The Predistribution Solution

December 17, 2025

By Sunny Malhotra and Steven K. Vogel

Introduction

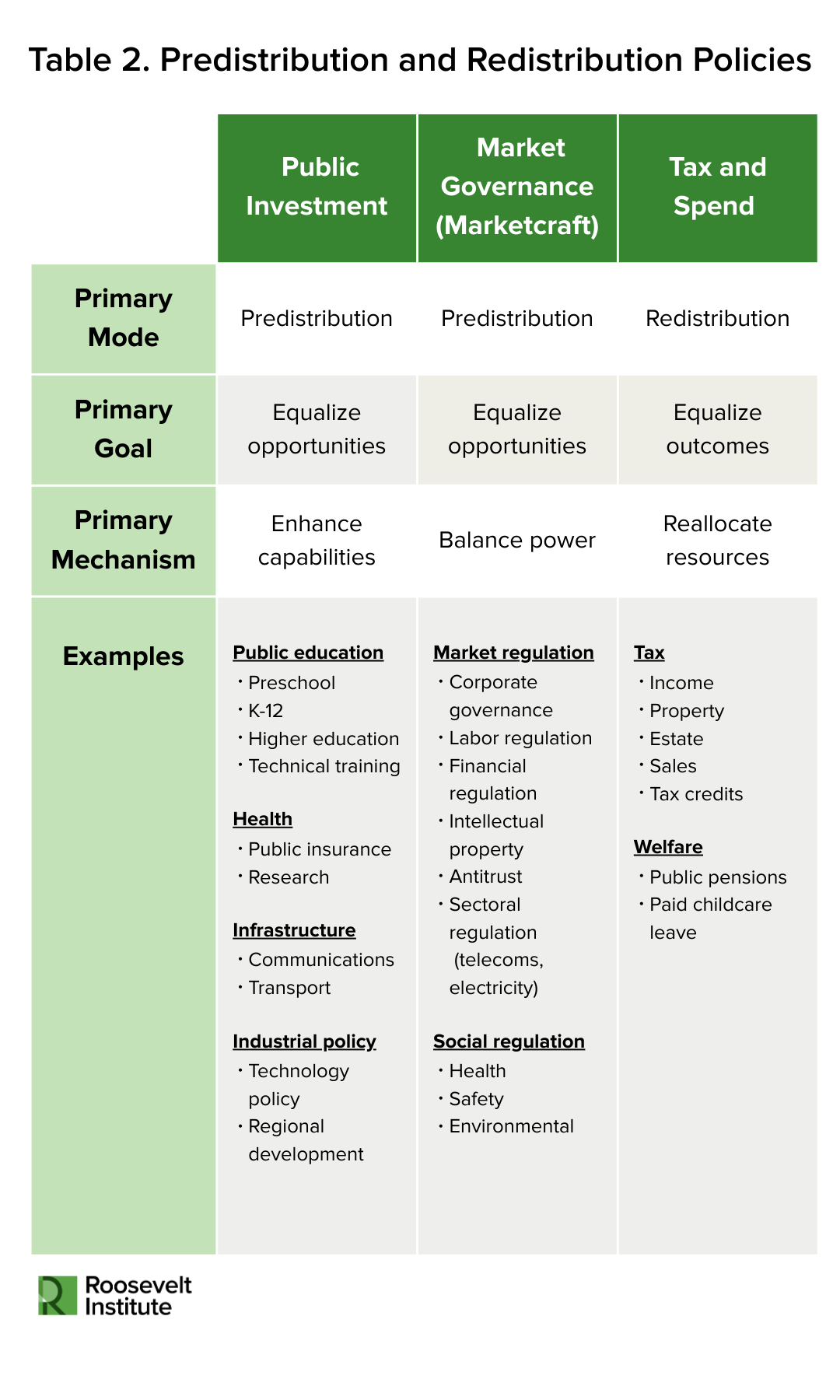

This policy brief analyzes the American political economy past and present through the lens of “predistribution.” Predistribution policies seek to achieve greater equality in opportunities, resources, and power, whereas redistribution policies take from some and give to others (Hacker 2011). Predistribution policies include public investments in education to foster substantive equality of opportunity and market regulations to balance power in the economy. Redistribution policies include progressive taxation and welfare spending to achieve greater equality of outcomes, such as income and wealth. We readily acknowledge that the two types of policy can blur in practice, yet the conceptual distinction is useful nonetheless.

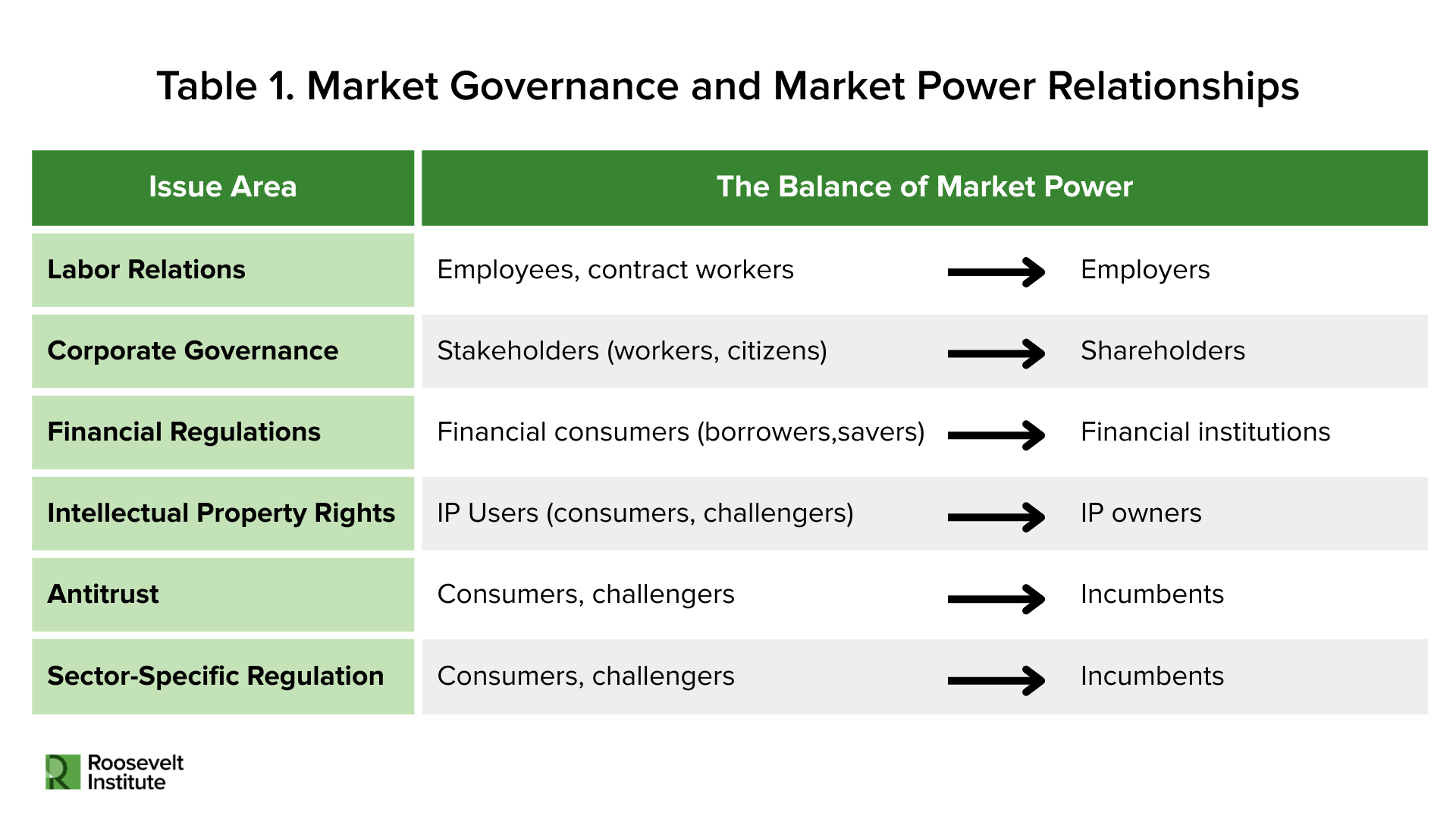

We contend that the predistribution policy agenda provides the most compelling alternative to neoliberalism and plutocratic populism, both in theory and in practice. The term “neoliberal” can be used to refer to everything from an ideology to a stage of capitalism to a basket of policies (Rodgers 2018). In the realm of theory, neoliberals tend to hold the free market as an ideal. They view markets as arenas of freedom and government actions as constraints on individual freedom and impediments to market efficiency. Therefore, they seek to limit government “intervention” in markets (Vogel 2018). In practice, however, US neoliberalism since the 1970s has not reduced government regulation but rather shifted market governance in favor of those with wealth and power—that is, from the left to the right in Table 1 (Vogel 2021). Plutocracy refers to government by and for the rich, while populism denotes movements that mobilize mass support by claiming to represent the common people against the elite (Hacker and Pierson 2020). Hence, plutocratic populism constitutes a mutant form of neoliberalism more than a break from it in that it still seeks to redistribute power and wealth upward (Callison and Manfredi 2019). Therefore, the antidote to both neoliberalism and plutocratic populism would be to reverse the arrows in the other direction—and that is the essence of the predistribution solution.

