025.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Elizabeth Pancotti and Suzanne Kahn for their help and insight on this paper, and Katherine De Chant and Aastha Uprety for excellent editorial input. The authors especially thank Amy Matsui for her valuable feedback. Any errors, omissions, or other inaccuracies are the authors’ alone.