At the level of theory, the predistribution framework specifies how capitalism can go wrong and what we can do about it. This brief stakes out a position distinct from those who view increasing inequality as an inevitable feature of capitalism and those who view redistribution via taxes and welfare spending as a satisfactory remedy. It stresses that the propensity for economic inequality is rooted in institutions and policies.

Let us be clear. We are not proposing that predistribution policies should displace redistributive policies. We view the two sets of policies more as complements than substitutes. However, we believe that predistribution should be given priority in three specific senses. First, the long-term goal should be to create an equal society, not simply to compensate people for an unequal one. Second, policymakers should proceed with predistribution policies as far as possible and reduce redistribution to the extent that predistribution obviates the need for it. And third, researchers should evaluate policies through the lens of predistribution, examining opportunities, social status, and power as well as economic outcomes.

In practice, our current economic system can only be reformed effectively by channeling public investment to enhance human capabilities for all and by transforming the market governance that defines the power relationships in the economy. In this brief, we focus on the latter, the market regulation or “marketcraft” bucket of policies to rebalance power in the economy (Stiglitz et al. 2015; Stiglitz 2016; Vogel 2018). Specifically, that means:

- Reform labor laws and regulations to strengthen the bargaining power of workers

- Revise corporate governance to give more voice to a broad range of stakeholders, especially workers

- Strengthen financial regulation to constrain rent-seeking by the financial sector and promote value creation for investors and consumers

- Selectively reduce intellectual property protection to lower producer rents, enhance consumer value, and foster more collaborative models of innovation

- Tighten antitrust enforcement to constrain the power of Big Tech firms, empower challenger firms, foster innovation, and balance market and political power more broadly

- Reform market governance specific to certain industries—such as electricity, telecommunications, and airlines—to deliver more value for consumers

This may seem like an odd moment to present an idealistic vision—but this is precisely what we need at this juncture in history. America’s failure to predistribute sufficiently over the past 50 years has denied many Americans the dignity of good jobs with fair pay and a reasonable opportunity to improve their material welfare. This has undermined working-class Americans’ faith in government. In this brief we present a predistribution framework with two goals in mind: (1) to propose concrete policy options, including some measures that may be viable in the short to medium term, and (2) to provide a vision to rebalance economic, social, and political power over the longer run. We need to chart an ambitious vision for a better future—and then we can confront the daunting challenge of how to get from here to there.

What Is Predistribution?

Jacob S. Hacker (2011) popularized the concept of “predistribution,” and the British Labour Party briefly embraced it as a pillar of its program in 2012.1 One way to think about predistribution is that it determines a person’s income before taxes and transfers, while redistribution takes this income as given and then reallocates resources. Olivier Blanchard and Dani Rodrik (2021) conceive of this distinction in terms of policies that target three different stages of production: preproduction (such as public education), production (such as market regulation), and postproduction (such as social transfers). The first and second are the realms of predistribution, while the third constitutes redistribution.

With respect to goals, predistribution is more concerned with equalizing opportunities, whereas redistribution is more oriented toward equality of outcome. With respect to means, predistribution policies strive to enhance capabilities and balance power, whereas redistribution policies reallocate resources (Table 2).

Yet real-world policies do not sort neatly into pure predistribution and redistribution boxes. A given policy can have both predistributive and redistributive effects (O’Neill 2020). For example, if the government is spending more on education for the poor than for the rich, then it is enhancing the productive capacities of those with fewer resources (predistribution) but also reallocating resources with value (redistribution). If the government revises labor regulations to give workers more power relative to employers (predistribution), this is likely to boost wages as well (redistribution). Progressive taxation shifts resources from the wealthy to the poor (redistribution), but it can also give lower-income workers more leverage to bargain with their employers (predistribution). And childcare subsidies for lower-income families directly transfer funds (redistribution) but also give parents greater ability to upgrade their skills or get a job (predistribution).

Despite these blurred lines, the conceptual distinction is valuable because it allows us to assess the redistributive and predistributive characteristics of these policies, and this can be usefully applied to evaluate policy options. For example, policymakers might favor those predistributive policies with greater redistributive effects (such as labor reforms, noted above) or those redistributive policies with greater predistributive benefits (such as childcare subsidies). The conceptual distinction highlights the difference between policies that favor equality of opportunity versus equality of outcome, investment versus compensation, long-term effects versus short-term benefits, and, perhaps most importantly, balancing power versus equalizing returns.

Table 2 provides some examples of predistributive and redistributive policies, their goals, and the mechanisms of achieving those goals. It divides policies into four main buckets: public investments and market governance that are primarily predistributive, and taxation and welfare spending that are primarily redistributive. Industrial policy is primarily predistributive in that it shapes the industrial composition and manufacturing capabilities of particular firms, sectors, or geographical regions; but it is also redistributive in that it reallocates resources across these firms, sectors, and regions (Tucker et al. 2024).

Furthermore, while this brief focuses primarily on the implications of predistributive policies for economic equality and opportunity, the concept of a predistribution agenda applies to a wide range of substantive issues and policy goals. For example, while climate policy is beyond the scope of this brief, a predistributive lens would be useful in setting priorities and designing policies in that realm. It would focus attention on cultivating capabilities to lower carbon emissions, develop renewable energy sources, and to manage the energy transition in an equitable fashion. Relying on tax credits to address climate change raises concerns for equity and justice for disadvantaged communities, the communities most harmed by the fossil fuel economy and most at risk from climate change (Daly and Chi 2022).

Economists have usefully applied this distinction to separate out the sources of inequality empirically. Thomas Blanchet, Lucas Chancel, and Amory Gethin (2022) examine the United States and 26 European countries from 1980 to 2017 and find that predistribution and not redistribution explains why inequality has grown so much more in the United States than in Europe during this period. In fact, they find that the United States redistributes a greater share of national income to lower-income groups than any European country. They identify public investment in education and health and market regulation of finance and labor as predistribution policies that likely contribute to the difference, but they concede that their data does not allow them to disaggregate the effects among predistribution policies. Nonetheless, they conclude that the policy recommendation is clear: If predistribution influences inequality more than redistribution, then predistribution policies should be the priority remedy.

For practical purposes, the government should pursue both: redistributive policies such as a wealth tax that will reduce inequality the most quickly, and the predistribution policies that will address inequality at its roots and make for a more equitable society over the longer term.

As stressed above, we are not arguing against redistribution. In fact, certain redistributive policies have the potential to address economic inequality more quickly than predistribution policies. In particular, an aggressive wealth tax such as that advocated by Thomas Piketty (2014) and Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman (2019) would reduce inequalities of wealth more rapidly than a predistribution agenda, while also bestowing predistributive effects. In fact, a wealth tax could significantly shift the balance of power in the US economy and politics. As such, we view those redistributive policies that have strong predistributive effects as complements to the agenda laid out above, not substitutes. However, reliance on tax credits and other incremental “market-correcting” mechanisms is not sufficient to address the structural imbalances of power in our economy. For practical purposes, the government should pursue both: redistributive policies such as a wealth tax that will reduce inequality the most quickly, and the predistribution policies that will address inequality at its roots and make for a more equitable society over the longer term.

The Rise and Fall of Predistribution

In retrospect, the New Deal was a unique project of both predistribution and redistribution. On the predistribution front: It included major public investment in infrastructure via the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the federal Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), and the Works Progress Administration (WPA). It created jobs directly through the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). It supported rural incomes via the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). It bolstered worker power with the National Labor Relations Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act. It overhauled financial regulation with the Banking Act and the Securities Act in 1933. It had a more mixed record on antitrust, first embracing government-industry collaboration and industry self-regulation and later strengthening enforcement. The Robinson-Patman Act of 1936 expanded the scope of antitrust policy by making it illegal to charge different prices for the same product. Meanwhile, the New Deal also featured major redistributive policies, including more progressive income taxes, a wealth tax, relief for the poor, and the Social Security Act of 1935.

The postwar years of 1945–70 brought the “golden age” of Keynesian economics and the mixed economy. In hindsight, however, we can see that the US government emphasized redistribution more than predistribution. Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon expanded the redistributive welfare systems established under Franklin D. Roosevelt with reforms to Social Security. Meanwhile, New Deal predistribution policies were not so much dismantled as allowed to “drift” (Hacker 2005). In labor relations, for example, filibusters in the Senate stymied Democrats’ attempts to strengthen labor legislation, and this allowed employers to become more aggressive in their anti-union tactics. The golden age delivered strong economic growth, high social mobility, and lower economic inequality. This era’s economic agenda, combined with social movements such as the Civil Rights and Black Power movements, contributed to the reduction of racial income and wealth gaps (Mason 2023).

However, two oil shocks, stagflation, backlash against the Civil Rights Movement, and the perceived failures of the Jimmy Carter administration (1977–81) set the stage for the turn to neoliberal policies under President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. The architects of the Reagan revolution claimed to be curtailing the power of the state and reducing regulation of the economy, and thereby shifting authority from the government to the market. In practice, however, they deployed state authority and transformed regulation to shift power from workers to employers, from challengers to incumbents, from stakeholders to shareholders, from financial consumers to financial institutions, and from intellectual property users to owners (Vogel 2022). In this sense, neoliberal reform constituted upward (or reverse) predistribution, the opposite of a true predistribution agenda. As political scientist Wendy Brown (2006) puts it, neoliberal economic ideology and neoconservative political ideology are inextricably linked—both have symbiotically undermined democracy and re-rigged power to favor the dominant social class.

For example, Reagan deployed state power when he used executive authority to fire air traffic controllers who were on strike, thereby assaulting union power. He appointed more business-friendly representatives to the National Labor Relations Board and enacted rule changes that made it easier for companies to decertify unions and harder for unions to win elections. In antitrust policy, the Reagan administration embraced the Chicago School, which contended that monopolies tend to be fragile and competition robust because competitors were likely to challenge firms that attempt to charge monopoly prices over time. Moreover, Chicago School adherents believed the government might be incapable of devising an appropriate remedy or might be captured by political interests, so they were reluctant to prescribe government action even when a firm dominates a market or engages in anticompetitive practices (Posner 1979; Hovenkamp 2005). This shift in policy contributed to a boom in mergers in the 1980s. The administration also favored reforms that gave financial institutions greater liberty to take risks, such as the Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982, which liberalized savings and loan (S&L) associations’ use of funds, permitted adjustable-rate mortgage loans, and authorized money market deposit and “super” NOW accounts. Reagan-era policies also contributed to the shift toward the shareholder model of corporate governance, whereby firms maximize short-term returns for shareholders, often at the expense of wages and investments. For example, the Reagan administration reduced corporate income taxes, thereby providing more capital for the merger movement, and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) relaxed restrictions on corporate share buybacks (Vogel 2022). The Reagan administration also engaged in upward redistribution, cutting taxes and vowing to shrink the welfare state. Reagan and his allies deployed veiled racial references, or “dog whistles,” with the implication that benefits disproportionately benefit minorities, to justify cuts to welfare spending (Haney Lopez 2013).2

Yet Republicans were not the only ones who failed to predistribute. Bill Clinton administration (1993–2001) officials moderated plans for boosting public investment in the face of concerns over the budget deficit. They failed to pass health-care and labor reforms. They accelerated the financialization of the economy by permitting interstate banking in 1994, repealing the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999, and deciding not to regulate derivative financial instruments in 1998. They embraced globalization with the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1993 and prepared for China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (finalized under President George W. Bush in 2001). They dealt with the Japanese competitive challenge by favoring trade negotiations to reduce Japan’s barriers to US companies instead of protecting American producers or strengthening domestic capabilities with a vigorous industrial policy (Alden 2016; Lichtenstein 2018). The Clinton administration did not substantially boost redistribution either. Clinton campaigned on “ending welfare as we know it.” He ostensibly sought to end the cycle of dependence and to make work and responsibility the law of the land. In practice, he constrained spending on poverty eradication while expanding the carceral state with harsher sentencing and higher spending (Floyd et al. 2021).

The Barack Obama administration also failed to reboot a predistribution agenda. To its credit, it finally succeeded with a health-care reform bill that substantially expanded insurance coverage. Yet Obama had to compromise on key elements of the proposal, most notably withdrawing a plan to offer public options that would compete with private insurance companies. The administration moved cautiously on antitrust. The Federal Trade Commission took on Google in 2011 but ultimately judged that Google’s practices had benefited consumers and that any negative impact on competitors was incidental to that goal. The Council of Economic Advisers published a paper arguing for a more robust antitrust policy in 2016, the final year of Obama’s second term. Obama’s most fateful move, in terms of eroding support for his party among the working class, was to address the financial crisis of 2008 by bailing out Wall Street but not Main Street. The administration not only rescued the financial sector but refrained from nationalizing the banks (even temporarily) or punishing bank executives. Meanwhile, the government offered little support for middle-class citizens who lost their homes to foreclosure. Congress passed substantial financial reform in the form of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010, yet critics contend that concessions made during the legislative process, subsequent rulemaking and implementation, and amendments compromised the bill.

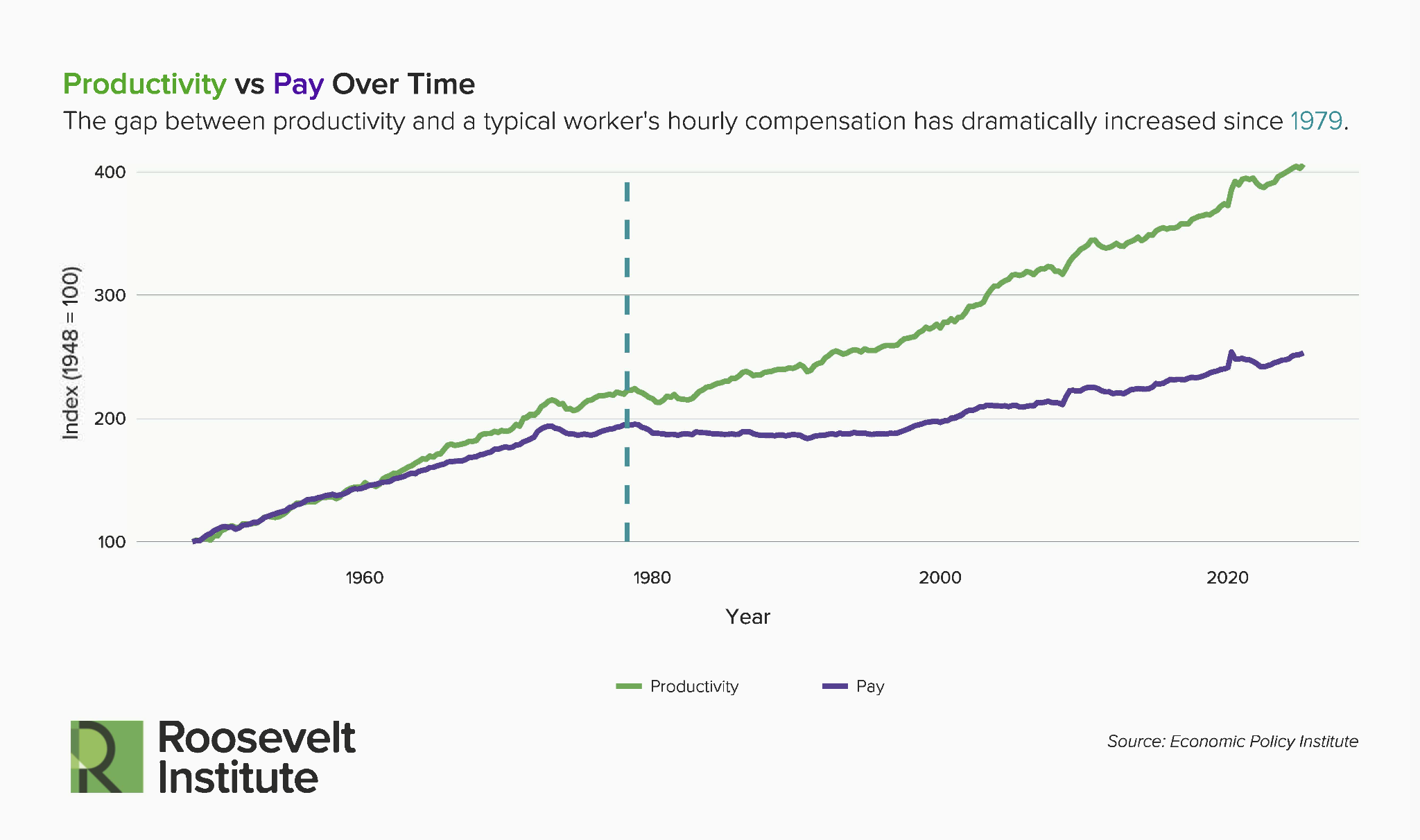

Medium-income workers have hardly benefited from increases in their own productivity or from strong GDP growth for about 50 years. Almost all of the benefits from greater productivity and higher growth have gone to the top.

The neoliberal turn had enormous distributional consequences. We can see this starkly in the gap between productivity growth and wage growth that first appeared in the 1970s and expanded thereafter (Figure 1 below). This gap has some rather staggering implications. It means that medium-income workers have hardly benefited from increases in their own productivity or from strong GDP growth for about 50 years. Almost all of the benefits from greater productivity and higher growth have gone to the top.

Figure 1

Equality of opportunity has also eroded, with sharp declines in social and geographical mobility. The share of children earning more than their parents has fallen from about 90 percent for the 1940 birth cohort to about 50 percent for the 1980s cohorts (Chetty et al. 2017). Both overall residential moves and interstate migration have declined dramatically since the 1980s (US Census Bureau 2024, Frost 2025). Where one is born and raised now exerts a stronger influence on adult outcomes, reinforcing economic and social inequality.

No wonder that middle-class Americans are angry! Many people feel that their political leaders have catered to those with power and wealth, while their own standard of living and prospects for upward mobility have eroded.3 They have lost faith in the government to address their needs.

Ilyana Kuziemko, Nicholas Longuet-Marx, and Suresh Naidu (2023) argue that the Democratic Party’s supply of predistribution policies declined after an inflection point in the 1970s, and that this helps to explain why the Democratic Party lost support from less-educated Americans. They find that Americans in general—and less-educated Americans in particular—support predistribution policies more than redistribution policies. They challenge conventional political economy models of one-dimensional policy preferences that assume that people only care about consumption and leisure. These models assume, for example, that people would prefer an equivalent fiscal transfer over a government job. The authors claim, in contrast, that Americans care more about their pre-tax-and-transfer income. They value social standing and status and employment quality, such as job autonomy and flexible hours.4

This brings us to a potential challenge to our case: Some might contend that the Joe Biden administration tried predistribution and it failed, both economically and politically. We concur that the Biden administration came closest to enacting a predistribution policy agenda since President Franklin D. Roosevelt, especially on the marketcraft side. Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan dramatically shifted the antitrust paradigm, taking on the Big Tech digital platform firms, challenging junk fees, and banning noncompete clauses. Biden took a much stronger pro-labor position than any president in recent history, strengthening labor regulation and publicly supporting strikes. Progressives took up key positions in the administration, including many who embraced elements of the predistribution agenda.

The Biden administration also deployed fiscal expansion with the American Rescue Plan to bring the US economy out of the COVID-19 crisis. The fiscal stimulus may have contributed to inflation, but it was necessary to restore growth and the administration was able to orchestrate a soft landing and bring down inflation over time. The United States fared better in this period than most other industrial nations. And the fiscal expansion contributed to a tighter labor market, thereby strengthening the bargaining power of workers and boosting wages. The administration also delivered massive investment in infrastructure via the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the CHIPS and Science Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act. This led to a marked increase in manufacturing investment as well as the creation of more good jobs. Yet the Biden administration was stymied in some of its most ambitious initiatives—such as the Inflation Reduction Act—by the thinness of its majority in Congress and resistance from Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia. The administration also encountered implementation hurdles, with policy not always reaching those in most need (Glickman and Dutta 2025).

Despite the substantial departure in the economic policy paradigm under Biden, many Americans did not experience tangible gains that they could attribute to specific policies. They were understandably fixated on inflation, and they did not give the administration credit for partial success in containing it. They also did not always understand the condition of the economy or whom to credit or blame for it. A May 2024 poll for the Guardian (Aratani 2024) found that 56 percent of those surveyed believed the economy was in recession even though it was not; 49 percent believed the S&P 500 stock market index was down for the year although it was up by 12 percent; and 49 percent believed that unemployment was at a 50-year high even though it was under 4 percent, near a 50-year low.

The predistribution agenda is a long-term program that can take time to affect people’s daily lives. It will succeed best over that long term if it is carefully blended with a redistribution agenda, with more predistribution and less redistribution over time. The Biden administration did not have the time or the capacity to complete the agenda. Khan was aggressive in challenging Big Tech power, but she was not able to see many cases to their conclusion. The administration attempted to support labor power, but fell short of adequately bolstering union membership or enforcing labor protections in critical parts of the infrastructure bills (Glickman and Dutta 2025). It tried to address junk fees and drug prices, but it did not fully confront the root causes of cost-push inflation (Nikiforos and Grothe 2023).

President Donald Trump’s mutant neoliberalism contrasts sharply with Biden’s incomplete predistribution. The Trump agenda constitutes backward predistribution and upward redistribution in that it deploys the rhetoric of anti-elitism while shifting wealth and power further toward those with wealth and power. The second Trump administration has destroyed state capacity by indiscriminately firing federal workers and slashing funding for government agencies (Acemoglu et al. 2025). It has cut investment in public goods, including education, infrastructure, and industrial policy. It has assaulted the welfare state with cuts to Medicare and Social Security. Just as Reagan evoked images of “welfare queens” to justify cuts to critical government programs, Trump has justified his cuts by scapegoating undocumented immigrants, “wokeness,” and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) programs. All the while, the administration has promised a massive tax reduction for the wealthy. It has deployed government powers to enrich the president and his family. It has targeted material rewards to friends, like Elon Musk (Hopkins and Lazonick 2024), and punishments to the president’s perceived enemies, including the media, universities, and law firms.

Markets and Power

The public investment policy bucket—including education, health care, and basic infrastructure—is essential to the predistribution policy agenda because it has the greatest potential to foster substantive equality of opportunity. This means going far beyond formal equality of opportunity under the law to strive to eliminate social, political, and institutional inequities. That includes equal access to education, housing, finance, and employment (Stiglitz 2016). This policy brief, however, focuses on the market governance policy bucket that sets the balance of power in the economy (Wong et al. 2023).

Market liberals believe that markets develop spontaneously and government “intervention” distorts market outcomes. Even the most ardent defenders of free markets would concede that markets require rules, like those protecting private property (Hayek 1944; Friedman 1962). Yet they underestimate the scale and scope of regulation necessary to make modern markets work. There is no “free market” in the literal sense: Markets are always governed. And governments have the unique ability to create and enforce laws and regulations over a given territory. We refer to this role as “marketcraft” because it constitutes a core function of government roughly comparable to statecraft (Vogel 2018).

Marketcraft addresses inequality at its root by acknowledging that all real-world markets are characterized by asymmetries of power and adjusting the rules to balance that power.

In this view, market governance is inevitable—but it is not neutral. That is, any regulation or practice or norm will favor some market participants over others, even if that was not the primary intent. Many standard economic models begin with the assumption of perfect markets, where price and quantity reach a natural equilibrium and government action requires justification based on an identifiable market failure. But this single point of natural equilibrium does not exist in the real world. If we imagine a spectrum of market governance options from those most favorable to incumbents to those most advantageous to challengers (as in Table 1), we cannot identify a specific point along that spectrum that represents the free-market or neutral position. That in turn suggests that it may be possible to alter that balance of power to promote public welfare without impeding competition or otherwise distorting markets (Vogel 2023). Marketcraft addresses inequality at its root by acknowledging that all real-world markets are characterized by asymmetries of power and adjusting the rules to balance that power.

Thomas Piketty (2014) identified a long-term trend for inequality to increase over time unless moderated or reversed by some major intervention, such as war or drastic tax or land reform. He presented this as a pattern of history, but he did not specify the mechanism driving the reinforcing cycle of wealth and power. The predistribution frame provides a way to understand that underlying mechanism.

Think of it this way. Firms seek to stay in business and to generate profits, and they can do so via two basic strategies: (1) create value (raise productivity) and/or (2) extract value (secure rents). Incumbent firms may prefer the latter because they may be vulnerable to challengers that might develop a product or a technique that renders their competitive advantage obsolete (Fligstein 2001). They may seek to insulate themselves from this threat rather than to rely on their ability to outrun the competition. To put this differently, firms can focus on building a better widget or manipulating market governance to maximize stability and profits with the widget they already have. In practice, of course, firms do both. But they can gain security by ensuring that they will survive even if they cannot always produce the best widget at the best price. And they are best able to maximize profits if they can supplement any price or quality advantage they might have with the exercise of market power to deter, impede, or absorb competitors. And as firms pursue strategies to secure rents, they seek to change laws and regulations (market governance) to enable them to do so. And this dynamic increases inequality over time, all else being equal (Vogel 2021).

The Inequality Snowball

- Firms seek both stability and profits.

- Firms can pursue these goals by raising productivity and/or by extracting rents.

- Firms deploy political strategies, such as lobbying, and business strategies, such as collaboration and collusion, to extract rents.

- To the extent that firms succeed in these strategies, inequality increases because dominant firms, their owners, and their executives garner rents at the expense of other firms and stakeholders, such as workers and customers.

- Political and market power reinforce each other to produce a snowball effect.

- This pattern continues unless disrupted by war, land reform, or major tax, social policy, or regulatory reforms.

The predistribution agenda offers a way to reverse this snowball effect.

The Case for Predistribution

We argue that priority ought to be given to predistribution over redistribution. Given the intertwined nature of the two types of policies, this means combining them in specific ways rather than simply favoring the former over the latter.

We give priority to predistribution as an overarching goal because it seeks to address the causes of inequality whereas redistribution focuses more on the symptoms. Predistribution policies address underlying causes, such as the unequal distribution of factor endowments and the imbalance of market and political power, so they have longer-term effects and are less vulnerable to short-term reversals.

The predistribution agenda does not accept labor exploitation and value extraction and then compensate for it, but rather strives to give workers fair wages and consumers fair value in the first place. Instead of allowing the market to underpay workers and then compensating them after the fact, the government should structure markets to pay them fairly in the first place. Instead of allowing producers to overcharge consumers and then compensating those consumers (who are also taxpayers and citizens), the government should set the market rules so that consumers pay fair prices in the first place.

Predistribution is respectful of human dignity because it favors fair wages and fair value. Redistribution can impose an expressive harm by giving one side an unjustified sense of desert and the other an unjustified sense of humiliation. Redistribution can reinforce a status hierarchy, with the combination of paternalism and dependency associated with the transfer of resources. In contrast, predistribution gives people self-respect and economic agency. Exercising capabilities is more fulfilling than receiving compensation. As Daniel Chandler (2023) puts it: “People want to be in charge of their own lives, to engage in meaningful work, and to develop relationships—at work and elsewhere—which support a sense of dignity and self-respect.” Reducing the dependency inherent in a system of redistribution can contribute to more solidarity among the populace and a greater sense of citizenship. This suggests that a predistribution strategy should include macroeconomic policies to promote full employment and labor market policies to foster stable employment.

Predistribution policy measures also enhance democracy by balancing power in the economy (Bagg 2023; Jackson 2023). In the real world, predistribution and redistribution policies are not introduced into a society born equal, but rather enacted in a society already riddled with political, social, and economic inequalities. Market governance reforms, such as corporate governance or labor reforms, can enhance democracy in the workplace (Nwanevu 2025). In this sense, predistribution remedies go beyond compensating individuals for bad luck and combat workplace oppression directly (Anderson 2017).

In addition, predistribution policies may be more durable because they favor expanding opportunities rather than taking from some and giving to others. In contrast, redistributive policies may be more vulnerable to backlash. The academic literature on “deservingness” highlights the complex sentiments associated with government aid, especially among its recipients (Whelan 2022). Studies find that race, class, and ethnicity strongly affect opinions on who deserves government support (Heuer and Zimmermann 2020; Reeskens and van der Meer 2019). This does not mean that redistribution programs should be left to the whims of those who believe others are less deserving, but that we must recognize that these views make redistributive policies more vulnerable to backlash at times of social change (Gee, Migueis, and Parsa 2017). While redistributive measures such as wealth taxes and income transfers are needed to eliminate inequities, policy design that takes into account sentiment on deservingness can help ensure that these policies survive politically (Ellis and Faricy 2020).

We should acknowledge, however, that some redistribution policies can be durable and some predistribution policies are likely to encounter opposition from powerful interest groups. In particular, predistribution policies that aim to shift power away from the wealthy and powerful are likely to meet considerable resistance, as we are seeing today.

Predistribution as Marketcraft

The inequality snowball, and its extreme variant in the United States of the past 40 years, suggests that political institutions are critical to reform. That means that defending democratic institutions may be essential to enacting a marketcraft reform agenda at all, and political reforms such as limiting corporate campaign contributions or expanding voting rights may be a prerequisite for bolder reforms. Likewise, it suggests that elements of the agenda that constrain both the political and the market power of dominant firms—such as antitrust and labor regulation—should be prioritized, because they could jointly constrain the inequality snowball (Vogel 2021). Focusing on these two critical policy areas, we outline both short- and long-term policy prescriptions that would rebalance power and build a more democratic economy.

Antitrust

The past 50 years of relatively lax antitrust enforcement have led to a significant increase in market concentration. This has fueled the rise of superstar firms, which have garnered much higher returns than other companies, and enabled labor market monopsonies, whereby firms can pay lower wages (Boushey 2019). Labor market monopsony in the narrow sense refers to a situation in which a single employer dominates a market, such as in a given geographical area, but it can also be applied more broadly to markets with multiple employers when the employers have a substantial advantage in power relative to workers.Thomas Philippon (2019) argues that the decrease in competition in the US economy since the 1990s has led to higher price markups, higher after-tax profits, lower investment, lower productivity, a lower labor share of income, and higher inequality. He stresses, moreover, that the stakes are huge. He estimates that if the 2018 economy were as competitive as it was 20 years earlier, GDP would be 5 percent higher, meaning $1.5 trillion more income for American workers. Hence, strengthening antitrust would deliver higher economic benefits than almost any other proposed policy reform.

A more robust antitrust policy would embrace a “neo-Brandeisian” approach that seeks to reduce inequality, strengthen labor power, balance power in the economy, and promote democracy (Vogel 2023). The government would move beyond the consumer welfare standard in evaluating antitrust policies and enforcement to recognize antitrust’s role in combating concentrations of power more broadly (Glick, Lozada, and Bush 2024; Steinbaum and Stucke 2018). Doing so would not only foster lower prices and higher wages but also align with how many Americans feel about the current concentration of market and political power. In conflicts between organized labor and big business, Americans are more likely to support labor now than any other time on record. From the 1960s to 2012, opinions for labor and business tended to rise and fall together. Data from 2024, however, show that positive sentiment toward labor unions have continued to rise while sentiment for big business fell to its lowest point on record (Sojourner and Reich 2025). Despite this trend, significant shifts in policy have yet to manifest.

In practical terms, a neo-Brandeisian approach would entail aggressively combating the power of Big Tech firms through court cases, stricter merger enforcement, and more rigorous scrutiny of anticompetitive practices. In addition, the government should shift the burden of proof from plaintiffs to defendants. It should aggressively challenge market power in court, even when the chances of victory are unsure. And it should allocate more resources to antitrust enforcement overall. The Biden administration made substantial progress in these areas, but the government could go much further.

State governments can also play critical roles in strengthening antitrust enforcement where the federal government and courts lag. In 1963, North Dakota passed a law that required pharmacies to be owned by licensed pharmacists. This law effectively banned large chains from operating as pharmacies, breaking up the vertical integration of the pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) that mediate between health insurers and pharmacies. Studies find the market for PBMs is highly concentrated, with just three companies accounting for nearly 80 percent of all prescriptions in the United States as of 2023 (Martin 2025). PBMs are also often vertically integrated with large chain pharmacies, allowing them to leverage their power into retail markets, driving out independent pharmacies. Numerous studies have shown this combination of market concentration and vertical integration has put upward pressure on drug prices, and has contributed to detrimental health outcomes, including the opioid epidemic (US FTC Office of Policy Planning 2024). Meanwhile, North Dakota’s pharmacy ownership law has increased access to critical pharmaceutical care, lowered costs, and improved health outcomes (Mitchell and LaVecchia 2014; Leslie 2024; Qato, Chen, and Van Nuys 2024). In effect, this law has “filled the vacuum left by the failure of antitrust policy to promote and maintain an open and competitive market” (Mitchell 2016). By prohibiting PBMs from vertically integrating with pharmacy retailers, North Dakota has effectively shifted the balance of power away from incumbents toward challengers, with beneficial results.

In the short term, antitrust reformers will have the most success with measures that are both politically salient and popular, such as eliminating junk fees, attacking price gouging, and combating practices that keep drug prices high. They are also likely to garner public support for selective measures to take on the power of the Big Tech platform firms. Over the longer term, antitrust policy will be critical to creating a potential virtuous circle to reverse the concentration of market and political power, making markets work better for consumers and workers and fostering democracy in both markets and politics.

Labor Market Governance

A labor market reform agenda should include measures to make it easier for unions to organize and harder for companies to block them, institutions to support organization in the gig and other service sectors, rules to strengthen the representation of workers in “fissured” workplaces such as franchises, mechanisms for bargaining at the sectoral level, and a ban on noncompete clauses. Policies that guarantee all workers, regardless of political status, dignity, respect, and a fair wage ought to be prioritized over band-aid policies that exploit differences and break apart working-class coalitions. Furthermore, the government should strengthen enforcement of these laws and empower institutions such as the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to disincentivize and punish wage theft with fines. The government should comprehensively address labor market discrimination and segmentation that drives down wages for all. It should strengthen the voice of workers in corporate governance. And to rebalance labor power effectively, it needs to move beyond labor policies per se to design macroeconomic policies that strive for full employment and policies for health care, housing, and transport that address the affordability crisis.

The neoclassical approach to labor economics begins with the presumption of perfectly competitive markets. Employers are wage-takers, only able to pay workers the rate that the market decides, and workers are paid what they “deserve”—that is, according to their marginal productivity (Mankiw 2013). In reality, however, labor markets are plagued by monopsony, an imbalance of power in favor of employers over workers (Vogel 2025). Recent economic literature demonstrates that workers are not able to switch jobs as easily as the theory suggests, revealing widespread evidence of monopsony in labor markets (Caldwell and Naidu 2020).

The imbalance of power between employers and workers is exacerbated by social stratification, whereby employers wield greater power over Black and brown employees, immigrants, and less educated workers. The result is increasing inequality and suppressed and stolen wages, largely along racial, ethnic, and social lines. Disparate salary outcomes across these groups are primarily the product of rules and norms, and not individual choices or group culture (Mason 2023). These divisions and our current market rules, reinforced by practices and norms, break apart labor coalitions and render them more vulnerable to dominant interests.

Theoretically, the quit elasticity (how likely a worker is to quit a job in response to a wage change) of a perfectly competitive labor market should be nearly 100 percent. That is, even a small wage decrease should make the probability of an average worker quitting a near certainty. However, research suggests that in reality a 10 percent decrease in firm wages only increases the probability that a worker will quit by 20–30 percent. Importantly, this number varies based on demographics—the quit elasticity is 0.16 for men compared to 0.09 for women, meaning men are twice as likely to quit given the same size wage decrease. The quit elasticity is 0.12 for white workers compared to 0.07 for Black workers. The research finds that historically disadvantaged groups are less responsive to changes in wages, implying firms have more power to suppress their pay and exploit their labor (Naidu and Carr 2022). This is likely due to structural barriers such as persistent underemployment and labor market discrimination that make quitting far costlier for marginalized groups, especially Black Americans (Mason 2023).

Divisions among workers allow employers, especially those with disproportionate market power, to leverage one group against the other, and drive everyone’s wages, benefits, and working conditions further down. In this way, the fates of working Americans are tied, independent of ethnicity, race, gender, or education. As such, the most effective way to rebalance power toward employees is to raise the standard of the most vulnerable, while ensuring the protection of all workers.

Some employers abuse immigration enforcement mechanisms to uphold dangerous workplace conditions, enable wage theft, and quash collective bargaining efforts. Evidence suggests that the exploitation of visa holders has kept workers in tech sectors from calling attention to detrimental workplace conditions, advocating for better pay, and even calling out unjust company practices. Indeed, states with the strictest immigration enforcement have also been sites of the strongest crackdowns on unions and workers writ large (Macher 2025).

In recent years, the federal government has increasingly relied on I-9 inspections to enforce immigration standards in the workplace, rooting out unlawful employment based on legal status. In practice, workplace raids rarely punish lawbreaking employers and instead enable firms to punish workers and degrade standards, substantially weakening labor coalitions (Smith, Avendaño, and Martínez Ortega 2009; Costa 2025). The employers often avoid serious charges because prosecutors must prove that the employers “knowingly” employed someone without proper documentation. Meanwhile, workers caught in workplace raids are given the option to sign a voluntary departure, are detained and released on bond, or held in custody, all of which undermine efforts to hold employers accountable for pay and hazard violations. Furthermore, because I-9 workplace raids do not enforce workplace pay or hazard violations, targeted employers are not required to pay the owed back wages (Costa 2025). The prioritization of enforcing immigration law, which puts the burden on workers, over labor law, which puts the burden on employers, enables workplaces to get away with serious labor violations. Indeed, an Economic Policy Institute analysis found that the federal government spends 14 times more on enforcing immigration laws than it does on enforcing labor standards (Costa 2022). This asymmetry is exemplified in instances where employers threaten to call Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on themselves in times of workplace disputes or union organizing, effectively using raids as a tool to keep workers from exercising power over working conditions and pay (Khouri 2018; Costa 2025). To counter this, the government must shift the paradigm from immigration enforcement to labor standard enforcement, shifting the legal burden from employees to employers. In practice, this means protecting bargaining and cracking down on unsafe and illegal working conditions, independent of a worker’s legal status.

In the long term, a predistributive labor policy must address the affordability crisis that restricts worker mobility and drives inequality. Policy prescriptions such as a full employment mandate and universal health care would provide the flexibility and security necessary for workers to search for better opportunities (Dube 2025; Pancotti and Jacquez 2025; El-Sayed 2025; Stein and Regmi 2024). Prioritizing full employment would increase bargaining power and reduce persistent inequalities in the labor market. Similarly, a universal health-care system would reduce costs and shift away from the reliance on employer-sponsored insurance schemes that perpetuates inequality (Hager et al. 2024).

A long-term predistribution strategy would also seek to rebalance power toward employees by building economic democracy. This means policies that increase worker say in how firms are run, either informally through unions or more structurally through labor representation on corporate boards. Breaking apart concentration in the economic realm means increasing employee voice in fundamental decision-making—implementing democracy in the workplace (Ferreras, Battilana, and Méda 2022).

The Varieties of Marketcraft: Corporate Governance, Finance, and Intellectual Property

Other modes of market governance also shape the power balance between actors in the economy, similar to antitrust and labor regulation (Hughes and Spiegler 2023; Vogel 2023). In corporate finance, the United States has shifted since the 1970s toward a shareholder model of corporate governance in which corporations prioritize the goal of maximizing shareholder returns rather than serving the interests of a broader range of stakeholders, such as workers, customers, and the community. Corporations and institutional investors lobbied for the legal changes that propelled this shift, and they have taken advantage of these changes to boost share prices and executive compensation over wages and investment. This in turn has amplified economic inequality, especially at the top end of the income spectrum. It will not be easy to reverse this trend, but reformers should be able to mobilize support by focusing on the most egregious abuses and beginning with measures that are likely to be the most feasible, such as limits on share buybacks and restrictions on executives’ ability to cash in stock options (Palladino 2025). Over the longer term, however, policymakers will only be able to counterbalance the power of shareholders and managers by requiring labor and public-interest representation on corporate boards to enhance the democratic governance of corporations.

Predistribution policies in finance would restore commonsense financial guardrails that disincentivize speculation and rent-seeking. Reforms since the 1970s—including the liberalization of interest rates, stock commissions, and interstate banking, and the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act—facilitated financial innovation, propelled industry consolidation, and set the stage for the global financial crisis of 2008. They also contributed to a doubling of the size of the financial sector from about 4 percent of GDP in 1980 to 8 percent in 2008 without providing greater value to financial consumers. Financial reforms contributed to growing economic inequality, especially the enormous rise in the fortunes of the top 1 percent and the very top 0.1 percent of the most wealthy. Thomas Philippon and Ariell Reshef (2012) find that finance sector workers earned comparable wages to workers in other sectors until 1990, but they gained a 50 percent premium and top finance executives a 250 percent premium by 2006. Reformers should first propose those measures most likely to garner public support, such as cracking down on junk fees, curtailing predatory interest rates, and restoring consumer financial protection. Over the longer term, however, the United States will have to move toward comprehensive financial reform to ensure that the financial sector creates more value and extracts less. Key pillars of this strategy should include establishing a fiduciary duty for investment managers and imposing a financial transactions tax. This includes incorporating strong redistributive measures to balance power, such as taxing excess corporate profits (Lusiani and Regmi 2025).

With regard to intellectual property (IP) protection, the US regime has contributed to growing inequality by enabling firms that enjoy the benefits of IP protection to increase their profits and salaries for managers and core workers at the expense of other firms, workers, and consumers (Vogel 2021). The IP regime accelerates the inequality snowball because those with wealth and power have the greatest access to protection. The IP regime in the pharmaceutical sector has contributed to inequality by encouraging innovations valued by the wealthy over those needed by the poor and fueling high drug prices for consumers (Boushey 2019). Practical short-term reforms could include reducing patent protection for pharmaceuticals as one element in a larger initiative to bring down pharmaceutical prices. Over the longer term, the United States should substantially reduce IP protection to facilitate collaboration and innovation and to reduce costs for IP users. The extension of patents to software and business methods plus the easing of standards for IP protection have increased the costs and reduced the benefits of this protection. Moreover, the digital revolution has enabled collaborative models of innovation, such as open-source software development, that can be hampered by strong IP protection (Benkler 2017).

IP protection has also contributed to the restructuring of the US economy in ways that exacerbate inequality. High-profit firms with IP share their rents with a relatively small core of workers, while many firms in more competitive industries squeeze their workers with lower wages and less favorable work conditions. The US firms with the highest level of profits are concentrated in those sectors characterized by a high reliance on IP, especially pharmaceuticals and high technology (Schwartz 2016). Sectors that rely heavily on IP tend to exhibit high returns to scale, with high fixed costs and low marginal costs, and that can translate into a winner-take-all dynamic with high profits for the dominant firms and outsized incomes for superstar individuals (such as athletes or entertainers).

Alternative Policy Paradigms: “Abundance” and “Productivism”

We review here the case for the predistribution agenda as a guiding vision by comparing and contrasting it to two alternative visions that have been prominent in the public debate: the abundance agenda and productivism.

Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson (2025) have proposed an “abundance agenda” whereby the government would embrace pro-growth economic policies and focus on removing obstacles to the efficient delivery of government services. They center the book on a simple idea: “To have the future we want, we need to build and invent more of what we need” (4). They do not position the abundance agenda as a full-fledged policy paradigm but rather as a possible pathway to a new political order. They focus on the supply side of the economy in the sense of the supply of key public goods, such as housing, energy, and transportation. They contend that well-meaning liberals over the decades have imposed too many regulations, administrative reviews, and other chokeholds that impede building and growth. Their agenda overlaps with the predistribution agenda in that it advocates for greater public investment and seeks policy remedies that transcend redistribution.

Klein and Thompson share this policy brief’s interest in market regulation, yet they come to a different conclusion. They generally advocate for less regulation (although they do bring nuance to this stance), whereas we favor reforming regulation to shift power from the wealthy and the powerful to workers and consumers—that is, to everyone else. We endorse their call for fewer senseless regulations, lower prices, and better lives, but we stress that regulations can enhance welfare as well as undermine it. For one thing, regulations powerfully shape the distribution of abundance. Effective regulatory reform is more like brain surgery than dynamite blasting. Sandeep Vaheesan (2025) persuasively argues that Klein and Thompson overestimate the role of regulation in obstructing the supply of housing or clean energy. More significantly, they gloss over the issues of power and inequality at the heart of the predistribution agenda, and assume that abundance will benefit everyone (Weber 2025; Jackson 2025). Yet the United States since 1980 has proven the opposite. We have achieved strong economic growth, and yet that growth has hardly benefited most Americans (Figure 1).

Dani Rodrik (2023) and others (Ferry 2024) have proposed “productivism” as an animating vision for economic policy. It seeks to promote productive economic opportunities throughout all regions of the economy and all segments of the labor force. It puts less faith in markets and large corporations and favors production and investment over finance, and revitalizing local communities over globalization. It focuses less on redistribution, social transfers, and macroeconomic management and more on supply-side measures to create good jobs for everyone.

Productivism overlaps considerably with the predistribution agenda proposed here in that it seeks to address economic inequality by enhancing the capabilities of individuals, firms, and states and expanding life chances more than by redistributing funds. It focuses especially on supply-side industrial policies designed to generate more good jobs broadly across geographical regions and industrial sectors. The productivism agenda complements the predistribution agenda outlined in this brief in that it fleshes out the public investment side (from Table 2), especially with regard to industrial policy.

Yet productivism largely overlooks the marketcraft agenda, which is critical to break from neoliberalism and plutocratic populism. To promote productivity, the United States needs to move beyond industrial policy in the narrower sense of government investment, finance, and coordination. It needs to strengthen antitrust enforcement to promote innovation, reduce intellectual property protection to foster more collaborative models of innovation, and enhance labor’s voice in management to nurture labor-management cooperation and enhance productivity (Vogel 2021). More fundamentally, the marketcraft agenda is critical to balance power in the market and in politics. This will have the direct benefit of making the economic system more fair and the political system more democratic, and the indirect benefit of fostering better policy and more healthy politics over the long term.

Conclusion

We believe that predistribution would address two of the biggest challenges confronting the United States today: economic inequality and a faltering democracy. And overcoming those is a prerequisite to addressing the substantive challenges of our time such as climate change and financial instability. The predistribution agenda offers the best alternative vision to both the neoliberalism of Reagan and its mutant variety in the plutocratic populism of today (Callison and Manfredi 2019; Hacker and Pierson 2020).

As described in the antitrust, labor, and the varieties of marketcraft sections of this brief, only a predistribution agenda could reverse the trend toward greater concentration of power and wealth. We readily concede that this is not the most likely moment for the government to turn toward this agenda. Yet we need a vision for where we want to go before we can craft political strategies to move in that direction. And the extreme concentration of wealth and power in the United States today could very well inspire a movement to counter it.

The shortcomings of past predistributive efforts do not imply that we should tread softly on this terrain—quite the opposite. This is the time to develop bold visions for a better future. Americans not only want but deserve economic security, including good jobs and reasonable prices. They neither want nor deserve an oligarchy, with highly concentrated economic and political power. The predistribution solution can address those things. Over the long term, policymakers must develop a comprehensive predistribution agenda to shift the balance of power in the economy and offer Americans dignity and the opportunity to thrive.

Footnotes

- Martin O’Neill (2020) finds that the term “predistribution” was used earlier by James Robertson (2005). ↩︎

- Over the longer term, however, Reagan could not halt gradual increases in Medicaid, Medicare, and Social Security spending as he compromised with Congress and the programs expanded to meet the demands of an aging population (Pierson 2012). ↩︎

- Only 25 percent of Americans say they have a good chance of improving their standard of living – the lowest share on record since the survey began in 1987. And 46 percent respond that the American Dream (that hard work leads to upward mobility) no longer holds while 23 percent state that it never held, according to a Wall Street Journal/NORC Poll (2025). ↩︎

- Japan provides an illuminating contrasting case with a strong record on predistribution, including high public investment and quality public education in the postwar era plus market governance that favored benefits for a wide range of stakeholders rather than narrower rents for shareholders and top executives. In particular, Japan’s government support for farmers and small retailers—while not efficient according to a standard economic assessment—meant that family farmers and shop owners could achieve a stable middle-class standard of living (Vogel 2022). ↩︎

References

Acemoglu, Daron, Peter Diamond, Oliver Hart, Simon Johnson, Paul Krugman, and Joseph Stiglitz. 2025. “The Upside-down Priorities of the House Budget: Adding Significantly to Debt While Reducing Incomes for the Bottom 40%.” Economic Policy Institute, June 2. https://epi.org/publication/the-upside-down-priorities-of-the-house-budget.

Alden, Edward. 2016. Failure to Adjust: How Americans Got Left Behind in the Global Economy. Rowman & Littlefield. https://cfr.org/book/failure-adjust.

Anderson, Elizabeth. 2017. Private Government: How Employers Rule Our Lives. Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691176512/private-government.

Aratani, Lauren. 2024. “Majority of Americans Wrongly Believe US Is in Recession – and Most Blame Biden.” US News. The Guardian, May 22, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/article/2024/may/22/poll-economy-recession-biden.

Bagg, Samuel. 2023. “Whose Coordination? Which Democracy? On Antitrust as a Democratic Demand.” SSRN Scholarly Paper 4503662. Social Science Research Network, July 4. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4503662.

Benkler, Yochai. 2017. “Law, Innovation, and Collaboration in Networked Economy and Society.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 13: 231-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113340.

Blanchard, Olivier, and Dani Rodrik. 2021. Combating Inequality: Rethinking Government’s Role. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/13469.001.0001.

Blanchet, Thomas, Lucas Chancel, and Amory Gethin. 2022. “Why Is Europe More Equal than the United States?” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 14 (4): 480–518. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20200703.

Boushey, Heather. 2019. Unbound: How Inequality Constricts Our Economy and What We Can Do about It. Harvard University Press. https://hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674251380.

Brown, Wendy. 2006. “American Nightmare: Neoliberalism, Neoconservatism, and De-Democratization.” Political Theory 34 (6): 690–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591706293016.

Caldwell, Sydnee, and Suresh Naidu. 2020. Wage and Employment Implications of U.S. Labor Market Monopsony and Possible Policy Solutions. Washington Center for Equitable Growth. https://equitablegrowth.org/wage-and-employment-implications-of-u-s-labor-market-monopsony-and-possible-policy-solutions.

Callison, William, and Zachary Manfredi, eds. 2019. Mutant Neoliberalism: Market Rule and Political Rupture. Fordham University Press. https://doi.org/10.5422/fordham/9780823285716.001.0001.

Chandler, Daniel. 2023. Free and Equal: A Manifesto for a Just Society. Knopf. https://penguinrandomhouse.com/books/743628/free-and-equal-by-daniel-chandler.

Chetty, Raj, David Grusky, Maximilian Hell, Nathaniel Hendren, Robert Manduca, and Jimmy Narang. 2017. “The Fading American Dream: Trends in Absolute Income Mobility since 1940.” Science 356 (6336): 398–406. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aal4617.

Costa, Daniel. 2022. Threatening Migrants and Shortchanging Workers: Immigration Is the Government’s Top Federal Law Enforcement Priority, While Labor Standards Enforcement Agencies Are Starved for Funding and Too Understaffed to Adequately Protect Workers. Economic Policy Institute, December 15. https://epi.org/publication/immigration-labor-standards-enforcement.

_____ 2025. “FAQ: Immigration Enforcement and the Workplace.” Economic Policy Institute, March 15. https://epi.org/publication/immigration-enforcement-and-the-workplace.

Daly, Lew, and Sylvia Chi. 2022. Clean Energy Neoliberalism: Climate, Tax Credits, and Racial Justice. Roosevelt Institute. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/clean-energy-neoliberalism.

Dube, Arindrajit. 2025. “Full Employment: A Policy Choice Worth Pursuing.” Roosevelt Institute, April 29. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/blog/full-employment.

Ellis, Christopher, and Christopher Faricy. 2020. “Race, ‘Deservingness,’ and Social Spending Attitudes: The Role of Policy Delivery Mechanism.” Political Behavior 42 (3): 819–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-018-09521-w.

El-Sayed, Abdul. 2025. “The US Health-Care System Is One of Tiered Citizenship.” Roosevelt Institute, April 29. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/blog/us-health-care-tiered-citizenship.

Ferreras, Isabelle, Julie Battilana, and Dominique Méda. 2022. Democratize Work: The Case for Reorganizing the Economy. Translated by Miranda Richmond Mouillot. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/D/bo154077035.html.

Ferry, Jeff. 2024. “Economic View: Productivism Is the Key to National Prosperity.” Coalition for a Prosperous America, April 15, 2024. https://prosperousamerica.org/economic-view-productivism-is-the-key-to-national-prosperity/.

Fligstein, Neil. The Architecture of Markets: An Economic Sociology of Twenty-First Century Capitalist Societies. 2. print., and 1. paperback print. Princeton Univ. Press, 2001.

Floyd, Ife, LaDonna Pavetti, Laura Meyer, et al. 2021. TANF Policies Reflect Racist Legacy of Cash Assistance. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://cbpp.org/research/income-security/tanf-policies-reflect-racist-legacy-of-cash-assistance.

Friedman, Milton. 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. Edited by Binyamin Appelbaum. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/C/bo68666099.html.

Frost, Riordan. 2025. “Five Ways Residential Mobility Has Changed in the Pandemic Era.” Join Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University, March 26. https://jchs.harvard.edu/blog/five-ways-residential-mobility-has-changed-pandemic-era.

Gee, Laura K., Marco Migueis, and Sahar Parsa. 2017. “Redistributive Choices and Increasing Income Inequality: Experimental Evidence for Income as a Signal of Deservingness.” Experimental Economics 20 (4): 894–923. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-017-9516-5.

Glick, Mark, Gabriel A. Lozada, and Darren Bush. 2024. “Antitrust’s Normative Economic Theory Needs a Reboot.” Institute for New Economic Thinking, December 9. https://ineteconomics.org/research/research-papers/antitrusts-normative-economic-theory-needs-a-reboot.

Glickman, Susannah, and Madhumita Dutta. 2025. “Chips on the Table.” The American Prospect, January 30. https://prospect.org/economy/2025-01-30-chips-on-the-table.

Hacker, Jacob S. 2005. “Policy Drift: The Hidden Politics of US Welfare State Retrenchment.” In Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies, edited by Streeck Wolfgang and Thelen Kathleen. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199280452.003.0002.

_____ 2011. “The Institutional Foundations of Middle-Class Democracy.” Policy Network 6 (5): 33–37. https://assets.website-files.com/64a8727f61fabfaa63b7b770/64aab85cf813ccbee57ce07f_hacker_pn.pdf.

Hacker, Jacob S., and Paul Pierson. 2020. Let Them Eat Tweets: How the Right Rules in an Age of Extreme Inequality. Liveright. https://wwnorton.com/books/9781631496844.

Hager, Kurt, Ezekiel Emanuel, and Dariush Mozaffarian. 2024. “Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Premium Cost Growth and Its Association With Earnings Inequality Among US Families.” JAMA Network Open 7, no. 1 (2024): e2351644. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.51644.

Haney López, Ian. 2013. Dog Whistle Politics: Strategic Racism, Fake Populism, and the Dividing of America. Oxford University Press.

Hayek, F. A. 1944. The Road to Serfdom: Text and Documents. Edited by Bruce Caldwell. The Collected Works of F. A. Hayek. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/R/bo4138549.html.

Heuer, Jan-Ocko, and Katharina Zimmermann. 2020. “Unravelling Deservingness: Which Criteria Do People Use to Judge the Relative Deservingness of Welfare Target Groups? A Vignette-Based Focus Group Study.” Journal of European Social Policy 30 (4): 389–403. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928720905285.

Hopkins, Matt, and William Lazonick. 2024. “Musk and Tesla: Corporate Compensation, Financialization, and the Problem of Strategic Control.” Institute for New Economic Thinking, September 13. https://ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/musk-and-tesla-corporate-compensation-financialization-and-problem-of-strategic-control.

Hovenkamp, Herbert. 2005. “IP and Antitrust Policy: A Brief Historical Overview.” All Faculty Scholarship, December 9. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/faculty_scholarship/1916.

Hughes, Chris, and Peter Spiegler. 2023. “Marketcrafting: A 21st-Century Industrial Policy,” Roosevelt Institute, May 31. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/marketcrafting-a-21st-century-industrial-policy.

Jackson, Kate. 2023. “Antitrust and Equal Liberty.” Politics & Society 51 (3): 337–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323292231183825.

Jackson, Trevor. 2025. “How to Blow Up a Planet.” The New York Review of Books, September 25. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2025/09/25/how-to-blow-up-a-planet-abundance-klein-thompson/.

Khouri, Andrew. 2018. “More Workers Say Their Bosses Are Threatening to Have Them Deported.” Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/business/la-fi-immigration-retaliation-20180102-story.html.

Klein, Ezra, and Derek Thompson. 2025. Abundance. Avid Reader Press / Simon & Schuster.

Kuziemko, Ilyana, Nicolas Longuet-Marx, and Suresh Naidu. 2023. “‘Compensate the Losers?’ Economic Policy and Partisan Realignment in the US.” Working Paper 31794. National Bureau of Economic Research, October. https://doi.org/10.3386/w31794.

Leslie, Christopher R. 2024. “Pharmacy Deserts and Antitrust Law.” Boston University Law Review 104 (6): 1593. https://bu.edu/bulawreview/files/2024/12/LESLIE.pdf.

Lichtenstein, Nelson. 2018. “A Fabulous Failure: Clinton’s 1990s and the Origins of Our Times.” The American Prospect, January 29. https://prospect.org/api/content/9f0bc823-3685-59c1-8904-e177727974bf.

Lusiani, Niko, and Ira Regmi. 2025. Taxing Excessive Profits: Designing a pro-Competition Corporate Tax System. Roosevelt Institute. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/taxing-excessive-profits.

Macher, Michael. 2025. “Wages of Citizenship.” Phenomenal World, April 10. https://phenomenalworld.org/analysis/wages-of-citizenship.

Mankiw, N. Gregory. 2013. “Defending the One Percent.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 27 (3): 21–34. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.27.3.21.

Martin, Kristi. 2025. “What Pharmacy Benefit Managers Do, and How They Contribute to Drug Spending.” Commonwealth Fund, March 17. https://doi.org/10.26099/fsgq-y980.

Mason, Patrick L. 2023. The Economics of Structural Racism: Stratification Economics and US Labor Markets. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009290784.

Mitchell, Stacy. 2016. “The View from the Shop—Antitrust and the Decline of America’s Independent Businesses.” Antitrust Bulletin 61 (4): 498–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003603X16676139.

Mitchell, Stacy, and Olivia LaVecchia. 2014. North Dakota’s Pharmacy Ownership Law Leads to Better Pharmacy Care. Institute for Local Self-Reliance. https://ilsr.org/articles/report-pharmacy-ownership-law.

Naidu, Suresh, and Michael Carr. 2022. If You Don’t like Your Job, Can You Always Quit?: Pervasive Monopsony Power and Freedom in the Labor Market. Economic Policy Institute. https://epi.org/unequalpower/publications/pervasive-monopsony-power-and-freedom-in-the-labor-market.

Nikiforos, Michalis, and Simon Grothe. 2023. “Markups, Profit Shares, and Cost-Push-Profit-Led Inflation.” Institute for New Economic Thinking, June 6. https://ineteconomics.org/perspectives/blog/markups-profit-shares-and-cost-push-profit-led-inflation.

Nwanevu, Osita. 2025. “By the Workers, for the Workers: Building Economic Democracy.” Roosevelt Institute, April 29. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/blog/by-the-workers-for-the-workers.

O’Neill, Martin. 2020. “Power, Predistribution, and Social Justice.” Philosophy 95 (1): 63–91. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0031819119000482.

Palladino, Lenore. 2025. “Reining in Corporate Power.” Roosevelt Institute, April 29. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/blog/reining-in-corporate-power.

Pancotti, Elizabeth, and Alex Jacquez. 2025. “Breathing Room for All: Tackling the Cost-of-Living Crisis with Progressive Policy Solutions.” Roosevelt Institute, April 29. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/blog/breathing-room-for-all.

Philippon, Thomas. 2019. The Great Reversal: How America Gave Up on Free Markets. Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv24w62m5.

Philippon, Thomas, and Ariell Reshef. 2012. “Wages and Human Capital in the U.S. Finance Industry: 1909–2006*.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 127 (4): 1551–609. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjs030.

Pierson, Paul. 2012. Dismantling the Welfare State?: Reagan, Thatcher and the Politics of Retrenchment. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511805288.

Piketty, Thomas. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press. https://hup.harvard.edu/books/9780674430006.

Posner, Richard. 1979. “The Chicago School of Antitrust Analysis.” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 127 (4): 925. https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/penn_law_review/vol127/iss4/15.

Qato, Dima M., Yugen Chen, and Karen Van Nuys. 2024. “Pharmacy Benefit Manager Market Concentration for Prescriptions Filled at US Retail Pharmacies.” JAMA 332 (15): 1298–99. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.17332.

Reeskens, Tim, and Tom van der Meer. 2019. “The Inevitable Deservingness Gap: A Study into the Insurmountable Immigrant Penalty in Perceived Welfare Deservingness.” Journal of European Social Policy 29 (2): 166–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718768335.

Robertson, James. 2005. “The Future of Money: If We Want a Better Game of Economic Life We’ll Have to Change the Scoring System.” Soundings 2005 (31). https://journals.lwbooks.co.uk/soundings/vol-2005-issue-31/abstract-7061.

Rodgers, Daniel. 2018. “The Uses and Abuses of ‘Neoliberalism.’” Dissent Magazine, Winter 2018. https://dissentmagazine.org/article/uses-and-abuses-neoliberalism-debate/.

Rodrik, Dani. 2023. “On Productivism.” HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series, nos. RWP23-012 (March). https://hks.harvard.edu/publications/productivism.

Saez, Emmanuel, and Gabriel Zucman. 2019. “Progressive Wealth Taxation.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, no. 2 (Fall): 437–533. https://brookings.edu/articles/progressive-wealth-taxation.

Schwartz, Herman Mark. 2016. “Wealth and Secular Stagnation: The Role of Industrial Organization and Intellectual Property Rights.” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 2 (6): 226–49. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2016.2.6.11.

Smith, Rebecca, Ana Ana Avendaño, and Julie Martínez Ortega. 2009. Iced Out: How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers’ Rights. AFL-CIO, American Rights at Work Education Fund, and National Employment Law Project, October 1. https://hdl.handle.net/1813/88125.

Sojourner, Aaron, and Adam Reich. 2025. “Americans Favor Labor Unions over Big Business Now More than Ever.” Economic Policy Institute, May 20. https://epi.org/blog/americans-favor-labor-unions-over-big-business-now-more-than-ever.

Stein, David, and Ira Regmi. 2024. The Civil Rights Struggle for True Full Employment. Roosevelt Institute. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/publications/civil-rights-full-employment.